Acoustic metamaterial

| Continuum mechanics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

Laws

|

||||

An acoustic metamaterial is a material designed to control, direct, and manipulate sound waves as these might occur in gases, liquids, and solids. The hereditary line into acoustic metamaterials follows from theory and research in negative index material. Furthermore, with acoustic metamaterials controlling sonic waves can now be extended to the negative refraction domain.[1]

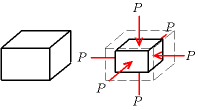

Control of the various forms of sound waves is mostly accomplished through the bulk modulus β, mass density ρ, and chirality. The density and bulk modulus are analogies of the electromagnetic parameters, permittivity and permeability in negative index materials. Related to this is the mechanics of wave propagation in a lattice structure. Also materials have mass, and instrinsic degrees of stiffness. Together these form a resonant system, and the mechanical (sonic) resonance may be excited by appropriate sonic frequencies (for example pulses at audio frequencies).[1]

History

Acoustic metamaterials have developed from the research and results behind metamaterials. The novel material was originally proposed by Victor Veselago in 1967, but not realized until some 33 years later. John Pendry produced the basic elements of metamaterials during the last part of the 1990s. His materials were combined and then negative index materials were realized first in the year 2000 and 2001 which produced a negative refraction thereby broadening possible optical and material responses. Hence, research in acoustic metamaterials has the same goal of broader material response with sound waves.[2][3][4][5][6][6][7][8][9]

Research employing acoustic metamaterials began in the year 2000 with the fabrication and demonstration of sonic crystals in a liquid.[10] This was followed by transposing the behavior of the split-ring resonator to research in acoustic metamaterials.[11] After this double negative parameters (negative bulk modulus βeff and negative density ρeff) were produced by this type of medium.[12] Then a group of researchers presented the design and tested results of an ultrasonic metamaterial lens for focusing 60 kHz.[13]

The earlier studies of acoustics in technology, which is called acoustical engineering, are typically concerned with how to reduce unwanted sounds, noise control, how to make useful sounds for the medical diagnosis, sonar, and sound reproduction and how to measure some other physical properties using sound.

Using acoustic metamaterials the directions of sound through the medium can be controlled by manipulating the refractive index. Therefore, the traditional acoustic technologies are extended and may eventually cloak certain objects from acoustic detection.

Basic principles

Since the acoustic metamaterials are one of the branch of the metamaterials, the basic principle of the acoustic metamaterials is similar to the principle of metamaterials. These metamaterials usually gain their properties from structure rather than composition, using the inclusion of small inhomogeneities to enact effective macroscopic behavior.[6][14] Similar to metamaterials research, investigating materials with Negative index metamaterials, the negative index acoustic metamaterials became the primary research. Negative refractive index of acoustic materials can be achieved by changing the bulk modulus and mass density.

Bulk modulus and mass density

Below, the bulk modulus β of a substance reflects the substance's resistance to uniform compression. It is defined in relation to the pressure increase needed to cause a given relative decrease in volume.

The mass density (or just "density") of a material is defined as mass per unit volume and is expressed in grams per cubic centimeter (g/cm3).[15] In all three classic states of matter — gas, liquid, or solid — the density varies with a change in temperature or pressure, and gases are the most susceptible to those changes. The spectrum of densities is wide ranging: from 1015 g/cm3 for neutron stars, 1.00 g/cm3 for water to 1.2×10−3 g/cm3 for air.[15] Also relevant here are area density which is mass over a (two-dimensional) area, linear density - mass over a one-dimensional line, and relative density, which is a density divided by the density of a reference material, such as water.

For acoustic materials and acoustic metamaterials, both bulk modulus and density are component parameters, which define their refractive index.

