Eadweard Muybridge

| Eadweard Muybridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Edward James Muggeridge 9 April 1830 Kingston upon Thames, England |

| Died |

8 May 1904 (aged 74) Kingston upon Thames, England |

| Resting place | Woking, Surrey, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Photography |

| Patron(s) | Leland Stanford |

Eadweard Muybridge (/ˌɛdwərd ˈmaɪbrɪdʒ/; 9 April 1830 – 8 May 1904, born Edward James Muggeridge) was an English photographer important for his pioneering work in photographic studies of motion, and early work in motion-picture projection. He adopted the name Eadweard Muybridge, believing it to be the original Anglo-Saxon form of his name.[1]

At age 20, he emigrated to America, first to New York, as a bookseller, and then to San Francisco. He returned to England in 1861, and took up professional photography, learning the wet-plate collodion process, and secured at least two British patents for his inventions.[2] He went back to San Francisco in 1867, and in 1868 his large photographs of Yosemite Valley made him world-famous. Today, Muybridge is known for his pioneering work on animal locomotion in 1877 and 1878, which used multiple cameras to capture motion in stop-motion photographs, and his zoopraxiscope, a device for projecting motion pictures that pre-dated the flexible perforated film strip used in cinematography.[3]

In 1874 he shot and killed Major Harry Larkyns, his wife's lover, but was acquitted in a jury trial on the grounds of justifiable homicide.[4] He travelled for more than a year in Central America on a photographic expedition in 1875.

In the 1880s, Muybridge entered a very productive period at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, producing over 100,000 images of animals and humans in motion, capturing what the human eye could not distinguish as separate movements. He spent much of his later years giving public lectures and demonstrations of his photography and early motion picture sequences, travelling back to England and Europe to publicise his work. He also edited and published compilations of his work, which greatly influenced visual artists and the developing fields of scientific and industrial photography. He returned to his native England permanently in 1894, and in 1904, the Kingston Museum, containing a collection of his equipment, was opened in his hometown.

Names

Edward James Muggeridge was born and raised in England. Muggeridge changed his name several times, starting with "Muggridge". In 1855, in the United States, he used the surname "Muygridge".[5]

After he returned from Britain to the United States in 1867, he used the surname "Muybridge". In addition, he used the pseudonym Helios (Titan of the sun) to sign many of his photographs. He also used this as the name of his studio and made it the middle name for his only son, Florado Helios Muybridge, born in 1874.[6]

While travelling on a photography expedition in the Spanish-speaking nations of Central America in 1875, the photographer advertised his works under the name "Eduardo Santiago Muybridge" in Guatemala.[7] After an 1882 trip to England, he changed the spelling of his first name to "Eadweard", the Old English form of his name. The spelling was probably derived from the spelling of King Edward's Christian name as shown on the plinth of the Kingston coronation stone, which had been re-erected in the town in 1850 100 yards from Muybridge's childhood family home. He used "Eadweard Muybridge" for the rest of his career,[5][8] but his gravestone carries his name as "Eadweard Maybridge".[9]

Early life and career

Muybridge was born in Kingston upon Thames,[10] in the county of Surrey in England, on 9 April 1830 to John and Susanna Muggeridge; he had three brothers. His father was a grain and coal merchant, with business spaces on the ground floor of their house adjacent to the River Thames at No.30 High Street, and the family living in the rooms above.[11] After his father died in 1843, his mother carried on the business. His cousin Norman Selfe who also grew up in Kingston upon Thames moved to Australia and, following a family tradition, became a renowned engineer.[12] His Great Grandparents were Robert Muggeridge and Hannah Charman who were the parents of John Muggeridge (1756 - 1819.) John and his siblings were Corn Merchants and in the City of London although all were born in Banstead, Surrey. Edwards younger brother George born in 1833 is found living with his Uncle Samuel in 1851 after the death of his Father in 1843 which establishes the lineage of Edward James Muggeridge.

Muybridge emigrated to the United States at the age of 20, arriving in New York City and later moving to San Francisco in 1855, a few years after California became a state, and while the city was still the "capital of the Gold Rush".[13] He started a career as a publisher's agent for the London Printing and Publishing Company, and as a bookseller. At the time, the city was booming, with 40 bookstores, nearly 60 hotels and a dozen photography studios.[14] Later in his life, he wrote about also having spent time in New Orleans and New York City during his early years in the United States.[15]

Serious accident and recuperation

By 1860, Muybridge was a successful bookseller. He left his bookshop in care of his brother, and prepared to sail to England to buy more antiquarian books. However, Muybridge missed the boat and instead left San Francisco in July 1860 to travel by stagecoach over the southern route to Saint Louis, by rail to New York City, then by ship to England.[2][16]

In central Texas, Muybridge suffered severe head injuries in a violent runaway stagecoach crash which injured every passenger on board, and killed one of them.[17][18] Muybridge was bodily ejected from the vehicle, and hit his head on a rock or other hard object. He was taken 150 miles (240 km) to Fort Smith, Arkansas, for treatment (his earliest memories post-accident were there), where he stayed three months, trying to recover from symptoms of double vision, confused thinking, impaired sense of taste and smell, and other problems. He next went to New York City, where he continued in treatment for nearly a year before being able to sail to England.

