Ouija

| Part of a series on |

| Spiritualism |

|---|

| Practices |

| Related topics |

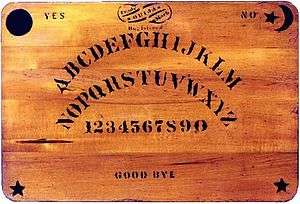

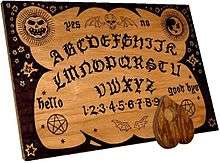

The ouija (wee-jah, or wee-jee), also known as a spirit board or talking board is a flat board marked with the letters of the alphabet, the numbers 0–9, the words "yes", "no", "hello" (occasionally), and "goodbye", along with various symbols and graphics. It uses a small heart-shaped piece of wood or plastic called a planchette. Participants place their fingers on the planchette, and it is moved about the board to spell out words. "Ouija" is a trademark of Hasbro, Inc.,[1] but is often used generically to refer to any talking board.

Following its commercial introduction by businessman Elijah Bond on July 1, 1890,[1] the Ouija board was regarded as a parlor game unrelated to the occult until American Spiritualist Pearl Curran popularized its use as a divining tool during World War I.[2] Spiritualists believed that the dead were able to contact the living and reportedly used a talking board very similar to a modern Ouija board at their camps in Ohio in 1886 to ostensibly enable faster communication with spirits.[3]

Some Christian denominations have "warned against using Ouija boards", holding that they can lead to demonic possession.[4][5] Occultists, on the other hand, are divided on the issue, with some saying that it can be a positive transformation; others reiterate the warnings of many Christians and caution "inexperienced users" against it.[4]

Paranormal and supernatural beliefs associated with Ouija have been harshly criticized by the scientific community, since they are characterized as pseudoscience. The action of the board can be parsimoniously explained by unconscious movements of those controlling the pointer, a psychophysiological phenomenon known as the ideomotor effect.[6][7][8][9]

History

China

One of the first mentions of the automatic writing method used in the Ouija board is found in China around 1100 AD, in historical documents of the Song Dynasty. The method was known as fuji (扶乩), "planchette writing". The use of planchette writing as an ostensible means of necromancy and communion with the spirit-world continued, and, albeit under special rituals and supervisions, was a central practice of the Quanzhen School, until it was forbidden by the Qing Dynasty.[10] Several entire scriptures of the Daozang are supposedly works of automatic planchette writing. According to one author, similar methods of mediumistic spirit writing have been practiced in ancient India, Greece, Rome, and medieval Europe.[11]

Talking boards

As a part of the spiritualist movement, mediums began to employ various means for communication with the dead. Following the American Civil War in the United States, mediums did significant business in presumably allowing survivors to contact lost relatives. The Ouija itself would be created and named in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1890, but the use of talking boards was so common by 1886 that news reported the phenomenon taking over the spiritualists' camps in Ohio.[3]

Commercial parlor game

Businessman Elijah Bond had the idea to patent a planchette sold with a board on which the alphabet was printed, much like the previously existing talking boards. The patentees filed on May 28, 1890 for patent protection and thus are credited with the invention of the Ouija board. Issue date on the patent was February 10, 1891. They received U.S. Patent 446,054. Bond was an attorney and was an inventor of other objects in addition to this device.

An employee of Elijah Bond, William Fuld, took over the talking board production. In 1901, Fuld started production of his own boards under the name "Ouija".[12] Charles Kennard (founder of Kennard Novelty Company which manufactured Fuld's talking boards and where Fuld had worked as a varnisher) claimed he learned the name "Ouija" from using the board and that it was an ancient Egyptian word meaning "good luck." When Fuld took over production of the boards, he popularized the more widely accepted etymology: that the name came from a combination of the French and German words for "yes".[13]

