Piero the Unfortunate

| Piero de' Medici | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Piero de' Medici by Agnolo Bronzino. | |

| Lord of Florence | |

| Reign | 9 April 1492 – 9 November 1494 |

| Predecessor | Lorenzo de' Medici |

| Successor | Girolamo Savonarola |

| Spouse(s) | Alfonsina Orsini |

|

Issue | |

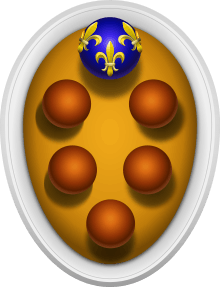

| Noble family | Medici |

| Father | Lorenzo de' Medici |

| Mother | Clarice Orsini |

| Born |

15 February 1472 Florence, Republic of Florence |

| Died |

28 December 1503 Garigliano River, Papal States |

Piero di Lorenzo de' Medici (15 February 1472 – 28 December 1503),[1] called Piero the Unfortunate, was the Gran maestro of Florence from 1492 until his exile in 1494.

Life and death

Piero di Lorenzo de' Medici was the eldest son of Lorenzo de' Medici (Lorenzo the Magnificent) and Clarice Orsini, and older brother of the future Pope Leo X.[1]

He was educated to succeed his father as head of the Medici family and de facto ruler of the Florentine state, under notable figures such as Angelo Poliziano. However, his feeble, arrogant and undisciplined character was to prove unsuited to such a role.

Piero took over as leader of Florence in 1492, upon Lorenzo's death. After a brief period of relative calm, the fragile pacific equilibrium between the Italian states, laboriously constructed by Piero's father, collapsed in 1494 with the decision of King Charles VIII of France to cross the Alps with an army in order to take the Kingdom of Naples, claiming hereditary rights. Charles had been lured to Italy by Ludovico Sforza, (Ludovico il Moro), ex-Regent of Milan, as a way to eject Ludovico's nephew Gian Galeazzo Sforza and replace him as Duke.

After settling matters in Milan, Charles moved towards Naples. He needed to pass through Tuscany, as well as leave troops there, securing his lines of communication with Milan. Piero attempted to stay neutral, but this was unacceptable to Charles, who intended to invade Tuscany. Piero attempted to mount a resistance, but received little support from Florentine elites, who had fallen under the influence of the fanatical Dominican priest Girolamo Savonarola; even his cousins defected to Charles's side.

Piero quickly gave up as Charles's army neared Florence and surrendered the chief fortresses of Tuscany to the invading army, giving Charles everything he demanded. His poor handling of the situation and failure to negotiate better terms led to an uproar in Florence, and the Medici family fled. The family palazzo was looted, and the substance as well as the form of the Republic of Florence was re-established, with the Medici formally exiled. A member of the Medici family was not to rule Florence again until 1512.

Piero and his family at first fled to Venice with the aid of Philippe de Commines. In 1503 as the French and Spanish continued their struggle in Italy over the Kingdom of Naples, Piero was drowned in the Garigliano River while attempting to flee the aftermath of the Battle of Garigliano, which the French (with whom he was allied) had lost.

Marriage and children

In 1486, Piero's uncle, Bernardo Rucellai negotiated for Piero to marry Alfonsina Orsini, and stood in for him in a marriage by proxy.[2] Piero and Alfonsina met in 1488. She was a daughter of Roberto Orsini, Count of Tagliacozzo and Caterina Sanseverino. They had two children:

- Lorenzo II, Duke of Urbino (1492-1519).[1]

- Clarice de' Medici (1493-1528). She married Filippo Strozzi the Younger.[1]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Piero the Unfortunate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- 1 2 3 4 Tomas 2003, p. 7.

- ↑ Gilbert 1949, p. 105.

Sources

- Gilbert, Felix (1949). "Bernardo Rucellai and the Orti Oricellari: A Study on the Origin of Modern Political Thought". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. Warburg Institute. 12: 101–131. doi:10.2307/750259. JSTOR 750259.

- Tomas, Natalie R. (2003). The Medici Women: Gender and Power in Renaissance Florence. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 0754607771.