Galicia (Eastern Europe)

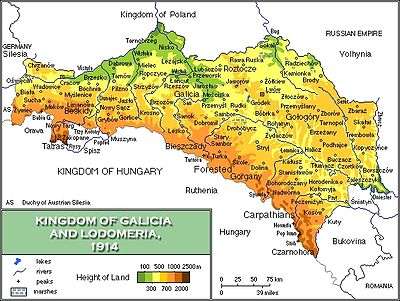

| Galicia | |

|---|---|

|

| |

|

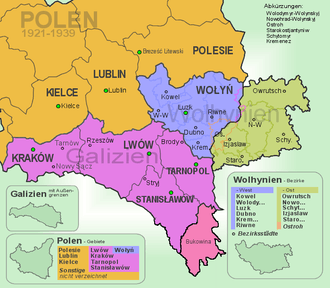

Galicia in relation to Volhynia (east and west) between the two world wars |

Galicia (Ukrainian: Галичина, Halychyna; Polish: Galicja; Czech: Halič; German: Galizien; Hungarian: Galícia/Kaliz/Gácsország/Halics; Romanian: Galiția/Halici; Russian: Галиция, Galitsiya; Rusyn: Галичина, Halychyna; Slovak: Halič; Yiddish: גאַליציע, Galitsye) is a historical and geographic region in Central-Eastern Europe,[1][2][3] once a small kingdom that straddled the modern-day border between Poland and Ukraine. The area, which is named after the medieval city of Halych,[4][5][6] was first mentioned in Hungarian historical chronicles in the year 1206 as Galiciæ.[7][8]

The nucleus of historic Galicia lies within the modern regions of western Ukraine: Lviv, Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk near Halych.[9] In the 18th century, territories that later became part of the modern Polish regions of Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Subcarpathian Voivodeship and Silesian Voivodeship were added to Galicia.

There is considerable overlap between Galicia and south-west Ruthenia (Rusyn: Русь Rus', Ukrainian: Русь Rus', Slovakian: Rus), especially a cross-border region (centred on Zakarpattia Oblast, the Transcarpathian Region of present-day Ukraine) that is inhabited by various nationalities, including the Rusyn minority. In this modern sense, "Ruthenia" straddles western Ukraine, Poland and Slovakia.

Origins and variations of the name

In the 13th century, King Andrew II of Hungary claimed the title Rex Galiciae et Lodomeriae ("King of Galicia and Lodomeria")[7][10][11] – a Latinised version of the Slavic names Halych and Volodymyr, the major cities of the principality of Halych-Volhynia, which the Hungarians ruled from 1214 to 1221. Halych-Volhynia cut a swathe as a mighty principality under the reign of Roman the Great in 1170–1205. After the expulsion of the Hungarians in 1221, Ruthenians took back rule of the area. Roman's son Daniel of Galicia was crowned king of Halych-Volhynia. He founded Lviv (Leopolis), named in honour of his son Leo I, who later moved the capital from Halych to Lviv.

The Ukrainian name Halych (Галич) (Halicz in Polish, Галич in Russian, Galic in Latin) comes from the Khwalis or Kaliz who occupied the area from the time of the Magyars. They were also called Khalisioi in Greek, and Khvalis (Хваліс) in Ukrainian. Some historians[lower-alpha 1] speculated it had to do with a group of people of Thracian origin (i.e. Getae)[12] that during the Iron Age moved into the area after Roman conquest of Dacia and may have formed the Lypytsia culture with the arrived Venedi people who moved in the region at the end of Le Tene period (La Tene culture).[12] The Lypytsia culture supposedly replaced the existing Thracian Hallstatt (see Thraco-Cimmerian) and Vysotske cultures.[12] Connection with Celtic peoples supposedly explains its relation to many similar place names found across Europe and Asia Minor, such as ancient Gallia or Gaul (modern France, Belgium, and northern Italy) and Galatia (modern Turkey), the Iberian Peninsula's Galicia, and Romanian Galaţi.[12] Others assert that the name has Slavic origins – from halytsa, meaning "a naked (unwooded) hill", or from halka which means "jackdaw". The jackdaw was used as a charge in the city's coat of arms and later also in the coat of arms of Galicia. The name, however, predates the coat of arms, which may represent canting or simply folk etymology.