The Fuld name would become synonymous with the Ouija board, as Fuld reinvented its history, claiming that he himself had invented it. The strange talk about the boards from Fuld's competitors flooded the market, and all these boards enjoyed a heyday from the 1920s through the 1960s. Fuld sued many companies over the "Ouija" name and concept right up until his death in 1927. In 1966, Fuld's estate sold the entire business to Parker Brothers, which was sold to Hasbro in 1991, and which continues to hold all trademarks and patents. About ten brands of talking boards are sold today under various names.[12]

Scientific investigation

The Ouija phenomenon is considered by the scientific community to be the result of the ideomotor response.[6][14][15][16] Since 1853 this effect was described by Michael Faraday on table-turning.[17][18]

Various studies have been produced, recreating the effects of the Ouija board in the lab and showing that, under laboratory conditions, the subjects were moving the planchette involuntarily.[14][19] Skeptics have described Ouija board users as 'operators'.[20] Some critics noted that the messages ostensibly spelled out by spirits were similar to whatever was going through the minds of the subjects.[21] According to Professor of neurology Terence Hines in his book Pseudoscience and the Paranormal (2003):

The planchette is guided by unconscious muscular exertions like those responsible for table movement. Nonetheless, in both cases, the illusion that the object (table or planchette) is moving under its own control is often extremely powerful and sufficient to convince many people that spirits are truly at work... The unconscious muscle movements responsible for the moving tables and Ouija board phenomena seen at seances are examples of a class of phenomena due to what psychologists call a dissociative state. A dissociative state is one in which consciousness is somehow divided or cut off from some aspects of the individual's normal cognitive, motor, or sensory functions.[22]

In the 1970s Ouija board users were also described as "cult members" by sociologists, though this was severely scrutinised in the field.[23]

Ouija boards have been criticized in the press since their inception, having been variously described as "'vestigial remains' of primitive belief-systems" and a con to part fools from their money.[24] Some journalists have described reports of Ouija board findings as 'half truths' and have suggested that their inclusion in national newspapers lowers the national discourse overall.[25]

Use in creation of literature

Ouija boards have been the source of inspiration for literary works, used as guidance in writing or as a form of channeling literary works. As a result of Ouija boards' becoming popular in the early 20th century, by the 1920s many "psychic" books were written of varying quality often initiated by Ouija board use.[26]

Emily Grant Hutchings claimed that her novel Jap Herron: A Novel Written from the Ouija Board (1917) was dictated by Mark Twain's spirit through the use of a Ouija board after his death.[27]

Pearl Lenore Curran (February 15, 1883 – December 4, 1937), alleged that for over 20 years she was in contact with a spirit named Patience Worth. This symbiotic relationship produced several novels, and works of poetry and prose, which Pearl Curran claimed were delivered to her through channelling Worth's spirit during sessions with a Ouija board, and which works Curran then transcribed.

In late 1963, Jane Roberts and her husband Robert Butts started experimenting with a Ouija board as part of Roberts' research for a book on extra-sensory perception.[28] According to Roberts and Butts, on December 2, 1963 they began to receive coherent messages from a male personality who eventually identified himself as Seth, culminating in a series of books dictated by "Seth".

In 1982, poet James Merrill released an apocalyptic 560-page epic poem entitled The Changing Light at Sandover, which documented two decades of messages dictated from the Ouija board during séances hosted by Merrill and his partner David Noyes Jackson. Sandover, which received the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1983,[29] was published in three volumes beginning in 1976. The first contained a poem for each of the letters A through Z, and was called The Book of Ephraim. It appeared in the collection Divine Comedies, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1977.[30] According to Merrill, the spirits ordered him to write and publish the next two installments, Mirabell: Books of Number in 1978 (which won the National Book Award for Poetry)[31] and Scripts for the Pageant in 1980.

