Pink pigeon

| Pink pigeon | |

|---|---|

| |

| At Birdworld, Surrey, England | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Columbiformes |

| Family: | Columbidae |

| Genus: | Nesoenas |

| Species: | N. mayeri |

| Binomial name | |

| Nesoenas mayeri (Prévost, 1843) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

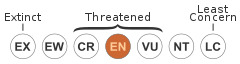

The pink pigeon (Nesoenas mayeri) is a species of pigeon in the family Columbidae endemic to Mauritius. The pink pigeons became nearly extinct in the 1990s and is still very rare. It is the only Mascarene pigeon that has not gone extinct.[2] It was on the brink of extinction in 1991 when only 10 individuals remained, but its numbers have increased due to the efforts of the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust since 1977. While the population remains at below 500 birds as of 2011, the IUCN downlisted the species from Critically endangered to Endangered on the IUCN Red List in 2000.

Taxonomy and evolution

Initially classified as a true pigeon, the pink pigeon was reclassified in a monotypic genus by Tommaso Salvadori. Recent DNA analyses suggest its nearest relative is the geographically close Madagascar turtle dove (Streptopelia picturata), and it has thus been suggested that it be placed in the genus Streptopelia, which mostly contains turtle doves. However, the two species form a distinct group that cannot unequivocally be assigned to either Streptopelia or Columba, and placing both species in Nesoenas may best reflect the fact that they seem to belong to a distinct evolutionary lineage. This classification has been followed here.[3]

Description

An adult pink pigeon is about 36–38 centimetres (14–15 in) from beak to tail and 350 grams in weight. Pink pigeons have pale pinkish-grey plumage on their head, shoulders and underside, along with pink feet. The beak is a dark pink color with a white tip. They have dark brown wings, and a broad, rust-colored tail. Their eyes are dark brown surrounded by an eye-ring of red skin. Newly hatched pigeons have sparse, downy-white feathers and closed eyes.

The voice of the pink pigeon consists of a flight call that is a short, hardened "hoo hoo". The territorial call of the male Pink Pigeon is a series of coos.[4]

Distribution and habitat

The species is endemic to the Mascarene island of Mauritius, a small island to the east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean, and the tiny predator-free island of Isle aux Aigrettes off its est coast.[5] A related subspecies, the Réunion pink pigeon, became extinct on the neighboring Reunion Island around 1700.[6]

As of 2016, there are five locations places where wild populations of the pink pigeon can be found. Four of these locations belong to Black River Gorges National Park and the fifth to Isle aux Aigrettes. All are monitored by the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation. The species is not migratory.[1]

The species prefers upland evergreen forests, but is equally at home in coastal forests as long as the vegetation is native and not dominated by introduced species such as Chinese Guava (Psidium cattleianum) or the privet (Ligustrum robustum). Destruction of such primal forests has been a major reason for its decline.[1]

Behavior and Ecology

The breeding season of the pink pigeon begins in August–September, although birds may breed all year round. The male courts the female with a "step and bow" display. Mating is generally monogamous, with the pair making a flimsy platform nest and defending a small area around it (even though the pigeons initially had no natural predators, one mating pair must defend their territory from other mating pairs). Pink pigeons generally mate for life. The female usually lays 2 white eggs, and incubation duration is 2 weeks. The male incubates during the day, and the female during night and early day. They may breed often, laying 5 to 10 eggs in a season; breeding only pauses in the wild whilst in molt, which may be full or a partial-body/head molt.

There are more males than females in a population due to greater life expectancy of the male (about 5 years more) and in the wild a higher chance of the female being predated. One reason for the difference in life span is that producing eggs is extremely metabolically taxing. And since female birds are nearly constantly producing eggs (even when they're not fertilized, just like domesticated chickens do) this can end up totaling to a large metabolic tax on the female's survival. In captivity, males remain fertile to an age of 17–18 years, females to an age of 10–11 years.

Life History Timeline

- 1 – 7 days: Chicks eyes closed, fed entirely on crop milk.

- 7 – 10 days: Chicks undergo a dietary transformation to solid food.

- 2 – 4 weeks: Chicks fledge, but remain parent-fed.

- 4 - 6/7 weeks: Chicks remain in the nest. After this the chicks leave the nest.

Diet

Feeding in the wild

The pink pigeon is herbivorous, feeding on both exotic and native plants - consuming buds, flowers, leaves, shoots, fruits and seeds. These birds exhibit ground-feeding behaviors, moving and turning over leaf litter in order to find food and grit (for use as gizzard stones). Non-native species like the Chinese Guava have an impact by preventing growth of native trees.