Analogues

Scientific research revealed that acoustic metamaterials have analogues to electromagnetic metamaterials when exhibiting the following characteristics:

In certain frequency bands, the effective mass density and bulk modulus may become negative. This results in a negative refractive index. Flat slab focusing, which can result in super resolution, is similar to electromagnetic metamaterials. The double negative parameters are a result of low-frequency resonances.[1] In combination with a well-defined polarization during wave propagation; k = |n|ω, is an equation for refractive index as sound waves interact with acoustic metamaterials (below):[16]

The inherent parameters of the medium are the mass density ρ, bulk modulus β, and chirality k. Chirality, or handedness, determines the polarity of wave propagation (wave vector). Hence within the last equation, Veselago-type solutions (n2 = u*ε) are possible for wave propagation as the negative or positive state of ρ and β determine the forward or backward wave propagation.[16]

In negative refractive, electromagnetic metamaterials, negative permittivity can be found in natural materials. However, negative permeability has to be intentionally created in the artificial transmission medium. Obtaining a negative refractive index with acoustic materials is different.[16] Neither negative ρ nor negative β are found in naturally occurring materials;[16] they are derived from the resonant frequencies of an artificially fabricated transmission medium (metamaterial), and such negative values are an anomalous response. Negative ρ or β means that at certain frequencies the medium expands when experiencing compression (negative modulus), and accelerates to the left when being pushed to the right (negative density).[16]

Electromagnetic field vs acoustic field

The electromagnetic spectrum extends from below frequencies used for modern radio to gamma radiation at the short-wavelength end, covering wavelengths from thousands of kilometers down to a fraction of the size of an atom. That would be wavelengths from 103 to 10−15 kilometers. The long wavelength limit is the size of the universe itself, while it is thought that the short wavelength limit is in the vicinity of the Planck length, although in principle the spectrum is infinite and continuous.

Infrasonic frequencies range from 20 Hz down to 0.001 Hz. Audible frequencies are 20 Hz to 20 kHz. Ultrasonic range is above 20 kHz. Sound requires a medium. Electromagnetics radiation (EM waves) can travel in a vacuum.

Mechanics of lattice waves

An imaginary demonstration: A hypothetical rigid lattice structure (solid) is composed of 1023 atoms. However, in a real solid these particles could just as easily be ions. In a rigid lattice structure, atoms exert pressure, or a force, on each other in order to maintain equilibrium. Atomic forces maintain rigid lattice structure. Most of them, such as the covalent or ionic bonds, are of electric nature. The magnetic force, and the force of gravity are negligible.[17] Because of bonding between atoms, the displacement of one or more atoms from their equilibrium positions will give rise to a set of vibration waves propagating through the lattice. One such wave is shown in the figure to the right. The amplitude of the wave is given by the displacements of the atoms from their equilibrium positions. The wavelength λ is marked.[18]

There is a minimum possible wavelength, given by the equilibrium separation a between atoms. Any wavelength shorter than this can be mapped onto a wavelength longer than a, due to effects similar to that in aliasing.[18]

Analysis and experiments

The current research on acoustic metamaterials is based not only on prior experience with electromagnetic metamaterials. The key physics in acoustics are sound, ultrasound and infrasound, which are mechanical waves in gases, liquids, and solids. One objective of the inquiry into the properties of acoustic metamaterials is applications in seismic wave reflection and in vibration control technologies related to earthquakes.[1][10][19]

Sonic crystals

In the year 2000 the research of Liu et al. paved the way to acoustic metamaterials through sonic crystals. The latter exhibit spectral gaps two orders of magnitude smaller than the wavelength of sound. The spectral gaps prevent the transmission of waves at prescribed frequencies. The frequency can be tuned to desired parameters by varying the size and geometry of the metamaterial.[10]

The fabricated material consisted of a high-density solid lead ball as the core, one centimeter in size, which was coated with a 2.5-mm layer of rubber silicone. These were arranged in a crystal lattice structure of an 8 × 8 × 8 cube. The balls were cemented into the cubic structure with an epoxy. Transmission was measured as a function of frequency from 250 to 1600 Hz for effectively a four-layer sonic crystal. A two-centimeter slab absorbed sound that normally would require a much thicker material, at 400 Hz. A drop in amplitude was observed at 400 and 1100 Hz.[10][20]

The amplitudes of the sound waves entering the surface were compared with the sound waves at the center of the metamaterial structure. The oscillations of the coated spheres absorbed sonic energy, which created the frequency gap; the sound energy is absorbed exponentially as the thickness of the material is increased. The key result here is a negative elastic constant created from resonant frequencies of the material. Its projected applications, with a future expanded frequency range in elastic wave systems, are seismic wave reflection and ultrasonics.[10][20]