Arthur P. Shimamura, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, has speculated that Muybridge suffered substantial injuries to the orbitofrontal cortex that probably also extended into the anterior temporal lobes, which may have led to some of the emotional, eccentric behavior reported by friends in later years, as well as freeing his creativity from conventional social inhibitions. Today, there still is little effective treatment for this kind of injury.[2][19]

While recuperating in England and receiving treatment from Sir William Gull, Muybridge took up the new field of professional photography sometime between 1861 and 1866.[19] Muybridge later stated that he had changed his vocation at the suggestion of his physician.[2] He learned the wet-plate collodion process in England, and may have been influenced by some of the great English photographers of those years, such as Julia Margaret Cameron.[20][21][22] Also during this period, Muybridge secured at least two British patents for his inventions, including the design of a high speed electrical shutter and electro-timer, to be used alongside a battery of up to 24 cameras.[2]

%2C_Vernal_Fall%2C_400_Feet%2C_Valley_of_Yosemite_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Photographing the American West

Muybridge had left San Francisco in 1860, as a merchant but returned in 1867, as a professional photographer with highly proficient technical skills and an artist's eye. He became successful in photography focusing principally on landscape and architectural subjects. He converted a lightweight carriage into a portable darkroom to carry out his work.[20] His business cards also advertised his services for portraiture.[23] His stereographs, the popular format of the time, were sold by various galleries and photographic entrepreneurs (most notably the firm of Bradley & Rulofson) on Montgomery Street, San Francisco. Early in his new career, Muybridge was hired by Robert B. Woodward (1824–1879) to take extensive photos of his Woodward's Gardens, a combination amusement park, zoo, museum, and aquarium which opened in San Francisco in 1866.[24]

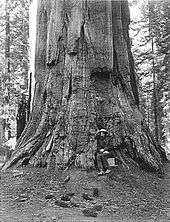

Muybridge established his reputation in 1867, with photos of the Yosemite Valley wilderness (some of which used the same scenes taken by his contemporary Carleton Watkins) and areas around San Francisco. Muybridge gained notice for his landscape photographs, which showed the grandeur and expansiveness of the West; if human figures were portrayed, they were dwarfed by their surroundings, as in Chinese landscape paintings. He signed and published his work under the pseudonym Helios, which he also used as the name of his studio.[25]

Muybridge took enormous physical risks to make his photographs, using a heavy view camera and stacks of glass plate negatives. A spectacular stereograph he published in 1872, shows him sitting casually on a projecting rock over the Yosemite Valley, with 2,000 feet (610 m) of empty space yawning below him.[2]

In 1868, Muybridge travelled to the newly acquired US territory of Alaska to photograph the Tlingit Native Americans, occasional Russian inhabitants, and dramatic landscapes for the US government.[26]:242 In 1871, the Lighthouse Board hired Muybridge to photograph lighthouses of the American west coast. From March to July, he travelled aboard the Lighthouse Tender Shubrick to document these structures.[27] In 1873, Muybridge was commissioned by the US Army to photograph the Modoc War against the Native Americans in northern California and Oregon. Many of his stereoscopic photos were published widely, and can still be found today.[26]:46

During the construction of the San Francisco Mint in 1870–1872, Muybridge made a sequence of images of the building's progress, using the power of time-lapse photography to document changes over time.[28]

As Muybridge's reputation as a photographer grew in the late 1800s, former California Governor Leland Stanford contacted him to help settle a bet. In 1878, Muybridge made a famous 13-part 360° photographic panorama of San Francisco, to be presented to the wife of Leland Stanford. Today, it can be viewed on the Internet as a seamlessly-spliced panorama, or as a QuickTime Virtual Reality (QTVR) panorama.[29]

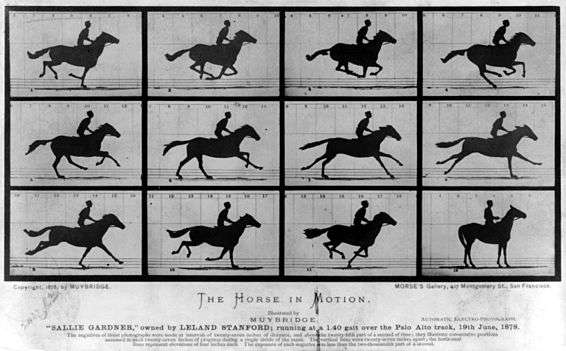

Stanford and horse gaits

In 1872, the former governor of California, Leland Stanford, a businessman and race-horse owner, hired Muybridge for some photographic studies. He had taken a position on a popularly debated question of the day — whether all four feet of a horse were off the ground at the same time while trotting. In 1872, Muybridge began experimenting with an array of 12 cameras photographing a galloping horse in a sequence of shots. His initial efforts seemed to prove that Stanford was right, but he didn’t have the process perfected. The same question had arisen about the actions of horses during a gallop. The human eye could not break down the action at the quick gaits of the trot and gallop. Up until this time, most artists painted horses at a trot with one foot always on the ground; and at a full gallop with the front legs extended forward and the hind legs extended to the rear, and all feet off the ground.[30] Stanford sided with the assertion of "unsupported transit" in the trot and gallop, and decided to have it proven scientifically. Stanford sought out Muybridge and hired him to settle the question.[31]