Religious responses

Since early in the Ouija board's history, it has been criticized by several Christian groups including Roman Catholics.[4] Catholic Answers, a Christian apologetics organization, states that "The Ouija board is far from harmless, as it is a form of divination (seeking information from supernatural sources)."[32] In 2001, Ouija boards were burned in Alamogordo, New Mexico, by fundamentalist groups alongside Harry Potter books as "symbols of witchcraft."[33][34][35] Religious criticism has also expressed beliefs that the Ouija board reveals information which should only be in God's hands, and thus it is a tool of Satan.[36] A spokesperson for Human Life International described the boards as a portal to talk to spirits and called for Hasbro to be prohibited from marketing them.[37]

Bishops in Micronesia called for the boards to be banned and warned congregations that they were talking to demons and devils when using the boards.[38]

Notable users

- Dick Brooks, of the Houdini Museum in Scranton, Pennsylvania, uses a Ouija board as part of a paranormal and seance presentation.[39]

- Jane Roberts contacted Seth initially through the Ouija board an 'energy personality essence no longer focused in the physical world'. The book Seth Speaks was an explanation of reality by Seth.

- G. K. Chesterton used a Ouija board in his teenage years. Around 1893 he had gone through a crisis of scepticism and depression, and during this period Chesterton experimented with the Ouija board and grew fascinated with the occult.[40]

- Early press releases stated that Vincent Furnier's stage and band name "Alice Cooper" was agreed upon after a session with a Ouija board, during which it was revealed that Furnier was the reincarnation of a 17th-century witch with that name. Alice Cooper later revealed that he just thought of the first name that came to his head while discussing a new band name with his band.[41]

- Poet James Merrill used a Ouija board for years and even encouraged entrance of spirits into his body. Before he died, he recommended that people must not use Ouija boards.[42]

- On the July 25, 2007 edition of the paranormal radio show Coast to Coast AM, host George Noory attempted to carry out a live Ouija board experiment on national radio despite the objections of one of his guests. After recounting a near-death experience in 2000 and noting bizarre events taking place, Noory canceled the experiment.[43]

- Former Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi claimed under oath that, in a séance held in 1978 with other professors at the University of Bologna, the "ghost" of Giorgio La Pira used a Ouija to spell the name of the street where Aldo Moro was being held by the Red Brigades. According to Peter Popham of The Independent: "Everybody here has long believed that Prodi's Ouija board tale was no more than an ill-advised and bizarre way to conceal the identity of his true source, probably a person from Bologna's seething far-left underground whom he was pledged to protect."[44]

- The Mars Volta wrote their album Bedlam in Goliath (2008) based on their alleged experiences with a Ouija board. According to their story (written for them by a fiction author, Jeremy Robert Johnson), Omar Rodriguez Lopez purchased one while traveling in Jerusalem. At first the board provided a story which became the theme for the album. Strange events allegedly related to this activity occurred during the recording of the album: the studio flooded, one of the album's main engineers had a nervous breakdown, equipment began to malfunction, and Cedric Bixler-Zavala's foot was injured. Following these bad experiences the band buried the Ouija board.[45]

- In the murder trial of Joshua Tucker, his mother insisted that he had carried out the murders while possessed by the Devil, who found him when he was using a Ouija board.[46][47]

- Bill Wilson, the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, used a Ouija board and conducted seances in attempts to contact the dead.[48]

- Much of William Butler Yeats's later poetry was inspired, among other facets of occultism, by the Ouija board. Yeats himself did not use it, but his wife did.[49]

- In London in 1994, convicted murderer Stephen Young was granted a retrial after it was learned that four of the jurors had conducted a Ouija board séance and had "contacted" the murdered man, who had named Young as his killer.[50] Young was convicted for a second time at his retrial and jailed for life.[51][52][53]

