Peace (play)

| Peace | |

|---|---|

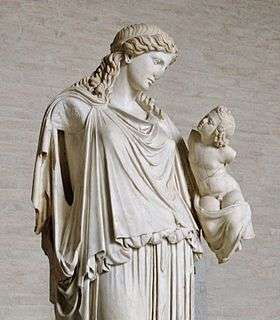

Eirene / Ploutos (Peace and Wealth): Roman copy of a work by Cephisodotus the Elder (c. 370 BC) that once stood on the Areopagus. The Dramatis Personae in ancient comedy depends on interpretation of textual evidence.[1] This list is developed from A. Sommerstein's translation.[2] | |

| Written by | Aristophanes |

| Chorus |

1.farmers 2.auxiliary chorus of citizens from various Greek states |

| Characters |

Silent roles

|

| Setting | outside a house in Athens and later in the heavens |

Peace (Greek: Εἰρήνη Eirēnē) is an Athenian Old Comedy written and produced by the Greek playwright Aristophanes. It won second prize at the City Dionysia where it was staged just a few days before the Peace of Nicias was validified (421 BC), which promised to end the ten-year-old Peloponnesian War. The play is notable for its joyous anticipation of peace and for its celebration of a return to an idyllic life in the countryside. However, it also sounds a note of caution, there is bitterness in the memory of lost opportunities and the ending is not happy for everyone. As in all Aristophanes' plays, the jokes are numerous, the action is wildly absurd and the satire is savage—Cleon, the pro-war populist leader of Athens, is once again a target for the author's wit even though he had died in battle just a few months earlier.

Peace—the plot

Short summary: Trygaeus, a middle-aged Athenian, miraculously brings about a peaceful end to the Peloponnesian War, thereby earning the gratitude of farmers while bankrupting various tradesmen who had profited from the hostilities. He celebrates his triumph by marrying Harvest, a companion of Festival and Peace, all of whom he has liberated from a celestial prison.

Detailed summary: Two slaves are frantically working outside an ordinary house in Athens, kneading unusually large lumps of dough and carrying them one by one into the stable. We soon learn from their banter that it is not dough but excrement gathered from various sources—they are feeding a giant dung beetle that their crazy master has brought home from the Mount Etna region and on which he intends flying to a private audience with the gods. This startling revelation is confirmed moments later by the sudden appearance of Trygaeus on the back of the dung beetle, rising above the house and hovering in an alarmingly unsteady manner. His two slaves, his neighbours and his children take fright and they plead with him to come back down to earth. He steadies the spirited beetle, he shouts comforting words to his children and he appeals to the audience not to distract his mount by farting or shitting any time in the next three days. His mission, he declares, is to reason with the gods about the war or, if they will not listen, he will prosecute the gods for treason against Greece. Then he soars across the stage heavenwards.

Arriving outside the house of the gods, Trygaeus discovers that only Hermes is home. Hermes informs him that the others have packed up and departed for some remote refuge where they hope never to be troubled again by the war or the prayers of humankind. He has stayed back, he says, only to make some final arrangements and meanwhile the new occupant of the house has already moved in—War. War, he says, has imprisoned Peace in a cave nearby. Just then, as chance would have it, War comes grumbling and growling outdoors, carrying a gigantic mortar in which he intends grinding the Greeks to paste. Trygaeus discovers by evesdropping that War no longer has a pestle to use with his gigantic mortar—the pestles he had hoped to use on the Greeks are both dead, for one was Cleon and the other was Brasidas, the leaders of the pro-war factions in Athens and Sparta respectively, both of whom have recently perished in battle. War goes back indoors to get himself a new one and Trygaeus boldly takes this opportunity to summon Greeks everywhere to come and help him set Peace free while there is still time. A Chorus of excited Greeks from various city-states arrives as prompted but they are so excited they cannot stop dancing at first. Eventually they get to work, pulling boulders from the cave's mouth under supervision by Trygaeus and Hermes. Some of the Greeks are more of a hindrance than a help and real progress is only made by the farmers. At last Peace and her companions, Festival and Harvest, are brought to light, appearing as visions of ineffable beauty. Hermes then tells the gathering why Peace had left them many years earlier - she had been driven away by politicians who were profiting from the war. In fact she had tried to come back several times, he says, but each time the Athenians had voted against her in their Assembly. Trygaeus apologizes to Peace on behalf of his countrymen, he updates her on the latest theatre gossip (Sophocles is now as venal as Simonides and Cratinus died in a drunken apoplexy) and then he leaves her to enjoy her freedom while he sets off again for Athens, taking Harvest and Festival back with him—Harvest because she is now his betrothed, Festival because she is to be female entertainment for the Boule or Council. The Chorus then steps forward to address the audience in a conventional parabasis.

