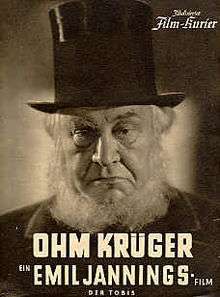

Ohm Krüger

| Ohm Krüger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Hans Steinhoff |

| Produced by | Emil Jannings |

| Written by |

Harald Bratt Kurt Heuser |

| Starring |

Emil Jannings - Paul Krüger Lucie Höflich - Sanna Krüger Werner Hinz - Jan Krüger Ernst Schröder - Adrian Krüger Elisabeth Flickenschildt - Frau Kock Ferdinand Marian - Cecil John Rhodes |

| Music by | Theo Mackeben |

| Cinematography | Fritz Arno Wagner |

| Edited by |

Martha Dübber Hans Heinrich |

Production company | |

Release dates |

4 April 1941 (Nazi Germany) 1 October 1941 (France) 15 March 1942 (Finland) |

Running time | 135 min. |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Budget | Over 5.5 million RM[1] |

Ohm Krüger (English: Uncle Krüger) is a 1941 German biographical film directed by Hans Steinhoff and starring Emil Jannings, Lucie Höflich and Werner Hinz. It was one of a series of propaganda films produced in Nazi Germany attacking the British. The film depicts the life of the South African politician Paul Kruger and his eventual defeat by the British during the Boer War.

It was the first film to be awarded the 'Film of the Nation' award. It was re-released in 1944.

Plot

The film opens with a dying Paul Krüger (Emil Jannings) speaking about his life to his nurse in a Geneva hotel. The rest of the film is told in flashback.

Cecil Rhodes (Ferdinand Marian) has a great desire to acquire land in the region of the Boers for its gold deposits. He sends Dr Jameson (Karl Haubenreißer) there to provoke border disturbances, and secures support from Joseph Chamberlain (Gustaf Gründgens). When Chamberlain seeks the support of Queen Victoria (Hedwig Wangel) and her son Edward, Prince of Wales (Alfred Bernau), she initially refuses but changes her mind when informed of the gold in the region. She invites Paul Krüger to London, and believes she is tricking him into signing a treaty.

Krüger, being suspicious of the British, has his own plans. Krüger signs the treaty which gives the British access to the gold; however, he imposes high taxes and establishes a monopoly over the sale of TNT which forces the British to buy explosives at high prices. Hence, ultimately, Krüger tricks the British by signing the treaty. This impresses some of the British as they find Krüger is their equal in matters of cunning, which is supposed to be the defining characteristic of the British. Having been outmaneuvered, Rhodes tries to buy Krüger's allegiance. Krüger and his wife Sanna (Lucie Höflich), however, are incorruptible. After being rejected, Rhodes shows Krüger a long list of members of the Boer council who work for the British. Krüger then becomes convinced that war is inevitable if the Boers are to keep their land. He declares war.

Initially, the Boers are on the ascendancy, leading Britain to appoint Lord Kitchener (Franz Schafheitlin) as Supreme Commander of the armed forces. Kitchener launches an attack on the civilian population, destroying their homes, using some as human shields and placing the women and children in concentration camps, in an attempt to damage the morale of the Boer Army.

Krüger's son Jan (Werner Hinz), who has pro-British sentiments due to his Oxford education, visits a concentration camp to find his wife, Petra (Gisela Uhlen). He is caught and hanged, with his wife watching. When the women respond in anger, they are massacred.

The flashback concludes in the Geneva hotel room. Krüger prophesies the destruction of Britain by major world powers, which will make the world a better place to live in.