Between 1878 and 1884, Muybridge perfected his method of horses in motion, proving that they do have all four hooves off the ground during their running stride. In 1872, Muybridge settled Stanford's question with a single photographic negative showing his Standardbred trotting horse Occident airborne at the trot. This negative was lost, but the image survives through woodcuts made at the time (the technology for printed reproductions of photographs was still being developed). He later did additional studies, as well as improving his camera for quicker shutter speed and faster film emulsions. By 1878, spurred on by Stanford to expand the experiments, Muybridge had successfully photographed a horse at a trot;[32] lantern slides have survived of this later work.[33] Scientific American was among the publications at the time that carried reports of Muybridge's ground-breaking images.[33]

Stanford also wanted a study of the horse at a gallop. Muybridge planned to take a series of photographs on 15 June 1878, at Stanford's Palo Alto Stock Farm (now the campus of Stanford University). He placed numerous large glass-plate cameras in a line along the edge of the track; the shutter of each was triggered by a thread as the horse passed (in later studies he used a clockwork device to set off the shutters and capture the images).[34] The path was lined with cloth sheets to reflect as much light as possible. He copied the images in the form of silhouettes onto a disc to be viewed in a machine he had invented, which he called a "zoopraxiscope". This device was later regarded as an early movie projector, and the process as an intermediate stage toward motion pictures or cinematography.

The study is called Sallie Gardner at a Gallop or The Horse in Motion; it shows images of the horse with all feet off the ground. This did not take place when the horse's legs were extended to the front and back, as imagined by contemporary illustrators, but when its legs were collected beneath its body as it switched from "pulling" with the front legs to "pushing" with the back legs.[31]

Murder, acquittal and paternity

In 1872, Muybridge married 21-year-old Flora Shallcross Stone. In 1874, Muybridge discovered that a drama critic known as Major Harry Larkyns might have fathered Flora's seven-month-old son Florado.[31][35] On 17 October, Muybridge went to Calistoga to track down Larkyns. Upon finding him, Muybridge said, "Good evening, Major, my name is Muybridge and here's the answer to the letter you sent my wife", and shot him point-blank. Larkyns died that night, and Muybridge was arrested without protest and put in the Napa jail.[36]

Muybridge was tried for murder, and pleaded insanity due to a severe head injury suffered in the 1860 stagecoach accident. At least four long-time acquaintances testified under oath that the accident had dramatically changed Muybridge's personality, from genial and pleasant to unstable and erratic.[2] During the trial, Muybridge undercut his own insanity case by indicating that his actions were deliberate and premeditated, but he also showed impassive indifference and uncontrolled explosions of emotion.[2] The jury dismissed the insanity plea, but acquitted the photographer on the grounds of "justifiable homicide", disregarding the judge's instructions. The episode interrupted his photography studies, but not his relationship with Stanford, who had arranged for his criminal defense.[2]

Today, the court case and transcripts are important to historians and forensic neurologists, because of the sworn testimony from multiple witnesses regarding Muybridge's state of mind and past behaviour.[2] The American composer Philip Glass composed an opera, The Photographer, with a libretto based in part on court transcripts from the case.

Shortly after his acquittal in February 1875, Muybridge left the United States on a previously planned 9-month photography trip to Central America, as a "working exile".[31] By 1877, he had resumed work for Leland Stanford.

Flora petitioned for divorce, and was initially unsuccessful, but her second petition received a favourable ruling and an order for alimony in April 1875.[37] While Muybridge was in Central America, she died in July 1875.[2][37] She had placed their son, Florado Helios Muybridge (later nicknamed "Floddie" by friends), with a French couple. In 1876, Muybridge had the boy moved from a Catholic orphanage to a Protestant one and paid for his care,[37] but otherwise had little to do with him.

