Pantograph (transport)

A pantograph (or "pan") is an apparatus mounted on the roof of an electric train, tram or electric bus[1] to collect power through contact with an overhead catenary wire. It is a common type of current collector. Typically, a single wire is used, with the return current running through the track. The term stems from the resemblance of some styles to the mechanical pantographs used for copying handwriting and drawings.

Invention

The pantograph was invented in 1879 by Walter Reichel, chief engineer at Siemens & Halske in Germany.[2] A flat slide-pantograph was invented in 1895 at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad[3]

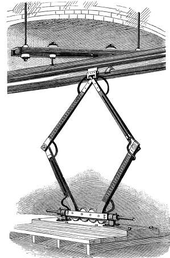

The familiar diamond-shaped roller pantograph was invented by John Q. Brown of the Key System shops for their commuter trains which ran between San Francisco and the East Bay section of the San Francisco Bay Area in California.[4][5] They appear in photographs of the first day of service, 26 October 1903.[6] For many decades thereafter, the same diamond shape was used by electric-rail systems around the world and remains in use by some today.

The pantograph was an improvement on the simple trolley pole, which prevailed up to that time, primarily because the pantograph allows an electric-rail vehicle to travel at much higher speeds without losing contact with the overhead lines.

Modern use

The most common type of pantograph today is the so-called half-pantograph (sometimes 'Z'-shaped), which has evolved to provide a more compact and responsive single-arm design at high speeds as trains get faster. Louis Faiveley invented this type of pantograph in 1955.[7] The half-pantograph can be seen in use on everything from very fast trains (such as the TGV) to low-speed urban tram systems. The design operates with equal efficiency in either direction of motion, as demonstrated by the Swiss and Austrian railways whose newest high performance locomotives, the Re 460 and Taurus, operate with them set in opposite direction.

Technical details

The electric transmission system for modern electric rail systems consists of an upper, weight-carrying wire (known as a catenary) from which is suspended a contact wire. The pantograph is spring-loaded and pushes a contact shoe up against the underside of the contact wire to draw the current needed to run the train. The steel rails of the tracks act as the electrical return. As the train moves, the contact shoe slides along the wire and can set up standing waves in the wires which break the contact and degrade current collection. This means that on some systems adjacent pantographs are not permitted.

Pantographs are the successor technology to trolley poles, which were widely used on early streetcar systems. Trolley poles are still used by trolleybuses, whose freedom of movement and need for a two-wire circuit makes pantographs impractical, and some streetcar networks, such as the Toronto streetcar system, which have frequent turns sharp enough to require additional freedom of movement in their current collection to ensure unbroken contact. However, many of these networks, including Toronto's, are undergoing upgrades to accommodate pantograph operation.

Pantographs with overhead wires are now the dominant form of current collection for modern electric trains because, although more fragile than a third-rail system, they allow the use of higher voltages.

Pantographs are typically operated by compressed air from the vehicle's braking system, either to raise the unit and hold it against the conductor or, when springs are used to effect the extension, to lower it. As a precaution against loss of pressure in the second case, the arm is held in the down position by a catch. For high-voltage systems, the same air supply is used to "blow out" the electric arc when roof-mounted circuit breakers are used.[8][9]

Single- and double-arm pantographs

Pantographs may have either a single or a double arm. Double-arm pantographs are usually heavier, requiring more power to raise and lower, but may also be more fault-tolerant.

On railways of the former USSR, the most widely used pantographs are those with a double arm ("made of two rhombs"), but since the late 1990s there have been some single-arm pantographs on Russian railways. Some streetcars use double-arm pantographs, among them the Russian KTM-5, KTM-8, LVS-86 and many other Russian-made trams, as well as some Euro-PCC trams in Belgium. American streetcars use either trolley poles or single-arm pantographs.

Metro systems and overhead lines

Most rapid transit systems are powered by a third rail, but some use pantographs, particularly ones that involve extensive above-ground running. Hybrid metro-tram or 'pre-metro' lines whose routes include tracks on city streets or in other publicly accessible areas, such as the MBTA Green Line, naturally must use overhead wire, since a third rail would normally obstruct street traffic and present too great a risk of electrocution.

