Phenakistoscope

The phénakisticope (better known by the later misspelling "phenakistoscope") was the first widespread animation device that created a fluent illusion of motion. The phenakistoscope is regarded as one of the first forms of moving media entertainment that paved the way for the future motion picture and film industry.[1] It can be compared to a GIF animation as it has a short duration and plays as a loop until the viewer stops it.

Etymology and spelling

The term 'phénakisticope' was explained in its introduction in Le Figaro in June 1833 to be from the root Greek word 'phenakisticos' (or rather φενακίζειν - phenakizein), meaning "to deceive" or "to cheat", and ὄψ - óps, meaning "eye" or "face",[2] so it was probably intended as a transliteration of 'optical deception' or 'optical illusion'.

The term phénakisticope was possibly first used by the French company Alphonse Giroux et Compagnie in their application for an import license (29 May 1833) and this name was used on their box sets.[3] Fellow Parisian publishers Junin & Lazard used the term 'phenakisticope' without the accent.[4]

Inventor Joseph Plateau did not give a name for the device when he first published about it in January 1833, but used 'phénakisticope' later that year in another article to refer to the published versions he was not involved with. By then, he had an authorized set published as "Fantascope".[5] An earlier edition of this set was called "Phantasmascope".

The spelling 'phenakistiscope' was possibly introduced by lithographers Forrester & Nichol in collaboration with optician John Dunn; they used the title "The Phenakistiscope, or, Magic Disc" for their box sets, as advertised in September 1833.[6] The corrupted part of the word, 'scope', was understood to be derived from Greek 'skopos', meaning "aim", "target", "object of attention" or "watcher", "one who watches" and was quite common in the naming of optical devices (e.g. Telescope, Microscope, Kaleidoscope, Fantascope, Bioscope).

Currently the misspelling 'phenakistoscope' seems to be most commonly used.

Technology

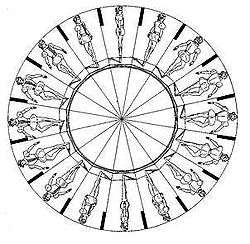

The phénakisticope used a spinning cardboard disc attached vertically to a handle. Arrayed around the disc's center was a series of pictures showing phases of the animation, and cut through it was a series of equally spaced radial slits. The user would spin the disc and look through the moving slits at the disc's reflection in a mirror. The scanning of the slits across the reflected images kept them from simply blurring together, so that the user would see a rapid succession of images that appeared to be a single moving picture.

When there is the same number of images as slots, the images will animate in a fixed position, but will not drift across the disc. Fewer images than slots, and the images will drift in the opposite direction to that of the spinning disc. More images than slots, and the images will drift in the same direction as the spinning disc.[7]

Unlike the zoetrope and other successors, the phénakisticope could only practically be used by one person at a time.

The pictures of the phénakisticope became distorted when spun fast enough to produce the illusion of movement; they appeared a bit slimmer and were slightly curved. Sometimes animators drew an opposite distortion in their pictures to compensate this. However, most animations were not intended to give a realistic representation and the distortion isn't very obvious in cartoonish pictures.

The distortion and the flicker caused by the rotating slits are not seen in most phénakisticope animations now found online (for instance the GIF animation on this page). These are usually re-animations created with software and do not replicate the actual viewing experience of a phénakisticope, but they can present the work of the animators in an optimized fashion. Some miscalculated modern re-animations also have the slits rotating, which would appear still when viewed through an actual phénakisticope. This also results in the figures moving across the discs where they were supposed to stand still.

Most commercially produced discs are lithographic prints that were colored by hand, although multicolor lithography and other printing techniques were used by some manufacturers.

Variations

Many versions of the phénakisticope used smaller illustrated uncut cardboard discs that had to be placed on a larger slotted disc. A common variant had the illustrated disc on one end of a brass axis and the slotted disc on the other end; this was slightly more unwieldy but needed no mirror and was claimed to produce clearer images.

Fores offered an Exhibitor: a handle for two slotted discs with the pictures facing each other which allowed two viewers to look at the animations at the same time, without a mirror.

A few discs had a shaped edge on the cardboard to allow for the illusion of figures crawling over the edge. Ackermann & Co published three of those discs in 1833, including one by inventor Joseph Plateau.

Some versions added a wooden stand with a hand-cranked mechanism to spin the disc.

Several phénakisticope projectors with glass discs were produced and marketed since the 1850s, but they never became mainstream.[8]

Stereoscopic versions of the phénakisticope were experimented with, but none seemed very successful.

