Pazyryk burials

Coordinates: 49°34′44″N 88°09′11″E / 49.579°N 88.153°E

The Pazyryk (Russian: Пазырык) burials are a number of Scythian[1][2][3] Iron Age tombs found in the Pazyryk Valley of the Ukok plateau in the Altai Mountains, Siberia, south of the modern city of Novosibirsk, Russia; the site is close to the borders with China, Kazakhstan and Mongolia.[4] Numerous comparable burials have been found in neighboring western Mongolia.

The tombs are Scythian-type kurgans, barrow-like tomb mounds containing wooden chambers covered over by large cairns of boulders and stones, dated to the 4th - 3rd centuries BCE.[5] The spectacular burials at Pazyryk are responsible for the introduction of the term kurgan, a Russian word of Turkic origin, into general usage to describe these tombs. The region of the Pazyryk kurgans is considered the type site of the wider Pazyryk culture. The site is included in the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site.[6]

The bearers of the Pazyryk culture were horse-riding pastoral nomads of the steppe, and some may have accumulated great wealth through horse trading with merchants in Persia, India and China.[7] This wealth is evident in the wide array of finds from the Pazyryk tombs, which include many rare examples of organic objects such as felt hangings, Chinese silk, the earliest known pile carpet, horses decked out in elaborate trappings, and wooden furniture and other household goods. These finds were preserved when water seeped into the tombs in antiquity and froze, encasing the burial goods in ice, which remained frozen in the permafrost until the time of their excavation.

"At Pazyryk too are found bearded mascarons (masks) of well-defined Greco-Roman origin, which were doubtless inspired by the Hellenistic kingdoms of the Cimmerian Bosporus."[8]

Discoveries

The first tomb at Pazyryk, barrow 1, was excavated by the archaeologist M. P. Gryaznov in 1929; barrows 2-5 were excavated by Sergei Ivanovich Rudenko in 1947-1949.[9] While many of the tombs had already been looted in earlier times, the excavators unearthed buried horses, and with them immaculately preserved cloth saddles, felt and woven rugs including the world's oldest pile carpet,[10][11] a 3-metre-high four-wheel funeral chariot from the 5th century BC and other splendid objects that had escaped the ravages of time.[12] These finds are now exhibited at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

Craniological studies of samples from the Pazyryk burials determined that skulls were generally of Europoid type, with some showing Mongoloid features.[13]

Pazyryk chief

Rudenko's most striking discovery was the body of a tattooed Pazyryk chief: a thick-set, powerfully built man who had died when he was about 50. Parts of the body had deteriorated, but much of the tattooing was still clearly visible (see image). Subsequent investigation using reflected infrared photography revealed that all five bodies discovered in the Pazyryk kurgans were tattooed.[14] No instruments specifically designed for tattooing were found, but the Pazyryks had extremely fine needles with which they did miniature embroidery, and these were probably used for tattooing.

The chief was elaborately decorated with an interlocking series of striking designs representing a variety of fantastic beasts. The best preserved tattoos were images of a donkey, a mountain ram, two highly stylized deer with long antlers and an imaginary carnivore on the right arm. Two monsters resembling griffins decorate the chest, and on the left arm are three partially obliterated images which seem to represent two deer and a mountain goat. On the front of the right leg a fish extends from the foot to the knee. A monster crawls over the right foot, and on the inside of the shin is a series of four running rams which touch each other to form a single design. The left leg also bears tattoos, but these designs could not be clearly distinguished. In addition, the chief's back is tattooed with a series of small circles in line with the vertebral column. This tattooing was probably done for therapeutic reasons. Contemporary Siberian tribesmen still practice tattooing of this kind to relieve back pain.

Ice Maiden

The most famous undisturbed Pazyryk burial so far recovered is the Ice Maiden or "Altai Lady" found by archaeologist Natalia Polosmak in 1993 at Ukok, near the Chinese border. The find was a rare example of a single woman given a full ceremonial burial in a wooden chamber tomb in the fifth century BC, accompanied by six horses.[4] She had been buried over 2,400 years ago in a casket fashioned from the hollowed-out trunk of a Siberian larch tree. On the outside of the casket were stylized images of deer and snow leopards carved in leather. Shortly after burial the grave had apparently been flooded by freezing rain, and the entire contents of the burial chamber had remained frozen in permafrost. Six horses wearing elaborate harnesses had been sacrificed and lay to the north of the chamber.[15] The maiden's well-preserved body, carefully embalmed with peat and bark, was arranged to lie on her side as if asleep. She was young, and her hair was shaven off but wearing a wig and tall hat; she had been 167 cm (5 feet 6 inches) tall. Even the animal style tattoos were preserved on her pale skin: creatures with horns that develop into flowered forms. Her coffin was made large enough to accommodate the high felt headdress she was wearing, which was decorated with swans and gold-covered carved cats.[16] She was clad in a long crimson and white striped woolen skirt and white felt stockings. Her yellow blouse was originally thought to be made of wild "tussah" silk but closer examination of the fibers indicate the material is not Chinese but was a wild silk which came from somewhere else, perhaps India.[7] Near her coffin was a vessel made of yak horn, and dishes containing gifts of coriander seeds: all of which suggest that the Pazyryk trade routes stretched across vast areas of Iran. Similar dishes in other tombs were thought to have held Cannabis sativa, confirming a practice described by Herodotus[4] but after tests the mixture was found to be coriander seeds, probably used to disguise the smell of the body.

Two years after the discovery of the "Ice Maiden" Dr. Polosmak's husband, Vyacheslav Molodin, found a frozen man, elaborately tattooed with an elk, with two long braids that reached to his waist, buried with his weapons.