- Aleister Crowley had great admiration for the use of the ouija board and it played a passing role in his magical workings.[54][55] Jane Wolfe, who lived with Crowley at Abbey of Thelema, also used the Ouija board. She credits some of her greatest spiritual communications to use of this implement. Crowley also discussed the Ouija board with another of his students, and the most ardent of them, Frater Achad (Charles Stansfeld Jones): it is frequently mentioned in their unpublished letters. In 1917 Achad experimented with the board as a means of summoning Angels, as opposed to Elementals. In one letter Crowley told Jones: "Your Ouija board experiment is rather fun. You see how very satisfactory it is, but I believe things improve greatly with practice. I think you should keep to one angel, and make the magical preparations more elaborate." Over the years, both became so fascinated by the board that they discussed marketing their own design. Their discourse culminated in a letter, dated February 21, 1919, in which Crowley tells Jones, "Re: Ouija Board. I offer you the basis of ten percent of my net profit. You are, if you accept this, responsible for the legal protection of the ideas, and the marketing of the copyright designs. I trust that this may be satisfactory to you. I hope to let you have the material in the course of a week." In March, Crowley wrote to Achad to inform him,"I'll think up another name for Ouija." But their business venture never came to fruition and Crowley's new design, along with his name for the board, has not survived. Crowley has stated, of the Ouija Board that,

There is, however, a good way of using this instrument to get what you want, and that is to perform the whole operation in a consecrated circle, so that undesirable aliens cannot interfere with it. You should then employ the proper magical invocation in order to get into your circle just the one spirit you want. It is comparatively easy to do this. A few simple instructions are all that is necessary, and I shall be pleased to give these, free of charge, to any one who cares to apply.[54]

- E. H. Jones and C. W. Hill, whilst prisoners of the Turks during the First World War, used a Ouija board to convince their captors that they were mediums as part of an escape plan.[56]

In popular culture

Ouija boards have figured prominently in various horror films as devices enabling malevolent spirits to spook their users. Most often, they make brief appearances, relying heavily on the atmosphere of mystery the board already holds in the mind of the viewer, in order to add credence to the paranormal presence in the story being told. The Uninvited features a scene with an impromptu board the characters put together; Alison's Birthday has one too, with its claustrophobia-inducing filming; Deadly Messages and Awakenings also feature one. The earliest Western film to hinge its entire plot around the (mis)use of a Ouija board, Witchboard (1986), makes a nod to The Exorcist (where there is a sequence in which a board is used), with a main character called Linda, and her partner quipping "So what you're telling me is... that I'm living with Linda Blair?" Witchboard was so successful it spawned two sequels: Witchboard 2: The Devil's Doorway, and Witchboard III: The Possession. In the same year as the first of the trilogy, the film Spookies also had its own Ouija board scene. What Lies Beneath (2000) also includes a séance scene with a board. Paranormal Activity (2007) involved a violent entity haunting a couple that becomes powerful when the man uses a ouija board, despite the girl's objection. Another 2007 film, Ouija, depicted a group of adolescents whose use of the board causes a murderous spirit to follow them, while four years later, The Ouija Experiment portrayed a group of friends whose use of the board opens, and fails to close, a portal between the worlds of the living and the dead.[57] The 2014 film Ouija featured a group of friends whose use of the board prompted a series of deaths.[58] That film was followed by a 2016 prequel, Ouija: Origin of Evil, which also features the device.

See also

- Ideomotor phenomenon

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

- Penn & Teller: Bullshit!, season 1 episode "Ouija Boards / Near Death Experiences"

Notes

- 1 2 "US Trademark Registration Number 0519636 under First Use in Commerce". tsdr.uspto.gov.

- ↑ Brunvand, Jan Harold (1998). American folklore: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-3350-0.

- 1 2 "The Strange and Mysterious History of the Ouija Board".

- 1 2 3 Raising the devil: Satanism, new religions, and the media. University Press of Kentucky. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

Practically since its invention a century ago, mainstream Christian religions, including Catholicism, have warned against the use of Oujia boards, claiming that they are a means of dabbling with Satanism (Hunt 1985:93-95). Occultists are divided on the Oujia board's value. Jane Roberts (1966) and Gina Covina (1979) express confidence that it is a device for positive transformation and they provide detailed instructions on how to use it to contact spirits and map the other world. But some occultists have echoed Christian warnings, cautioning inexperienced persons away from it.