Photographs of Florado Muybridge as an adult show him to have strongly resembled Muybridge. Put to work on a ranch as a boy, he worked all his life as a ranch hand and gardener. In 1944, Florado was hit by a car in Sacramento and killed, at approximately the age of 70.[7]

Later motion studies

_animated_A.gif)

_animated_F.gif)

Muybridge often travelled back to England and Europe to publicise his work. The opening of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, and the development of steamships made travel much faster and less arduous than it was in 1860. On 13 March 1882 he lectured at the Royal Institution in London in front of a sell-out audience, which included members of the Royal Family, notably the future King Edward VII.[38] He displayed his photographs on screen and showed moving pictures projected by his zoopraxiscope.[38]

Muybridge and Stanford had a major falling-out concerning his research on equine locomotion. Stanford had asked his friend and horseman Dr. J. B. D. Stillman to write a book analysing The Horse in Motion, which was published in 1882.[33] Stillman used Muybridge's photos as the basis for his 100 illustrations, and the photographer's research for the analysis, but he gave Muybridge no prominent credit. The historian Phillip Prodger later suggested that Stanford considered Muybridge as just one of his employees, and not deserving of special recognition.[39]

However, as a result of Muybridge not being credited in the book, the Royal Society of Arts withdrew an offer to fund his stop-motion studies in photography, and refused to publish a paper he had submitted, accusing him of plagiarism.[2] Muybridge filed a lawsuit against Stanford to gain credit, but it was dismissed out of court.[31] However, Stillman's book did not sell as expected. Muybridge, looking elsewhere for funding, was more successful.[2] The Royal Society later invited Muybridge back to show his work.[31]

In the 1880s, the University of Pennsylvania sponsored Muybridge's research using banks of cameras to photograph people in a studio, and animals from the Philadelphia Zoo to study their movement. The human models, either entirely nude or very lightly clothed, were photographed against a measured grid background in a variety of action sequences, including walking up or down stairs, hammering on an anvil, carrying buckets of water, or throwing water over one another. Muybridge produced sequences showing farm, industrial, construction, and household work, military maneuvers, and everyday activities. He also photographed athletic activities such as baseball, cricket, boxing, wrestling, discus throwing, and a ballet dancer performing. Showing a single-minded dedication to scientific accuracy and artistic composition, Muybridge himself posed nude for some of the photographic sequences, such as one showing him swinging a miner's pick.[2][31]

Between 1883 and 1886, Muybridge made more than 100,000 images, working obsessively in Philadelphia under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania. During 1884, the painter Thomas Eakins briefly worked alongside him, to learn more about the application of photography to the study of human and animal motion. Eakins later favoured the use of multiple exposures superimposed on a single photographic negative to study motion more precisely, while Muybridge continued to use multiple cameras to produce separate images which could also be projected by his zoopraxiscope.[40] The vast majority of Muybridge's work at this time was done in a special sunlit outdoor studio, due to the bulky cameras and slow photographic emulsion speeds then available. Towards the end of this period, Muybridge spent much of his time selecting and editing his photos in preparation for publication.

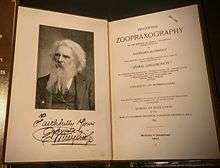

In 1887, the photos were published as a massive portfolio, with 781 plates comprising 20,000 of the photographs, in a groundbreaking collection titled Animal Locomotion: an Electro-Photographic Investigation of Connective Phases of Animal Movements.[41] Muybridge's work contributed substantially to developments in the science of biomechanics and the mechanics of athletics. Some of his books are still published today, and are used as references by artists, animators, and students of animal and human movement.[42]

Recent scholarship has noted that in his later work, Muybridge was influenced by, and in turn influenced the French photographer Étienne-Jules Marey. In 1881, Muybridge first visited Marey's studio in France and viewed stop-motion studies before returning to the US to further his own work in the same area.[43] Marey was a pioneer in producing multiple exposure sequential images using a rotary shutter in his so-called "Marey wheel" camera.

While Marey's scientific achievements in the realms of cardiology and aerodynamics (as well as pioneering work in photography and chronophotography) are indisputable, Muybridge's efforts were to some degree more artistic rather than scientific. As Muybridge explained, in some of his published sequences he had substituted images where original exposures had failed, in order to illustrate a representative movement (rather than producing a strictly scientific recording of a particular sequence).[44]

Today, similar setups of carefully timed multiple cameras are used in modern special effects photography but they have the opposite goal of capturing changing camera angles, with little or no movement of the subject. This is often dubbed "bullet time" photography.

After his work at the University of Pennsylvania, Muybridge travelled widely and gave numerous lectures and demonstrations of his still photography and primitive motion picture sequences. At the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, Muybridge presented a series of lectures on the "Science of Animal Locomotion" in the Zoopraxographical Hall, built specially for that purpose in the "Midway Plaisance" arm of the exposition. He used his zoopraxiscope to show his moving pictures to a paying public, making the Hall the first commercial movie theater.[45]

Retirement and death

Eadweard Muybridge returned to his native England in 1894, and continued to lecture extensively throughout Great Britain. He returned to the US once more, in 1896–1897, to settle financial affairs and to dispose of property related to his work at the University of Pennsylvania. He retained control of his negatives, which he used to publish two popular books of his work, Animals in Motion (1899) and The Human Figure in Motion (1901), both of which remain in print over a century later.[46]

Muybridge died on 8 May 1904 in Kingston upon Thames of prostate cancer at the home of his cousin Catherine Smith.[47] Muybridge was cremated, and his ashes were interred at Woking in Surrey. On his headstone, his name is misspelled "Eadweard Maybridge".[9][31]

In 2004, a British Film Institute commemorative plaque was installed on the outside wall of the former Smith house, at Park View, 2 Liverpool Road.[48] Many of his papers and collected artifacts were donated to the Kingston Library, and eventually passed to the Kingston Museum in his place of birth.