The Chorus praises the author for his originality as a dramatist, for his courageous opposition to monsters like Cleon and for his genial disposition. It recommends him especially to bald men. It quotes songs of the 7th century BC poet Stesichorus[3] and it condemns contemporary dramatists like Carcinus, Melanthius and Morsimus. The Chorus resumes its place and Trygaeus returns to the stage. He declares that the audience looked like a bunch of rascals when seen from the heavens and they look even worse when seen up close. He sends Harvest indoors to prepare for their wedding and he delivers Festival to the archon sitting in the front row. He then prepares for a religious service in honour of Peace. A lamb is sacrificed indoors, prayers are offered and Trygaeus starts barbecuing the meat. The fragrance of roast lamb soon attracts an oracle monger who proceeds to hover about the scene in quest of a free meal, as is the custom among oracle-mongers. He is driven off with a good thrashing. Trygaeus goes indoors to prepare for his wedding and the Chorus steps forward again for another parabasis.

The Chorus sings lovingly of winter afternoons spent with friends in front of a kitchen fire in the countryside in times of peace when rain soaks into the newly sown fields and there is nothing to do but enjoy the good life. The tone soon changes however as the Chorus recalls the regimental drill and the organizational stuff-ups that have been the bane of the ordinary civilian soldier's life until now and it contemplates in bitterness the officers who have been lions at home and mere foxes in the field. The tone brightens again as Trygaeus returns to the stage, dressed for the festivities of a wedding. Tradesmen and merchants begin to arrive singly and in pairs—a sickle-maker and a jar-maker whose businesses are flourishing again now that peace has returned, and others whose businesses are failing. The sickle-maker and jar-maker present Trygaeus with wedding presents and Trygaeus offers suggestions to the others about what they can do with their merchandise: helmet crests can be used as dusters, spears as vine props, breastplates as chamber pots, trumpets as scales for weighing figs, and helmets could serve as mixing bowls for Egyptians in need of emetics or enemas. The sons of wedding guests practise their songs outdoors and one of the boys begins rehearsing Homer's epic song of war. Trygaeus sends him back indoors as he cannot stomach any mention of war. Another boy sings a famous song by Archilochus celebrating an act of cowardice and this does not impress Trygaeus either. He announces the commencement of the wedding feast and he opens up the house for celebrations: Hymen Hymenai'O! Hymen Hymenai'O!

Historical background

All the early plays of Aristophanes were written and acted against a background of war.[4] The war between Athens and Sparta had commenced with the Megarian decree in 431 BC and, under the cautious leadership of Archidamus II in Sparta and Pericles in Athens, it developed into a war of slow attrition in which Athens was unchallenged at sea and Sparta was undisputed master of the Greek mainland. Every year, the Spartans and their allies invaded Attica and wreaked havoc on Athenian farms. As soon as they retreated, the Athenians marched out from their city walls to avenge themselves on the farms of their neighbours, the Megarians and Boeotians, allies of Sparta. Till then, most Athenians had lived in rural settlements but now they congregated within the safety of the city walls. In 430 a plague decimated the over-crowded population and it also claimed the life of Pericles, leaving Athens in the control of a more radical leadership, epitomized by Cleon. Cleon was determined to gain absolute victory in the war with Sparta and his aggressive policies seemed to be vindicated in 425 in the Battle of Sphacteria, resulting in the capture of Spartan hostages and the establishment of a permanent garrison at Pylos, from where the Athenians and their allies could harass Spartan territory. The Spartans in response to this setback made repeated appeals for peace but these were dismissed by the Athenian Assembly under guidance by Cleon who wished instead to broaden the war with ambitious campaigns against Megara and Boeotia. The Athenians subsequently suffered a major defeat in Boeotia at the Battle of Delion and this was followed by an armistice in 423. By this time, however, the Spartans were increasingly coming under the influence of the pro-war leader Brasidas, a daring general who encouraged and supported revolts among Athenian client states despite the armistice. Athens' client states in Chalcidice were especially vulnerable to his intrigues. When the armistice ended, Cleon led a force of Athenians to Chalcidice to repress the revolts. It was there, while manoeuvering outside the city of Amphipolis, that he and his men were surprised and defeated by a force led by the Spartan general. Both Cleon and Brasidas died in the battle and their removal opened the way for new peace talks during the winter of 422-21. The Peace of Nicias was ratified soon after the City Dionysia, where Peace was performed, early in the spring of 421 BC.