Among the various exceptions are several tram systems, such as the ones in Bordeaux, Angers, Reims and Dubai that use a proprietary underground system developed by Alstom, called APS, which only applies power to segments of track that are completely covered by the tram. This system was originally designed to be used in the historic centre of Bordeaux because an overhead wire system would cause a visual intrusion. Similar systems that avoid overhead lines have been developed by Bombardier, AnsaldoBreda, CAF, and others. These may consist of physical ground-level infrastructure, or use energy stored in battery packs to travel over short distances without overhead wiring.

Overhead pantographs are sometimes used as alternatives to third rails because third rails can ice over in certain winter weather conditions. The MBTA Blue Line uses pantograph power for all of its surface route. The entire Metro systems of Madrid, Barcelona, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Seoul and Delhi use overhead wiring and pantographs. Pantographs were also used on the Nord-Sud Company rapid transit lines in Paris until the other operating company of the time, Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris bought out the company and replaced all overhead wiring with the standard third rail system used on other lines.

The Chicago Transit Authority's Yellow Line used both third rail and pantograph collection, switching from the former to the latter at roughly halfway from Howard station towards the terminus at Dempster–Skokie station and vice versa. The overhead portion was a remnant of the Chicago North Shore and Milwaukee Railroad's high-speed Skokie Valley Route,[10] and was the only line on the entire Chicago subway system to utilize pantograph collection for any length. As such, the line required railcars that featured pantographs as well as third rail shoes, and since the overhead was a very small portion of the system, only a few cars would be so equipped. The changeover occurred at the grade crossing at East Prairie, the former site of the Crawford-East Prairie station. Here, trains bound for Dempster-Skokie would raise their pantographs, while those bound for Howard would lower theirs, doing so at speed in both instances. In 2005, due to the cost and unique maintenance needs for what only represents a very small portion of the system, the overhead system was removed and replaced with the same third rail power as that used throughout the system, which allows all of Chicago's railcars to operate on the line, and the pantographs removed from the Skokie equipped cars.

Until 2010 the Oslo Metro line 1 changed from third rail to overhead line power at Frøen station. Due to the many level crossings, it was deemed difficult to install a third rail on the rest of the older line's single track.[11] After 2010 third rails are used in spite of level crossings. The third rails have gaps, but there are two contact shoes.

Weaknesses

Contact between pantograph and overhead catenary wire is usually assured through a block of graphite. This material conducts electricity while working as a lubricant. As graphite is brittle, pieces can break off during operation. Bad pantographs can seize the overhead wire and tear it down. So there is a two way influence where bad wires can damage the pantograph and bad pantographs can damage the wires. To prevent this, a pantograph monitoring station can be used.

In the UK, in older vehicles the pantographs are raised by air pressure, and the graphite contact strips cover some vents in the pantograph head which release the air if a graphite strip is lost, automatically lowering the pantograph to prevent damage. Newer electric traction units may use more sophisticated methods involving microprocessors which detect the disturbances caused by arcing at the point of contact if the graphite strips are damaged. There are always at least two pantographs so the other one can be used if one is damaged.

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pantograph. |

- ↑ Urbino bus with pantograph

- ↑ A Century of Traction. Electrical Inspections, page 7, by Basil Silcove

- ↑ "A ninety-six ton electric locomotive". Scientific American. New York. 10 August 1895.

- ↑ U.S. Patent No. 764224 issued July 5, 1904

- ↑ Sappers, Vernon (2007). Key System Streetcars. Signature Press. p. 369.

- ↑ Walter Rice and Emiliano Echeverria (2007). The Key System: San Francisco and the Eastshore Empire. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 13, 16.

- ↑ Louis Faiveley, Current Collecting Device, US 2935576, granted May 3, 1960.

- ↑ Hammond, Rolt (1968). "Development of electric traction". Modern Methods of Railway Operation. London: Frederick Muller. pp. 71–73. OCLC 467723.

- ↑ Ransome-Wallis, Patrick (1959). "Electric motive power". Illustrated Encyclopedia of World Railway Locomotives. London: Hutchinson. p. 173. ISBN 0-486-41247-4. OCLC 2683266.

- ↑ Garfield, Graham. "Yellow Line". Chicago "L".org. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WYleLB87g_o&NR=1