Invention

The phenakisticope was invented almost simultaneously in November or December 1832 by the Belgian physicist Joseph Plateau and the Austrian professor of practical geometry Simon Stampfer.

In some early experiments Plateau noticed that when looking from a small distance at two concentric cogwheels which turned fast in opposite directions, it produced the optical illusion of a motionless wheel. He later read Peter Mark Roget's 1824 article Explanation of an optical deception in the appearance of the spokes of a wheel when seen through vertical apertures which addressed the same illusion. Plateau decided to investigate the phenomenon further and later published his findings in Correspondance Mathématique et Physique in 1828[9] and 1830.[10] Early in 1831, Michael Faraday published his article "On a peculiar Class of Optical Illusions" about very similar findings. Some new details, like looking at the reflection of a wheel in the mirror through its own cogs, inspired Plateau to do more experiments. After several attempts and many difficulties he constructed a working model of the phénakisticope in November or December 1832. Plateau published his invention in a January 21, 1833 letter to Correspondance Mathématique et Physique. The article was titled Sur un nouveau genre d'illusions d'optique (On a new type of optical illusion) and did not mention a name for the device. It was illustrated with a plate of a pirouetting dancer printed as a black outline, with Plateau suggesting it would be more effective when shaded and colored.[11]

Stampfer read about Faraday's findings in December 1832 and was inspired to do similar experiments, that soon led to his invention of what he called Stroboscopischen Scheiben oder optischen Zauberscheiben (stroboscope discs or optical magic discs). Stampfer had thought of placing the sequence of images on either a disc, a cylinder (like the later zoetrope) or, for a greater number of images, on a long, looped strip of paper or canvas stretched around two parallel rollers (like film would later be looped). He also suggests covering up most of the disc or the mirror with a cut-out sheet of cardboard so that one sees only one of the moving figures, and painting theatrical coulisses and backdrops around the cut-out part. Stampfer also mentioned a version which has a disc with pictures on one end and a slotted disc on the other side of an axis, but he found spinning the disc in front of a mirror more simple. By February 1833 he had prepared six double-sided discs, which were soon published by Trentsensky & Vieweg. Matthias Trentsensky and Stampfer were granted an Austrian patent (k.k. Privilegium) for the discs on 7 May 1833.[12]

Publisher and Plateau's doctoral advisor Adolphe Quetelet claimed to have received a working model to present to Faraday as early as November 1832.[13] Plateau mentioned in 1836 that he thought it difficult to state the exact time when he got the idea, but he believed he was first able to successfully assemble his invention in December. He stated to trust the assertion of Stampfer to have invented his version at the same time.[14]

Peter Mark Roget claimed in 1834 to have constructed several phénakisticopes and showed them to many friends as early as in the spring of 1831, but as a consequence of more serious occupations he did not get around to publishing any account of his invention.[15]

Commercial production

Publishers Trentsensky & Vieweg probably produced the first edition of Professor Stampfer's Stroboscopische Scheiben soon after they were ready in February 1833, but possibly they waited until their Privilegium was granted on 7 May 1833. They were not prepared for the immediate success; it sold out within four weeks and left them unable to ship orders.[12] These discs probably had round holes as illustrated in an 1868 article[16] and a 1922 reconstruction by William Day,[17] but no original copies are known to still exist. Trentsensky & Vieweg published an improved and expanded set of eight double-sided discs with vertical slits in July 1833. English editions were published not much later with James Black and Joseph Myers & Co. A total of 28 different disc designs have been credited to Professor Stampfer.

Joseph Plateau never patented his invention and probably wasn't very interested in exploiting it, but he did design six discs for Ackermann & Co in London. These were published in July 1833 as Phantasmascope and later as Fantascope. Ackermann & Co soon published two more sets of six discs each, one designed by Thomas Talbot Bury and one by Thomas Mann Baynes.

In the meantime some other publishers had apparently been inspired by the first edition of Professor Stampfer's Stroboscopische Scheiben: Alphonse Giroux et Compagnie applied for a French import license on 28 May 1833 for 'Le Phénakisticope' and were granted one on 5 August 1833. They had a first set of 12 single sided discs available before the end of June 1833.[2] Before the end of December 1833 they released two more sets.