Influence on others

According to an exhibition at Tate Britain, "His influence has forever changed our understanding and interpretation of the world, and can be found in many diverse fields, from Marcel Duchamp's painting Nude Descending a Staircase and countless works by Francis Bacon, to the blockbuster film The Matrix and Philip Glass's opera The Photographer."[49]

- Étienne-Jules Marey — recorded the first series of live action photos with a single camera by a method of chronophotography; influenced and was influenced by Muybridge's work

- Thomas Eakins — American artist who worked with and continued Muybridge's motion studies, and incorporated the findings into his own artwork

- William Dickson — credited as inventor of the motion picture camera

- Thomas Edison — developed and owned patents for motion picture cameras

- Marcel Duchamp — artist, painted Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, inspired by multiple-exposure photography

- Harold Eugene Edgerton — pioneered stroboscopic and high speed photography and film, producing an Oscar-winning short movie and many striking photographic sequences

- Francis Bacon — painted from Muybridge photographs

- John Gaeta — used the principles of Muybridge photography to create the bullet time slow-motion technique of the 1999 movie The Matrix.[50]

- Steven Pippin — so-called Young British Artist who converted a row of laundromat washing machines into sequential cameras in the style of Muybridge

- Wayne McGregor — UK choreographer collaborated with composer Mark-Anthony Turnage and artist Mark Wallinger on a piece entitled "Undance", inspired by Muybridge's "action verbs"[51]

Exhibitions and collections

A collection of Muybridge's equipment, including his original biunial slide lantern[52] and zoopraxiscope projector, can be viewed at the Kingston Museum in Kingston upon Thames, South West London. The University of Pennsylvania Archives in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, hold a large collection of Muybridge's photographs, equipment, and correspondence.[53] The Stanford University Libraries and the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University also maintain a large collection of Muybridge's photographs, glass plate negatives, and some equipment including a functioning zoopraxiscope.[54]

In 1991, the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, hosted a major exhibition of Muybridge's work, plus the works of many other artists who had been influenced by him. The show later traveled to other venues and a book-length exhibition catalogue was also published.[55] The Addison Gallery has significant holdings of Muybridge's photographic work.[56]

In 2000–2001, the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History presented the exhibition Freeze Frame: Eadweard Muybridge's Photography of Motion, plus an online virtual exhibit.[57]

From 10 April through 18 July 2010, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, mounted a major retrospective of Muybridge's work entitled Helios: Eadweard Muybridge in a Time of Change. The exhibit received favourable reviews from major publications including The New York Times.[58] The exhibition traveled in autumn 2010 to the Tate Britain, Millbank, London,[59] and also appeared at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA).

An exhibition of important items bequeathed by Muybridge to his birthplace of Kingston upon Thames, entitled Muybridge Revolutions, opened at the Kingston Museum on 18 September 2010 (exactly a century since the first Muybridge exhibition at the Museum) and ran until 12 February 2011.[60] The full collection is held by the Museum and Archives.[61]

Bibliography

- Muybridge's Complete Human and Animal Locomotion, Vol. I: All 781 Plates from the 1887 "Animal Locomotion" (1979) Dover Publications ISBN 9780486237923[62]

- Descriptive Zoopraxography, or the Science of Animal Locomotion Made Popular. Library of Alexandria. 1893. ISBN 9781465542977.

Legacy and representation in other media

- The main campus site of Kingston University has a building named after Muybridge.[63]

- Many of Muybridge's photographic sequences have been published since the 1950s as artists' reference books. Cartoon animators often use his photos as a reference when drawing their characters in motion.[42][64][65]

- In the 50s TV series Death Valley Days, hosted by Ronald Reagan, the story of Eadweard Muybridge's invention of the zoopraxiscope was told in the episode titled "The $25,000 Wager"

- Jim Morrison makes a reference to Muybridge in his poetry book The Lords (1969), suggesting that "Muybridge derived his animal subjects from the Philadelphia Zoological Garden, male performers from the University".[66]

- The filmmaker Thom Andersen made a 1974 documentary titled Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer, describing his life and work.

- The composer Philip Glass's opera The Photographer (1982) is based on Muybridge's murder trial, with a libretto including text from the court transcript.

- In 1985, the music video for Larry Gowan's single "(You're a) Strange Animal" prominently featured animation rotoscoped from Muybridge's work. In 1986, a galloping horse sequence was used in the background of the John Farnham music video for the song "Pressure Down".

- Muybridge is a central figure in John Edgar Wideman's 1987 novel Reuben.

- Muybridge's work figures prominently in Laird Barron's tale of Lovecraftian horror, "Hand of Glory".