Propaganda message

Ohm Krüger was one of a number of anti-British propaganda feature films produced by the Nazis during the war, most of which focused on the theme of colonialism to demonstrate through Britain's history the true nature of the British character.[2] Some of these productions, such as Der Fuchs von Glenarvon (1940) and Mein Leben für Irland (1941), represented British relations with Ireland.[3] Other works criticized its imperialism toward the Afrikaans-speaking Boers, of which Ohm Krüger was the most expensive and powerful.[4] It used the Boer War to present the British as violent, exploitative, and an enemy to civilisation.[5] In doing so, it was able to complement the anti-imperalist views of the press, appeal to the German public's interest in colonial issues, and build upon the hatred of the British that had grown with RAF bombing raids on German targets.[6] It was one of a number of films intended to prepare Germany for a planned invasion of Britain.[7] Its somewhat crude attack on Britain is typical of later films, such as Carl Peters, after Hitler came to the conclusion that no separate peace with Britain was possible.[8] It depicts the British as seeking gold, symbolic of barrenness and evil, in contrast to the Boers who raise crops and animals. Kruger's son decides to obey Kruger after the son's wife has been raped.[9]

Publicity material which accompanied the film particularly drew attention to the role of Winston Churchill in the Boer Wars, during which he served as a journalist.[10] Tobis also advised the press to emphasise 'what Churchill learnt in the Boer War':

'The same Churchill who in South Africa saw his ideas about exterminating the Boers followed throughout, as the English rulers, voicing polished humanitarian slogans, while driven by mere greed, unleashed the most contemptible actions on a people under attack. [T]he same Churchill is now Albion's prime minister.[11]

British concentration camps were portrayed in the film as intentionally inhumane. (Meanwhile, major expansion of the Nazi camp system was being implemented.[12]

Parallels were drawn between the Boer War and the Second World War, and between Paul Krüger and Adolf Hitler.

Key British figures are demonised in the film, including Joseph Chamberlain and the then Prince of Wales (later Edward VII). Queen Victoria is presented as a drunkard and the British concentration camp commandant, responsible for the killing of female inmates, resembles Winston Churchill.

It also reflects German anger at the loss of all German colonies at the end of World War I, though less directly than Carl Peters.[13]

Production

The first outline for Ohm Krüger was begun in September 1940 by Hans Steinhoff and Harald Bratt.[14]

The film had very high production costs of over 5.5 million Reichmarks.[15] At the time, Joseph Goebbels had been encouraging film-makers to have lower production costs, but he made an exception for Ohm Krüger, declaring it to be reichswichtig (important for the State) due to its propagandistic and artistic value; in his Diaries Goebbels - at the "first showing of the completed Ohm Krüger" at his house - wrote: "Great excitement. The film is unique. A really big hit. Everyone is thrilled by it. Jannings has excelled himself. An anti-England film beyond one's wildest dreams. Gauleiter Eigruber is also present and very enthusiastic".[16][17] The production used 4000 horses, about 200 oxen, 180 ox wagons, 25,000 soldiers and 9000 women. [18]

Reception

Publicity and press coverage

Directives were issued to the press by the RMVP about how to cover the film. They were instructed to draw attention to the significance of the film, but to emphasise its aesthetic rather than its political content.[19]

Audience response

The film had its première on 4 April 1941, two days after being passed by the Censor.[20] It was well-received, attracting a quarter of a million viewers in four days upon its initial release, largely as a result of the high expectations generated by the propaganda press campaign, with word-of-mouth recommendations also being important in the film's popularity.[21]

The Sicherheitsdienst (SD; Nazi intelligence service) reported that the film exceeded expectations, with audiences particularly praising the 'unity of political conviction, artistic expression and acting performances'. The public were also reportedly impressed by the fact that a film of Ohm Krüger's quality could be produced in wartime.[22] The film was particularly popular with young audiences, according to both SD reports and film surveys.[23]

Some, however, did question the authenticity of the film.[24]

Internationally, the film was officially released in only eight independent states (including Italy), all of which were closely linked to Nazi Germany, and in France (first in the occupied zone, later also in Vichy France).[25]

Awards and honours

Ohm Krüger won the Mussolini Cup for best foreign film at the 1941 Venice Film Festival, at which the Italian Minister for Popular Culture, Alessandro Pavolini, praised particularly the film's propaganda value and the role of Emil Jannings.[26]

