Amphipolis

| Amfipoli Αμφίπολη | |

|---|---|

|

Amfipolis municipality | |

Amfipoli | |

|

Location within the region  | |

| Coordinates: 40°49′N 23°50′E / 40.817°N 23.833°ECoordinates: 40°49′N 23°50′E / 40.817°N 23.833°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Central Macedonia |

| Regional unit | Serres |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 414.3 km2 (160.0 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipality | 9,182 |

| • Municipality density | 22/km2 (57/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 2,615 |

| Community[1] | |

| • Population | 185 (2011) |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) |

| Vehicle registration | ΕΡ |

Amphipolis (Modern Greek: Αμφίπολη; Ancient Greek: Ἀμφίπολις, Amfípolis)[2] is best known for the magnificent ancient Greek city (polis), and later Roman city, whose impressive remains can still be seen.

It is famous in history for events such as the battle between the Spartans and Athenians in 422 BC, and also as the place where Alexander the Great prepared for campaigns leading to his invasion of Asia.[3] Alexander's three finest admirals, Nearchus, Androsthenes and Laomedon, resided in this city and it is also the place where, after Alexander's death, his wife Roxane and their small son Alexander IV were exiled and later murdered.

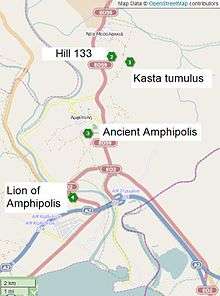

Excavations in and around the city have revealed important buildings, ancient walls and tombs. At the nearby vast Kasta burial mound, an important ancient Macedonian tomb has recently been revealed. The unique and beautiful "Lion of Amphipolis" monument nearby is a popular destination for visitors.

It is today a municipality in the Serres regional unit of Greece. The seat of the municipality is Rodolivos.[4]

History

Origins

Throughout the 5th century BC, Athens sought to consolidate its control over Thrace, which was strategically important because of its primary materials (the gold and silver of the Pangaion hills and the dense forests essential for naval construction), and the sea routes vital for Athens' supply of grain from Scythia. After a first unsuccessful attempt at colonisation in 497 BC by the Milesian Tyrant Histiaeus, the Athenians founded a first colony at Ennea-Hodoi (‘Nine Ways’) in 465, but these first ten thousand colonists were massacred by the Thracians.[5] A second attempt took place in 437 BC on the same site under the guidance of Hagnon, son of Nicias, which was successful. The city and its first walls date from this time.

The new settlement took the name of Amphipolis (literally, "around the city"), a name which is the subject of much debate about its etymology. Thucydides claims the name comes from the fact that the Strymon flows "around the city" on two sides;[6] however a note in the Suda (also given in the lexicon of Photius) offers a different explanation apparently given by Marsyas, son of Periander: that a large proportion of the population lived "around the city". However, a more probable explanation is the one given by Julius Pollux: that the name indicates the vicinity of an isthmus.

Amphipolis became the main power base of the Athenians in Thrace and, consequently, a target of choice for their Spartan adversaries. The Athenian population remained very much in the minority in the city.[7] For this reason Amphipolis remained an independent city and an ally of the Athenians, rather than a colony or member of the confederacy. However, in 424 BC the Spartan general Brasidas easily took control of the city.

A rescue expedition led by the Athenian general, and later historian, Thucydides had to settle for securing Eion and could not retake Amphipolis, a failure for which Thucydides was sentenced to exile. A new Athenian force under the command of Cleon failed once more in 422 BC during the Battle of Amphipolis at which both Cleon and Brasidas lost their lives. Brasidas survived long enough to hear of the defeat of the Athenians and was buried at Amphipolis with impressive pomp. From then on he was regarded as the founder of the city[8][9][10] and honoured with yearly games and sacrifices.

Macedonian rule

The city itself kept its independence until the reign of king Philip II (r. 359–336 BC) despite several Athenian attacks, notably because of the government of Callistratus of Aphidnae. In 357 BC, Philip succeeded where the Athenians had failed and conquered the city, thereby removing the obstacle which Amphipolis presented to Macedonian control over Thrace. According to the historian Theopompus, this conquest came to be the object of a secret accord between Athens and Philip II, who would return the city in exchange for the fortified town of Pydna, but the Macedonian king betrayed the accord, refusing to cede Amphipolis and laying siege to Pydna as well.[11]

The city was not immediately incorporated into the Macedonian kingdom, and for some time preserved its institutions and a certain degree of autonomy. The border of Macedonia was not moved further east; however, Philip sent a number of Macedonian governors to Amphipolis, and in many respects the city was effectively "Macedonianized". Nomenclature, the calendar and the currency (the gold stater, created by Philip to capitalise on the gold reserves of the Pangaion hills, replaced the Amphipolitan drachma) were all replaced by Macedonian equivalents. In the reign of Alexander the Great, Amphipolis was an important naval base, and the birthplace of three of the most famous Macedonian admirals: Nearchus, Androsthenes[12] and Laomedon, whose burial place is most likely marked by the famous lion of Amphipolis.