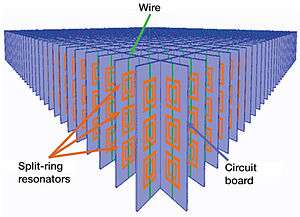

Split-ring resonators for acoustic metamaterials

In 2004 split-ring resonators (SRR) became the object of acoustic metamaterial research.[19] Prior research with SRRs fabricated as negative index electromagnetic metamaterials was referenced as the progenitor of further research in acoustic metamaterials.[19] An analysis of the frequency band gap characteristics, derived from the inherent limiting properties of artificially created SRRs, paralleled an analysis of sonic crystals. The band gap properties of SRRs were related to sonic crystal band gap properties.[19] Inherent in this inquiry is a description of mechanical properties and problems of continuum mechanics for sonic crystals, as a macroscopically homogeneous substance.[19]

The correlation in bandgap capabilities includes locally resonant elements and elastic moduli which operate in a certain frequency range. Elements which interact and resonate in their respective localized area are embedded throughout the material. In acoustic metamaterials, locally resonant elements would be the interaction of a single 1-cm rubber sphere with the surrounding liquid. The values of the stop band and band gap frequencies can be controlled by choosing the size, types of materials, and the integration of microscopic structures which control the modulation of the frequencies. These materials are then able to shield acoustic signals and attenuate the effects of anti-plane shear waves. By extrapolating these properties to larger scales it could be possible to create seismic wave filters (see Seismic metamaterials).[19]

According to research prior to this analysis, arrayed metamaterials can create filters or polarizers of either electromagnetic or elastic waves.[19] Here a method is shown which can be applied to two-dimensional stop band and bandgap control with either photonic or sonic structures.[19] Similar to photonic and electromagnetic metamaterial fabrication, a sonic metamaterial is embedded with localized sources of mass density ρ and the (elastic) bulk modulus β parameters, which are analogous to permittivity and permeability, respectively. The sonic (or phononic) metamaterials are sonic crystals, as in the previous section. These crystals have a solid lead core and a softer, more elastic silicone coating.[10] The sonic crystals had built-in localized resonances due to the coated spheres which resulted in almost flat dispersion curves. Low-frequency bandgaps and localized wave interactions of the coated spheres were analyzed and presented in.[19]

This method can be used to tune bandgaps inherent in the material and, also, create new low-frequency bandgaps. It is also applicable for designing low-frequency phononic crystal waveguides (radio frequency). Doubly periodic square array of SRRs are used to illustrate the methodology.[19]

Phononic crystal

Phononic crystals are synthetic materials that are formed by periodic variation of the acoustic properties of the material (i.e., elasticity and mass). One of the main properties of the phononic crystals is the possibility of having a phononic bandgap. A phononic crystal with phononic bandgap prevents phonons of selected ranges of frequencies from being transmitted through the material.[22][23]

To obtain the frequency band structure of a phononic crystal, Bloch theory is applied on a single unit cell in the reciprocal lattice space (Brillouin zone). Several numerical methods are available for this problem, e.g., the planewave expansion method, the finite element method, and the finite difference method. A brief survey of numerical methods for calculating the frequency band structure is provided by Hussein (2009)[24]

In order to speed up the calculation of the frequency band structure, the Reduced Bloch Mode Expansion (RBME) method can be used.[24] The RBME applies "on top" of any of the primary expansion numerical methods mentioned above. For large unit cell models, the RBME method can reduce the time for computing the band structure by up to two orders of magnitude.

The basis of phononic crystals dates back to Isaac Newton who imagined that sound waves propagated through air in the same way that an elastic wave would propagate along a lattice of point masses connected by springs with an elastic force constant E. This force constant is identical to the modulus of the material. Of course with phononic crystals of materials with differing modulus the calculations are a little more complicated than this simple model.[22][23]

Based on Newton’s observation we can conclude that a key factor for acoustic band-gap engineering is impedance mismatch between periodic elements comprising the crystal and the surrounding medium. When an advancing wave-front meets a material with very high impedance it will tend to increase its phase velocity through that medium. Likewise, when the advancing wave-front meets a low impedance medium it will slow down. We can exploit this concept with periodic (and handcrafted) arrangements of impedance mismatched elements to affect acoustic waves in the crystal – essentially band-gap engineering.[22][23]