Within Germany, the film was the first to be given the honorary distinction 'Film of the Nation' (Film der Nation) by the Reich Propaganda Ministry Censorship Office.[27] Only three other films received this rating, namely Heimkehr (1941), The Great King (1942) and Die Entlassung (1942).[28] Joseph Goebbels also presented Emil Jannings with the 'Ring of Honour of the German Cinema'.[29]

Re-release

The success of the film led Goebbels to re-release it in October 1944, as inspiration for the Volkssturm.[30] On 31 January 1945, the film was banned, for fear that the morale of German audiences would be harmed by images of Boer refugees whose houses had been destroyed - 'images that by the time replicated the harsh realities of everyday life in Germany'.[31]

References

- ↑ Welch, Propaganda, p. 231.

- ↑ Fox, Film Propaganda, pp. 166, 171.

- ↑ Erwin Leiser, Nazi Cinema p97 ISBN 0-02-570230-0

- ↑ Robert Edwin Hertzstein, The War That Hitler Won p344-5 ISBN 0-399-11845-4

- ↑ Welch, Propaganda, p. 229.

- ↑ Fox, Film Propaganda, p. 172; Welch, Propaganda, p. 230.

- ↑ Welch, Propaganda, p. 230.

- ↑ Erwin Leiser, Nazi Cinema p99 ISBN 0-02-570230-0

- ↑ Richard Grunberger, The 12-Year Reich, p 380-1, ISBN 0-03-076435-1

- ↑ Fox, Film propaganda, p. 173.

- ↑ Quoted in Fox, Film propaganda, p. 173.

- ↑ Pierre Aycoberry The Nazi Question, p11 Pantheon Books New York 1981

- ↑ Claudia Koonz, The Nazi Conscience, p. 205 ISBN 978-0-674-01172-4

- ↑ Welch, Propaganda, p. 230.

- ↑ Welch, Propaganda, p. 231.

- ↑ The Goebbels Diaries, 1939-1941, edited and translated by Fred Taylor, Hamish Hamilton, 1982, p. 293

- ↑ Welch, Propaganda, p. 231.

- ↑ Berlynsche Tydingen No 1941, 4 April 1941 p.4

- ↑ Welch, Propaganda, p. 234.

- ↑ Welch, Propaganda, p. 229.

- ↑ Fox, Film propaganda, p. 182.

- ↑ Fox, Film propaganda, p. 182.

- ↑ Fox, Film Propaganda, p. 184; Welch, Propaganda, p. 235.

- ↑ Fox, Film Propaganda, p. 183.

- ↑ Vande Winkel, Ohm Krüger's Travels, pp. 116-120.

- ↑ Fox, Film Propaganda, pp. 183-184.

- ↑ Welch, Propaganda, p. 229.

- ↑ Hake, German National Cinema, p. 63.

- ↑ Welch, Propaganda, p. 229.

- ↑ Fox, Film Propaganda, p. 184; Welch, Propaganda, p. 235.

- ↑ Vande Winkel, Ohm Krügers Travels, p. 121.

Bibliography

- Fox, Jo, Film Propaganda in Britain and Nazi Germany

- Hake, Sabine, German National Cinema

- Hallstein, C.W., 'Ohm Kruger: The Genesis of a Nazi Propaganda Film', Literature Film Quarterly (2002)

- Klotz, M, 'Epistemological ambiguity and the fascist text: Jew Süss, Carl Peters, and Ohm Krüger', New German Critique, 74 (1998)

- Taylor, Richard, Film Propaganda: Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany

- Vande Winkel, R, 'Ohm Krüger's Travels: a Case Study in the Export of Third-Reich Film Propaganda', Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques, 35:2 (2009), pp. 108–124.

- Welch, David, Propaganda and the German Cinema, 1939-1945

External links

- Ohm Krüger at the Internet Movie Database

- Ohm Krüger at the Internet Archive