- Since 1991, the company Optical Toys has published Muybridge sequences in the form of movie flipbooks.

- The video for Scottish singer Jimmy Somerville's song, "Coming," featured in the 1992 film "Orlando," features dozens of Muybridge's motion study photographs.

- In 1993, the music video for U2's "Lemon", directed by Mark Neale, was filmed in black and white with a grid-like background as a tribute to Eadweard Muybridge.

- The play Studies in Motion: The Hauntings of Eadweard Muybridge (2006) was a co-production between Vancouver's Electric Company Theatre and the University of British Columbia Theatre. While blending fiction with fact, it conveys Muybridge's obsession with cataloguing animal motion. The production started touring in 2010. In 2015, it would be adapted into a feature film.

- The Canadian poet Rob Winger wrote Muybridge's Horse: A Poem in Three Phases (2007). The long poem won the CBC Literary Award for Poetry and was nominated for the Governor General's Award for Literature, the Trillium Book Award for Poetry, and the Ottawa Book Award. It expressed his life and obsessions in a "poetic-photographic" style.

- To accompany the 2010 Tate exhibition, the BBC commissioned a TV programme, "The Weird World of Eadweard Muybridge", as part of Imagine, the arts series presented by Alan Yentob.[67]

- On 9 April 2012, the 182nd anniversary of his birth, a Google Doodle honoured Muybridge with an animation based on the photographs of the horse in motion.[68]

- Writer Josh Epstein and director Kyle Rideout made the feature film Eadweard (2015), starring Michael Eklund and Sara Canning. The film tells the story of Eadweard Muybridge's motion experiments, social effects with consideration to the morality of photographing nude figures in motion, his work with sanitarium patients, and his death in a duel.[69]

- Muybridge appears as a character in Brian Catling's 2012 novel, The Vorrh, where events from his life are blended into the fantasy narrative.

- Czech theatre company Laterna Magika has introduced an original play based on Maybridge's life in 2014.[70] The play follows his life and combines dancing and speech with multimedia created from Muybridge's works.

See also

References

- ↑ "If anything, the surname Muggeridge actually derives from a place in Devon, Mogridge, in turn taking its name from one Mogga who held a ridge there. Edward, on the other hand, was indeed spelled Eadweard in Old English." Adrian Room, Naming Names: Stories of Pseudonyms and Name Changes, with a Who's Who, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981, p. 125.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Shimamura, Arthur P. (2002). "Muybridge in Motion: Travels in Art, Psychology, and Neurology" (PDF). History of Photography. 26 (4): 341–350.

- ↑ "Eadweard Muybridge (British photographer)". Britannica. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

English photographer important for his pioneering work in photographic studies of motion and in motion-picture projection.

- ↑ Riesz, Megan. "Did Eadweard J. Muybridge get away with murder?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- 1 2 Solnit 2003, p. 7

- ↑ "Exhibition notes", Muybridge Exhibition at Tate Britain, January 2011.

- 1 2 Solnit 2003, p. 148

- ↑ Paul Hill Eadweard Muybridge Phaidon, 2001

- 1 2 Adam, (ed.), Hans Christian (2010). Eadweard Muybridge, the human and animal locomotion photographs (1. Aufl. ed.). Köln: Taschen. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-8365-0941-1.

- ↑ "Eadweard Muybridge". Kingston Council. Kingston upon Thames Council. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ↑ The building today bears a commemorative plaque marking it as Muybridge's childhood home.

- ↑ Anderson, Maybanke (2001). "My Sprig of Rosemary". In Jan Roberts & Beverley Kingston. Maybanke, a woman's voice: the collected work of Maybanke Selfe - Wolstenholme - Anderson, 1845–1927. Avalon Beach, N.S.W.: Ruskin Rowe Press. ISBN 0-9587095-3-X. pp. 24–25

- ↑ Solnit 2003, p. 29

- ↑ Solnit 2003, p. 30

- ↑ Solnit 2003, p. 27-28

- ↑ Brookman 2010, p. 29

- ↑ Solnit 2003, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Brian Clegg (2007). The Man Who Stopped Time: The Illuminating Story of Eadweard Muybridge : Pioneer Photographer, Father of the Motion Picture, Murderer, p. 90.

- 1 2 Solnit 2003, p. 39

- 1 2 Solnit 2003, p. 40

- ↑ Eadweard Muybridge. Muybridge's Complete Human and Animal Locomotion: All 781 Plates from the 1887 Animal Locomotion, Courier Dover Publications, 1979

- ↑ Lance Day, Ian McNeil. Biographical Dictionary of the History of Technology, p. 884. Routledge, 2003.

- ↑ Helios: Eadweard Muybridge in a Time of Change. Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.ashington. 10 April – 18 July 2010. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012.

