Old Russian Law

Old Russian Law or Russian Law is a legal system in Kievan Rus' (since the 9th century), in later Old Rus' states (knyazhestva, or princedoms in the period of feudal fragmentation), in Grand Duchy of Lithuania and in Moscow Rus' (see: Grand Duchy of Moscow and Tsardom of Russia). Main source was Old Slavic customary law: Zakon Russkiy (Law of Rus') (it was partly written in Rus'–Byzantine Treaties). Another sources were Old Scandinavian customary law (see: Varangians) and Byzantine law (since the 10th century).[1]

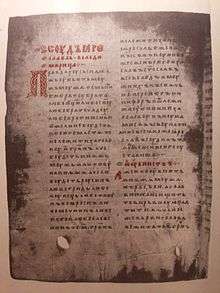

The main written sources were Russkaya Pravda ("Russian Justice") (since the 11th century) and Statutes of Lithuania (since the 16th century).[2]

History

Ryad

According to Old Russian chronicles, in 862, Slavs and Finns invited Varangians under the leadership of prince Rurik to rule in their land:

They said to themselves, "Let us seek a prince who may rule over us and judge us according to the Law." They accordingly went overseas to the Varangian Russes: these particular Varangians were known as Russes, just as some are called Swedes, and others Normans, English, and Gotlanders, for they were thus named. The Chuds, the Slavs, the Krivichians, and the Ves' then said to the people of Rus', "Our land is great and rich, but there is no order in it. Come to rule and reign over us."

Early Russian state settled on the oral treaty, or "ryad" (Old Russian: рядъ) between the prince (knyaz) with his armed force (druzhina) on the one hand, and tribal "nobility" and formally all people on the other hand. The prince and his druzhina defended people, decide lawsuits, provided trade and built towns. And people paid tribute and took part in irregular military. During the ensuing centuries the ryad was playing an important role in Old Russian princedoms: the prince and his administration (druzhina) found their relationship with people ("all land", "all townsmen" in Old Russian chronicles) on the treaty. A breach of the treaty could result in exile of the prince (Izyaslav Yaroslavich and Vsevolod Yaroslavich) or even in murder of the prince (Igor Rurikovich and Igor Olgovich).[4][5][6]

Written secular law [7][8][9]

One of the result of Rus'–Byzantine Wars was conclusion of Treaties with Byzantine in the 10th century, where, apart from Byzantine legal rules, also Zakon Russkiy (Law of Rus') - rules of Old Russian oral customary law reflected.

Yaroslav's Pravda of the beginning of the 11th century was the first written law in Rus'. This short code regulated the relationship between the princely druzhina ("rusins") and the people ("slovenins") concerning criminal law. After Yaroslav's death, his sons Izyaslav, Vsevolod, Svyatoslav and their druzhina got together and promulgated a code concerning the violation of property rights in princely lands (Pravda of Yaroslav's sons) in the middle of the 11th century. Yaroslav's Pravda and Pravda of Yaroslav's sons became a basis for the Short edition of Russkaya Pravda.

In the period of Vladimir Monomakh's reign at the beginning of the 12th century, the Vast edition of Russkaya Pravda was given, which contained rules of criminal, procedural and civil law, including trade, family law and rules of the bond of obligation.

Later written secular law also included statutory charters, trade treaties, statutes of Grand Duchy of Lithuania, big codes of Moscow Rus' - Sudebniks (see below), and other texts.

Byzantine law and church law

Translations of Byzantine legal codes, including Nomocanon, were widely spread in Old Rus' (see: Kormchaia, Merilo Pravednoye),[10] but it wasn't widely applied in secular or church legal practice, restricted mainly in canon law. The Church in Old Rus' did not have wide influence and depended on the power of the state. Thus, church law mainly dealt with family law and sanctions against moral violation.[11]

See also: church statutes of prince Vladimir and prince Yaroslav.

Main sources[2]

Oral sources

- Customary law: Zakon Russkiy (Law of Rus') in Rus'–Byzantine Treaties.

Written sources

Foreign sources

- Byzantine law, including Nomocanon.

- Zakon Sudnyi Liudem

Native sources

It was in part a record of oral law and revision of foreign sources:

- Rus'–Byzantine Treaties

- Russkaya Pravda

- Church Statute of Prince Vladimir

- Church Statute of Prince Yaroslav

- Local church statutes

- Statutory Charters

- Smolensk Trade Treaty of 1229

- Novgorod's Treaties

- Pravosudie mitropolichye

- Novgorod Judicial Charter of the 15th century

- Pskov Judicial Charter of 1467

- Sudebnik of 1497

- Statutes of Lithuania

- Sudebnik of 1550

- Stoglav of 1551

- Sudebnik of 1589

- Sobornoye Ulozheniye of 1607

- Sobornoye Ulozheniye of 1649

Some collections of law

- Kormchaia

- Merilo Pravednoye

- Collections in supplement of Old Russian Chronicles[12]

Notes

- ↑ Kaiser, Daniel H. The growth of the law in Medieval Russia. – Princeton: Princeton univ. press, 1980. – 308 p.

- 1 2 Memorials of Russian Law. Issue 1-7. - Moscow, 1952-. (Russian: Памятники русского права. – М., 1952-. – Вып. 1-7.)

- ↑ Samuel Hazzard Cross (1953). Samuel Hazzard Cross; Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor, eds. The Russian Primary chronicle: Laurentian text (PDF). Medieval Academy of America. p. 59.