Places and people mentioned in Peace

According to a character in Plutarch's Dinner-table Discussion,[5] (written some 500 years after Peace was produced), Old Comedy needs commentators to explain its abstruse references in the same way that a banquet needs wine-waiters. Here is the wine list for Peace as supplied by modern scholars.[6][7]

- Athenian politicians and generals

- Cleon: The populist leader of the pro-war faction in Athens, he had recently perished in the battle for Amphipolis. He is mentioned by name only once in this play (line 47) when a member of the audience is imagined comparing him to a dung beetle on the grounds that he eats dung i.e. he's dead (excrement is a characteristic element of the Aristophanic Underworld, as represented later in The Frogs). He receives several indirect mentions (313, 648, 669, 650-56) as a Cerberus whose seething (paphlagon) and shouting might yet snatch away peace (the seething image was previously developed in The Knights, where Cleon was represented as 'Paphlagonian'), a leather merchant who had corruptly profited from war, a leather skin that stifled Athenian thoughts of peace, and a rascal, chatterer, sycophant and trouble-maker that Hermes should not revile, since Hermes (as a guide to the Underworld) is now responsible for him.

- Lamachus: He was a fearless general associated with the pro-war faction but he nevertheless ratified the Peace of Nicias. He is described here as an enemy of peace who hinders peace efforts (lines 304, 473). His son is a character who sings war-like songs. Lamachus appears as the antagonist in The Acharnians and he is mentioned in another two plays.[8]

- Phormio: A successful Athenian admiral, he used to sleep rough on a soldier's pallet (line 347). He is mentioned in two other plays.[9]

- Peisander: A prominent politician, he was to become an influential figure in the Athenian coup of 411 BC. His helmet is a loathsome spectacle (line 395) and there are references to him in other plays.[10]

- Pericles: A gifted orator and politician, he provoked the war with Sparta by his Megarian decree. It is said that he did so in order to avoid being implicated in a corruption scandal involving the sculptor Pheidias (line 606). Pericles is mentioned by name in two other plays[11] and there are also indirect references to him.[12]

- Hyperbolus: Another populist, he succeeded Cleon as the new master of the speaker's stone on the Pnyx (line 681). He was a lampseller by trade and this enabled him to shed light on affairs of state (690). The Chorus would like to celebrate the wedding at the end by driving him out (1319). He is a frequent target in other plays.[13]

- Theogenes: Another prominent politician, he associated with swines (line 928). His name recurs in several plays.[14]

- Athenian personalities

- Cleonymus: A frequent butt of jokes in other plays for his gluttony and cowardice,[15] he figures here in a curse as the model of a coward (446), as a man who loves peace for the wrong reasons (673, 675) and as the father of a boy who sings lyrics by Archilochus in celebration of cowardice (1295).

- Cunna: A well-known prostitute, she has eyes that flash like those of Cleon (755). She is mentioned in another two plays.[16]

- Arriphrades: A member of an artistic family and possibly a comic poet himself,[17] he has been immortalized by Aristophanes here (line 883) and in other plays[18] as an exponent of cunnilingus.

- Glaucetes, Morychus and Teleas: Gourmands, they are imagined bustling about the replenished agora in their greedy pursuit of delicacies once peace returns (line 1008). Morychus is mentioned again in The Acharnians and The Wasps,[19] Teleas in The Birds[20] and Glaucetes in Thesmophoriazusae[21]

- Poets and other artists

- Euripides: A tragic poet renowned for his innovative plays and pathetic heroes, he appears as a ridiculous character in The Acharnians, Thesmophoriazusae and The Frogs and he receives numerous mentions in other plays. Trygaeus is warned not to fall off his beetle or he might end up as the hero of a Euripidean tragedy (line 147) and Peace is said not to like Euripides because of his reliance on legalistic quibbling for dialogue (534). Trygaeus' flight on the dung beetle is a parody of Euripides' play Bellerephon, his daughter's appeal to him is a parody of a speech from Aeolus (114-23) and there is a deliberate misquote from his play Telephus (528). The latter play was a favourite target for parody as for example in The Acharnians and Thesmophoriazusae.