The position of the band-gap in frequency space for a phononic crystal is controlled by the size and arrangement of the elements comprising the crystal. The width of the band gap is generally related to the difference in the speed of sound (due to impedance differences) through the materials that comprise the composite.[22][23]

Double-negative acoustic metamaterial

The electromagnetic (isotropic) metamaterials have built-in resonance structures that exhibit effective negative permittivity and negative permeability for some frequency ranges. In contrast, it is difficult to build composite acoustic materials with built-in resonances such that the two effective response functions are negative within the capability or range of the transmission medium.[12]

The mass density ρ and bulk modulus β are position dependent. Using the formulation of a plane wave the wave vector is:[12]

The angular frequency is represented by ω and c is the propagation speed of acoustic signal through the homogeneous medium. With constant density and bulk modulus as constituents of the medium, the refractive index is expressed as n2 = ρ / β. In order to develop a propagating (plane) wave through the material, it is necessary for both ρ and β to be either positive or negative.[12]

When the negative parameters are achieved, the mathematical result of the Poynting vector . is the opposite direction of the wave vector . This requires negativity in bulk modulus and density. Physically, it means that the medium displays an anomalous response at some frequencies such that it expands upon compression (negative bulk modulus) and moves to the left when being pushed to the right (negative density) at the same time.[12]

Natural materials do not have a negative density or a negative bulk modulus, but, negative values are mathematically possible, and can be demonstrated when dispersing soft rubber in a liquid.[12][25][26]

Even for composite materials, the effective bulk modulus and density should be normally bounded by the values of the constituents, i.e., the derivation of lower and upper bounds for the elastic moduli of the medium. Intrinsic is the expectation for positive bulk modulus and positive density. For example, dispersing spherical solid particles in a fluid results in the ratio governed by the specific gravity when interacting with the long acoustic wavelength (sound). Mathematically, it can be easily proven that βeff and ρeff are definitely positive for natural materials.[12][25] The exception occurs at low resonant frequencies.[12]

As an example, acoustic double negativity is theoretically demonstrated with a composite of soft, silicone rubber spheres suspended in water.[12] In soft rubber, sound travels much slower than through the water. The high velocity contrast of sound speeds between the rubber spheres and the water allows for the transmission of very low monopolar and dipolar frequencies. This is an analogue to analytical solution for the scattering of electromagnetic radiation, or electromagnetic plane wave scattering, by spherical particles - dielectric spheres.[12]

Hence, there is a narrow range of normalized frequency 0.035 < ωa/(2πc) < 0.04 where the bulk modulus and negative density are both negative. Here a is the lattice constant if the spheres are arranged in a face-centered cubic (fcc) lattice; ω is frequency and c is speed of the acoustic signal. The effective bulk modulus and density near the static limit are positive as predicted. The monopolar resonance creates a negative bulk modulus above the normalized frequency at about 0.035 while the dipolar resonance creates a negative density above the normalized frequency at about 0.04.[12]

This behavior is analogous to low-frequency resonances produced in SRRs (electromagnetic metamaterial). The wires and split rings create intrinsic electric dipolar and magnetic dipolar response. With this artificially constructed acoustic metamaterial of rubber spheres and water, only one structure (instead of two) creates the low-frequency resonances to achieve double negativity.[12] With monopolar resonance, the spheres expand, which produces a phase shift between the waves passing through rubber and water. This creates the negative response. The dipolar resonance creates a negative response such that the frequency of the center of mass of the spheres is out of phase with the wave vector of the sound wave (acoustic signal). If these negative responses are large enough to compensate the background fluid, one can have both negative effective bulk modulus and negative effective density.[12]

Both the mass density and the reciprocal of the bulk modulus are decreasing in magnitude fast enough so that the group velocity becomes negative (double negativity). This gives rise to the desired results of negative refraction. The double negativity is a consequence of resonance and the resulting negative refraction properties.

