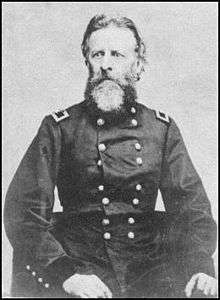

Philip St. George Cooke

| Philip St. George Cooke | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

June 13, 1809 Leesburg, Virginia |

| Died |

March 20, 1895 (aged 85) Detroit, Michigan |

| Place of burial | Elmwood Cemetery, Detroit, Michigan |

| Allegiance |

United States of America Union |

| Service/branch |

United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1827–1873 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands held |

Mormon Battalion 2nd Cavalry Regiment Department of the Platte |

| Battles/wars |

Black Hawk War Bleeding Kansas |

Philip St. George Cooke (June 13, 1809 – March 20, 1895) was a career United States Army cavalry officer who served as a Union General in the American Civil War. He is noted for his authorship of an Army cavalry manual, and is sometimes called the "Father of the U.S. Cavalry." His service in the Civil War was significant, but was eclipsed in prominence by the contributions made by his famous son in law, J.E.B. Stuart, to the Confederate States Army.

Early life

Cooke was born in Leesburg, Virginia, June 13, 1809.[1] He graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1827 and was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the infantry. He served at a variety of installations in the American West and in the Black Hawk War. In 1833 he was promoted to first lieutenant in the newly formed 1st U.S. Dragoons.

Cooke went on numerous trips of exploration into the Far West with the Dragoons. As Captain in command of 200 Dragoons, he disarmed and arrested Colonel Snively's Republic of Texas company of about 100 men, who were attempting to disrupt trade along the Santa Fe Trail, in what was described as the Second Texas Santa Fe Expedition.[2] During the Mexican-American War he led the Mormon Battalion from Santa Fe to California, receiving a brevet promotion to lieutenant colonel for his service in California. In the 2nd U.S. Dragoons he defeated the Jicarilla Apache in Ojo Caliente, New Mexico in 1854, was in the 1855 Battle of Ash Hollow against the Sioux, and was sent to keep the peace in Bleeding Kansas in 1856 – 1857. Acquainted with Brigham Young, Cooke took part in the Utah expedition of 1857–58, after which he was promoted to colonel and assigned command of the 2nd U.S. Dragoons. He was an observer for the U.S. Army in the Crimean War, and commanded the Department of Utah from 1860 until 1861.

The issue of secession deeply divided Cooke's family. Cooke himself remained loyal to the Union, but his son, John Rogers Cooke, became an infantry brigade commander in the Army of Northern Virginia. J.E.B. Stuart, the famous Confederate cavalry commander, was Cooke's son-in-law. Cooke and Stuart never spoke again, Stuart saying, "He will regret it only once, and that will be continually."[3]

Civil War

At the start of the American Civil War, the U.S. Army had five mounted regiments. Cooke commanded the 2nd Dragoons, which was redesignated the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. As they prepared to ride into their first battles, they had the potential opportunity to learn from the two-volume manual on cavalry tactics written by Cooke in 1858, but not published until 1862. It was a controversial work at the time and the War Department chose not to make it the basis for official doctrine. Cooke espoused the value of mounted attacks as the primary purpose for cavalry forces; others, more sensibly, realized that the emergence of the rifled musket as an infantry weapon made the classic cavalry charge essentially obsolete and recommended a mission emphasis on reconnaissance and screening. Even those who agreed that cavalry charges retained some value found reasons to disagree with Cooke. A prominent theory of cavalry charges at the time, endorsed by future generals Henry W. Halleck and George B. McClellan, was that the cavalry should be deployed in double ranks (a regiment would deploy in two lines of five companies each), which would increase the shock effect of the charge by providing an immediate follow-up attack. Cooke's manual called for a single-rank formation in which a battalion of four companies would form a single line and two squadrons of two companies each would cover the flanks. A third battalion would be placed in reserve a few hundred yards to the rear. Cook believed that the double-rank offensive promoted disorder of the horses in the ranks and would be difficult to control.