Although the Hungarians were driven out from Halych-Volhynia by 1221, Hungarian kings continued to add Galicia et Lodomeria to their official titles. In 1527, the Habsburgs inherited those titles, together with the Hungarian crown. In 1772, Empress Maria Theresa, Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary, decided to use those historical claims to justify her participation in the first partition of Poland. In fact, the territories acquired by Austria did not correspond exactly to those of former Halych-Volhynia. Volhynia, including the city of Volodymyr-Volynskyi (Włodzimierz Wołyński) – after which Lodomeria was named – was taken by Russia, not Austria. On the other hand, much of Lesser Poland – Nowy Sącz and Przemyśl (1772–1918), Zamość (1772–1809), Lublin (1795–1809), Kraków (1846–1918) – did become part of Austrian Galicia. Moreover, despite the fact that the claim derived from the historical Hungarian crown, Galicia and Lodomeria was not officially assigned to Hungary, and after the Ausgleich of 1867, it found itself in Cisleithania, or the Austrian-administered part of Austria-Hungary.

The full official name of the new Austrian province was Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria with the Duchies of Auschwitz and Zator. After the incorporation of the Free City of Kraków in 1846, it was extended to Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, and the Grand Duchy of Kraków with the Duchies of Auschwitz and Zator (German: Königreich Galizien und Lodomerien mit dem Großherzogtum Krakau und den Herzogtümern Auschwitz und Zator).

Each of those entities was formally separate; they were listed as such in the Austrian emperor's titles, each had its distinct coat-of-arms and flag. For administrative purposes, however, they formed a single province. The duchies of Auschwitz (Oświęcim) and Zator were small historical principalities west of Kraków, on the border with Prussian Silesia. Lodomeria, under the name Volhynia, was not ruled by Austria but by the Russian Empire.

Ethnographic groups of Polish Galicia

- Mountain Dwellers (larger kinship group): Żywczaki or Gorals of Żywiec (pl: górale żywieccy), Babiogórcy or Gorals of Babia Góra, Gorals of Rabka or Zagórzanie, Kliszczaki, Gorals in Podhale (pl: górale podhalańscy), Gorals of Nowy Targ or Nowotarżanie, Górale pienińscy or Gorals of Pieniny and Górale sądeccy (Gorals of Nowy Sącz), Gorals of Spisz or Gardłaki, Kurtacy or Czuchońcy (Lemkos, Rusnaks), Boykos (Werchowyńcy), Tucholcy, Hutsuls (Czarnogórcy).

- Dale Dwellers (larger kinship group): Krakowiacy, Mazury, Grębowiacy (Lesowiacy or Borowcy), Głuchoniemcy, Bełżanie, Bużanie (Łopotniki, Poleszuki), Opolanie, Wołyniacy, Pobereżcy or Nistrowianie.[13]

History

In Roman times, the region was populated by various tribes of Celto-Germanic admixture, including Celtic-based tribes – like the Galice or "Gaulics" and Bolihinii or "Volhynians" – the Lugians and Cotini of Celtic, Vandals and Goths of Germanic origins (the Przeworsk and Púchov cultures). During the Great Migration period of Europe (coinciding with the fall of the Roman Empire), a variety of nomadic groups invaded the area.[14][15] Overall, Slavs (both West and East Slavs, including Lendians as well as Rusyns) came to dominate the Celtic-German population.

In the 12th century, a Rurikid Principality of Halych (Halicz, Halics, Galich, Galic) formed there, which merged in the end of the century with the neighbouring Volhynia into the Principality of Halych Volhynia. Galicia and Volhynia had originally been two separate Rurikid principalities, assigned on a rotating basis to younger members of the Kievan dynasty. The line of Prince Roman the Great of Vladimir-in-Volhynia had held the principality of Volhynia, while the line of Yaroslav Osmomysl held the Principality of Halych (later adopted as Galicia). Galicia–Volhynia was created following the death in 1198[16] or 1199[17] (and without a recognised heir in the paternal line) of the last Prince of Galicia, Vladimir II Yaroslavich; Roman acquired the Principality of Galicia and united his lands into one state. Roman's successors would mostly use Halych (Galicia) as the designation of their combined kingdom. In Roman's time Galicia–Volhynia's principal cities were Halych and Volodymyr-in-Volhynia. In 1204, Roman captured Kiev, while being in alliance with Poland, he signed a peace treaty with Hungary and established diplomatic relations with the Byzantine Empire.[18]