Metamaterial with simultaneously negative bulk modulus and mass density

In August 2007 a metamaterial was reported which simultaneously possesses a negative bulk modulus and mass density. This metamaterial is a zinc blende structure consisting of one fcc array of bubble-contained-water spheres (BWSs) and another relatively shifted fcc array of rubber-coated-gold spheres (RGSs) in special epoxy.[27]

Negative bulk modulus is achieved through monopolar resonances of the BWS series. Negative mass density is achieved with dipolar resonances of the gold sphere series. Rather than rubber spheres in liquid, this is a solid based material. This is also as yet a realization of simultaneously negative bulk modulus and mass density in a solid based material, which is an important distinction.[27]

Double C resonators

Double C resonator (DCR) is a ring cut in halves. In 2007, proposals have been made for arrays of DCRs and similar negative acoustic metamaterial.[1] Although linear elasticity is mentioned, the problem is defined around shear waves directed at angles to the plane of the cylinders. The DCR was constructed similar to the SRRs in a multiple cell configuration. The DCR has been improved with stiffer material sheets.[1] Each cell consists of a large rigid disk and two thin ligaments.[1] The DCR cell is a tiny oscillator connected by springs. One spring of the oscillator connects to the mass and is anchored by the other spring. The LC resonator has specified capacitance and inductance.[1] The limitations are expressed with appropriate mathematical equations. In addition to the intended limitations is that the speed of sound in the matrix is expressed as c = √ρ/µ with a matrix of density ρ and shear modulus μ. The resonant frequency is then expressed as √1/(LC).[1]

A phononic bandgap occurs in association with the resonance of the split cylinder ring. There is a phononic band gap within a range of normalized frequencies. This is when the inclusion moves as a rigid body.

The DCR design produced a suitable band with negative slope in a range of frequencies. This band was obtained by hybridizing the modes of a DCR with the modes of thin stiff bars. Calculations have shown that at these frequencies:

- a beam of sound negatively refracts across a slab of such a medium,

- the phase vector in the medium possesses real and imaginary parts with opposite signs,

- the medium is well impedance-matched with the surrounding medium,

- a flat slab of the metamaterial can image a source across the slab like a Veselago lens,

- the image formed by the flat slab has considerable sub-wavelength image resolution, and

- a double corner of the metamaterial can act as an open resonator for sound.

Acoustic metamaterial superlens

In May 2009 Shu Zhang et al. presented the design and test results of an ultrasonic metamaterial lens for focusing 60 kHz (~2 cm wavelength) sound waves under water.[13] The lens is made of sub-wavelength elements and is therefore potentially more compact than phononic lenses that operate in the same frequency range.[13]

High-resolution acoustic imaging techniques are the essential tools for nondestructive testing and medical screening. However, the spatial resolution of the conventional acoustic imaging methods is restricted by the incident wavelength of ultrasound. This is due to the quickly fading evanescent fields which carry the sub-wavelength features of objects.[28]

The lens consists of a network of fluid-filled cavities called Helmholtz resonators that oscillate at certain sonic frequencies. Similar to a network of inductors and capacitors in electromagnetic metamaterial, the arrangement of Helmholtz cavities designed by Zhang et al. have a negative dynamic modulus for ultrasound waves. Zhang et al. did focus a point source of 60.5 kHz sound to a spot size that is roughly the width of half a wavelength and their design may allow to push the spatial resolution even further.[13] This result is in excellent agreement with the numerical simulation by transmission line model, which derived the effective mass density and compressibility. This metamaterial lens also displays variable focal length at different frequencies.[28][29]

Acoustic diode

An acoustic diode was introduced in August 2009. An electrical diode allows current to flow in only one direction in a wire; it is an essential electronic device which had no analogues for sound waves. However, the reported design partially fills this role by converting sound to a new frequency and blocking any backwards flow of the original frequency. In practice, it could give designers new flexibility in making ultrasonic sources like those used in medical imaging. The proposed structure combines two components: The first is a sheet of nonlinear acoustic material—one whose sound speed varies with air pressure. An example of such a material is a collection of grains or beads, which becomes stiffer as it is squeezed. The second component is a filter that allows the doubled frequency to pass through but reflects the original.[30][31]

Acoustic cloaking

An acoustic cloak is a hypothetical device that would make objects impervious towards sound waves. This could be used to build sound proof homes, advanced concert halls, or stealth warships. The mathematics and physics behind acoustic cloaking has been known for several years. The idea of acoustic cloaking is to deviate the sounds waves around the object that has to be cloaked. But realizing it in materials has been difficult, since mechanical metamaterials are needed. The key to this problem are acoustic metamaterials also known as "Sonic Crystals." Making a metamaterial for sound means identifying the acoustic analogues to permittivity and permeability in light waves. It turns out that these are the material's mass density and its elastic constant. Researchers from Wuhan University, China in a paper[32] in 2007 reported such a metamaterial which simultaneously possessed a negative bulk modulus and mass density.

