Parsley massacre

| Parsley massacre | |

|---|---|

| Location | Dominican Republic |

| Date |

2 October 1937 – 8 October 1937 |

| Target | Haitian population |

Attack type | Genocide, massacre, mass murder, ethnic cleansing |

| Deaths | 537–12,166 |

| Perpetrators | Dominican Republic government led by President Rafael Trujillo |

.svg.png)

The Parsley massacre, also referred to as El Corte (the cutting) in Spanish[1] and as Kout kouto a (the knife blow) in Creole, was a genocidal massacre carried out in fall of 1937 against the Haitian population living in the borderlands of the Dominican Republic with Haiti at the direct order of Dominican President Rafael Trujillo. Estimates of the total number of deaths vary considerably and range from a low of 547 to a high of 12,166 (see table below).[2][3][4]

Origin of the name

The popular name[5] for the massacre came from the shibboleth that the dictatorial Trujillo had his soldiers apply to determine whether or not those living on the border were native Afro-Dominicans or immigrant Afro-Haitians. Dominican soldiers would hold up a sprig of parsley to someone and ask what it was. How the person pronounced the Spanish word for parsley (perejil) determined their fate. The Haitian languages, French and Haitian Creole, pronounce the r as a uvular approximant or a voiced velar fricative, respectively so their speakers can have difficulty pronouncing the alveolar tap or the alveolar trill of Spanish, the language of the Dominican Republic. Also, only Spanish but not French or Haitian Creole pronounces the j as the voiceless velar fricative. If they could pronounce it the Spanish way the soldiers considered them Dominican and let them live, but if they pronounced it the French or Creole way they considered them Haitian and executed them.

The term Parsley Massacre was used frequently in the English-speaking media 75 years after the event, but most scholars recognize that it is a misconception, as research by Lauren Derby shows that the explanation is based more on myth than on personal accounts.[6]

Events

Rafael Trujillo, a proponent of anti-Haitianism, made his intentions towards the Haitian community clear in a short speech he gave 2 October 1937 at a dance in his honor in Dajabón. He said,

For some months, I have traveled and traversed the border in every sense of the word. I have seen, investigated, and inquired about the needs of the population. To the Dominicans who were complaining of the depredations by Haitians living among them, thefts of cattle, provisions, fruits, etc., and were thus prevented from enjoying in peace the products of their labor, I have responded, 'I will fix this.' And we have already begun to remedy the situation. Three hundred Haitians are now dead in Bánica. This remedy will continue.[7]

Trujillo reportedly was acting in response to reports of Haitians stealing cattle and crops from Dominican borderland residents. According to some sources, the massacre killed an estimated 20,000 Haitians[8][9] living in the Dominican border—clearly at Trujillo's direct order. However, as shown in the table below and mentioned above, estimates of the number of victims vary widely. For approximately five days, from 2 October 1937 to 8 October 1937, Dominican troops killed Haitians with guns, machetes, clubs, and knives. Some died while trying to flee to Haiti across the Artibonite River, which has often been the site of bloody conflict between the two nations.[10]

Lauren Derby claims that a majority of those who died were born in the Dominican Republic and belonged to well-established Haitian communities in the borderlands.[11] However, it is difficult for anyone to ascertain a victim's place of birth, especially considering that, in most cases, their identities are unknown, and their births may not have been officially recorded. Furthermore, Haiti has historically awarded citizenship by Jus sanguinis, making anyone with a Haitian parent a Haitian citizen, whereas from as early as 1929 until 2014, the Dominican Republic followed a restricted Jus soli citizenship policy, which excluded from this privilege illegal residents and anyone not having legal permanent residency status.[12][13]