Doctor Anicua also noted that her blouse was a bit stained, indicating that the material was not a new garment, made for the burial.

Pazyryk carpet

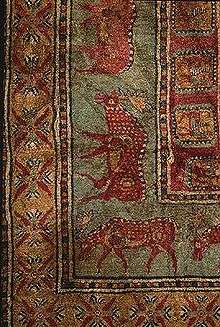

One of the most famous finds at Pazyryk is the Pazyryk carpet, which is probably the oldest surviving carpet in the world. It measures 183×200 cm and has a knot density of approximately 360 000 knots per square meter, which is a higher knot density than most modern carpets. The middle of the carpet consists of a ribbon motif, while in the border there is a procession with deers and in another border warriors on horses. The Pazyryk carpet was probably manufactured in Armenia or Persia around 400 B.C. When it was found it had been deeply frozen in a block of ice, which is why it is so well-preserved. The carpet can be seen at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia.[17]

Other findings

In a corner of one grave chamber of the Pazyryk cemetery was a fur bag containing cannabis seed, a censer filled with stones, and the hexapod frame of an inhalation tent - these are believed to have been utilized at the end of the funerary ritual for purification.

Other undisturbed kurgans have been found to contain remarkably well-preserved remains, comparable to the earlier Tarim mummies of Xinjiang. Bodies were preserved using mummification techniques and were also naturally frozen in solid ice from water seeping into the tombs. They were encased in coffins made from hollowed trunks of larch (which may have had sacral significance) and sometimes accompanied by sacrificed concubines and horses. The clustering of tombs in a single area implies that it had particular ritual significance for these people, who were likely to have been willing to transport their deceased leaders great distances for burial.

As recently as the summer of 2012, tombs have been discovered at various locations. In January 2007 a timber tomb of a blond chieftain warrior was unearthed in the permafrost of the Altai mountains region close to the Mongolian border.[18] The body of the presumed Pazyryk chieftain is tattooed; his sable coat is well preserved, as are some other objects, including what looks like scissors. A local archaeologist, Aleksei Tishkin, complained that the indigenous population of the region strongly disapproves of archaeological digs, prompting the scientists to move their activities across the border to Mongolia.[19]

Pazyryk culture

Rudenko initially assigned the neutral label Pazyryk culture for these nomads and dated them to the 5th century BC; the dating has been revised for barrows 1-5 at Pazyryk, which are now considered to date to the 4th-3rd centuries B.C.[20] The Pazyryk culture has since been connected to the Scythians whose similar tombs have been found across the steppes. The Siberian animal style tattooing is characteristic of the Scythians. Trading routes between Central Asia, China and the Near East passed through the oases on the plateau and these ancient Altai nomads profited from the rich trade and culture passing through.[21] There is evidence that Pazyryk trade routes were vast and connected with large areas of Asia including India, perhaps Pazyryk merchants largely trading in high quality horses.[4]

It has been suggested that Pazyryk was a homeland for these tribes before they migrated west. There is also the possibility that the current inhabitants of the Altai region are descendants of the Pazyryk culture, a continuity that would accord with current ethnic politics: Archaeogenetics is now being used to study the Pazyryk mummies.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ "Pazyryk". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Scythian Art". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Drug cult: History of drug use in religion". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Ice Mummies: Siberian Ice Maiden". PBS - NOVA. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ↑ A Special Issue on the Dating of Pazyryk. Source: Notes in the History of Art 10, no. 4, p. 4.

- ↑ "Golden Mountains of Altai". UNESCO. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- 1 2 Bahn, Paul G. (2000). The Atlas of World Geology. New York: Checkmark Books. p. 128. ISBN 0-8160-4051-6.

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ Rudenko 1970, pp. 18, 33

- ↑ "Rug and carpet: Oriental carpets". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Central Asian Arts: Altaic tribes". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Stone Age: European cultures". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ↑ Rudenko 1970, p. 45 "Although in general the skulls in the series are of europeoid type, there are some among them with markedly mongoloid features."

- ↑ Findings published in Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, Spring 2005.

- ↑ Polosmak, Natalia (1994). "A Mummy Unearthed from the Pastures of Heaven." National Geographic 186:4, p. 91.

- ↑ Polosmak (1994), pp. 98-99.

- ↑ "History of handknotted carpets". CarpetEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Russian Archaeologists Discover Remains of Ancient Chieftain in Altai Permafrost". 2007-01-10. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ↑ Daria Radovskaya (2007-01-10). "Кочевник был блондином". Rossiyskaya Gazeta. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ↑ See above, n. 2.

- ↑ "Early Nomads of the Altaic Region". The Hermitage. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

Sources

- Rudenko, Sergei Ivanovich (1970). Frozen Tombs of Siberia: The Pazyryk Burials of Iron Age Horsemen. University of California Press. ISBN 0520013956. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

External links

- (Russian) A library of scholarly publications about the Altai Scythians

- A collection at Novosibirsk State University site, including Pazyryk

- Pazyryk carpet, at State Hermitage Museum

- BME wiki: Pazyryk Mummies

- (Discovery Channel) Winnie Allingham, "The frozen horseman of Siberia"

- "Ancient Mummy found in Mongolia", Der Spiegel, 2004

- "Ice Maiden recreated in photographic project", Sydney Australia, 2009

- 'The Preservation of the Frozen Tombs of the Altai Mountains', UNESCO (pdf)

- http://www.mnh.si.edu/arctic/html/pdf/Rock%20Art%20and%20Archaeology%20Field%20Report%202011%20FINAL_webv4.pdf