Orientalizing period

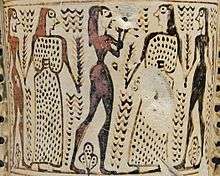

In the Archaic phase of ancient Greek art and of Greek-inspired art, the Orientalizing period is the cultural and art historical period which started during the later part of the 8th century BCE, when there was a heavy influence from the more advanced art of the Eastern Mediterranean and Ancient Near East. The main sources were Syria and Assyria, and to a lesser extent Phoenicia, Israel, and Egypt; though motifs were adapted, making it rarely possible to point to a single clear source.[1] It encompasses a new, Orientalizing style, spurred by a period of increased cultural interchange in the Aegean world. The period is characterized by a shift from the prevailing Geometric style to a style with different sensibilities, which were inspired by the East. The intensity of the cultural interchange during this period is sometimes compared to that of the Late Bronze Age.

Among surviving artefacts, the main effects are seen in painted pottery and metalwork, as well as engraved gems. Monumental and figurative sculpture was less affected,[2] and there the new style is often called Daedelic. A new type of face is seen, especially on Crete, with "heavy, overlarge features in a U- or V-shaped face with horizontal brow"; these derive from the Near East.[3] Pottery provides much the greatest number of examples, and shows three types of new motifs: animal, vegetable and abstract,[4] with much of the vegetable repertoire tending to be highly stylised.

Vegetable motifs such as the palmette, lotus and tendril volute were to remain characteristic of Greek decoration, and through it were transmitted through most of Eurasia. Exotic animals and monsters, in particular the lion (not native to Greece itself even by this period) and sphinxes were added to the griffin, already found at Knossos.[5]

The period from roughly 750 to 580 BCE also saw a comparable Orientalizing phase of Etruscan art, as a rising economy encouraged Etruscan families to acquire foreign luxury products incorporating Eastern-derived motifs.[6] At this time Carian art and pottery also passed through Orientalizing.[7]

Background

During this period, the Assyrians advanced along the Mediterranean coast, accompanied by Greek and Carian mercenaries, who were also active in the armies of Psamtik I in Egypt. The new groups started to compete with established Mediterranean merchants. In other parts of the Aegean world similar population moves occurred. Phoenicians and Jews settled in Cyprus and in western regions of Greece, while Greeks established trading colonies at Al Mina, Syria, and in Ischia (Pithecusae) off the Tyrrhenian coast of Italy. These interchanges led to a period of intensive borrowing in which the Greeks (especially) adapted cultural features from the Semitic East into their art.[8]

New materials and skills

Massive imports of raw materials, including metals, and a new mobility among foreign craftsmen caused new craft skills to be introduced in Greece. In The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age, Walter Burkert described the new movement in Greek art as a revolution: "With bronze reliefs, textiles, seals, and other products, a whole world of eastern images was opened up which the Greeks were only too eager to adopt and adapt in the course of an "orientalizing revolution".[9] Many Greek myths originated in attempts to interpret and integrate foreign icons in terms of Greek cult and practice. "Oriental" motifs such as sphinxes, lions and lotuses began to be included on Greek wares.[10]

In bronze and terracotta figurines, the introduction from the east of the mould led to a great increase in production, of figures mainly made as votive offerings.[11]

Impact on myth and literature

Some Greek myths reflect Mesopotamian literary classics.[12] has argued that it was migrating seers and healers who transmitted their skills in divination and purification ritual along with elements of their mythological wisdom. He has suggested direct literary Eastern influence in the Homeric literature. The intense encounter during the orientalizing period also accompanied the invention of the Greek alphabet and the Carian alphabet, based on the earlier phonetic but unpronounceable Levantine writing, which caused a spectacular leap in literacy and literary production, as the oral traditions of the epic began to be transcribed onto imported Egyptian papyrus (and occasionally leather).

The Orientalizing style in pottery

In Attic pottery, the distinctive Orientalizing style known as "proto-Attic" was marked by floral and animal motifs; it was the first time discernibly Greek religious and mythological themes were represented in vase painting. The bodies of men and animals were depicted in silhouette, though their heads were drawn in outline; women were drawn completely in outline. At the other important center of this period, Corinth, the orientalizing influence started earlier, though the tendency there was to produce smaller, highly detailed vases in the "proto-Corinthian" style that prefigured the black-figure technique.[13]

Cultural predominance of the East, identified archaeologically by pottery, ivory and metalwork of eastern origin found in Hellenic sites, soon gave way to thorough Hellenization of imported features in the Archaic Period that followed. In the West, Etruscan civilization passed through an Orientalizing period approximately at the same time, ca. 730-580 BCE.

From the mid-sixth century, the growth of Achaemenid power in the eastern end of the Aegean and in Asia Minor, reduced the quantity of eastern goods found in Greek sites, as the Persians began to conquer Greek cities in Ionia, along the coast of Asia Minor.

Notes

- ↑ Cook, 39

- ↑ Cook, 5-6

- ↑ Boardman (1993), 16 (quoted), 17, 29, 33

- ↑ Cook, 39

- ↑ Boardman (1993), 15-16

- ↑ Fred S. Kleiner, ed. Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective 2010:14.

- ↑ Cook, R.M. (1999). "A List of Carian Orientalising Pottery". Oxford Journal of Archeology. 18: 79–93.

- ↑ Burkert, 128 et passim

- ↑ Burkert, 128

- ↑ "The evolution of Greek vase painting", Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology, 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Boardman (1993), 15

- ↑ Burkert, 41-88

- ↑ Cook, 39-51

References and sources

- Bettancourt, Philip, "The Age of Homer: An Exhibition of Geometric and Orientalizing Greek Art", pdf review, Penn Museum, 1969

- Boardman, John ed. (1993), The Oxford History of Classical Art, 1993, OUP, ISBN 0198143869

- Boardman, J. (1998), Early Greek Vase Painting: 11th-6th centuries BC, 1998

- Burkert, W. The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age, 1992.

- Cook, R.M., Greek Art, Penguin, 1986 (reprint of 1972), ISBN 0140218661

- Payne, H., Protocorinthian Vase-Painting, 1933

Further reading

- Von Bothmer, Dietrich (1987). Greek vase painting. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870990845.

- Sideris A., "Orientalizing Rhodian Jewellery", Cultural Portal of the Aegean Archipelago, Athens 2007.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Greek Orientalizing pottery. |