Contributing factors

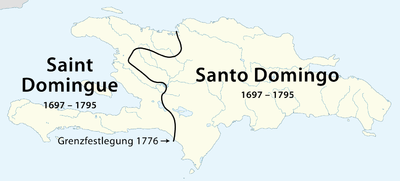

The Dominican Republic, formerly the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo, is the eastern portion of the island of Hispaniola and occupies five-eighths of the land while having ten million inhabitants.[14] In contrast, Haiti, the former French colony of Saint-Domingue, is on the western three-eighths of the island[15][16] and has almost exactly the same population, with an estimated 500 people per square mile.[17]

This has forced many Haitians onto land too mountainous, eroded, or dry for productive farming. Instead of staying on lands incapable of supporting them, many Haitians migrated to Dominican soil, where land hunger was low. While Haitians benefited by gaining farm land, Dominicans in the borderlands subsisted mostly on agriculture, and benefited from the ease of exchange of goods with Haitian markets.

Due to inadequate roadways connecting the borderlands to major cities, "Communication with Dominican markets was so limited that the small commercial surplus of the frontier slowly moved toward Haiti."[18] This threatened Trujillo's regime because of long-standing border disputes between the two nations. If large numbers of Haitian immigrants began to occupy the less densely populated Dominican borderlands, the Haitian government might try to make a case for claiming Dominican land. Additionally, loose borders let contraband pass freely, and without taxes between nations, depriving the Dominican Republic of tariff revenue.

Furthermore, the Dominican government saw the loose borderlands as a liability in terms of possible formation of revolutionary groups that could flee across the border with ease, while at the same time amassing weapons and followers.[19]

Repercussions

Despite attempts to blame Dominican civilians, it has been confirmed by U.S. sources that "bullets from Krag rifles were found in Haitian bodies, and only Dominican soldiers had access to this type of rifle."[20] Therefore, the Haitian Massacre, which is still referred to as el corte (the cutting) by Dominicans and as kouto-a (the knife) by Haitians, was, "...a calculated action on the part of Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo to homogenize the furthest stretches of the country in order to bring the region into the social, political and economic fold,"[10] and rid his republic of Haitians.

Thereafter, Trujillo began to develop the borderlands to link them more closely with urban areas.[21] These areas were modernized, with the addition of modern hospitals, schools, political headquarters, military barracks, and housing projects—as well as a highway to connect the borderlands to major cities.

Additionally, after 1937, quotas restricted the number of Haitians permitted to enter the Dominican Republic, and a strict and often discriminatory border policy was enacted. Dominicans continued to deport and kill Haitians in southern frontier regions—as refugees died of exposure, malaria and influenza.[22]

In the end, U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt and Haitian president Sténio Vincent sought reparations of $750,000, of which the Dominican government paid $525,000 (US$ 8,656,423.61 in 2016 dollars). Of this 30 dollars per victim, survivors received only 2 cents each, due to corruption in the Haitian bureaucracy.[23]

Controversy

Despite the number of reported deaths by Haitian, American and British officials, and following over half a century of agricultural expansion and population growth which may have led to accidental unearthing of human remains, no mass grave containing the bodies of murdered Haitians has ever been found.[24]

Nonetheless, the lack of graves does not prove that the killings did not take place; however, it does suggest that the number of dead was in reality much less than those commonly reported. Reports from the day have numbers ranging from as little as 1,000 dead up to 12,000;[24] even the upper end of the scale is dwarfed by the 30,000 victims which are commonly reported in the present. This inflation of the tally is attributed by some to the propaganda of anti-Trujillo exiles who wanted to rally international support against the dictator Trujillo.

On the Dominican side, there are no known formally documented first-hand witness accounts by military personnel carrying out the executions nor from civilians. Historian and former Dominican ambassador to the United States Bernardo Vega has cited that not many weeks after the end of the alleged massacre, Haitians were once again lining up for work at Dominican sugar cane plantations, something he considers as strange as "lambs willingly walking into the slaughterhouse."[25]