- Aesop: A legendary author of fables, he is said to have inspired Trygaeus to ascend to the home of the gods on a dung beetle (line 129). In the original fable, the dung beetle flew up to the home of the gods to punish the eagle for destroying its eggs. Zeus was minding the eagle's own eggs and the dung beetle provoked him into dropping them. There are references to Aesop in two plays.[22]

- Sophocles: A famous tragic poet, he is mentioned here because his verses are evocative of the good times that will come with peace (line 531) even though he has become as greedy as Simonides (695-7). Sophocles is also mentioned in The Birds and The Frogs.[23]

- Pheidias: A renowned sculptor, he is said to have been named in a corruption scandal that was really aimed at his patron Pisistratus (line 605) and Peace is said to be a beautiful relative of his i.e. she is statuesque (616).

- Simonides: A highly respected poet, he was however notorious for demanding high fees - he'd even go to sea in a sieve if the commission was right (line 697-8). There are references to him in two other plays.[24]

- Cratinus: A comic poet often ranked with Aristophanes as a playwright, he is said to have died of a drunken apoplexy after witnessing the destruction of wine jars (line 700). He is mentioned with mock-respect in several other plays also.[25]

- Carcinus: A tragic poet, he is said to have written an unsuccessful comedy about mice (791-5) and the Muse is urged to spurn both him and his sons - his sons, who had danced in the original performance of The Wasps, are now reviled as goat-turds devoted to theatrical stunts (lines 781-95) and they are not as fortunate as Trygaeus (864). Carcinus is mentioned in several other plays.[26]

- Morsimus and Melanthius: Two brothers who were related to the great tragic poet Aeschylus but who were also known for gluttony (they are called 'Gorgons' and 'Harpies'), they collaborated on a play in which the latter acted stridently and both should be spat upon by the Muse (lines 801-816). Melanthius is imagined quoting melodramatically from his brother's play Medea when he learns that there are no more eels for sale (1009). Morsimus is mentioned in two more plays[27] and Melanthius in one other play.[28]

- Stesichorus: A famous Sicilian poet, he is quoted invoking the Muse and the Graces in a song that denounces Carcinus, Morsimus and Melanthius as inferior poets (beginning with lines 775 and 796).

- Ion: A celebrated Chian poet, he was the author of a popular song The Morning Star. Trygaeus claims to have seen him in the heavens, where he has become the Morning Star (line 835).

- Chairis: A flute player, here (line 951) as elsewhere[29] he is an execrable musician.

- Homer: The bard of all bards, he is mentioned in this play twice by name (lines 1089, 1096) and there are frequent references to his poetry. He is fancifully misquoted by Trygaeus to prove that oracle mongers are not entitled to free meals (lines 1090-93) and there is an accurate quote from a passage in the Iliad[30] arguing in favour of peace (1097-8). The son of Lamachus also concocts some Homer-like verses and he quotes from the introduction to Epigoni (1270), an epic sometimes attributed to Homer (now lost). Homer is mentioned by name in three other plays.[31]

- Archilochus: A renowned poet, he once wrote an elegy making light of his own cowardice on the battle field. The son of Cleonymus quotes from it (lines 1298-99). Archilochus is mentioned by name in two other plays.[32]

- Places

- Mount Etna: A region famous for its horses, it is from here that Trygaeus obtained his dung beetle (line 73). The mountain is mentioned again in The Birds.[33]

- Naxos: An island state, it was home to a type of boat known as a 'Naxian beetle' (line 143). The island is referred to again in Wasps.[34]

- Peiraeus: The main port for Athens, it includes a small harbour that takes its name from the Greek for 'beetle' (lines 145) and it is the sort of place where a man might excrete in public view outside a brothel (165). It is mentioned also in Knights.[35]

- Athmonon: A deme within the Cecropides tribe, it is an epithet for Trygaeus since he is enrolled there as a citizen. (lines 190, 919)

- Pylos: Enemy territory occupied by the Athenians, it is associated with missed opportunities for an end to the war (lines 219, 665).

- Prasiae: A Spartan territory, its name allows for a pun with 'leeks', one of the ingredients that War intends grinding in his mortar (line 242).