- ↑ Carlisle, Rodney P. (2 April 2009). Encyclopedia of Play in Today's Society. SAGE Publications. p. 434. ISBN 9781412966702.

In particular, Ouija boards and automatic writing are kin in that they can be practiced and explained both by parties who see them as instruments of psychological discovery; and both are abhorred by some religious groups as gateways to demonic possession, as the abandonment of will and invitation to external forces represents for them an act much like presenting an open wound to a germ-filled environment.

- 1 2 Heap, Michael. (2002). Ideomotor Effect (the Ouija Board Effect). In Michael Shermer. The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience. ABC-CLIO. pp. 127-129. ISBN 1-57607-654-7

- ↑ Adams, Cecil; Ed Zotti (3 July 2000). "How does a Ouija board work?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ↑ Carroll, Robert T. (31 October 2009). "Ouija board". Skeptic's Dictionary. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ↑ French, Chris. (2013). "The unseen force that drives Ouija boards and fake bomb detectors". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ↑ Silvers, Brock. The Taoist Manual (Honolulu: Sacred Mountain Press, 2005), p. 129–132.

- ↑ Chao Wei-pang. 1942. "The origin and Growth of the Fu Chi", Folklore Studies 1:9–27

- 1 2 Orlando, Eugene. "Ancient Ouija Boards: Fact ot Fiction?". Museum of Talking Boards. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ Cornelius, J. E. Aleister Crowley and the Ouija Board, pp. 20–21. Feral House, 2005.

- 1 2 Burgess, Cheryl A; Irving Kirsch; Howard Shane; Kristen L. Niederauer; Steven M. Graham; Alyson Bacon. "Facilitated Communication as an Ideomotor Response". Psychological Science. Blackwell Publishing. 9 (1): 71. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00013. JSTOR 40063250.

- ↑ Gauchou HL; Rensink RA; Fels S. (2012). Expression of nonconscious knowledge via ideomotor actions. Conscious Cogn. 21(2): 976-982.

- ↑ Shenefelt PD. (2011). Ideomotor signaling: from divining spiritual messages to discerning subconscious answers during hypnosis and hypnoanalysis, a historical perspective. Am J Clin Hypn. 53(3): 157-167.

- ↑ Faraday, Michael (1853). "Experimental investigation of table-moving". Journal of the Franklin Institute. 56 (5): 328–333. doi:10.1016/S0016-0032(38)92173-8.

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Table-turning". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Table-turning". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Garrow, Hattie Brown (1 December 2008). "Suffolk's Lakeland High teens find their own answers". The Virginian-Pilot.

- ↑ Dickerson, Brian (6 February 2008). "Crying rape through a Ouija board". Detroit Free Press. McClatchy – Tribune Business News. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Tucker, Milo Asem (Apr 1897). "Comparative Observations on the Involuntary Movements of Adults and Children". The American Journal of Psychology. University of Illinois Press. 8 (3): 402. JSTOR 1411486.

- ↑ Hines, Terence. (2003). Pseudoscience and the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. p. 47. ISBN 1-57392-979-4

- ↑ Robbins, Thomas; Dick Anthony (1979). "The Sociology of Contemporary Religious Movements". Annual Review of Sociology. Annual Reviews. 5: 81–7. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.05.080179.000451. JSTOR 2945948.

- ↑ Howerth, I. W. (Aug 1927). "Science and Religion". The Scientific Monthly. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 25 (2): 151. doi:10.2307/7828. JSTOR 7828.

- ↑ Lloyd, Alfred H. (Sep 1921). "Newspaper Conscience--A Study in Half-Truths". The American Journal of Sociology. The University of Chicago Press. 27 (2): 198–205. doi:10.1086/213304. JSTOR 2764824.