In 1205, Roman turned against his Polish allies, leading to a conflict with Leszek the White and Konrad of Masovia. Roman was subsequently killed in the Battle of Zawichost (1205), and his dominion entered a period of rebellion and chaos. Thus weakened, Galicia–Volhynia became an arena of rivalry between Poland and Hungary. King Andrew II of Hungary styled himself rex Galiciæ et Lodomeriæ, Latin for "king of Galicia and Vladimir [in-Volhynia]", a title that later was adopted in the Habsburg Empire. In a compromise agreement made in 1214 between Hungary and Poland, the throne of Galicia–Volhynia was given to Andrew's son, Coloman of Lodomeria.

In 1352, when the principality was divided between the Polish Kingdom and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the territory became subject to the Polish Crown. With the Union of Lublin in 1569 Poland and Lithuania merged to form the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which lasted for 200 years until conquered and divided up by Russia, Prussia, and Austria.

In 1772 with the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the south-eastern part of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was awarded to the Habsburg Empress Maria-Theresa, whose bureaucrats christened it the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, after one of the titles of the princes of Hungary, although its borders coincided but roughly with those of the former medieval principality.[19] Known informally as Galicia, it became the largest, most populous, and northernmost province of the Austrian Empire until the dissolution of that monarchy at the end of World War I in 1918, when it ceased to exist as a geographic entity.

During the First World War, Galicia saw heavy fighting between the forces of Russia and the Central Powers. The Russian forces overran most of the region in 1914 after defeating the Austro-Hungarian army in a chaotic frontier battle in the opening months of the war.[20] They were in turn pushed out in the spring and summer of 1915 by a combined German and Austro-Hungarian offensive.

In 1918, Western Galicia became a part of the restored Republic of Poland, which absorbed the Lemko-Rusyn Republic. The local Ukrainian population briefly declared the independence of Eastern Galicia as the "West Ukrainian People's Republic". During the Polish-Soviet War the Soviets tried to establish the puppet-state of the Galician SSR in East Galicia, the government of which after a couple of months was liquidated.

The fate of Galicia was settled by the Peace of Riga on March 18, 1921, attributing Galicia to the Second Polish Republic. Although never accepted as legitimate by some Ukrainians, it was internationally recognized on May 15, 1923.[21]

The Ukrainians of the former eastern Galicia and the neighbouring province of Volhynia, made up about 12% of the Second Polish Republic population, and were its largest minority. As Polish government policies were unfriendly towards minorities, tensions between the Polish government and the Ukrainian population grew, eventually giving rise to the militant underground Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists.

People

In 1773, Galicia had about 2.6 million inhabitants in 280 cities and market towns and approximately 5,500 villages. There were nearly 19,000 noble families, with 95,000 members (about 3% of the population). The serfs accounted for 1.86 million, more than 70% of the population. A small number were full-time farmers, but by far the overwhelming number (84%) had only smallholdings or no possessions.

Galicia had arguably the most ethnically diverse population of all the countries in the Austrian monarchy, consisting mainly of Poles and "Ruthenians";[22] the peoples known later as Ukrainians and Rusyns, as well as ethnic Jews, Germans, Armenians, Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, Roma and others. In Galicia as a whole, the population in 1910 was estimated to be 45.4% Polish, 42.9% Ukrainian, 10.9% Jewish, and 0.8% German.[23] This population was not evenly distributed. The Poles lived mainly in the west, with the Ukrainians predominant in the eastern region ("Ruthenia"). At the turn of the twentieth century, Poles constituted 78.7% of the whole population of Western Galicia, Ukrainians 13.2%, Jews 7.6%, Germans 0.3%, and others 0.2%. The respective data for Eastern Galicia show the following numbers: Ukrainians 64.5%, Poles 21.0%, Jews 13.7%, Germans 0.3%, and others 0.5%.[24][25] Of the 44 administrative divisions of Austrian eastern Galicia, Lviv (Polish: Lwów, German: Lemberg) was the only one in which Poles made up a majority of the population[26]

Linguistically, the Polish language was predominant in Galicia. According to the 1910 census 58.6% of the combined population of both western and eastern Galicia spoke Polish as its mother tongue compared to 40.2% who spoke the Ukrainian language.[27] The number of Polish-speakers may have been inflated because Jews were not given the option of listing Yiddish as their language.[28]

The Jews of Galicia had immigrated in the Middle Ages from Germany. German-speaking people were more commonly referred to by the region of Germany where they originated (such as Saxony or Swabia). For inhabitants who spoke different native languages, e.g. Poles and Ruthenians, identification was less problematic, but widespread multilingualness blurred the borders again.