The importance of the city in this period is shown by Alexander the Great's decision that it was one of the six cities at which large luxurious temples costing 1500 talents were built. Alexander prepared for campaigns here against Thrace in 335BC and the his army and fleet assembled near the port before the invasion of Asia. The port was also used as naval base during his campaigns in Asia. After Alexander's death, his wife Roxane and their small son Alexander IV were exiled by Cassander and later murdered here.[13]

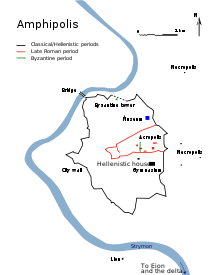

Throughout Macedonian sovereignty Amphipolis was a strong fortress of great strategic and economic importance, as shown by inscriptions. Amphipolis became one of the main stops on the Macedonian royal road (as testified by a border stone found between Philippi and Amphipolis giving the distance to the latter), and later on the Via Egnatia, the principal Roman road which crossed the southern Balkans. Apart from the ramparts of the lower town, the gymnasium and a set of well-preserved frescoes from a wealthy villa are the only artifacts from this period that remain visible. Though little is known of the layout of the town, modern knowledge of its institutions is in considerably better shape thanks to a rich epigraphic documentation, including a military ordinance of Philip V and an ephebarchic law from the gymnasium.

Conquest by the Romans

After the final victory of Rome over Macedonia in a battle in 168 BC, Amphipolis became the capital one of the four mini-republics, or merides, which were created by the Romans out of the kingdom of the Antigonids which succeeded Alexander’s empire in Macedon. These merides were gradually incorporated into the Roman client state, and later province, of Thracia. According to the Acts of the Apostles, the apostles Paul and Silas passed through Amphipolis in the early 50s AD, on their journey between Philippi and Thessalonica.[14]

Revival in Late Antiquity

During the period of Late Antiquity, Amphipolis benefited from the increasing economic prosperity of Macedonia, as is evidenced by the large number of Christian churches that were built. Significantly however, these churches were built within a restricted area of the town, sheltered by the walls of the acropolis. This has been taken as evidence that the large fortified perimeter of the ancient town was no longer defendable, and that the population of the city had considerably diminished.

Nevertheless, the number, size and quality of the churches constructed between the fifth and sixth centuries are impressive. Four basilicas adorned with rich mosaic floors and elaborate architectural sculptures (such as the ram-headed column capitals - see picture) have been excavated, as well as a church with a hexagonal central plan which evokes that of the basilica of St. Vitalis in Ravenna. It is difficult to find reasons for such municipal extravagance in such a small town. One possible explanation provided by the historian André Boulanger is that an increasing ‘willingness’ on the part of the wealthy upper classes in the late Roman period to spend money on local gentrification projects (which he terms euergetism, from the Greek verb εύεργετέω, (meaning 'I do good') was exploited by the local church to its advantage, which led to a mass gentrification of the urban centre and of the agricultural riches of the city’s territory. Amphipolis was also a diocese under the metropolitan see of Thessalonica - the Bishop of Amphipolis is first mentioned in 533. The bishopric is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[15]

Final decline of the city

The Slavic invasions of the late 6th century gradually encroached on the back-country Amphipolitan lifestyle and led to the decline of the town, during which period its inhabitants retreated to the area around the acropolis. The ramparts were maintained to a certain extent, thanks to materials plundered from the monuments of the lower city, and the large unused cisterns of the upper city were occupied by small houses and the workshops of artisans. Around the middle of the 7th century AD, a further reduction of the inhabited area of the city was followed by an increase in the fortification of the town, with the construction of a new rampart with pentagonal towers cutting through the middle of the remaining monuments. The acropolis, the Roman baths, and especially the episcopal basilica were crossed by this wall.

The city was probably abandoned in the eighth century, as the last bishop was attested in 787. Its inhabitants probably moved to the neighbouring site of ancient Eion, port of Amphipolis, which had been rebuilt and refortified in the Byzantine period under the name “Chrysopolis”. This small port continued to enjoy some prosperity, before being abandoned during the Ottoman period. The last recorded sign of activity in the region of Amphipolis was the construction of a fortified tower to the north in 1367 by the megas primikerios John and the stratopedarches Alexios to protect the land that they had given to the monastery of Pantokrator on Mount Athos.

Archaeology

The site was discovered and described by many travellers and archaeologists during the 19th century, including E. Cousinéry (1831) (engraver), L. Heuzey (1861), and P. Perdrizet (1894–1899). However, excavations did not truly begin until after the Second World War. The Greek Archaeological Society under D. Lazaridis excavated in 1972 and 1985, uncovering a necropolis, the city wall (see photograph), the basilicas, and the acropolis. Further excavations have since uncovered the river bridge, the gymnasium, Greek and Roman villas and numerous tombs etc.