- ↑ White, Stewart Edward (March 1943). The Betty Book. USA: E. P. Dutton & CO., Inc. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0-89804-151-1.

- ↑ "Book Review - Jap Herron". Twainquotes.com. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ ESP Power, by Jane Roberts (2000) (introductory essay by Lynda Dahl). ISBN 0-88391-016-0

- ↑ "All Past National Book Critics Circle Awards Winners and Finalists". National Book Critics Circle. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ "Past winners & finalists by category". The Pulitzer Prizes. Pulitzer.org. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ↑ "National Book Awards – 1979". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ↑ "Are Ouija boards harmless?". Catholic Answers. 1996. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ↑ Ishizuka, Kathy (1 February 2002). "Harry Potter book burning draws fire". School Library Journal. New York. 48 (2): 27.

- ↑ "Book banning spans the globe". Houston Chronicle. 3 October 2002.

- ↑ LaRocca, Lauren (13 July 2007). "The Potter phenomenon". The Frederick News-Post.

- ↑ Zyromski, Page McKean (October 2006). "Facts for Teaching about Halloween". Catechist MAgazine.

- ↑ Smith, Hortense (7 February 2010). "Pink Ouija Board Declared "A Dangerous Spiritual Game," Possibly Destroying Our Children [The Craft]". Jezebel.

- ↑ Dernbach, Katherine Boris (Spring 2005). "Spirits of the Hereafter: Death, Funerary Possession, and the Afterlife in Chuuk, Micronesia". Ethnology. Pittsburgh. 44 (2): 99. doi:10.2307/3773992. JSTOR 3773992.

- ↑ "Psych Theater". psychictheater.com.

- ↑ Chesterton, G.K. (2006). Autobiography. Ignatius Press. p. 77ff. ISBN 1586170716.

- ↑ "Alice Cooper Biography". The Rock Radio.

- ↑ Hunt, Stoker. Ouija: The Most Dangerous Game. Chapter 6, pages 44–50.

- ↑ "Wednesday July 25th, 2007 Coast to Coast AM Show Summary". Coasttocoastam.com. 25 July 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ Popham, Peter (2 December 2005). "The seance that came back to haunt Romano Prodi". The Independent. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ↑ "The Bedlam in Goliath Offers Weird Ouija Tale of The Mars Volta". Alarm Magazine. 2007.

- ↑ Horton, Paula (15 March 2008). "Teen gets 41 years in Benton City slayings". McClatchy – Tribune Business News.

- ↑ Horton, Paula (26 January 2008). "Mom says son influenced by Satan on day of Benton City slayings". McClatchy – Tribune Business News – via Boxden.

- ↑ Raphael, Matthew J. (May 2002). Bill W. and Mr. Wilson: The Legend and Life of A. A.'s Cofounder. Univ of Massachusetts Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-55849-360-5. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ↑ Conradt, Stacy (21 October 2010). "The Quick 10: 10 Famous Uses of the Ouija Board". Mental Floss.

- ↑ Mills, Heather (25 October 1994). "Retrial order in 'Ouija case'". The Independent. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ Spencer, J.R. (November 1995). "Seances, and the Secrecy of the Jury–Room". The Cambridge Law Journal. 54 (3): 519–522. doi:10.1017/S0008197300097282. JSTOR 4508123.

- ↑ "Jury deliberations may be studied". BBC News. 22 January 2005. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ "'Ouija board' appeal dismissed". BBC News. 7 December 2004. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- 1 2 Cornelious, J. Edward Aleister Crowley and the Ouija Board 2005 ISBN 978-1-932595-10-9

- ↑ Mini site J. Edward's book, Aleister Crowley and the Ouija Board

- ↑ "Jones, Elias Henry". National Library of Wales Welsh Biography Online.

- ↑ "THE OUIJA EXPERIMENT". PHASE 4 FILMS. Phase 4 Films Inc. n.d. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ↑ "The Ouija Experiment (2014)". Rotten Tomatoes.