- Sicily: An island renowned for its wealth and its abundant resources, it was famous also for its cheeses, another ingredient in war's mortar (line 250). The island is mentioned in two other plays.[36]

- Samothrace: A region associated with religious mysteries, as represented in the worship of the Cabeiri, it is regarded by Trygaeus as a possible source of magic spells when all else fails (line 277).

- Thrace: The northern battleground of the Peloponnesian War, it is where War lost his Spartan pestle, Brasidas (line 283). The region is also mentioned in other plays.[37]

- Lyceum: Later famous as the school for Aristotelian philosophy, it was then a parade ground (line 356).

- Pnyx: The hill where the Athenian citizenry convened as a democratic assembly, it was topped by a monolithic rostrum called a 'bema'. Peace wants to know who is now master of the stone (line 680). The hill is mentioned in several plays.[38]

- Brauron: An Athenian town on the east coast of Attica, it was the site of a sometimes promiscuous quadrennial festival in honour of Artemis. A slave of Trygaeus wonders if Festival is a girl he had once partied with there (line 875). The town is also referred to in Lysistrata.[39]

- Oreus: A town on the western shore of Euboea, it is the home of the oracle monger and party-pooper, Hierocles (line 1047, 1125). He is associated with another Euboean town Elymnion (1126).

- Lake Copais: A lake in Boeotia, it is a source of eels much valued by Athenian gourmands (1005). It is mentioned for the same reason in The Acharnians.[40]

- Sardis: Once the capital of the Lydian empire and subsequently of a Persian satrapy, it is a source of scarlet dye used to denote the cloaks of Athenian officers (line 1174). It is mentioned in two other plays.[41]

- Cyzicus: A town on the Propontis, it is a source of saffron-coloured (or crap-coloured) dye (1176).

- Pandion's statue: A statue of a mythical king of ancient Athens, it was located in the agora as a rallying point for the Pandionid tribe (line 1183). Both Aristophanes and Cleon would have mustered here since both belonged to the Cydathenaeum deme, a branch of the Pandionid tribe.

- Foreigners

- Ionians: Inhabiting region of islands and coastal cities scattered around the Aegean, they formed the core of the Athenian empire. An Ionian in the audience is imagined to say that the beetle represents Cleon since they both eat shit (line 46). The Ionian dialect allows a pun equating 'sheep' with 'oh!' (930-33).

- Medes: Brothers to the Persians and often identified with them as rivals of Greece, they benefit from the ongoing war between Athens and Sparta (line 108). They are mentioned quite often in other plays.[42]

- Chians: Citizens of the island state of Chios, they seem to have been recent victims of an Athenian law imposing a fine of 30 000 drachmas on any allied state in which an Athenian citizen happened to be killed. They might have to pay such a fine if Trygaeus falls off his dung beetle (line 171). Chios is also the home of a popular poet, Ion (835). The island is referred to in three other plays.[43]

- Megarians: Long-time rivals of Athens and allies of Sparta, they are the garlic in War's mortar (line 246-249), they are a hindrance to peace efforts even though they are starving (481-502) and they were the target of the Megarian decree, the original cause of the war (609). They are mentioned in other plays,[44] but especially in The Acharnians where one of the characters is a starving Megarian farmer.

- Brasidas: Sparta's leading general, he had recently perished in the battle for Amphipolis. He is mentioned indirectly as one of the pestles that War can no longer use (line 282) and directly as somebody whose name is often brought up by corrupt politicians in accusations of treason (640). He is mentioned also in Wasps.[45]

- Datis: A Persian general during the Persian Wars, he is imaginatively quoted as somebody who sings while masturbating (line 289) - meanwhile Trygaeus and his fellow Greeks spring into action.

- Cillicon: A traitor (from Miletus) who famously excused his treachery with the comment that he intended nothing bad. He is quoted by Trygaeus (line 363).

- Boeotians: Northern neighbours of Athens but allies of Sparta, they were hindering peace efforts (line 466) and their banned produce is fondly remembered (1003). They are mentioned in other plays[46] and especially in The Acharnians, where one of the characters is a Boetian merchant.

- Argives: Citizens of Argos and neighbours of the Spartans, they had maintained their neutrality throughout the war and they were not assisting in peace efforts (lines 475, 493). They receive mentions in other plays.[47]

- Thrassa and Syra: Common names for female slaves of Thracian (line 1138) and Syrian origin (1146). Thrassa is a silent character in Thesmophoriazusae and the name recurs in two other plays.[48]

- Egyptians: An ancient and exotic people whose customs, as described by Herodotus, included the regular use of an emetic syrmaia.[49] They are mentioned in that context here (line 1253) and they receive mentions in other plays.[50]

- Religious and cultural identities

- Pegasus: A mythical flying horse, it lends its name to the flying dung beetle (lines 76, 135, 154).