Potential applications

If such a material could be commercialized, researchers believe it could have many applications. Walls of the material could be built to soundproof houses or it could be used in concert halls to enhance acoustics or direct noise away from certain areas. The military may also be interested to conceal submarines from detection by sonar or to create a new class of stealth ships.

Metamaterial acoustic cloak

A laboratory metamaterial device that is applicable to ultra-sound waves has been demonstrated in January 2011. It can be applied to sound wavelengths from 40 to 80 kHz.

The metamaterial acoustic cloak is designed to hide objects submerged in water. The metamaterial cloaking mechanism bends and twists sound waves by intentional design.

The cloaking mechanism consists of 16 concentric rings in a cylindrical configuration, and each ring with acoustic circuits. It is intentionally designed to guide sound waves, in two dimensions. The first microwave metamaterial cloak guided electromagnetic waves in two dimensions.

Each ring has a different index of refraction. This causes sound waves to vary their speed from ring to ring. "The sound waves propagate around the outer ring, guided by the channels in the circuits, which bend the waves to wrap them around the outer layers of the cloak". This device has been described as an array of cavities which actually slow the speed of the propagating sound waves. An experimental cylinder was submerged in tank, and then it disappeared from sonar. Other objects of various shape and density were also hidden from the sonar. The acoustic cloak demonstrated effectiveness for the sound wavelengths of 40 kHz to 80 kHz.[29][33][34][35][36]

Phononic metamaterials for thermal management

As phonons are responsible for thermal conduction in solids, acoustic metamaterials may be designed to control heat transfer.[37][38]

See also

Metamaterials scientists |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Guenneau, Sébastien; Alexander Movchan; Gunnar Pétursson; S. Anantha Ramakrishna (2007). "Acoustic metamaterials for sound focusing and confinement". New Journal of Physics. 9 (399): 1367–2630. Bibcode:2007NJPh....9..399G. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/9/11/399.

- ↑ Nahin, P.J., Spectrum, IEEE, Volume 29, Issue 3, March 1992 Page(s):45–

- ↑ "James Clerk Maxwell". IEEE Global History Network. 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-21.

- ↑ D.T., Emerson (December 1997). "The work of Jagadis Chandra Bose: 100 years of millimeter-wave research". Microwave Theory and Techniques, IEEE Transactions (A facility of the NSF provides added material to the original paper - The work of Jagadish Chandra Bose: 100 years of milmeter wave research.). 45 (12): 2267. Bibcode:1997ITMTT..45.2267E. doi:10.1109/22.643830.

- ↑ Bose, Jagadis Chunder (1898-01-01). "On the Rotation of Plane of Polarisation of Electric Waves by a Twisted Structure". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 63 (1): 146–152. doi:10.1098/rspl.1898.0019.

- 1 2 3 Nader, Engheta; Richard W. Ziolkowski (June 2006). Metamaterials: physics and engineering explorations. Wiley & Sons. pp. xv. ISBN 978-0-471-76102-0.

- ↑ Engheta, Nader (2004-04-29). "Metamaterials" (Nader Engheta co-authored Metamaterials: physics and engineering explorations.). U Penn Dept. of Elec. and Sys. Engineering. Lecture. and Workshop: 99.

- ↑ Shelby, R. A.; Smith, D. R.; Schultz, S. (2001). "Experimental verification of a negative index of refraction". Science. 292 (5514): 77–79. Bibcode:2001Sci...292...77S. doi:10.1126/science.1058847. PMID 11292865.

