One-way traffic

One-way traffic (or uni-directional traffic) is traffic that moves in a single direction. A one-way street is a street either facilitating only one-way traffic, or designed to direct vehicles to move in one direction. One-way streets typically result in higher traffic flow as drivers may avoid encountering oncoming traffic or turns through oncoming traffic. Residents may dislike one-way streets due to the circuitous route required to get to a specific destination, and the potential for higher speeds adversely affecting pedestrian safety. Some studies even challenge the original motivation for one-way streets, in that the circuitous routes negate the claimed higher speeds.[1]

Signage

General signs

Signs are posted showing which direction the vehicles can move in: commonly an upward arrow, or on a T junction where the main road is one-way, an arrow to the left or right. At the end of the street through which vehicles may not enter, a prohibitory traffic sign "Do Not Enter", "Wrong Way", or "No Entry" sign is posted, e.g. with that text, or a round red sign with a white horizontal bar. Sometimes one portion of a street is one-way, another portion two-way. An advantage of one-way streets is that drivers do not have to watch for vehicles coming in the opposite direction on this type of street.

No entry signs

The abstract "No Entry" sign was officially adopted for standardization at the League of Nations convention in Geneva in 1931. The sign was adapted from Swiss usage, derived from the practice of former European states that marked their boundaries with their formal shield symbols. Restrictions on entry were indicated by tying a blood-red ribbon horizontally around the shield. The sign is also known as C1, from its definition in the Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals.

The European "No Entry" sign was adopted into North American uniform signage in the 1970s, replacing a previous white rectangular sign bearing only the English text "Do Not Enter". In addition to the standardized graphic symbol, the US version still retains the wording "Do Not Enter", while the European and Canadian versions typically have no text.

Since Unicode 5.2, the Miscellaneous Symbols block contains the glyph ⛔ (U+26D4 NO ENTRY), representable in HTML as ⛔ or ⛔.

.svg.png) The contemporary Australian one way sign is vertically oriented, but older signs similar to those used in North America are still common.

The contemporary Australian one way sign is vertically oriented, but older signs similar to those used in North America are still common. One-way road sign used in Russia

One-way road sign used in Russia Sign used in Russia to indicate end of one-way traffic

Sign used in Russia to indicate end of one-way traffic "No entry" signs are often placed at the exit ends of one-way streets

"No entry" signs are often placed at the exit ends of one-way streets A Swedish one-way sign used on T junctions

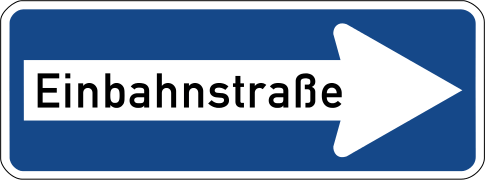

A Swedish one-way sign used on T junctions Some countries, like Germany, show text on one-way signs (Einbahnstraße means "one-way street")

Some countries, like Germany, show text on one-way signs (Einbahnstraße means "one-way street")

Applications

One-way streets may be part of a one-way system, which facilitates a smoother flow of motor traffic through, for example, a city center grid; as in the case of Bangalore, India. This is achieved by arranging one-way streets that cross in such a fashion as to eliminate right turns (for driving on left) or left turns (for driving on right). Traffic light systems at such junctions may be simpler and may be coordinated to produce a green wave.

Some of the reasons one-way traffic is specified:

- The street is too narrow for movement in both directions and the road users unable to coordinate easily

- Prevent drivers from cutting through residential streets to bypass traffic lights or other requirements to stop (a so-called "rat run")

- Discourage drivers from cruising through a residential neighborhood (e.g. by having mostly one-way streets pointing outwards, with relatively few vehicular entrances)

- Part of a one-way pair of two parallel one-way streets in opposite directions (such as a divided highway)

- For a proper functioning of a system of paid parking or other restricted vehicular access (these may also use one-way treadles which puncture tires if traversed in the forbidden direction)