- Dioscuri: Otherwise known as Castor and Pollux, they were venerated in particular by Spartans. Trygaeus attributes the death of Brasidas to their intervention (line 285).

- Eleusinian mysteries: A mystery religion dedicated to the worship of Demeter and promising immortal life to its initiates, it included the ritual bathing of piglets. Trygaeus asks Hermes for money to buy such a piglet (374-5) and he offers to dedicate the mysteries to Hermes if he helps to secure peace (420).

- Panathenaea: The most important annual festival of Athens, it was dedicated to Athena. Trygaeus offers to dedicate it to Hermes in exchange for his help (line 418). He also offers to celebrate in his honour the Dipolia (festival of Zeus) and the Adonia (420). The Panathenaea is mentioned also in The Clouds and The Frogs.[51] Diipoleia is also mentioned in The Clouds[52] and Adonia in Lysistrata.[53]

- Enyalius: An epithet of Ares, it is often used in the Iliad. The Chorus bids Trygaeus not to use this epithet in an invocation to the gods because Ares has nothing to do with peace (line 457).

- Ganymede: Zeus's cupbearer, he is said to be the future source of the ambrosia on which the dung beetle will feed in future.

- Isthmian Games: One of the great athletic festivals of ancient Greece, it was a venue for camping both by athletes and spectators. A slave of Trygaeus fondly imagine his penis sharing a tent there with Festival (line 879).

- Apaturia: A festival celebrated by Ionian Greeks, it included a day of sacrifice known as Anarrhysisor Drawing back. This word has sexual connotations for members of the Boule (line 890) in anticipation of an orgy with Festival.

- Lysimache: An epithet for Peace and the name of a contemporary priestess of Athena Polias (line 992).

- Stilbades: One of the prophets or oracle mongers that had profited from the war, he is imagined weeping from the smoke that rises from the sacrificial offering to Peace (line 1008).

- Bakis: A popular prophet and source of oracles, he is mentioned repeatedly by the oracle monger Hierocles (lines 1070-72) and Hierocles is later referred to as Bakis (1119). He is frequently cited in The Knights[54] and he is mentioned also in The Birds[55]

- Sibyl: A legendary prophetess, she is considered by Hierocles to be a greater authority than Homer (line 1095) and he is told to eat her (1116). She is mentioned also in The Knights.[56]

Discussion

Aristophanes' plays reveal a tender love of rural life and a nostalgia for simpler times[57] and they develop a vision of peace involving a return to the country and its routines.[58] The association of peace with rural revival is expressed in this play in terms of religious imagery: Peace, imprisoned in a cave guarded by a Cerberus figure (lines 313-15), resembles a chthonic fertility goddess in captivity in the underworld, a motif especially familiar to Athenians in the cult of Demeter and her daughter Kore in the Eleusinian mysteries. The action of the play however also borrows from ancient folklore - the rescue of a maiden or a treasure from the inaccessible stronghold of a giant or monster was already familiar to Athenians in the story of Perseus and Andromeda and it is still familiar to modern audiences as 'Jack and the Beanstalk' (Trygaeus like Jack magically ascends to the remote stronghold of a giant and plunders its treasure).[59] In spite of these mythical and religious contexts, political action emerges in this play as the decisive factor in human affairs - the gods are shown to be distant figures and mortals must therefore rely on their own initiative, as represented by the Chorus of Greeks working together to release Peace from captivity.[60]

The god Hermes delivers a speech blaming the Peloponnesian War on Pericles and Cleon (lines 603-48) and this was an argument that Aristophanes had already promoted in earlier plays (e.g. The Acharnians 514-40 and The Knights 792-809). The Chorus's joyful celebration of peace is edged with bitter reflections on the mistakes of past leaders (e.g. 1172-90) and Trygaeus expresses anxious fears for the future of the peace (e.g. 313-38) since events are still subject to bad leadership (as symbolized by the new pestle that War goes indoors to fetch).. The bankrupted tradesmen at the end of the play are a reminder that there is still support for war. Moreover, the militaristic verses borrowed from Homer by the son of Lamachus are a dramatic indication that war is deeply rooted in culture and that it still commands the imagination of a new generation. Peace in such circumstances requires not only a miracle (such as Trygaeus' flight) but also a combination of good luck and good will on the part of a significant group within the community (such as farmers) - a sober assessment by the poet of Dionysus.

