Phoenicianism

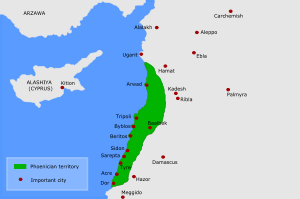

Phoenicianism is a form of Lebanese nationalism, first adopted by Lebanese Christians, primarily Maronites , at the time of the creation of Greater Lebanon.[1]

It promotes the view that Lebanese people, or sometimes exclusively just Lebanese Christians, are not Arabs and that the Lebanese speak a distinct language and have their own culture, separate from that of the surrounding Middle Eastern countries. Supporters of this theory of Lebanese ethnogenesis maintain that the Lebanese are descended from Phoenicians and are not Arabs. Some also maintain that Levantine Arabic is not an Arabic variety, rather a variation of Neo-Aramaic, but has become a distinctly separate language.

Other theories of Maronite origin suggest Aramean origin, ancient Assyrian origin, Arab Bedouin origin or Mardaite origin.[2]

Phoenicianism parallels other Middle Eastern Christian ancient continuity theories, such as Nestorian Assyrian continuity and Coptic Pharaonism.[3] These are contrasted with Arabism and pan-Arabism.

Position

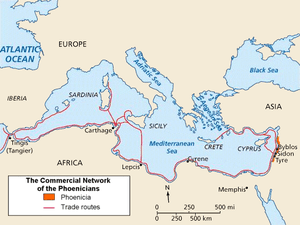

Proponents claim that the land of Lebanon has been inhabited uninterruptedly since Phoenician times, and that the current population descends from the original population, with some admixture due to immigration over the centuries. They argue that Arabization merely represented a shift to the Arabic language as the vernacular of the Lebanese people, and that, according to them, no actual shift of ethnic identity, much less ancestral origins, occurred. Historians have noted that the inhabitants of the Lebanese mountains continued to be called Phoenicians well into the first centuries AD, and that demographic continuity is known to have existed until the Islamic invasions.[4] It has also been noted that pan-Arabism first arose in the 20th Century, that the Lebanese delegation to the peace conference after World War I was unanimously opposed to including Lebanon in the Arab zone, and that such opposition was also present in Syria.[5] In light of this "old controversy about identity",[6] some Lebanese prefer to see Lebanon, Lebanese culture and themselves as part of "Mediterranean" and "Canaanite" civilization, in a concession to Lebanon's various layers of heritage, both indigenous, foreign non-Arab, and Arab. Some consider addressing all Lebanese as Arabs somewhat insensitive, and prefer to call them Lebanese as a sign of respect of Lebanon's long non-Arabic past.

Language

Arabic

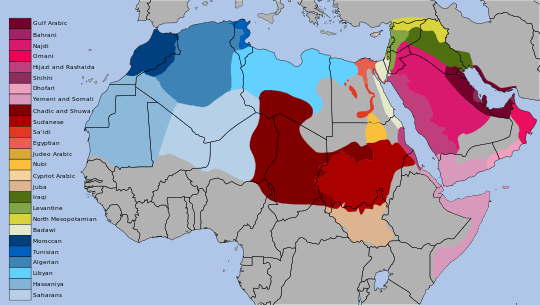

The Arabic language is considered to exist in multiple forms: formal Arabic, commonly known as Modern Standard Arabic (a modern incarnation of Koranic or Classical Arabic), which is used in written documents and formal contexts; and dialectal variants, numbering some thirty vernacular speech forms, used in day-to-day contexts, and varying widely from country to country. The one spoken in Lebanon is called "Lebanese Arabic" or simply "Lebanese", and it is a type of Levantine Arabic, which, together with Mesopotamian Arabic, is classed by matter of convenience as a type of Northern Arabic. The point of controversy between Phoenicianists and their opponents lies in whether the differences between the Arabic varieties are sufficient to consider them separate languages. The former cite Prof. Wheeler Thackston of Harvard: "the languages the 'Arabs' grow up speaking at home, are as different from each other and from Arabic itself, as Latin is different from English."[7]