- To calm traffic, especially in historic city centers

- Eliminate turns that involve crossing in front of oncoming traffic

- Increase traffic flow and potentially reduce traffic congestion

- Eliminate the need for a center turn lane that can instead be used for travel

- Better traffic flow in densely built-up areas where road widening may not be feasible

- Simplify pedestrian crossing of the street due to walkers only needing to look for oncoming traffic in one direction

- Eliminate cars' driver-side doors opening into the travel lane in parallel parking spaces for parking lanes located on the left (right-hand drive) or right (left-hand drive) side of a street

- Locate a one-way bike lane on the opposite side of the street from parallel parking spaces to prevent dooring

- Limited-access highway entrance and exit ramps.

Left turn on red

In the United States, 37 states and Puerto Rico allow left turns on red only if both the origin and destination streets are one way. See South Carolina law[2] Section 56-5-970 C3, for example. Five other states, namely Alaska, Idaho, Michigan, Oregon, and Washington, allow left turns on red onto a one-way street even from a two-way street.[3][4][5][6]

History

An attempt was apparently made in 1617 to introduce one-way streets in alleys near the River Thames in London.[7][8] The next one-way street in London was Albemarle Street in Mayfair, the location of the Royal Institution. It was so designated in 1800 because the public science lectures were so popular there.[9] The first one-way streets in Paris were the Rue de Mogador and the Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin, created on 13 December 1909.

One story of the origin of the one-way street in the United States originated in Eugene, Oregon. On 9 September 1934, the on-fire SS Morro Castle[10] was towed to the shore near the Asbury Park Convention Center and the sightseeing traffic was enormous. The Asbury Park Police Chief decided to make the Ocean Avenue one-way going north and the street one block over (Kingsley) in one-way going south, creating a circular route. By the 1950s this "cruising the circuit" became a draw to the area in itself since teens would drive around it looking to hook up with other teens. The circuit was in place until the streets went back to two way in 2007 due to new housing and retail development.

One-way traffic of pedestrians

Sometimes one-way walking is specified for smooth pedestrian traffic flow, or in the case of entrance checks (such as ticket checks) and exit checks (e.g. the check-out in a shop). They may be outdoors (e.g. an extra exit of a zoo), or in a building, or in a vehicle (e.g. a tram). In addition to signs, there may be various forms and levels of enforcement, such as:

- personnel; sometimes a "soft" traffic control system is supported by vigilant staff monitoring

- a turnstile; however, turnstile jumping is possible

- a High Entrance/Exit Turnstile (HEET)

- a one-way revolving door

- an escalator; however, the escalator can be traversed in opposite direction, by walking up or down the stairs faster than it moves

- a door or gate that can only be opened from one side (a manual or electric lock, or simply a door that is pushed open and has no doorknob on the other side), or which automatically opens from one side. (However, with help from someone on the other side, it may often be bypassed in the reverse direction.)

- entrance of a shop

- an emergency exit, which may activate an alarm

Sometimes a door or gate can be opened freely from one side, and only with a key or by inserting a coin from the other side (house door, door with a coin slot, e.g. giving entrance to a pay toilet). The latter can be passed without paying when somebody else leaves, and by multiple persons if only one pays (as opposed to a coin-operated turnstile).

References

- ↑ Jaffe, Eric. "The Case Against One-Way Streets". The Atlantic Cities. Atlantic Media Company. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ↑ scstatehouse.gov Archived November 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ touchngo.com

- ↑ legislature.idaho.gov

- ↑ legislature.mi.gov

- ↑ apps.leg.wa.gov

- ↑ Homer, Trevor (2006). The Book of Origins. London: Portrait. pp. 283–4. ISBN 0-7499-5110-9.

- ↑ Penguin Pocket On This Day. Penguin Reference Library. 2006. ISBN 0-14-102715-0.

- ↑ Singh, Simon. "Stars In Whose Eyes?". Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to One-way traffic road signs. |