Peace and Old Comedy

Peace is structured according to the conventions of Old Comedy. Variations from those conventions may be due to an historical trend towards New Comedy, corruption of the text and/or a unique dramatic effect that the poet intended. Noteworthy variations in this play are found in the following elements:

- Agon: A conventional agon is a debate that decides or reflects the outcome of the play, comprising a 'symmetrical scene' with a pair of songs and a pair of declaimed or spoken passages, typically in long lines of anapests. There is no such agon in this play nor is there an antagonist to represent a pro-war viewpoint, apart from War, a monstrosity incapable of eloquence. However, Old Comedy is rich in symmetrical scenes and sometimes these can resemble an agon. There is a symmetrical scene in lines 346-425 (song-dialogue-song-dialogue) in which Trygaeus argues with Hermes and eventually wins his support. The dialogue however is in iambic trimeter, conventionally the rhythm of ordinary speech. Moreover, the song's metrical form is repeated much later in a second antistrophe (583-97), indicating that Aristophanes was aiming at something other than an agon.

- Parabasis: A conventional parabasis is an address to the audience by the Chorus and it includes a symmetrical scene (song-speech-song-speech). Typically there are two such addresses, in the middle and near the end of a play. Peace follows convention except that the speeches have been omitted from the symmetrical scene in the first parabasis (lines 729-816) and it includes several lines (752-59) that were copied almost verbatim from the first parabasis in The Wasps ( The Wasps 1030-37). The repetition of these lines need not indicate a problem with the text; it could instead indicate the poet's satisfaction with them.[61] They describe Cleon as a disgusting gorgon-like phenomenon in language that matches sound and sense e.g.

- ἑκατὸν δὲ κύκλῳ κεφαλαὶ κολάκων οἰμωξομένων ἑλιχμῶντο

- περὶ τὴν κεφαλήν (Wasps 1033-4, Peace 756-7):

- "a hundred heads of doomed stooges circled and licked around his head"

- The sound of something revolting is captured in the original Greek by the repetition of the harsh k sound, including a repetition of the word for 'head'.

- Dactylic rhythm: The metrical rhythms of Old Comedy are typically iambic, trochaic and anapestic. Peace however includes two scenes that are predominantly dactylic in rhythm, one featuring the oracle-monger Hierocles (1052–1126) and the other featuring the epic-singing son of Lamachus (1270–97). In both scenes, the use of dactyls allows for Homer-like utterances generally signifying martial and oracular bombast.

- Parodos: A parodos is the entry of the Chorus, conventionally a spectacular occasion for music and choreography. Often it includes trochaic rhythms to signify the mood of an irascible Chorus in search of trouble (as for example in The Acharnians and The Knights). In Peace the rhythm is trochaic but the Chorus enters joyfully and its only argument with the protagonist is over its inability to stop dancing (299-345), an inventive use of a conventional parados.

Standard edition

The standard critical edition of the Greek text (with commentary) is: S. Douglas Olson (ed.), Aristophanes Peace (Oxford University Press, 1998)

Translations

- William James Hickie, 1853 - prose, full text

- Benjamin B. Rogers, 1924 - verse

- Arthur S. Way, 1934 - verse

- Alan Sommerstein, 1978 - prose

- George Theodoridis, 2002 - prose: full text

- Unknown translator - prose: full text

See also

References

- ↑ Aristophanes:Lysistrata, The Acharnians, The Clouds, Alan Sommerstein, Penguin Classics 1973, page 37

- ↑ Aristophanes:The Birds and Other Plays D. Barrett and A. Sommerstein, Penguin Classics 1978

- ↑ Aristophanes:The Birds and Other Plays D. Barrett and A. Sommerstein, Penguin Classics page 325 note 53

- ↑ For an overview see for example the introduction to Aristophanes:Peace S. Douglas Olson, Oxford University Press 2003, pages XXV-XXXI

- ↑ Dinner-table Discussion Book VII No.8, quoted in Aristophanes:The Birds and Other Plays D. Barrett and A. Sommerstein (translators), Penguin Classics 1978, pages 14-15

- ↑ Aristophanes:The Birds and Other Plays D. Barrett and A Sommerstein, Penguin Classics 1978, Notes

