Photoplethysmogram

| Photoplethysmography | |

|---|---|

| Diagnostics | |

| MeSH | D017156 |

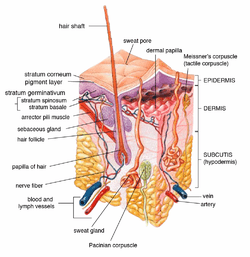

A photoplethysmogram (PPG) is an optically obtained plethysmogram, a volumetric measurement of an organ. A PPG is often obtained by using a pulse oximeter which illuminates the skin and measures changes in light absorption.[1] A conventional pulse oximeter monitors the perfusion of blood to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue of the skin.

With each cardiac cycle the heart pumps blood to the periphery. Even though this pressure pulse is somewhat damped by the time it reaches the skin, it is enough to distend the arteries and arterioles in the subcutaneous tissue. If the pulse oximeter is attached without compressing the skin, a pressure pulse can also be seen from the venous plexus, as a small secondary peak.

The change in volume caused by the pressure pulse is detected by illuminating the skin with the light from a light-emitting diode (LED) and then measuring the amount of light either transmitted or reflected to a photodiode. Each cardiac cycle appears as a peak, as seen in the figure. Because blood flow to the skin can be modulated by multiple other physiological systems, the PPG can also be used to monitor breathing, hypovolemia, and other circulatory conditions.[2] Additionally, the shape of the PPG waveform differs from subject to subject, and varies with the location and manner in which the pulse oximeter is attached.

Sites for measuring PPG

While pulse oximeters are a commonly used medical device the PPG derived from them is rarely displayed, and is nominally only processed to determine heart rate. PPGs can be obtained from transmissive absorption (as at the finger tip) or reflection (as on the forehead).

In outpatient settings, pulse oximeters are commonly worn on the finger. However, in cases of shock, hypothermia, etc. blood flow to the periphery can be reduced, resulting in a PPG without a discernible cardiac pulse. In this case, a PPG can be obtained from a pulse oximeter on the head, with the most common sites being the ear, nasal septum, and forehead.

PPGs can also be obtained from the following organs:

- the vagina (vaginal photoplethysmograph)

- the clitoris (clitoral photoplethysmograph)

- the esophagus

Motion artifacts have been shown to be a limiting factor preventing accurate readings during exercise and free living conditions.

Uses

Monitoring heart rate and cardiac cycle

Because the skin is so richly perfused, it is relatively easy to detect the pulsatile component of the cardiac cycle. The DC component of the signal is attributable to the bulk absorption of the skin tissue, while the AC component is directly attributable to variation in blood volume in the skin caused by the pressure pulse of the cardiac cycle.

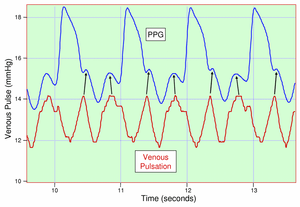

The height of AC component of the photoplethysmogram is proportional to the pulse pressure, the difference between the systolic and diastolic pressure in the arteries. As seen in the figure showing premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), the PPG pulse for the cardiac cycle with the PVC results in lower amplitude blood pressure and a PPG. Ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation can also be detected.

Monitoring respiration

Respiration affects the cardiac cycle by varying the intrapleural pressure, the pressure between the thoracic wall and the lungs. Since the heart resides in the thoracic cavity between the lungs, the partial pressure of inhaling and exhaling greatly influence the pressure on the vena cava and the filling of the right atrium. This effect is often referred to as normal sinus arrhythmia.

During inspiration, intrapleural pressure decreases by up to 4 mm Hg, which distends the right atrium, allowing for faster filling from the vena cava, increasing ventricular preload, but decreasing stroke volume. Conversely during expiration, the heart is compressed, decreasing cardiac efficiency and increasing stroke volume. When the frequency and depth of respiration increases, the venous return increases, leading to increased cardiac output.[3]

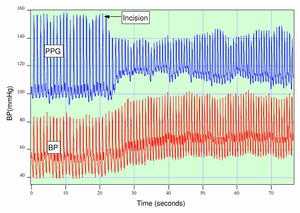

Monitoring depth of anesthesia

Anesthesiologists must often judge subjectively whether a patient is sufficiently anesthetized for surgery. As seen in the figure, if a patient is not sufficiently anesthetized, the sympathetic nervous system response to an incision can generate an immediate response in the amplitude of the PPG.

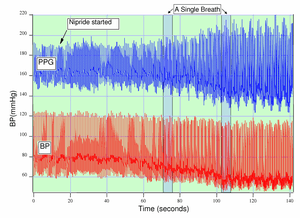

Monitoring hypo- and hypervolemia

Shamir, Eidelman, et al. studied the interaction between inspiration and removal of 10% of a patient’s blood volume for blood banking before surgery.[4] They found that blood loss could be detected both from the photoplethysmogram from a pulse oximeter and an arterial catheter. Patients showed a decrease in the cardiac pulse amplitude caused by reduced cardiac preload during exhalation when the heart is being compressed.

Photoplethysmograph

A photoplethysmograph is a device used to optically obtain a volumetric measurement of an organ.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ K. Shelley and S. Shelley, Pulse Oximeter Waveform: Photoelectric Plethysmography,in Clinical Monitoring, Carol Lake, R. Hines, and C. Blitt, Eds.: W.B. Saunders Company, 2001, pp. 420-428.

- ↑ A. T. Reisner, P. A. Shaltis, D. McCombie, and H. H. Asada, Utility of the Photoplethysmogram in Circulatory Monitoring, Anesthesiology, vol. 108, pp. 950-958, 2008.

- ↑ K. H. Shelley, D. H. Jablonka, A. A. Awad, R. G. Stout, H. Rezkanna, and D. G. Silverman, What Is the Best Site for Measuring the Effect of Ventilation on the Pulse Oximeter Waveform? Anesth Analg, vol. 103, pp. 372-377, 2006.

- ↑ M. Shamir, L. A. Eidelman, Y. Floman, L. Kaplan, and R. Pi-zov, Pulse Oximetry Plethysmographic Waveform During Changes in Blood Volume, Br. J. Anaesth., vol. 82, pp. 178-181, 1999.

- ↑ Allen J. Photoplethysmography and its application in clinical physiological measurement. Physiol Meas. 2007 Mar;28(3):R1-39. Epub 2007 Feb 20. Review. PubMed PMID 17322588.

External links

- A student project: building a device for collecting PPGs

- A free application for contactless photoplethysmogram measurements by means of Webcam