- ↑ Negative refraction (electromagnetic) first demonstrated by D. Smith, S. Shultz, and R. Shelby (2000–2001)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Zhengyou Liu, Liu; Xixiang Zhang; Yiwei Mao; Y. Y. Zhu; Zhiyu Yang; C. T. Chan; Ping Sheng (2000). "Locally Resonant Sonic Materials". Science. 289 (5485): 1734–1736. Bibcode:2000Sci...289.1734L. doi:10.1126/science.289.5485.1734. PMID 10976063.

- 1 2 Smith, D. R.; Padilla, WJ; Vier, DC; Nemat-Nasser, SC; Schultz, S (2000). "Composite Medium with Simultaneously Negative Permeability and Permittivity" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 84 (18): 4184–7. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..84.4184S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.4184. PMID 10990641. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-03-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Li, Jensen; C. T. Chan (2004). "Double-negative acoustic metamaterial". Phys. Rev. E. 70 (5): 055602. Bibcode:2004PhRvE..70e5602L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.70.055602.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomas, Jessica; Yin, Leilei; Fang, Nicholas (2009-05-15). "Metamaterial brings sound into focus" (synopsis for Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 194301). Physics. American Physical Society. 102 (19): 194301. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102s4301Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.194301. PMID 19518957. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- ↑ Smith, David R. (2006-06-10). "What are Electromagnetic Metamaterials?". Novel Electromagnetic Materials. The research group of D.R. Smith. Archived from the original on July 20, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- 1 2 "Density". Encyclopedia Americana. Grolier. Online. Scholastic Inc. 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Krowne, Clifford M.; Yong Zhang (2007). Physics of Negative Refraction and Negative Index Materials: Optical and Electronic Aspects and Diversified Approaches. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 183 (Chapter 8). ISBN 978-3-540-72131-4.

- ↑ Lavis, David Anthony; George Macdonald Bell (1999). Statistical Mechanics Of Lattice Systems. Volume 2. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-3-540-64436-1.

- 1 2 Brulin, Olof; Richard Kin Tchang Hsieh (1982). Mechanics of micropolar media. World Scientific Publishing Company. pp. 3–11. ISBN 9971-950-02-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Movchan, A. B.; S. Guenneau (2004). "Split-ring resonators and localized modes" (PDF). Phys. Rev. B. 70 (12): 125116. Bibcode:2004PhRvB..70l5116M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.70.125116. Retrieved 2009-08-27.

- 1 2 Sonic crystals make the sound barrier. Institute of Physics. 2000-09-07. Retrieved 2009-08-25.

- ↑ Shelby, R. A.; Smith, D. R.; Nemat-Nasser, S. C.; Schultz, S. (2001). "Microwave transmission through a two-dimensional, isotropic, left-handed metamaterial". Applied Physics Letters. 78 (4): 489. Bibcode:2001ApPhL..78..489S. doi:10.1063/1.1343489.

- 1 2 3 4 Gorishnyy, Taras; Martin Maldovan; Chaitanya Ullal; Edwin Thomas (2005-12-01). "Sound ideas". Physicsworld.com. Institute of Physics. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- 1 2 3 4 G.P Srivastava (1990). The Physics of Phonons. CRC Press. ISBN 0-85274-153-7.

- 1 2 M.I. Hussein (2009). "Reduced Bloch mode expansion for periodic media band structure calculations". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 465 (2109): 2825–2848. arXiv:0807.2612

. Bibcode:2009RSPSA.465.2825H. doi:10.1098/rspa.2008.0471.

. Bibcode:2009RSPSA.465.2825H. doi:10.1098/rspa.2008.0471. - 1 2 Trostmann, Erik (2000-11-17). Tap water as a hydraulic pressure medium. CRC Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8247-0505-3.

- ↑ Petrila, Titus; Damian Trif (December 2004). Basics of fluid mechanics and introduction to computational fluid dynamics. Springer-Verlag New York, LLC. ISBN 978-0-387-23837-1.

- 1 2 Ding, Yiqun; et al. (2007). "Metamaterial with Simultaneously Negative Bulk Modulus and Mass Density". Phys. Rev. Lett. 99 (9): 093904. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..99i3904D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.093904. PMID 17931008.

- 1 2 Zhang, Shu; Leilei Yin; Nicholas Fang (2009). "Focusing Ultrasound with Acoustic Metamaterial Network". Phys. Rev. Lett. American Physical Society. 102 (19): 194301. arXiv:0903.5101

. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102s4301Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.194301. PMID 19518957.

. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102s4301Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.194301. PMID 19518957. - 1 2 Adler, Robert; Acoustic metamaterials., Negative refraction. Earthquake protection. (2008). "Acoustic 'superlens' could mean finer ultrasound scans". New Scientist Tech. p. 1. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- ↑ Monroe, Don (2009-08-25). "One-way Mirror for Sound Waves" (synopsis for "Acoustic Diode: Rectification of Acoustic Energy Flux in One-Dimensional Systems" by Bin Liang, Bo Yuan, and Jian-chun Cheng). Physical Review Focus. American Physical Society. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- ↑ Li, Baowen; Wang, L; Casati, G (2004). "Thermal Diode: Rectification of Heat Flux". Physical Review Letters. 93 (18): 184301. arXiv:cond-mat/0407093

. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..93r4301L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.184301. PMID 15525165.

. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..93r4301L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.184301. PMID 15525165. - ↑ Ding, Yiqun; Liu, Zhengyou; Qiu, Chunyin; Shi, Jing (2007). "Metamaterial with Simultaneously Negative Bulk Modulus and Mass Density". Physical Review Letters. 99 (9): 093904. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..99i3904D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.093904. PMID 17931008.

- ↑ Zhang, Shu; Chunguang Xia; Nicholas Fang (2011). "Broadband Acoustic Cloak for Ultrasound Waves". Phys. Rev. Lett. American Physical Society. 106 (2): 024301. arXiv:1009.3310

. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106s4301Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.024301. PMID 21405230.

. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106s4301Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.024301. PMID 21405230. - ↑ Nelson, Bryn (January 19, 2011). "New metamaterial could render submarines invisible to sonar". Defense Update. Archived from the original (Online) on January 22, 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ↑ "Acoustic cloaking could hide objects from sonar". Information for Mechanical Science and Engineering. University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign). April 21, 2009. Archived from the original (Online) on August 27, 2009. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ "Newly Developed Cloak Hides Underwater Objects From Sonar". U.S. News - Science (Online). 2011 U.S.News & World Report. January 7, 2011. Archived from the original on February 17, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ↑ "Phononic Metamaterials for Thermal Management: An Atomistic Computational Study." Chinese Journal of Physics vol. 49 , no. 1 February 2011.

- ↑ Roman, Calvin T. "Investigation of Thermal Management and Metamaterials." Air Force Inst. of Tech Wright-Patterson AFB OH School of Engineering and Management, March 2010.

Further reading

- Leonhardt, Ulf; Smith, David R (2008). "Focus on Cloaking and Transformation Optics". New Journal of Physics. 10 (11): 115019. Bibcode:2008NJPh...10k5019L. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/10/11/115019.

- Fang, Nicholas; Xi, Dongjuan; Xu, Jianyi; Ambati, Muralidhar; Srituravanich, Werayut; Sun, Cheng; Zhang, Xiang (2006). "Ultrasonic metamaterials with negative modulus" (PDF). Nature Materials. 5 (6): 452–6. Bibcode:2006NatMa...5..452F. doi:10.1038/nmat1644. PMID 16648856. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 23, 2010.

- Zhang, Shu; Xia, Chunguang; Fang, Nicholas (2011). "Broadband Acoustic Cloak for Ultrasound Waves" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 106. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106b4301Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.024301.

- Pendry, J B; Li, Jensen (2008). "An acoustic metafluid: realizing a broadband acoustic cloak". New Journal of Physics. 10 (11): 115032. Bibcode:2008NJPh...10k5032P. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/10/11/115032.

- Richard V. Craster, et al.: Acoustic metamaterials: negative refraction, imaging, lensing and cloaking. Springer, Dordrecht 2013, ISBN 978-94-007-4812-5.

External links

- Ideas underpinning sound

- Acoustic Metamaterials and Devices: Negative, Positive, and Zero Refraction and Super-lensing in Phononic Crystals

- http://iopscience.iop.org/1367-2630/10/11/115032

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7450321.stm

- http://www.newscientist.com/blog/technology/2007/08/how-to-build-acoustic-invisibility.html