It is, however, possible to make a clear distinction in religious denominations: Poles were Roman Catholic, the Ruthenians belonged to the Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church (now split into several sui juris Catholic churches, the largest of which is the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church). The Jews represented the third largest religious group. Galicia was the center of the branch of Orthodox Judaism known as Hasidism.

Economy

The new state borders had cut Galicia off from many of its traditional trade routes and markets of the Polish sphere, resulting in stagnation of economic life and decline of Galician towns. Lviv lost its status as a significant trade centre. After a short period of limited investments, the Austrian government started a fiscal exploitation of Galicia and drained the region of manpower through conscription to the imperial army. The Austrians decided that Galicia should not develop industrially but remain an agricultural area that would serve as a supplier of food products and raw materials to other Habsburg provinces. New taxes were instituted, investments were discouraged, and cities and towns were neglected.[29][30][31] The result was significant poverty in Austrian Galicia.[32][33] Galicia was the poorest province of Austro-Hungary,[34] [35] and according to Norman Davies, could be considered "the poorest province in Europe".[33]

Oil and natural gas industry

Near Drohobych and Boryslav in Galicia, significant oil reserves were discovered and developed during the mid 19th and early 20th centuries.[36][37] The first European attempt to drill for oil was in Bóbrka in western Galicia in 1854.[36][37] By 1867, a well at Kleczany, in Western Galicia, was drilled using steam to about 200 meters.[36][37] On December 31, 1872, a railway line linking Borysław (now Boryslav) with the nearby city of Drohobycz (now Drohobych) was opened. British engineer John Simeon Bergheim and Canadian William Henry McGarvey came to Galicia in 1882.[38][lower-alpha 2] In 1883, their company, MacGarvey and Bergheim, bored holes of 700 to 1,000 meters and found large oil deposits.[36] In 1885, they renamed their oil developing enterprise the Galician-Karpathian Petroleum Company (German: Galizisch-Karpathische Petroleum Aktien-Gesellschaft), headquartered in Vienna, with McGarvey as the chief administrator and Bergheim as field engineer,[lower-alpha 3] and built a huge refinery at Maryampole near Gorlice, in the southeast corner of Galicia.[38] Considered the biggest, most efficient enterprise in Austro-Hungary, Maryampole was built in six months and employed 1000 men.[38][lower-alpha 4] Subsequently, investors from Britain, Belgium, and Germany established companies to develop the oil and natural gas industries in Galicia.[36] This influx of capital caused the number of petroleum enterprises to shrink from 900 to 484 by 1884, and to 285 companies manned by 3,700 workers by 1890.[36] However, the number of oil refineries increased from thirty-one in 1880 to fifty-four in 1904.[36] By 1904, there were thirty boreholes in Borysław of over 1,000 meters.[36] Production increased by 50% between 1905 and 1906 and then trebled between 1906 and 1909 because of unexpected discoveries of vast oil reserves of which many were gushers.[39] By 1909, production reached its peak at 2,076,000 tons or 4% of worldwide production.[36][37] Often called the "Polish Baku", the oil fields of Borysław and nearby Tustanowice accounted for over 90% of the national oil output of the Austria-Hungary Empire.[36][39][40] From 500 residents in the 1860s, Borysław had swollen to 12,000 by 1898.[39] At the turn of the century, Galicia was ranked fourth in the world as an oil producer.[36][lower-alpha 5] This significant increase in oil production also caused a slump in oil prices.[39] A very rapid decrease in oil production in Galicia occurred just before the Balkans conflicts.