- ↑ Peter Hartlaub (2012-10-30). "Peter Hartlaub, "Woodward's Gardens Comes to Life in New Book", San Francisco Chronicle (October 30, 2012)". Sfgate.com. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

- ↑ James Kaiser (2007) Yosemite, The Complete Guide: Yosemite National Park, p. 104

- 1 2 Paula Fleming and Judith Lusky, The North American Indians in Early Photographs, Dorset Press, 1988, (source: Ralph W. Andrews, 1964 and David Mattison, 1985)

- ↑ Bowdoin, Jeffrey. "West Coast Lighthouses of the 19th Century". U.S. Coast Guard History Program. United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ↑ Bullough, William A. (Spring–Summer 1989). "Eadweard Muybridge and the Old San Francisco Mint: Archival Photographs as Historical Documents". California History. 68 (1/2): 2–13. doi:10.2307/25158510. JSTOR 25158510.

- ↑ "Archive – City Views of San Francisco". Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum. CPRR.org. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- ↑ "Eadweard Muybridge and His Influence on Horse Art". Your-guide-to-gifts-for-horse-lovers.com. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mitchell Leslie (May–June 2001). "The Man Who Stopped Time". Stanford Magazine. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Williams, Alan Larson (1992) Republic of Images: A History of French Filmmaking, Harvard University Press

- 1 2 3 "Capturing the Moment", p. 2, Freeze Frame: Eadward Muybridge's Photography of Motion, 7 October 2000 – 15 March 2001, National Museum of American History, accessed 9 April 2012

- ↑ Muybridge, Eadweard; Mozley, Anita Ventura (foreword) (1887). Muybridge's Complete Human and Animal Locomotion: All 781 Plates from the 1887 Animal Locomotion. Courier Dover Publications. p. xvii. ISBN 978-0-486-23792-3. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ↑ He had discovered letters between them, one of which included a photo of the child with the caption "Little Harry". The (Washington, D.C.) Examiner, 17 October 2012, p. 8.

- ↑ Haas, Robert Bartlett (1976). Muybridge: Man in Motion. Oakland, Calif.: University of California. ISBN 978-0-52002-464-9.

- 1 2 3 Brookman 2010, p. 69

- 1 2 Brian Clegg The Man Who Stopped Time: The Illuminating Story of Eadweard Muybridge : Pioneer Photographer, Father of the Motion Picture, Murderer, Joseph Henry Press, 2007

- ↑ John Sanford (12 February 2003). "Cantor exhibit showcases motion-study photography". Stanford Report. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ↑ Brookman 2010, p. 93

- ↑ Selected Items from the Eadweard Muybridge Collection (University of Pennsylvania Archives and Records Center) "The Eadweard Muybridge Collection at the University of Pennsylvania Archives contains 702 of the 784 plates in his Animal Locomotion study"

- 1 2 "Eadweard Muybridge" (PDF). Saylor.org. p. 4. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ Brookman 2010, p. 91

- ↑ Adam, (ed.), Hans Christian (2010). Eadweard Muybridge, the human and animal locomotion photographs (1. Aufl. ed.). Köln: Taschen. p. 14. ISBN 978-3-8365-0941-1.

- ↑ Clegg, Brian (2007). The Man Who Stopped Time. Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 0-309-10112-3.

- ↑ Brookman 2010, p. 100

- ↑ Brookman 2010, p. 101

- ↑ Braun, Marta; Herbert, Stephen; Hill, Paul; McCormack, Anne (2004). Herbert, Stephen, ed. Eadweard Muybridge: The Kingston Museum Bequest. The Projection Box. ISBN 1-903000-07-6.

- ↑ Eadweard Muybridge. Tate. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ "Muybridge at Tate Britain". Tate.org.uk. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ Thomas, Rebecca (25 November 2011). "McGregor, Turnage and Wallinger unite for dance debut". BBC News. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ↑ A form of lantern which can project two images at once, used to produce fade and dissolve effects.

- ↑ "Eadweard Muybridge, 1830 – 1904, Collection, 1870 – 1981". Archives.upenn.edu. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ↑ Phillip Prodger, "Time Stands Still: Muybridge and the Instantaneous Photography Movement" (Oxford University Press and Stanford University, 2003). ISBN 0195149645

- ↑ Sheldon, James L.; Jock Reynolds (1991). Motion and Document—Sequence and Time: Eadweard Muybridge and Contemporary American Photography. Andover, Massachusetts: Addison Gallery of American Art.

- ↑ "About the Collection". Addison Gallery of American Art (website). Philips Academy, Andover. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ↑ "Freeze Frame: Eadweard Muybridge's Photography of Motion — online exhibit". Virtual National Museum of American History (website). National Museum of American History. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ↑ Karen Rosenberg (26 April 2010). "A Man Who Stopped Time to Set It in Motion Again". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Eadweard Muybridge at Tate Britain, 8 September 2010 – 16 January 2011". Tate.org.uk. Retrieved 9 April 2012. "This exhibition brings together the full range of his art for the first time, and explores the ways in which Muybridge created and honed his remarkable images, which continue to resonate with artists today. Highlights include a seventeen foot panorama of San Francisco and recreations of the zoopraxiscope in action."

