Treaty of Warsaw (1920)

The Treaty of Warsaw (also the Polish-Ukrainian or Petlura-Piłsudski Alliance or Agreement) of April 1920 was a military-economical alliance between the Second Polish Republic, represented by Józef Piłsudski, and the Ukrainian People's Republic, represented by Symon Petlura, against Bolshevik Russia. The treaty was signed on 21 April 1920, with a military addendum on 24 April.

The alliance was signed during the Polish-Soviet War, just before the Polish Kiev Offensive. Piłsudski was looking for allies against the Bolsheviks and hoped to create a Międzymorze alliance; Petlura saw the alliance as the last chance to create an independent Ukraine.

The treaty had no permanent impact. The Polish-Soviet War continued and the territories in question were distributed between Russia and Poland in accordance with the 1921 Peace of Riga. Ukrainian territories were split between the Ukrainian SSR in the east and Poland in the west (Galicia and part of Volhynia).

Background

The Polish leader Józef Piłsudski was trying to create a Poland-led alliance of East European countries, the Międzymorze federation, designed to strengthen Poland and her neighbors at the expense of Tsarist Russia, and later of the Russian SFSR and the Soviet Union.[1][2] His plan was however plagued with setbacks, as some of his planned allies refused to cooperate with Poland, and others, while more sympathetic, preferred to avoid conflict with the Bolsheviks.[3] But in April 1920, from a military standpoint, Polish army needed to strike at the Soviets, to disrupt their plans for an offensive of their own.[4] Piłsudski also wanted an independent Ukraine to be a buffer between Poland and Russia rather than seeing Ukraine again dominated by Russia right at the Polish border.[5] Piłsudski, who argued that "There can be no independent Poland without an independent Ukraine", may have been more interested in Ukraine being split from Russia than he was in Ukrainians' welfare.[6] As such, Piłsudski turned to Petlura, whom he originally had not considered high on his planned allies list.[7]

A Ukrainian delegation could not gain recognition for Ukraine as an independent state at the Treaty of Versailles at the end of the First World War, and the Ukrainian dream of independence was also plagued with setbacks, with Ukrainian lands becoming a warzone between various local and foreign factions vying for their control. The Ukrainian People's Republic, led by Petlura, suffered mounting attacks on its territory since early 1919, and by April 1920 most of Ukrainian territory was outside its control.[8]

In such conditions, Józef Piłsudski had little difficulty in convincing Petlura to join the alliance with Poland despite recent conflict between the two nations that had been settled in favour of Poland the previous year.[3]

The treaty

The treaty was signed on 21 April in Warsaw[7] (it should be noted that some sources give the dates 20 and 22 April for the signing of the treaty). In exchange for agreeing to a border along the Zbruch River, recognizing the recent Polish territorial gains in western Ukraine (Article II)[3][9] (obtained by the Poland's defeating the Ukrainian attempt to create another Ukrainian state in Volhynia and Galicia, territories with mixed Ukrainian-Polish population), Poland recognized the Ukrainian People's Republic as an independent state (Article I) with borders as defined by Articles II and III and under ataman Petlura's leadership.[7]

A separate provision in the treaty prohibited both sides from concluding any international agreements against each other (Article IV).[10] Ethnic Poles within the Ukrainian border, and ethnic Ukrainians within the Polish border, were guaranteed the same rights within their states (Article V).[11] Unlike their Russian counterparts, whose lands were to be distributed among the peasants, Polish landlords in Ukraine were accorded special treatment[10] until a future legislation would be passed by Ukraine that would clarify the issue of Polish landed property in Ukraine (Article VI).[7] Further, an economic treaty was drafted, significantly tying Polish and Ukrainian economies; Ukraine was to grant significant concessions to the Poles and the Polish state.[3][7]

The treaty was followed by a formal military alliance signed by general Volodymyr Sinkler and Walery Sławek on 24 April. Petlura was promised military help in regaining the control of Bolshevik-occupied territories with Kiev, where he would again assume the authority of the Ukrainian People's Republic.[4] The Ukrainian republic was to subordinate its military to Polish command and provide the joint armies with supplies on Ukrainian territories; the Poles in exchange promised to provide equipment for the Ukrainians.[3][7]

On the same day as the military alliance was signed (24 April), Poland and UPR forces began the Kiev Operation, aimed at securing the Ukrainian territory for Petlura's government thus creating a buffer for Poland that would separate it from Russia. Sixty-five thousand Polish and fifteen thousand Ukrainian soldiers[12] took part in the initial expedition. After winning the battle in the south, the Polish General Staff planned a speedy withdrawal of the 3rd Army and strengthening of the northern front in Belarus where Piłsudski expected the main battle with the Red Army to take place. The Polish southern flank was to be held by Polish-allied Ukrainian forces under a friendly government in Ukraine.