Galicia was the Central Powers only major domestic source of oil during the Great War.[39]

See also

- Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

- Subdivisions of Galicia

- Bukovina

- West Ukrainian People's Republic

- Galician Soviet Socialist Republic

- Halych-Volhynia

- History of the Jews in Galicia (Eastern Europe)

- Lesser Poland

- List of rulers of Halych and Volhynia

- List of Galician rulers

- List of towns of the former Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

- Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

- Distrikt Galizien

Notes

- ↑ Encyclopediaofukraine.com: Volodymyr Kubiyovych, Yaroslav Pasternak, Illya Vytanovych, Arkadiy Zhukovsky.[12]

- ↑ William McGarvey helped develop a rig in the 1860s or 70s which made his Canadian drilling technology and Canadian drillers famous around the world. John Simon Bergheim and William Henry McGarvey had unsuccessfully searched for oil in Germany under the Continental Oil Company of which McGarvey was the director. They left Germany and began their first drilling in Galicia during 1882 under the company name of MacGarvey and Bergheim.[38]

- ↑ Just after the turn of the century, Bergheim was killed in a taxicab accident in London, England, leaving McGarvey to carry on alone.[38]

- ↑ Later, Bergheim and McGarvey bought a number of small oil-producing and refining operations and acquired the Apollo Oil Company of Budapest.[38]

- ↑ In 1909, first in the world for oil production was the United States with 183,171,000 barrels, the Russian Empire was second with 65,970,000 barrels, and the Austria-Hungary Empire was third with 14,933,000 barrels per year due to its significant oil reserves discoveries between 1905 and 1909.[39][41]

References

- ↑ Eleonora Narvselius (April 5, 2012). Narratives about (Be)longing, Ambiguity, and Cultural Colonization (Google eBook). Ukrainian Intelligentsia in Post-Soviet L'viv: Narratives, Identity, and Power. Lexington Books. p. 293. ISBN 0739164708. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ↑ Larry Wolff (January 9, 2012). Mythology and Nostalgia: A Matter of Simple Relativity (Google eBook). The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture. Stanford University Press. p. 411. ISBN 0804774293. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ↑ Paul R. Magocsi (2002). Jews and Armenians in Central Europe, ca. 1900 (Google Books). Historical Atlas of Central Europe. University of Toronto Press. p. 124. ISBN 0802084869. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ↑ "European Kingdoms - Eastern Europe - Galicia". The History Files. Kessler Associates. Retrieved 2014-12-13.

- ↑ History of Galicia

- ↑ Ukrainian Historical Glossary

- 1 2 "Rex+Galiciae+et+Lodomeriae" Die Oesterreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild, Volume 19 (in German). Austria: K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei. 1898. p. 165. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

Um welchen Preis er dies that, wird nicht überliefert, aber seit dieser Zeit, das ist seit dem Jahre 1206 findet sich in seinen Urkunden der Titel: "Rex Galiciae et Lodomeriae"

- ↑ Martin Dimnik (12 June 2003). The Dynasty of Chernigov, 1146–1246. Cambridge University Press. pp. 266–. ISBN 978-1-139-43684-7. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ↑ Wilson, Andrew (2006). Ukraine's Orange Revolution. Andrew Wilson (historian): Yale University Press. p. 34. ISBN 0-300-11290-4.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 441.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 317.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Galicia and Lodomeria at the Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- ↑ SGKP tom II. str. 459

- ↑ Tadeusz Sulimirski, The Sarmatians, vol. 73 in series "Ancient People and Places", London: Thames & Hudson, 1970.

- ↑ Dr. Samar Abbas, Bhubaneshwar, India. "Samar Abbas, ''Common Origin of Croats, Serbs and Jats'', The symposium proceedings "Old Iranian Origins of Croats", Zagreb, 1998". Iranchamber.com. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ↑ Dimnik, Martin (2003). The Dynasty of Chernigov - 1146-1246. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. (Chronological table of events) xxviii. ISBN 978-0-521-03981-9.

- ↑ Charles Cawley (2008-05-19). "Russia, Rurikids – Chapter 3: Princes of Galich B. Princes of Galich 1144-1199". Medieval Lands. Foundation of Medieval Genealogy. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ↑ Roman Mstyslavych - Encyclopaedia of Ukraine

- ↑ Larry Wolff, The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture (Sanford University Press, 2012), p. 1

- ↑ Buttar, Prit. Collision of Empires: The War on the Eastern Front in 1914. Oxford, UK; New York, NY: Osprey Publishing, 2016. ISBN 9781782006480

- ↑ French: Les Alliés reconnaissent à la Pologne la possession de la Galicie, Chronologie des civilisations, Jean Delorme, Paris, 1956.