- ↑ "Kingston Museum – Muybridge Revolutions". Muybridgeinkingston.com. Retrieved 9 April 2012. "This important collection includes Muybridge's original Zoöpraxiscope machine and 68 of only 71 glass Zoöpraxiscope discs known to exist worldwide. In addition, the archive holds many personalised lantern slides, hundreds of collotype prints, rare early albums, Muybridge's own scrapbook in which he charts his entire career, a copy of his epic San Franscisco Panorama; and many other items that make the Kingston Muybridge bequest a collection of major international significance."

- ↑ The Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames Muybridge Collection Archived 18 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Muybridge's Complete Human and Animal Locomotion, Vol. I: All 781 Plates from the 1887 "Animal Locomotion"". Goodreads. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ↑ "Eadweard Muybridge and main buildings". Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ↑ "Books for figure drawing models and artists (reference books)". Artmodeltips.com, A website for life models and figurative artists. Artmodeltips.com. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ Eadweard Muybridge (2007). Muybridge's Human Figure in Motion. Dover Publications, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-486-99771-1. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ "The Lords, 11th Paperback Edition edition (October 15, 1971)". Touchstone. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ↑ "Times. Imagine: Episode 3, The Weird World of Eadweard Muybrige". Radiotimes.com. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

- ↑ Eadweard J Muybridge celebrated in a Google doodle The Guardian, 9 April 2012

- ↑ "Eadweard (2015)". imdb.com. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- ↑ "Human Locomotion Theatre in Prague: The Story of Eadweard Muybridge". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

Sources

- Brookman, Philip; Braun, Marta; Keller, Corey; Solnit, Rebecca (2010). Brookman, Philip, ed. Helios: Eadweard Muybridge in a Time of Change. Göttingen, Germany: Steidl. ISBN 978-3-86521-926-8.

- Hendricks, Gordon (2001). Eadweard Muybridge: The Father of the Motion Picture. Mineola, New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-48641-535-2.

- Mozley, Anita Ventura, ed. (1972). Eadweard Muybridge: The Stanford Years 1872 - 1882. Contributions by Robert Bartlett Haas. Berkeley, Calif.: Stanford Univ., Department of Art.

- Solnit, Rebecca (2003). River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-670-03176-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Eadweard Muybridge at the Internet Movie Database

- Article on discovered Muybridge photos, March 2012

- Time Stands Still, exhibit on Eadweard Muybridge and contemporaries, February–May 2003, Cantor Center, Stanford University

- Eadweard Muybridge's Animal Locomotion, via Boston Public Library's Flickr collections

- Eadweard Muybridge at Who's Who of Victorian Cinema

- The Eadweard Muybridge Online Archive, access to most of Muybridge's motion studies, at printable resolutions, along with a growing number of animations.

- "Tesseract", 20-Min experimental film expressing Eadweard Muybridge's obsession with time and its images at the turn of the century.

- Eadweard Muybridge, Valley of the Yosemite, Sierra Nevada Mountains, and Mariposa Grove of Mammoth Trees, 1872, finding aid and online photo collection, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

- Eadweard Muybridge, Stereographic Views of San Francisco Bay Area Locations, ca. 1865-ca. 1879, finding aid and online photo collection, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

- Era of exploration : the rise of landscape photography in the American West, 1860-1885, fully digitized text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art libraries

- Muybridge, 1872, Yosemite American Indian Life, The Hive

- "The Muybridge Collection", Kingston Museum, Kingston upon Thames, Surrey

- Muybridge's 11-volume Animal Locomotion Studies and similar publications by E.-J. Marey, The University of South Florida Tampa Library's Special Collections Department

- Freezing Time, Film Website, the life of Muybridge, directed by Andy Serkis and written by Keith Stern

- "Eadweard Muybridge". Photography. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- Eadweard Muybridge stereoscopic photographs of the Modoc War, via Calisphere, California Digital Library, University of California, Berkeley

- Human and Animal Locomotion, via SC Digital Library, University of Southern California.

- Teacher's Guide: Eadweard Muybridge, Harold Edgerton, and Beyond: A Study of Motion and Time, 2-part introduction to the work of Muybridge and Edgerton, for high school level, Addison Museum

- The short film It Started With Muybridge (1965) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- David Levy, "Muybridge and the Movies", Early American Cinema

- Carola Unterberger-Probst, Animation of the first moving pictures in film history, Rhizome

- Burns, Paul. The History of the Discovery of Cinematography: An Illustrated Chronology, Pre-cinema history

- The Compleat Eadweard Muybridge, extensive illustrated bibliography and links

- Lone Mountain College Collection of Stereographs by Eadweard Muybridge, 1867–1880 at The Bancroft Library

- Boston Athenæum: Central America Illustrated by Muybridge. Digital Collection.

- Works by Eadweard Muybridge at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Eadweard Muybridge at Internet Archive

- Collections search for the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University including the Cantor's Muybridge holdings