Conflicting reports on the number of victims

Dominican historian Bernardo Vega has chronologically tabulated many conflicting reports on the number of victims, by various sources, with none of the estimates showing the exaggerated 20,000–30,000 figures.[24] The earliest report, dated 11 October 1937, by the United States consul in Cap-Haïtien, puts the number at "almost one thousand". On 6 November 1937 an official diplomatic note from the Haitian to the Dominican government speaks of 2,040. By 19 December, a Haitian minister in Washington gave the number 12,168. On the first of January 1938, the Dominican foreign minister Julio Ortega Frier offered the figure of 547. See other reports below.

| Date | Source | Number |

|---|---|---|

| 11 October 1937 | United States consul in Cap-Haïtien | almost 1,000 |

| 25 October 1937 | Haitian diplomatic mission in Santo Domingo | about 5,000 |

| 30 October 1937 | British Minister in Port-au-Prince | 5,000 |

| 6 November 1937 | List of names prepared by Ouanaminthe priest | 1,093 |

| 6 November 1937 | Diplomatic note from the Haitian to the Dominican government | 2,040 |

| 9 November 1937 | Haitian Foreign Minister in Washington, DC | at least 3,000 |

| 9 November 1937 | Public statement by the United States Secretary of State | several thousands |

| 10 November 1937 | Haitian Foreign Minister to British Minister in Port-au-Prince | 4,000 to 5,000 |

| 13 November 1937 | Haitian Foreign Minister in Washington, DC | about 5,000 |

| 25 November 1937 | Haitian President speaking to journalist | at least 8,000 |

| 10 December 1937 | Haitian government's official statement | about 7,000 |

| 12 December 1937 | Haitian Bishop in public letter | about 3,000 |

| 12 December 1937 | Haitian President in letter to three Latin American presidents | thousands |

| 19 December 1937 | Haitian Foreign Minister in Washington, DC | 12,166 |

| 1 January 1938 | Dominican Foreign Minister in Santo Domingo | 547 |

| Sep. 1938 | United States diplomatic mission in Santo Domingo | about 5,000 |

In popular culture

- Edwidge Danticat's novel The Farming of Bones chronicles the Haitians' escape from the Dominican Republic following the massacre and the spread of antihaitianismo. Edwidge Danticat's short story "Nineteen Thirty-Seven", from Krik? Krak! also refers to the Massacre River as a site that divides Haiti from the Dominican Republic, and where the protagonist's grandmother is killed.[26]

- Rita Dove drew inspiration from the massacre for her poem "Parsley".[27]

- The massacre, along with many other incidents of the Trujillo era, is discussed in the book The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Dominican-American author Junot Díaz.

- A fictional Haitian woman named Chucha is discussed as having escaped from this massacre in the book How The Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents by Julia Alvarez.

- In the novel Massacre River, Haitian author René Philoctète tells the story of the massacre through his narrative of a Dominican man trying to save his Haitian wife.[28]

- The massacre is a focus of Jacques Stephen Alexis' 1955 novel General Sun, My Brother.

- The Parsley Massacre is chronicled in the novel El masacre se pasa a pié (The massacre crossed on foot) by Dominican author Freddy Prestol Castillo.

- In Roxane Gay's short fiction, "In the Manner of Water or Light", a woman reveals to her daughter and granddaughter how she became pregnant with her only child in the Dajabón River during the Parsley Massacre.

- When Mario Vargas Llosa's novel The Feast of the Goat, mentions 'What do five, ten, twenty thousand Haitians matter when it's a matter of saving an entire people', it refers to the justification of the 1937 ethnic cleansing Parsley Massacre of all Haitians in the Dominican Republic border area.

See also

- 1804 Haiti massacre

- History of Haiti

- History of the Dominican Republic

- List of massacres in the Dominican Republic

- List of massacres in Haiti

References

- ↑ Wucker, Michele. "The River Massacre: The Real and Imagined Borders of Hispaniola". Windows on Haiti. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Crassweller mentions those estimates and adds that "a figure of 15,000 to 20,000 would be reasonable, but this is guesswork". Robert D. Crasweller, The Life and Times of a Caribbean Dictator, New York, The Macmillan Company, 1966, p. 156.