Cooke was appointed brigadier general, U.S. Army, on November 21, 1861, to rank from November 12, 1861.[4] President Abraham Lincoln nominated Cooke for the appointment on December 21, 1861 and the U.S. Senate confirmed it on March 7, 1862.[4] He initially commanded a brigade of regular army cavalry within the defenses of Washington, D.C. For the Peninsula Campaign, he was selected by McClellan to command the Cavalry Reserve, a division-sized force, of the Army of the Potomac. When Confederate forces evacuated the city of Yorktown, Cooke was sent along with Major General George Stoneman in pursuit and his cavalry was roughed up in an assault ordered by Stoneman against Fort Magruder. He saw subsequent action at the battles of Williamsburg, Gaines' Mill, and White Oak Swamp. Cooke ordered an ill-fated charge of the 5th U.S. Cavalry at Gaines' Mill during the Seven Days Battles, sacrificing nearly an entire regiment of regulars.

After the Peninsula, Cooke left active field service. One proximate reason was the embarrassment he suffered when his son-in-law, Jeb Stuart, humiliated the Union cavalry by completely encircling the Army of the Potomac in his celebrated raid. Cooke served on boards of court-martial, commanded the District of Baton Rouge, and was superintendent of Army recruiting for the Adjutant General's office. On July 17, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Cooke for appointment to the brevet grade of major general in the regular army, to rank from March 13, 1865, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment on July 23, 1866.[5]

Postbellum life

Cooke commanded the Department of the Platte from 1866 to 1867, the Department of the Cumberland from 1869 to 1870, and the Department of the Lakes. He retired from the Army with almost 50 years service on October 29, 1873 as a brigadier general.[6]

Cooke was a member of the Michigan Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States.

Cooke is the author of a variety of memoirs of his service: Notes of a Military Reconnaissance, from Fort Leavenworth, in Missouri, to San Diego, in California (1848), Scenes and Adventures in the Army: or, Romance of Military Life (1857), Cavalry Tactics (1862), Handy Book for United States Cavalry (1863), and The Conquest of New Mexico and California (1878).

Cooke died in Detroit, Michigan, and is buried there in Elmwood Cemetery. Camp Cooke, an Army camp in Santa Barbara County, California, was named for him. The spot is now occupied by Vandenberg Air Force Base.

Legacy

Camp Cooke (1866–1870), the first military post in the Montana Territory, was named in honor of Phillip St. George Cooke while he was the commander of the Department of the Platte which included the Montana Territory.

Camp Cooke (1941–1953) was the name given to the military post near Lompoc California. It was deactivated from 1953 to 1957, at which time it was activated as Cooke Air Force Base (1957–1958) but was officially renamed Vandenberg Air Force Base in 1958. Camp Cooke and Cooke Air Force Base in California were named in honor of Philip St. George Cooke.[7]

Historians theorize that St. George, Utah was named after Phillip St. George Cooke.[8] During the period of 1857 to 1861 Col. Cooke was in Utah. He was a close personal friend of Brigham Young and donated equipment and wagons to the settlement of the southern part of Utah.

See also

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)

- Cavalry in the American Civil War

- Camp Cooke

- Camp Cooke (Montana)

Notes

- ↑ Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3. p. 183

- ↑ Gregg, Josiah. Commerce of the Prairies: or, The journal of a Santa Fé trader, 1831–1839. A. H. Clark, 1905. p. 227-233

- ↑ Thomas, p. 95.

- 1 2 Eicher, 2001, p. 716

- ↑ Eicher, 2001, p. 706

- ↑ Eicher, 2001, p. 184

- ↑ Camp Cooke

- ↑ City of St. George

References

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Longacre, Edward G. Lincoln's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000. ISBN 0-8117-1049-1.

- Thomas, Emory M. Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986. ISBN 0-8061-3193-4.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

External links

- Online text of Cooke's cavalry manual at the Wayback Machine (archived March 12, 2008)

- Scenes and Adventures

- Elmwood Cemetery Biography on Cooke

- Philip St. George Cooke in Union or Secession: Virginians Decide at the Library of Virginia

- Philip St. George Cook e in Encyclopedia Virginia