TM, SM

References

- Cain, D. Lynn, "OUIJA – For the Record" 2009 ISBN 978-0-557-15871-3

- Carpenter, W.B., "On the Influence of Suggestion in Modifying and directing Muscular Movement, independently of Volition", Royal Institution of Great Britain, (Proceedings), 1852, (12 March 1852), pp. 147–153.

- Cornelius, J. Edward, Aleister Crowley and the Ouija Board. Feral House, 2005. ISBN 1-932595-10-4

- Gruss, Edmond C., The Ouija Board: A Doorway to the Occult 1994 ISBN 0-87552-247-5

- Hunt, Stoker, Ouija: The Most Dangerous Game. 1992 ISBN 0-06-092350-4

- Hill, Joe, Heart-Shaped Box

- Murch, R., "A Brief History of the Ouija Board", Fortean Times, No.249, (June 2009), pp. 32–33.

- Schneck, R.D., "Ouija Madness", Fortean Times, No.249, (June 2009), pp. 30–37.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ouija. |

- Information on talking boards

- Skeptics

- Ouija board helps psychologists probe the subconscious from New Scientist

- The Skeptics' Dictionary: Ouija

- An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural

- How does a Ouija board work? from The Straight Dope

- Do Ouija Boards Work - The Fact and Fiction

- Trade marks and patents

- Trade-Mark Registration: "Ouija" (Trademark no. 18,919; 3 February 1891: Kennard Novelty Company)

- "Ouija or Egyptian Luck Board" (patent no.446,054; 10 February 1891: Elijah J. Bond – assigned to Charles W. Kennard and William H. A. Maupin)

- "Talking-Board" (patent no.462,819; 10 November 1891: Charles W. Kennard)

- "Game Apparatus" (patent no. 479,266: 19 July 1892: William Fuld)

- "Game Apparatus" (patent no. 619,236: 7 February 1899: Justin F. Simonds)

- "Ouija or Talking Board" (patent no.1,125,833; 19 January 1915: William Fuld)

- "Design for the Movable Member of a Talking-Board" (patent no.D56,001; 10 August 1920: William Fuld)

- "Design of Finger-Rest and Pointer for a Game" (patent no. D56,085; 10 August 1920: John Vanderkamp – assigned to Goldsmith Publishing Company)

- "Message Interpreting Device" or "Psychic Messenger" (patent no.1,352,046; 7 September 1920: Frederick H. Black)

- "Design for the Movable Member of a Talking-Board" (patent no.D56,001; 10 August 1920: William Fuld)

- "Ouija Board" (patent no.D56,449; 26 October 1920: Clifford H. McGlasson)

- "Psychic Game" (patent no.1,370,249; 1 March 1921: Theodore H. White)

- "Ouija Board" (patent no.1,400,791; 20 December 1921: Harry M. Bigelow)

- "Game Board" (patent no.1,422,042; 4 July 1922: John R. Donnelly)

- "(Magnetic) Toy" (patent no.1,422,775; 11 July 1922: Leon Martocci-Pisculli)

- "Psychic Instrument" (patent no.1,476,158; 4 December 1923: Grover C. Haffner)

- "Game" (patent no.1,514,260; 4 November 1924: Alfred A. Rees)

- "Amusement Device" (patent no.1,870,677; 9 August 1932: William A. Fuld)

- "Amusement Device" (patent no.2,220,455; 5 November 1940: John P. McCarthy)

- "Finger Pressure Actuated Message Interpreting Amusement Device" (patent no.2,511,377; 13 June 1950: Raymond S. Richmond)

- "Message Device With Freely Swingable Pointer" (patent no.3,306,617; 28 February 1967: Thomas W. Gillespie)

- Other

- "'Ouija board' appeal (against second guilty verdict) dismissed" – R. v. Young (1995)

- BBC video on Ouija Board

- Ouija at DMOZ