- ↑ Lauro Capdevila, La dictature de Trujillo : République dominicaine, 1930–1961, Paris, L'Harmattan, 1998

- ↑ Roorda mentions 12,000 as a likely figure. Eric Paul Roorda, "Genocide Next Door: The Good Neighbor Policy, the Trujillo Regime, and the Haitian Massacre of 1937" in Diplomatic History, Vol 20, Issue 3, July 1996, p. 301.

- ↑ The name used by historians and scholars is Haitian massacre of 1937. The expression "Parsley Massacre" appears nowhere in works published by Trujillo Era scholars such as Jésus de Galindez (1956), Robert D. Crassweller (1966), Eric Paul Roorda (1996), Lauro Capdevila (1998) and Lauren Derby (2009).

- ↑ "Hispaniola: Trujillo's Voudou Legacy".

- ↑ Turtis, Richard Lee (2002). "A World Destroyed, A Nation Imposed: The 1937 Haitian Massacre in the Dominican Republic". Hispanic American Historical Review. 82 (3): 589–635 [p. 613]. doi:10.1215/00182168-82-3-589.

- ↑ pg 78 – Robert Pack (editor), Jay Parini (Editor). Introspections. PUB. p. 2222.

On 2 October 1937, Trujillo had ordered 10,000 Haitian cane workers executed because they could not roll the "R" in perejil the Spanish word for parsley. - ↑ Cambeira, Alan. Quisqueya la bella (1996 ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 182. ISBN 1-56324-936-7.

anyone of African descent found incapable of pronouncing correctly, that is, to the complete satisfaction of the sadistic examiners, became a condemned individual. This holocaust is recorded as having a death toll reaching thirty thousand innocent souls, Haitians as well as Dominicans. - 1 2 Turtis, 590.

- ↑ Derby, Lauren (1994). "Haitians, Magic, and Money: Raza and Society in the Haitian-Dominican Borderlands, 1900 to 1937". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 36 (3): 508. doi:10.1017/S0010417500019216.on line copy Derby explains: "This point is important because, by the Dominican constitution, all those born on Dominican soil are Dominican. If this population was primarily migrants, then they were Haitians, thus making it easier to justify their slaughter. However, our findings indicate that they were legally Dominicans, even if culturally defined as Haitians since they were of Haitian origin." (Derby, p.508)

- ↑ Tribunal Constitucional. "Sentencia TC/0168/13" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Virgilio. "Erroneous objections to the Dominican constitutional ruling on citizenship". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ Augelli, John P. (1980). "Nationalization of Dominican Borderlands". Geographical Review. 70 (1): 21. doi:10.2307/214365. JSTOR 214365.

- ↑ "Hispaniola Article". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ↑ "Dominican Republic 2014". Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Augelli, 21.

- ↑ Augelli, 24.

- ↑ Turtis, 600.

- ↑ Peguero, Valentina (2004). The Militarization of Culture in the Dominican Republic: From the Captains General to General Trujillo. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 114. ISBN 0803204345.

- ↑ Turtis, 623.

- ↑ Roorda, Eric Paul (1998). The Dictator Next Door: The Good Neighbor Policy and the Trujillo Regime in the Dominican Republic, 1930–1945. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 132. ISBN 082232234X.

- ↑ p.41 – Bell, Madison Smartt (17 July 2008). "A Hidden Haitian World". New York Review of Books. 55 (12).

- 1 2 3 Vega, Bernardo. "La matanza de 1937" (in Spanish). lalupa.com.do. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ "desde la redacción: GENOCIDIO HAITIANO". alfonseca2000.blogspot.hu. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- ↑ Danticat, Edwidge. Krik? Krak!, New York: Soho Press, 1995

- ↑ Rita Dove, "Parsley" from Museum (Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University Press, 1983).

- ↑ "Massacre River by René Philoctète – Reviews, Discussion, Bookclubs, Lists". goodreads.com. Retrieved 2014-01-25.