Importance

For Piłsudski, this alliance gave his campaign for the Międzymorze federation the legitimacy of joint international effort,[7] secured part of the Polish eastward border, and laid a foundation for a Polish dominated Ukrainian state between Russia and Poland.[3] For Petlura, this was a final chance to preserve the statehood and, at least, the theoretical independence of the Ukrainian heartlands, even while accepting the loss of Western Ukrainian lands to Poland.[13]

Aftermath

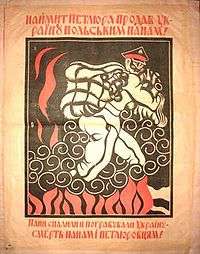

Both Piłsudski and Petlura were criticized by other factions within their governments and nations. Piłsudski faced stiff opposition from Dmowski's National Democrats who opposed Ukrainian independence; Petlura, in turn, was criticized by many Ukrainian politicians for entering a pact with the Poles and giving up on Western Ukraine.[14] Mykhailo Hrushevsky, the highly respected chairman of the Central Council, also condemned the alliance with Poland and Petlura's claim to have acted on the behalf of the UPR.[14] In general, many Ukrainians viewed a union with Poles with great suspicion,[5][13] especially in the view of historically difficult relationships between the nations, and the alliance received an especially dire reception from Galicia Ukrainians who viewed it as their betrayal;[15] their attempted state, the West Ukrainian People's Republic, had been defeated by July 1919 and was now to be incorporated into Poland. The Western Ukrainian political leader, Yevhen Petrushevych, who expressed fierce opposition to the alliance, left for exile in Vienna. The remainder of the Ukrainian Galician Army, the Western Ukrainian state's defence force, still counted 5,000 able fighters though devastated by a typhoid epidemic, joined the Bolsheviks on 2 February 1920 as the transformed Red Ukrainian Galician Army.[16][17] Later, the Galician forces would turn against the Communists and join Petliura's forces when sent against them, resulting in mass arrests and disbandment of the Red Galician Army.[10]

On April 26, in his "Call to the People of Ukraine", Piłsudski assured that "the Polish army would only stay as long as necessary until a legal Ukrainian government took control over its own territory".[18] Despite this, many Ukrainians were just as anti-Polish as anti-Bolshevik,[5] and resented the Polish advance,[4] which many viewed as just a new variety of occupation[19] considering previous defeat in the Polish-Ukrainian War.[20] Thus, Ukrainians also actively fought the Polish invasion in Ukrainian formations of the Red Army.[17] Some scholars stress the effects of Soviet propaganda in encouraging negative Ukrainian sentiment towards the Polish operation and Polish-Ukrainian history in general.[4]

The alliance between Piłsudski and Petliura resulted in 15,000 allied Ukrainian troops supporting Poles at the beginning of the campaign,[21] increasing to 35,000 through recruitment and desertion from the Soviet side during the war.[21] This number, however, was much smaller than expected, and the late alliance with Poland failed to secure Ukraine's independence, as Petlura did not manage to gather any significant forces to help his Polish allies.

On 7 May, during the course of the Kiev Offensive, the Pilsudski-Petliura alliance took the city. Anna M. Cienciala writes: "However, the expected Ukrainian uprising against the Soviets did not take place. Ukraine was ravaged by war; also, most of the people were illiterate and had not developed their own national consciousness. Finally, they distrusted the Poles, who had formed a large part of the landowning class in Ukraine up to 1918."[4]

The divisions within the Ukrainian factions themselves, with many opposing Poles just as they opposed the Soviets, further reduced the recruitment to the pro-Polish Petlura forces. In the end, Petlura forces were unable to protect the Polish southern flank and stop the Soviets, as Piłsudski hoped; Poles at that time were falling back before the Soviet counteroffensive and were unable to protect Ukraine from the Soviets by themselves.