Supplemental feeding

Because the pink pigeon's natural habitat has become degraded, natural food sources have in the past been deemed insufficient to sustain the wild population or allow successful breeding and chick-rearing. The MWF and other organizations are providing supplemental feeding stations that offer diet items like whole wheat. To prevent other bird species from plundering this feed, special feeding platforms have been designed that allow access primarily to pink pigeons only.[7][8]

Conservation

The pink pigeon is currently classified as Endangered by the IUCN, having been downlisted from Critically endangered in 2000, although its population trend as of 2013 is declining again.[1] Due to habitat destruction and introduced predators, the population had dropped to 10 in 1991. The captive breeding and reintroduction program initiated and supported by the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and largely carried out by the WMF has resulted in a population of about 450 in the wild in 2011, as well as a healthy captive population as backup.[1][9]

Several foundations and organizations have contributed to conservation efforts.[10] In addition to direct conservation efforts such as captive breeding, genetic research, and supplementary feeding efforts, more general research on the species may aid in the formation of more applicable conservation actions.[5]

Threats

Habitat degradation, introduced predators, and wildlife disease are the major ongoing threats to the pink pigeon's survival. Only 2% of the native forest remains in Mauritius, with the majority of these remaining forests on upland slopes around the Black River Gorge National Park.[11]

Common predators include the crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis), the small Asian mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus), rats, and feral cats. Invasive plant species such as the Chinese guava and privet dominate native forest plants, preventing their growth. Without these native plant species, the Pink Pigeon finds it hard to locate sound nesting locations or food sources. Extreme weather events such as cyclones may also further the degradation of habitat.[10]

The feeding stations that provide supplementary feed may accelerate the spread of disease between individuals, who congregate at greater than normal numbers at stations. This may apply to trichomonosis, originally brought to Mauritius by introduced pigeons.[1] Feeding stations therefore have to be closely managed to reduce the associated risks.[4]

An ongoing concern faced by the pink pigeon, as by many endangered species that exist in small remnant populations, is inbreeding depression.[1]

In culture

The book Golden Bats and Pink Pigeons by Gerald Durrell describes the conservation efforts.[12]

Mauritius has published a series of postage stamps depicting the pink pigeon.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 BirdLife International (2013). "Nesoenas mayeri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2013: e.T22690392A48001053. Retrieved February 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Hume, J.P. (2011). "Systematics, morphology, and ecology of pigeons and doves (Aves: Columbidae) of the Mascarene Islands, with three new species" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3124: 1–62. ISSN 1175-5326.

- ↑ Johnson, Kevin P.; de Kort, Selvino; Dinwoodey, Karen; Mateman, A. C.; ten Cate, Carel; Lessells, C. M.; Clayton, Dale H. (2001). "A molecular phylogeny of the dove genera Streptopelia and Columba" (PDF). Auk. 118 (4): 874–887. doi:10.2307/4089839.

- 1 2 "Pink Pigeon (Nesoenas mayeri) - BirdLife species factsheet". www.birdlife.org. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- 1 2 G., Jones, C. "Studies on the biology of the pink pigeon Columbia mayeri". ethos.bl.uk. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Nesoenas duboisi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2012: e.T22728712A39190735. Retrieved February 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Edmunds, K.; Bunbury, N.; Sawmy, S.; Jones, C.G.; Bell, D.J. (2008-01-01). "Restoring avian island endemics: use of supplementary food by the endangered Pink Pigeon (Columba mayeri)". Emu. 108 (1): 74–80. doi:10.1071/mu06056.

- ↑ "Pink Pigeon - Nesoenas mayeri". Mauritian Wildlife Foundation.

- ↑ "Mauritius pink pigeon". Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust.

- 1 2 Foundation, Mauritian Wildlife. "Welcome to the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation (MWF) - In The Field - Mauritius - Pink Pigeon". www.mauritian-wildlife.org. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ↑ "Pink pigeon". Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- ↑ Durrell, Gerald (2011). Golden bats and pink pigeons. Pan Macmillan.

Further reading

- Bunbury, Nancy; Stidworthy, Mark F.; Greenwood, Andrew G.; Jones, Carl G.; Sawmy, Shiva; Cole, Ruth; Edmunds, Kelly; Bell, Diana J. (2008). Causes of mortality in free-living Mauritian pink pigeons Columba mayeri, 2002–2006. Endangered Species Research.