- ↑ Melnikova, Elena. Petrukhin, Vladimir. "The Legend of the Varangians Invitation" in comparative historical perspective // 11th All-Union Conference on the Study of History, Economics, Literature and Language of the Scandinavian countries and Finland / ed. by Yuriy Andreev and others. - Moscow, 1989. - Issue 1. - P. 108–110. (Russian: Мельникова Е.А., Петрухин В.Я. «Легенда о призвании варягов» в сравнительно-историческом аспекте // XI Всесоюзная конференция по изучению истории, экономики, литературы и языка Скандинавских стран и Финляндии / редкол.: Ю.В. Андреев и др. – М., 1989. – Вып. 1. – С. 108–110).

- ↑ Melnikova, Elena. Ryad in the Legend of the Varangians Invitation and its European and Scandinavian Parallels // Melnikova, Elena. Old Rus' and Scandinavia: Selected Works / ed. by G. Glazyrina and Tatyana Dzhakson. - Moscow, 2011. – С. 249–256. (Russian: Мельникова Е.А. Ряд в Сказании о призвании варягов и его европейские и скандинавские параллели // Мельникова Е.А. Древняя Русь и Скандинавия: Избранные труды / под ред. Г.В. Глазыриной и Т.Н. Джаксон. – М.: Русский Фонд Содействия Образованию и Науке, 2011. – С. 249–256).

- ↑ Petrukhin, Vladimir. Rus' in the 9-10th centuries. From Varangians Invitation to the Сhoice of Faith / 2nd edition, corrected and supplemented. Moscow, 2014. Russian: Петрухин В.Я. Русь в IX—X веках. От призвания варягов до выбора веры / Издание 2-е, испр. и доп. - М.: ФОРУМ: Неолит, 2014).

- ↑ Dyakonov, Mikhail. Essays on Social and Political System of Old Rus' / 4th edition, corrected and supplemented. - Saint Petersburg, 1912. – XVI, 489 p. (Russian: Дьяконов М.А. Очерки общественного и государственного строя Древней Руси / Изд. 4-е, испр. и доп. – СПб.: Юридич. кн. склад Право, 1912. – XVI, 489 с.).

- ↑ Yushkov, Serafim. Course of the History of State and Law of the USSR. - Moscow: Yurizdat (Juridical Publisher), 1949. - Vol. 1: Social and Political System and Law of Kievan State. - 542 p. (Russian: Юшков С.В. Курс истории государства и права СССР. – М.: Юриздат, 1949. – Т. I: Общественно-политический строй и право Киевского государства. – 542 с..

- ↑ Zimin, Aleksandr. Pravda Russkaya. - Moscow: Drevlekhranilische ("Archive"), 1999. – 421 p. (Russian: Зимин А.А. Правда Русская. – М.: Древлехранилище, 1999. – 421 с.).

- ↑ Schapov, Yaroslav. Byzantine and South Slavic Legal Heritage in Rus' at 11-13th centuries / ed. by Lev Cherepnin. - Moscow: Nauka, 1978. – 290 p. (Russian: Щапов Я.Н. Византийское и южнославянское правовое наследие на Руси в XI–XIII вв. / отв. ред. Л.В. Черепнин. – М.: Наука, 1978. – 290 с.).

- ↑ Zhivov, Viktor. The History of Russian Law as a Linguistic and Semiotic Problem // Zhivov, Viktor. Investigations in the Field of History and Prehistory of Russian Culture. - Moscow: Yazyki Slavyanskoy Kultury ("Languages of Slavic culture"), 2002. – P. 187–305. (Russian: Живов В.М. История русского права как лингвосемиотическая проблема // Живов В.М. Разыскания в области истории и предыстории русской культуры. – М.: Языки славянской культуры, 2002. – С. 187–305).

- ↑ Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles: Russian: Полное собрание русских летописей. — СПб.; М, 1843; М., 1989. — Т. 1—38.

Some editions of sources

- English translations of the Laws of Rus': Source: The Laws of Rus' - Tenth to Fifteenth Centuries, tr., ed. Daniel H. Kaiser (Salt Lake City: Charles Schlacks Publisher, 1992).

- Memorials of Russian Law. Issue 1-7. - Moscow, 1952-. (Russian: Памятники русского права. – М., 1952-. – Вып. 1-7.).

- Russian Legislation of 10th-20th centuries / ed. by Oleg Chistyakov. Moscow: Yuridichtskaya Literatura ("Juridical Literature"), 1984-. - Vol. 1-4. (Russian: Российское законодательство X–XX веков: в 9 т. / Под общ. ред. О.И. Чистякова. – М.: Юрид. лит., 1984-. - Том 1-4).

- Main edition of Russkaya Pravda: Pravda Russkaya / ed. by Boris Grekov. - Moscow; Leningrad: publisher of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. - Vol. 1: Texts. - 1940. Vol. 2: Commentaries. - 1947. Vol. 3: Facsimile of the texts. - 1963. (Russian: Правда Русская / Под общ. ред. акад. Б.Д. Грекова. - М.; Л.: Изд-во АН СССР. - Т. I: Тексты. - 1940; Т. II: Комментарии. - 1947; Т. III: Факсимильное воспроизведение текстов. - 1963).

- Old Russian Princely Statutes of the 11-15th centuries / Yaroslav Schapov. - Moscow: Nauka, 1976. - 239 p. (Russian: Древнерусские княжеские уставы XI–XV вв. / Изд. подготовил Я.Н. Щапов. – М.: Наука, 1976. – 239 с.).

- (Russian) Tikhomirov, Mikhail, A study of Russkaya Pravda.

English references

- Vernadsky, George. Medieval Russian Laws. – NY: Columbia University Press, 1947. – 106 p.

- Kaiser, Daniel H. The growth of the law in Medieval Russia. – Princeton: Princeton univ. press, 1980. – 308 p.

- Feldbrugge, Ferdinand Joseph Maria. Law in Medieval Russia. - Leiden– Boston, 2009.

- Padokh, Yaroslav. Ruskaia Pravda. // Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Vol. 4. 1993.