The Soviets retook Kiev in June. Petlura's remaining Ukrainian troops were defeated by the Soviets in November 1920,[22] and by that time the Poles and the Soviets had already signed an armistice and were negotiating a peace agreement. After the Polish-Soviet Peace of Riga next year, Ukrainian territory found itself split between the Ukrainian SSR in the east, and Poland in the west (Galicia and part of Volhynia). Piłsudski felt the agreement was a shameless and short-sighted political calculation. Allegedly, having walked out of the room, he told the Ukrainians waiting there for the results of the Riga Conference: "Gentlemen, I deeply apologize to you".[23][24] Over the coming years, Poland would provide some aid to Petlura's supporters in an attempt to destabilize Soviet Ukraine (see Prometheism), but it could not change the fact that Polish-Ukrainian relations would continue to steadily worsen over the interwar period.[15][25] One month before his death Pilsudski told his aide: "My life is lost. I failed to create the free from the Russians Ukraine"[26]

Notes

- ↑ "Although the Polish premier and many of his associates sincerely wanted peace, other important Polish leaders did not. Josef Pilsudski, chief of state and creator of Polish army, was foremost among the latter. Pilsudski hoped to build not merely a Polish nation state but a greater federation of peoples under the aegis of Poland which would replace Russia as the great power of Eastern Europe. Lithuania, Belorussia and Ukraine were all to be included. His plan called for a truncated and vastly reduced Russia, a plan which excluded negotiations prior to military victory."

Richard K Debo, Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918-192, Google Print, p. 59, McGill-Queen's Press, 1992, ISBN 0-7735-0828-7. - ↑ "Pilsudski's program for a federation of independent states centered on Poland; in opposing the imperial power of both Russia and Germany it was in many ways a throwback to the romantic Mazzinian nationalism of Young Poland in the early nineteenth century. But his slow consolidation of dictatorial power betrayed the democratic substance of those earlier visions of national revolution as the path to human liberation"

James H. Billington, Fire in the Minds of Men, p. 432, Transaction Publishers, ISBN 0-7658-0471-9 - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Richard K Debo, Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918-1921, pp. 210-211, McGill-Queen's Press, 1992, ISBN 0-7735-0828-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 THE REBIRTH OF POLAND. University of Kansas, lecture notes by professor Anna M. Cienciala, 2004. Last accessed on 2 June 2006.

- 1 2 3 Ronald Grigor Suny, The Soviet Experiment: Russia, the USSR, and the Successor States, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-508105-6, Google Print, p.106

- ↑ "The newly founded Polish state cared much more about the expansion of its borders to the east and southeast ("between the seas") than about helping the dying [Ukrainian] state of which Petlura was de facto dictator. ("A Belated Idealist." Zerkalo Nedeli (Mirror Weekly), May 22–28, 2004. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.)

Piłsudski is quoted to have said: "After the Polish independence we will see about Poland's size". (ibid) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Davies, White Eagle..., Polish edition, p.99-103

- ↑ Watt, Richard (1979). Bitter Glory: Poland and its Fate 1918-1939. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 119. ISBN 0-671-22625-8.

- ↑ Alison Fleig Frank (1 July 2009). Oil Empire: Visions of Prosperity in Austrian Galicia. Harvard University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-674-03718-2.

- 1 2 3 Ukraine: a concise encyclopedia, pp. 766-767, edited by Volodymyr Kubiyovych, Ukrainian National Association, University of Toronto Press, 1963-1971, 2 v., LCCN 63-23686

- ↑ Watt, Richard (1979). Bitter Glory: Poland and its Fate 1918-1939. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 109. ISBN 0-671-22625-8.

- ↑ Subtelny, Orest (2000). "Twentieth Century Ukraine: The Ukrainian Revolution: Petlura's alliance with Poland". Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 375. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- 1 2 "In September 1919 the armies of the Ukrainian Directory in Podolia found themselves in the "death triangle". They were squeezed between the Red Russians of Lenin and Trotsky in the north-east, White Russians of Denikin in south-east and the Poles in the West. Death were looking into their eyes. And not only to the people but to the nascent Ukrainian state. Therefore, the chief ataman Petlura had no choice but to accept the union offered by Piłsudski, or, as an alternative, to capitulate to the Bolsheviks, as Volodymyr Vinnychenko or Mykhailo Hrushevsky did at the time or in a year or two. The decision was very hurtful. The Polish Szlachta was a historic enemy of the Ukrainian people. A fresh wound was bleeding, the West Ukrainian People's Republic, as the Pilsudchiks were suppressing the East Galicians at that very moment. However, Petlura agreed to peace and the union, accepting the Ukrainian-Polish border, the future Soviet-Polish one. It's also noteworthy that Piłsudski also obtained less territories than offered to him by Lenin, and, in addition, the war with immense Russia. The Dnieper Ukrainians then were abandoning their brothers, the Galicia Ukrainians, to their fate. However, Petlura wanted to use his last chance to preserve the statehood - in the union with the Poles. Attempted, however, without luck."