Joh. Val. Albert published "Die belebte Wunderscheibe" before 18 June 1833 in Frankfurt.[18] This version had uncut discs with pictures and a separate larger disc with round holes. The set of Die Belebte Wunderscheibe in Dick Balzer's collection[19] shows several discs with designs that are very similar to those of Stampfer and about half of them are also very similar to those of Giroux' first set. It is unclear where these early designs (other than Stampfer's) originated, but many of them would be repeated on many discs of many other publishers. It is unlikely that much of this copying was done with any licensing between companies or artists.

Joseph Plateau and Simon Stampfer both complained around July 1833 that the designs of the discs they had seen around (besides their own) were poorly executed and they did not want to be associated with them.

The phénakisticope became very popular and soon there were very many other publishers releasing discs with numerous names, including:

- Toover-schijf (by A. van Emden, Amsterdam, August 1833)

- McLean's Optical Illusions, or, Magic Panorama (London, 1833)

- Fores's Moving Panorama, or Optical Illusions (London, September 1833)

- The Phenakistiscope or Magic Disc (by Forrester & Nichol & John Dunn, September 1833)

- Motoscope, of wonderschijf (Amsterdam, September 1833)

- Soffe's Phantascopic Pantomime, or Magic Illusions (December 1833)

- Le Fantascope (by Dero-Becker, Belgium, December 1833)

- Le Phenakisticope (by Junin & Lazard, Paris, 1833?)

- The Phenakisticope, or Living Picture (by W. Soffe)

- Wallis's Wheel of Wonders (London, December 1834)

- The Laughingatus, or Magic Circle (by G.S. Tregear, circa 1835)

- Periphanoscop - oder Optisches Zauber-theater / ou Le Spectacle Magique / or The Magical Spectacle (by R.S. Siebenmann, Arau)

- Optische Zauber-Scheiben / Disques Magique (unknown origin, one set executed by Frederic Voigtlaender)

- Optische Belustigungen - Optical Amusements - Optic Amusements (unknown origin)

- Das Phorolyt oder die magische Doppelscheibe (by Purkyně & Pornatzki, Breslau, 1841)

- Fantasmascope. Tooneelen in den spiegel (K. Fuhri, The Hague, 1848)

- Kinesiskop (designed by Purkyně, published by Ferdinand Durst, Prague, 1861)

- The Magic Wheel (by J. Bradburn, U.S.A., 1864)

- L'Ékonoscope (by Pellerin & Cie, France, 1868)

- Pantinoscope (with Journal des Demoiselles, France, 1868)

- Magic Circle (by G. Ingram, circa 1870)

- Tableaux Animés - Nouveau Phénakistiscope (by Wattilaux, France, circa 1875)

- The Zoopraxiscope (by Muybridge, U.S.A., 1893)

- Prof. Zimmerman's Ludoscope (by Harbach & Co, Philadelphia, 1904)

After its commercial introduction by the Milton Bradley Company, the Zoetrope (patented in 1867) soon became the more popular animation device and consequently fewer phénakisticopes were produced.

Scientific use

The phénakisticope was invented through scientific research into optical illusions and published as such, but soon the device was marketed very successfully as an entertaining novelty toy. After the novelty wore off it became mostly regarded as a toy for children, but it still proved to be a useful demonstration tool for some scientists.

The Czech physiologist Jan Purkyně used his version, called Phorolyt, in lectures since 1837.[20] In 1861 one of the subjects he illustrated was the beating of a heart.[21]

German physicist Johann Heinrich Jakob Müller published a set of 8 discs depicting several wave motions (waves of sound, air, water, etcetera) with J.V. Albert in Frankfurt in 1846.[22]

The famous English pioneer of photographic motion studies Eadweard Muybridge built a phenakisticope projector for which he had his photographs rendered as contours on glass discs. The results were not always very scientific; he often edited his photographic sequences for aesthetic reasons and for the glass discs he sometimes even reworked images from multiple photographs into new combinations. An entertaining example is the sequence of a man somersaulting over a bull chased by a dog.[23] For only one disc he chose a photographic representation; the sequence of a running horse skeleton, which was probably to detailed to be painted on glass. This disc was most likely the very first time a stop motion technique was successfully applied. Muybridge first called his apparatus Zoogyroscope, but soon settled on the name Zoöpraxiscope. He used it in countless lectures on human and animal locomotion between 1880 and 1895.[24]

Today

The Special Honorary Joseph Plateau Award, a replica of Plateau's original phenakistiscope, is presented every year to a special guest of the Flanders International Film Festival whose achievements have earned a special and distinct place in the history of international film making.

See also

References

- ↑ Prince, Stephen (2010). Through the Looking Glass: Philosophical Toys and Digital Visual Effects (PDF). Projections. 4. Berghahn Journals. doi:10.3167/proj.2010.040203. ISSN 1934-9688.