There is a lack of consensus on the distinction between lingual taxa such as languages and dialects. A neutral term in linguistics is "language variety" (a.k.a. "lect"), which can be anything from a language or a family of languages to a dialect or a continuum of dialects, and beyond. The most common, and most purely linguistic, criterion is that of mutual intelligibility: two varieties are said to be dialects of the same language if being a speaker of one variety confers sufficient knowledge to understand and be understood by a speaker of the other; otherwise, they are said to be different languages. By this criterion, the variety commonly known as the Arabic language is indeed considered by linguists to be not a single language but a family of several languages, each with its own dialects.[8] For political reasons, it is common in the Arabic-speaking world (a.k.a. the Arab world) for speakers of different Arabic varieties to assert that they all speak a single language, despite significant issues of mutual incomprehensibility among differing spoken versions.[9]

Aramaic language

For nearly a thousand years before the spread of the Arab-Muslim conquests in the 7th century AD, Aramaic was the lingua franca and main spoken language in the Fertile Crescent.[10] Among the Maronites, traditionally, neo-Aramaic had been the spoken language up to the 17th century, when Arabic took its place, while classical Syriac remained in use only for liturgical purposes, as a sacred language (also considered as such in Judaism, alongside Hebrew). Today the vast majority of people in Lebanon speak Lebanese Arabic as their first language. More recently, some effort has been put into revitalizing Aramaic as an everyday spoken language in some ethnic Lebanese communities.[11] Also, the modern type of Aramaic has an estimated 550,000 native speakers, mainly among Assyrians,[12] a Christian ethnoreligious group related to but distinct from the Maronites of Lebanon.

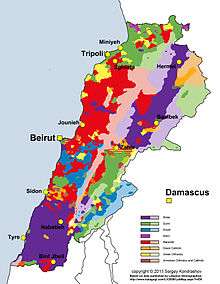

Religion

Followers of any religion can be Phoenicianists, including Lebanese Muslims (Shia and Sunni). However, because of how closely religious and ethnic identities are intertwined in Lebanon, Phoenicianism is especially common among those Lebanese people who adhere to Christianity, the main religion of most of the Lebanese before the expansion of the Arab-Muslim conquests from the Arabian Peninsula.Template:Cnh

Representation in the government

Among political parties professing Phoenicianism is the Kataeb Party,[13] a Lebanese nationalist party in the March 14 Alliance. It is officially secular, but its electorate is primarily Christian.

Differing views and criticism

The Dutch university professor Leonard C. Biegel, in his 1972 book Minorities in the Middle East: Their significance as political factor in the Arab World, coined the term Neo-Shu'ubiyya to name the modern attempts of alternative non-Arab nationalisms in the Middle East, e.g. Aramaeanism, Assyrianism, Greater Syrian nationalism, Kurdish nationalism, Berberism, Pharaonism, Phoenicianism.[14]

Historian Kamal Salibi, a Lebanese Protestant Christian, says: "between ancient Phoenicia and the Lebanon of medieval and modern times, there is no demonstrable historical connection".[15] Phoenicianism embraces Phoenicia as an alternative cultural foundation by overlooking 850 years of Arabisation.

The earliest sense of a modern Lebanese identity is to be found in the writings of historians in the early nineteenth century, when, under the emirate of the Shihabs, a Lebanese identity emerged, "separate and distinct from the rest of Syria, bringing the Maronites and Druzes, along with its other Christian and Muslim sects, under one government."[16] The first coherent history of Mount Lebanon was written by Tannus al-Shidyaq (died 1861) who depicted the country as a feudal association of Maronites, Druzes, Melkites, Sunnis and Shi'ites under the leadership of the Shihab emirs. "Most Christian Lebanese, anxious to dissociate themselves from Arabism and its Islamic connections, were pleased to be told that their country was the legitimate heir to the Phoenician tradition," Kamal Salibi observes, instancing Christian writers like Charles Corm (died 1963), writing in French, and Said Aql, who urged the abandonment of literary Arabic, together with its script, and attempted to write in the Lebanese vernacular, using the Roman alphabet.