- ↑ Aristophanis Comoediae Tomus II F. Hall and W.Geldart, Oxford University Press 1907, Index Nominum

- ↑ Thesmophoriazusae line 841; Frogs 1039

- ↑ Knights 562; Lysistrata 804

- ↑ Birds line 1556; Lysistrata 490

- ↑ Knights 283, Clouds 213

- ↑ Acharnians 530; Clouds 859

- ↑ Acharnians 846; Knights 1304, 1363; Clouds 551, 557, 623, 876, 1065; Wasps 1007; Thesmophoriazusae 840; Frogs 570

- ↑ Wasps line 1183; Birds 822, 1127, 1295; Lysistrata 63

- ↑ Acharnians lines 88, 844; Knights 958, 1294, 1372; Clouds 353, 400, 673-5, 680; Wasps 19, 20, 822; Birds 289, 290, 1475; Thesmophoriazusae 605

- ↑ Knights line 765; Wasps 1032

- ↑ Aristophanes:Wasps D.MacDowell, Oxford University Press 1971, pages 297-8 notes 1278-1280

- ↑ Knights line 1281; Wasps 1280; Ecclesiazusae 129

- ↑ Acharnians 887; Wasps 506, 1142

- ↑ The Birds 168, 1025

- ↑ Thesmophoriazusae 1033

- ↑ Wasps lines 566, 1401, 1446; Birds 471, 651

- ↑ The Birds line 100; Frogs 76, 79, 787, 1516

- ↑ The Clouds line 1356, 1362; Birds 919

- ↑ Acharnians lines 849, 1173; Knights 400, 526; Frogs 357

- ↑ Clouds 1261; Wasps 1501-12; Thesmophoriazusae 441

- ↑ Knights 401; Frogs 151

- ↑ Birds 151

- ↑ Acharnians 16; Birds 857

- ↑ Iliad IX 63-4

- ↑ Clouds line 1056; Birds 575, 910, 914; Frogs 1034

- ↑ Acharnians 120; Frogs 764

- ↑ Birds 926

- ↑ Wasps line 355

- ↑ Knights line815, 855

- ↑ Wasps line 838, 897; Lysistrata 392

- ↑ Acharnians lines 136, 138, 602; Wasps 288; Birds 1369; Lysistrata 103

- ↑ Knights 42, 165, 749, 751; Wasps 31; Thesmophoriazusae 658; Ecclesiazusae 243, 281, 283

- ↑ Lysistrata line 645

- ↑ The Acharnians lines 880, 883, 962

- ↑ Acharnians line 112; Wasps 1139

- ↑ Knights lines 478, 606 781; Wasps 12, 1097; Birds 277; Lysistrata 653, 1253; Thesmophoriazusae 337, 365; Frogs 938

- ↑ Birds 879; Frogs 970; Ecclesiazusae 1139

- ↑ Wasps line 57; Lysistrata 1170;

- ↑ Wasps line 475

- ↑ Knights line 479; Lysistrata 35, 40, 72, 86, 702

- ↑ Knights 465-6, 813; Thesmophoriazusae 1101; Frogs 1208; Wealth II 601

- ↑ Acharnians line 273; Wasps 828

- ↑ Herodotus II.77

- ↑ Birds lines 504, 1133; Frogs 1206, 1406; Thesmophoriazusae 856, 878; Wealth II 178;

- ↑ Clouds lines 386, 988; Frogs 1090

- ↑ Clouds line 984

- ↑ Lysistrata 393, 389

- ↑ Knights lines 123, 124, 1003 etc.

- ↑ Birds lines 962, 970

- ↑ Knights line 61

- ↑ Ancient Greece:A Political, Social and Cultural History S.B.Pomeroy, S.M.Burstein and W.Donlan, Oxford University Press US 1998, page 301

- ↑ A Short History of Greek Literature Jacqueline de Romilly, University of Chicage Press 1985, page 88

- ↑ Aristophanes:Peace S. Douglas Olson, Oxford University Press 2003, Introduction pages XXXV-VIII

- ↑ Aristophanes:Peace S. Douglas Olson, Oxford University Press 2003, Introduction pages XL-XLI

- ↑ Aristophanes:Wasps Douglas MacDowell, Oxford University Press 1971, note 1030-7 page 265

External links

-

Works related to Peace at Wikisource

Works related to Peace at Wikisource -

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Εἰρήνη

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Εἰρήνη