(Russian) (Ukrainian) Oleksa Pidlutskyi, Postati XX stolittia, (Figures of the 20th century), Kiev, 2004, ISBN 966-8290-01-1, LCCN 2004-440333. Chapter "Józef Piłsudski: The Chief who Created Himself a State" reprinted in Zerkalo Nedeli (the Mirror Weekly), Kiev, February 3–9, 2001, in Russian and in Ukrainian. - 1 2 Prof. Ruslan Pyrig, "Mykhailo Hrushevsky and the Bolsheviks: the price of political compromise", Zerkalo Nedeli, September 30 - October 6, 2006, available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- 1 2 Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-10586-X Google Books, p.139

- ↑ Червона Українська Галицька Армія (Red Ukrainian Galician Army), in Енциклопедія українознавства (Encyclopedia of the knowledge about Ukraine), 2 volumes, edited by Volodymyr Kubiyovych, Lviv, Distributed by East View Publications, 1993, ISBN 5-7707-4048-5

- 1 2 Peter Abbot."Ukrainian Armies 1914-55", Chapter "Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, 1917-21", Osprey, 2004, ISBN 1-84176-668-2

- ↑ (Polish), Włodzimierz Bączkowski, Włodzimierz Bączkowski - Czy prometeizm jest fikcją i fantazją?, Ośrodek Myśli Politycznej (quoting full text of "odezwa Józefa Piłsudskiego do mieszkańców Ukrainy"). Last accessed on 25 October 2006.

- ↑ Tadeusz Machalski, then a captain, (the future military attache to Ankara) wrote in his diary: "Ukrainian people, who saw in their capital an alien general with the Polish army, instead of Petlura leading his own army, didn't view it as the act of liberation but as a variety of a new occupation. Therefore, the Ukrainians, instead of enthusiasm and joy, watched in gloomy silence and instead of rallying to arms to defend the freedom remained the passive spectators".

Oleksa Pidlutskyi, ibid - ↑ "In practice, [Pilsudski] was engaged in a process of conquest that was bitterly resisted by Lithuanians and Ukrainians (except the latter's defeat by the Bolsheviks left them with no one else to turn but Pilsudski)."

Roshwald, Aviel (2001). https://books.google.com/books?id=qPyer6Pks0oC&pg=PA164&lpg=PA164&sig=O-9FXzZz2mDsX8Gm9U7QwcCYO2s|chapterurl=missing title (help). Ethnic Nationalism and the Fall of Empires: Central Europe, the Middle East and Russia, 1914-1923. Routledge (UK). ISBN 0-415-24229-0. - 1 2 Subtelny, O. (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 375.

- ↑ Davies, White Eagle..., Polish edition, p.263

- ↑ Jerzy Surdykowski (2001). "Ja was przepraszam panowie, czyli Polska a Ukraina i inni wpóltowarzysze niedoli". Duch Rzeczypospolitej (in Polish). Warsaw: Wydawictwa Naukowe PWN. p. 335. ISBN 83-01-13403-8.

- ↑ Jan Jacek Bruski (August 2002). "Sojusznik Petlura". Wprost (in Polish). 1029 (2002–08–18). Retrieved 2006-09-28.

- ↑ Timothy Snyder, Covert Polish missions across the Soviet Ukrainian border, 1928-1933 (p.55, p.56, p.57, p.58, p.59, in Cofini, Silvia Salvatici (a cura di), Rubbettino, 2005). Full text in PDF

Timothy Snyder, Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artist's Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine, Yale University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-300-10670-X, (p.41, p.42, p.43) - ↑ <(Russian) (Ukrainian) Oleksa Pidlutskyi, Postati XX stolittia, (Figures of the 20th century), Kiev, 2004, ISBN 966-8290-01-1, LCCN 2004-440333. Chapter "Józef Piłsudski: The Chief who Created Himself a State" reprinted in Zerkalo Nedeli (the Mirror Weekly), Kiev, February 3–9, 2001, in Russian and in Ukrainian.

See also

External links

Further reading

- Korzeniewski, Bogusław; THE RAID ON KIEV IN POLISH PRESS PROPAGANDA. Humanistic Review (01/2006),

- Review of The Ukrainian-Polish Defensive Alliance, 1919-1921: An Aspect of the Ukrainian Revolution by Michael Palij; Author(s) of Review: Anna M. Cienciala; The American Historical Review, Vol. 102, No. 2 (Apr., 1997), p. 484 ()

- Szajdak, Sebastian, Polsko-ukraiński sojusz polityczno-wojskowy w 1920 roku (The Polish-Ukrainian Political-Military Alliance of 1920), Warsaw, Rytm, 2006, ISBN 83-7399-132-8.