Phoenician origins have additional appeal for the Christian middle class, as it presents the Phoenicians as traders, and the Lebanese emigrant as a modern-day Phoenician adventurer, whereas for the Sunni it merely veiled French imperialist ambitions, intent on subverting pan-Arabism.[17]

Critics believe that Phoenicianism is an origin myth that disregards the Arab cultural and linguistic influence on the Lebanese. They ascribe Phoenicianism to sectarian influences on Lebanese culture and the attempt by Lebanese Maronites to distance themselves from Arab culture and traditions.

The counter position is summed by As'ad AbuKhalil, Historical Dictionary of Lebanon (London: Scarecrow Press), 1998:

Ethnically speaking, the Lebanese are indistinguishable from the peoples of the eastern Mediterranean. They are undoubtedly a mixed population, reflecting centuries of population movement and foreign occupation... While Arabness is not an ethnicity but a cultural identity, some ardent Arab nationalists, in Lebanon and elsewhere, talk about Arabness in racial and ethnic terms to elevate the descendants of Muhammad. Paradoxically, Lebanese nationalists also speak about the Lebanese people in racial terms, claiming that the Lebanese are "pure" descendants of the Phoenician peoples, whom they view as separate from the ancient residents of the region, including — ironically — the Canaanites.

Proponents of Phoenician continuity among Maronite Christians point out that a Phoenician identity, including the worship of pre-Christian Phoenician gods such as Baal, El, Astarte and Adon was still in evidence until the mid 4th century AD, and was only gradually replaced by Christianity during the 4th and 5th centuries AD. Furthermore, that all this happened centuries before the Arab-Islamic Conquest.[18]

See also

Notes

- ↑ El-Husseini, Rola (2012). Pax Syriana: Elite Politics in Postwar Lebanon. Syracuse University Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-8156-3304-4.

Phoenicianism. The "Phoenicianist" discourse of Lebanese identity was adopted by Christian (primarily Maronite) intellectuals at the time of the creation of Greater Lebanon. The Maronites' stated goal of establishing a Christian refuge in the Middle East was instrumental in convincing the French authorities to designate Lebanon as a separate nation-state. The origin myth adopted by the Christian advocates involved a purportedly independent cultural legacy that was said to have existed in Lebanon since ancient times.

- ↑ Kraidy, Marwan (2005), Hybridity, Or the Cultural Logic of Globalization, Temple University Press, p. 119, ISBN 978-1-59213-145-7,

Some scholars suggest that the Maronites are the descendants of "the worshippers of Adonis and Astarte," “Assyrians who emerged from Mesopotamia" (Melia, 1986, p. 154). Another theory claims that the Maronites are the descendants of an Arab Bedouin population, the Nabateans, who settled in the Levant during the pre-Christian era (Valognes, 1994, p. 369). A third theory, based on the work of the historian Theophanes, presents the Maronites as the heirs of an Anatolian or Iranian population, the Mardaites, who were allegedly militarily used by the Byzantines against the Arabs because of the Mardaites' outstanding fighting skills (Melia, 1986, p. 158; Nisan, 1992, p. 171; Valognes, 1994, p. 369). According to the fourth and last theory, the Maronites descend from the Phoenicians, a claim held by some Maronite (and other Christian Lebanese) intellectuals as a key building block of their identity, which some scholars dispute (Salibi, 1988; Tabar, 1994; Valognes, 1994), and others support (Gemayel, 1984a, b; Melia, 1986; Nisan, 1992). Chabry and Chabry (1987), among others (Melia, 1986; Nisan, 1992; Tabar, 1994; Valognes, 1994), argue that Maronite claims of a Phoenician heritage are not unfounded (p. 55), because the ethnic makeup of the Maronites is a mixture of Mardaite, Greco-Phoenician, Aramean, Franc, Armenian, and Arab dements (p. 305). In spite of this mixed origin, the Maronites are said to have maintained a presumably unchanging identity - fiercely autonomous from both Muslims and other Christians - remained "untamed in their ways of living and thinking" (Melia, 1986, p. 159; see also Nisan, 1992, p. 171).