- 1 2 "Le Figaro : journal littéraire : théâtre, critique, sciences, arts, moeurs, nouvelles, scandale, économie" (in French) (178). 27 June 1833. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ↑ "Phénakistiscope (boîte pour disque de) AP-95-1693" [Phenakistiscope (disk box) AP-95-1693] (in French). La Cinémathèque Française. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ↑ "Phénakistiscope (boîte, manche et disques de) AP-15-1265" [Phénakistiscope (box, sleeve and disk) AP-15-1265] (in French). La Cinémathèque Française. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ Plateau (1833). "Des Illusions d'optique sur lesquelles se fonde le petit appariel appelé récemment Phénakisticope" [Optical illusions that underlie the small device recently called Phénakisticope]. Annales de chimie et de physique (in French): 304. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Herbert, Stephen. "Phenakistoscope Part Two". www.stephenherbert.co.uk. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Herbert, Stephen. "Zoetrope 2". www.stephenherbert.co.uk. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ Herbert, Stephen. "Projection Phenakistoscope 1". www.stephenherbert.co.uk. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Correspondance mathématique et physique (in French). 4. Brussels: Garnier and Quetelet. 1828. p. 393.

- ↑ Correspondance mathématique et physique (in French). 6. Brussels: Garnier and Quetelet. 1830. p. 121.

- ↑ Correspondance mathématique et physique (in French). 7. Brussels: Garnier and Quetelet. 1832. p. 365.

- 1 2 Stampfer, Simon (1833). Die stroboscopischen Scheiben; oder, Optischen Zauberscheiben: Deren Theorie und wissenschaftliche anwendung, erklärt von dem Erfinder [The stroboscopic discs; or optical magic discs: Its theory and scientific application, explained by the inventor] (in German). Vienna and Leipzig: Trentsensky and Vieweg. p. 2.

- ↑ Poggendorff, Johann C. (1834). Annalen der Physik und Chemie [Annual of Physics and Chemistry] (in German). Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth.

- ↑ "Bulletin de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et Belles-Lettres de Bruxelles" (in French). III (1). Brussels: l'Académie Royale. 1836: 9–10.

- ↑ Roget, Peter Mark (1834). Bridgewater treatises on the power, wisdom, and goodness of God as manifested in the creation - Treatise V, Vol II. p. 524. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Carpenter, William (February 1868). "On the Zoetrope and its antecedents". The Student and Intellectual Observer of Science, Literature and Art. Groombridge and Sons: 439.

- ↑ "Phenakistiscope (disque de) AP-94-345" [Phenakistiscope (disk) AP-94-345] (in French). La Cinémathèque Française. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ↑ "Die belebte Wunderscheibe" [The animated wonder wheel]. Beilage zum Frankfurter Journal (in German). Frankfurt (164): 5. 16 June 1833.

- ↑ Balzer, Dick (2007). "Phenakistascopes". dickbalzer.com. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ↑ Uebersicht der Arbeiten und Veränderungen im Jahre 1841 [Overview of works and changes in the year 1841] (in German). Breslau. 1842. pp. 62–63.

- ↑ "Phenakistiscope (disque de) AP-94-374" [Phenakistiscope (disk) AP-94-374] (in French). La Cinémathèque Française. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ↑ "Anwendung der strboskopischen Scheibe zur Versinnlichung der Grundgesetze der Wellenlehre; von J.Muller, in Freiburg" [Application of stroboscopic disc for demonstration of the basic laws of wave theory; by J.Muller, in Freiburg]. Annalen der Physik und Chemie (in German). Leipzig: J. C. Poggendorff. 67: 271–272. 1846. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ↑ Herbert, Stephen (January 2010). "Muy Blog". ejmuybridge.wordpress.com. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Herbert, Stephen. "Compleat Eadweard Muybridge - Zoopraxiscope Story". www.stephenherbert.co.uk. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

External links

- Collection of simulated phenakistiscopes in action - Museum For The History Of Sciences

- Optisches Spielzeug oder wie die Bilder laufen lernten, German book by Georg Füsslin with many pictures of phenacistiscope games and discs

- The Richard Balzer Collection (animated gallery)

- An exhibit of similar optical toys, including the zoetrope (Laura Hayes and John Howard Wileman Exhibit of Optical Toys in the NCSSM)

- Some pictures - Example of the phenakistiscope

- Magic Wheel optical toy, 1864, in the Staten Island Historical Society Online Collections Database