Parts of the lion monument and tombs were discovered during World War I by Bulgarian and British troops whilst digging trenches in the area. In 1934, M. Feyel, of the École française d'Athènes, led an epigraphical mission to the site and uncovered further remains of the lion monument (a reconstruction was given in the Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique, a publication of the EfA which is available on line).[16]

The silver ossuary containing the cremated remains of Brasidas[17] and a gold crown (see image) was found in a tomb in pride of place under the Agora.

The Tomb of Amphipolis

In 2012[18] Greek archaeologists unearthed a large tomb within the Kasta Hill, the biggest burial mound in Greece, northeast of Amphipolis. The large size of the tumulus indicates the prominence of the burials made there. The perimeter wall of the tumulus is 497 meters long, and is made of limestone covered with marble.

The tomb comprises three chambers separated by walls. There are two sphinxes just outside the entrance to the tomb. Two of the columns supporting the roof in the first section are in the form of Caryatids, in the 4th century BC style. The excavation revealed a pebble mosaic showing the abduction of Persephone by Hades directly behind the Caryatids and in front of the Macedonian marble door leading to the "third" chamber. Hades' chariot is drawn by two white horses and led to the underworld by Hermes. The mosaic verifies the Macedonian character of the tomb. As the head of one of the sphinxes was found inside the tomb behind the broken door, it is clear that there were intruders, probably in antiquity.

The identity of the burial remains unknown and the excavation is continuing.[19] Dr. Katerina Peristeri, the archaeologist heading the excavation of the tomb, dates the tomb to the 4th Century BC, the period after the death of Alexander the Great (323 BC).

Amphipolitans

- Demetrius of Amphipolis, student of Plato's

- Zoilus (400 BC-320 BC), grammarian, cynic philosopher

- Pamphilus (painter), head of Sicyonian school and teacher of Apelles

- Aetion, sculptor

- Philippus of Amphipolis, historian

- Nearchus, admiral

- Erigyius, general

- Damasias of Amphipolis 320 BC Stadion Olympics

- Hermagoras of Amphipolis (c. 225 BC), stoic philosopher, follower of Persaeus

- Apollodorus of Amphipolis, appointed joint military governor of Babylon and the other satrapies as far as Cilicia by Alexander the Great[20]

In popular culture

The fictional character Xena, of the show Xena: Warrior Princess, was from the city of Amphipolis.

Gallery

-

Coins from Amphipolis.

-

Ram-headed capital of a column from a pre-Christian temple.

-

British soldiers of the 2nd King's Shropshire Light Infantry with skulls excavated during the construction of trenches and dugouts at site of Amphipolis during World War I, 1916.

-

Amphipolis Lion - early excavations.

-

Amphipolis archaeological museum.

See also

References

- 1 2 "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- ↑ "Amfípolis: Greece, name, administrative division, geographic coordinates and map". Geographical Names. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ↑ "Amphipolis", Ministry of Culture: ISBN 960-214-126-3

- ↑ Kallikratis law Greece Ministry of Interior (Greek)

- ↑ Thucydides I, 100, 3

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-12-09. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-12-09. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-12-09. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- ↑ Koukouli-Chrysanthaki Ch., "Excavating Classical Amphipoli", In (eds) Stamatopoulou M., and M., Yeroulanou <Excavating Classical Culture>, BAR International Series 1031, 2002:57-73

- ↑ Agelarakis A., “Physical anthropological report on the cremated human remains of an individual retrieved from the Amphipolis agora”, In “Excvating Classical Amphipolis” by Koukouli-Chrysantkai Ch., <Excavating Classical Culture> (eds.) Stamatopoulou M., and M., Yeroulanou, BAR International Series 1031, 2002: 72-73.

- ↑ Theopompus, Philippica

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?um=1&q=Androsthenes+Thasos&btnG=Search+Books

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, Library of History Book XIX, 52

- ↑ Acts 17:1

- ↑ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 831

- ↑ Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique (French)

- ↑ A. Agelarakis, “Physical anthropological report on the cremated human remains of an individual retrieved from the Amphipolis agora”, In “Excvating Classical Amphipolis” by Ch. Koukouli-Chrysantkai, <Excavating Classical Culture> (eds.) Stamatopoulou M., and M., Yeroulanou, BAR International Series 1031, 2002: 72-73

- ↑ Andrew Marszal (7 September 2014). "Marble female figurines unearthed in vast Alexander the Great-era Greek tomb". www.telegraph.co.uk. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ↑ "Greek tomb at Amphipolis is 'important discovery'". BBC News. 12 August 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus Library of History Book XVII

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amphipolis. |

- Official site about Amphipolis

- Demographic Information from Greek Travel Pages

- Livius.org: Amphipolis

- The tomb of Amphipolis