- ↑ Kraidy, Marwan (2005), Hybridity, Or the Cultural Logic of Globalization, Temple University Press, p. 119, ISBN 978-1-59213-145-7,

The Phoenician-roots theory parallels the belief among Copts in Egypt and Nestorians in Iraq, both Christian communities, that they have respectively Pharaonic and ancient Assyrian roots.

- ↑ "Si Beyrouth Parlait", Lina Murr Nehme

- ↑ "La Palestine, l'Argent et le Petrole", Lina Murr Nehme

- ↑ In Lebanon DNA may yet heal rifts

- ↑ Salameh, Franck (Fall 2011). "Does Anyone Speak Arabic". Middle East Quarterly. 18 (4): 50. Retrieved 2014-10-26.

- ↑ Walter J. Ong, Interfaces of the Word: Studies in the Evolution of Consciousness and Culture, pg. 32. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012. ISBN 9780801466304

- ↑ Nizar Y. Habash,Introduction to Arabic Natural Language Processing, pgs. 1-2. San Rafael: Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2010. ISBN 9781598297959

- ↑ Richard, Suzanne (2003). Near Eastern Archaeology: A Reader (Illustrated ed.). EISENBRAUNS. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-57506-083-5.

- ↑ "Aramaic Maronite Center". Aramaic-center.com. Retrieved 2012-11-26.

- ↑ Perlin, Ross (August 14, 2014). "Is the Islamic State Exterminating the Language of Jesus?". Foreign Policy. Graham Holdings Company.

- ↑ Rola L. Husseini (2012). Pax Syriana: Elite Politics in Postwar Lebanon. Syracuse University Press. p. 42.

- ↑ Dutch: Leonard C. Biegel, Minderheden in Het Midden-Oosten: Hun Betekenis Als Politieke Factor in De Arabische Wereld, Van Loghum Slaterus, Deventer, 1972, ISBN 978-90-6001-219-2

- ↑ Salibi, Salibi, A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered, 1988:177; Salibi is equally critical of an "Arabian" cultural origin.

- ↑ Kamal S. Salibi, "The Lebanese Identity" Journal of Contemporary History 6.1, Nationalism and Separatism (1971:76-86).

- ↑ Salibi 1971:84.

- ↑ http://www.maronitehistory.org/Maronite_Phoenician_Heritage

Further reading

- Kaufman, Asher, "Phoenicianism: The Formation of an Identity in Lebanon in 1920" Middle Eastern Studies, (January, 2001)

- Kaufman, Asher (2004). Reviving Phoenicia: In Search of Identity in Lebanon. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-982-3.

- Salibi, Kamal Suleiman (2003). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-912-2.

- Plonka Arkadiusz, L’idée de langue libanaise d’après Sa‘īd ‘Aql, Paris, Geuthner, 2004 (French) ISBN 2-7053-3739-3

- Plonka Arkadiusz, "Le nationalisme linguistique au Liban autour de Sa‘īd ‘Aql et l’idée de langue libanaise dans la revue «Lebnaan» en nouvel alphabet", Arabica, 53 (4), 2006, pp. 423–471. (French)

- Salameh, Franck, Language Memory and Identity in the MIddle East; The Case for Lebanon, Lanham, MD, Lexington Books, 2010, ISBN 0739137395

External links

- National Geographic: "Who Were the Phoenicians?"

- National Geographic: "In the Wake of the Phoenicians:DNA study reveals a Phoenician-Maltese link"

- The Irish Lebanese Cultural Foundation: "A parallel in History between Lebanon and Ireland"