- ↑ Magocsi, Paul R. (2002). The Roots of Ukrainian Nationalism: Galicia as Ukraine's Piedmont. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 57.

- ↑ Paul Robert Magocsi. (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University ofToronto Press. Pg. 424.

- ↑ Piotr Eberhardt. Ethnic groups and population changes in twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: history, data, analysis. M.E. Sharpe, 2003. pp.92–93. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5

- ↑ Timothy Snyder. (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 123

- ↑ Timothy Snyder. (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 134

- ↑ Anstalt G. Freytag & Berndt (1911). Geographischer Atlas zur Vaterlandskunde an der österreichischen Mittelschulen. Vienna: K. u. k. Hof-Kartographische. "Census December 31st 1910"

- ↑ Timothy Snyder. (2003).The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press, pg. 134

- ↑ P. R. Magocsi. (1983). Galicia: A Historical Survey and Bibliographic Guide. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies,Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. p. 99

- ↑ P. Wandycz. (1974). The lands of partitioned Poland, 1795-1918. A History of East Central Europe. University of Washington Press. p. 12

- ↑ K. Stauter-Halsted. (2005). The Nation In The Village: The Genesis Of Peasant National Identity In Austrian Poland, 1848-1914. Cornell University Press. p. 24

- ↑ Keely Stauter-Halsted (28 February 2005). The Nation In The Village: The Genesis Of Peasant National Identity In Austrian Poland, 1848-1914. Cornell University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8014-8996-9. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- 1 2 Norman Davies (31 May 2001). Heart of Europe:The Past in Poland's Present. Oxford University Press. pp. 331–. ISBN 978-0-19-164713-0. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ Richard Sylla, Gianni Toniolo. (2002). Patterns of European Industrialisation: The Nineteenth Century. pg. 230. Conversion from 1970 to 2010 dollars here

- ↑ Israel Bartal; Antony Polonsky (1999). Focusing on Galicia: Jews, Poles, and Ukrainians, 1772-1918. Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-874774-40-2. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

Galician poverty became proverbial in the second half of the nineteenth century

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Schatzker, Valerie; Erdheim, Claudia; Sharontitle, Alexander. "Petroleum in Galicia". Drohobycz Administrative District: History. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Golonka, Jan; Picha, Frank J. (2006). The Carpathians and Their Foreland: Geology and Hydrocarbon Resources. American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG). ISBN 9780891813651.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Creswell, Sarah; Flint, Tom. "William H. McGarvey (1843 - 1914)". Professional Engineers Ontario. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frank, Allison (June 29, 2006). "Galician California, Galician Hell: The Peril and Promise of Oil Production in Austria-Hungary". Washington, D.C.: Office of Science and Technology Austria (OSTA). Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ↑ Thompson, Arthur Beeby (1916). Oil-field Development and Petroleum Mining. Van Nostrand.

- ↑ Schwarz, Robert (1930). Petroleum-Vademecum: International Petroleum Tables (VII ed.). Berlin and Vienna: Verlag für Fachliteratur. pp. 4–5.

Sources

- Berend, Nora (2006). At the Gate of Christendom: Jews, Muslims and "Pagans" in Medieval Hungary, c. 1000-c.1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02720-5.

- Buttar, Prit (2016). Collision of Empires: The War on the Eastern Front in 1914. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781782006480.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

Further reading

- Dohrn, Verena. Journey to Galicia, (S. Fischer, 1991), ISBN 3-10-015310-3

- Frank, Alison Fleig. Oil Empire: Visions of Prosperity in Austrian Galicia (Harvard University Press, 2005). A new monograph on the history of the Galician oil industry in both the Austrian and European contexts.

- Christopher Hann and Paul Robert Magocsi, eds., Galicia: A Multicultured Land (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005). A collection of articles by John Paul Himka, Yaroslav Hrytsak, Stanislaw Stepien, and others.

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Galicia: A Historical Survey and Bibliographic Guide (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1983). Concentrates on the historical, or Eastern Galicia.

- Andrei S. Markovits and Frank E. Sysyn, eds., Nationbuilding and the Politics of Nationalism: Essays on Austrian Galicia (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1982). Contains an important article by Piotr Wandycz on the Poles, and an equally important article by Ivan L. Rudnytsky on the Ukrainians.

- A.J.P. Taylor, The Habsburg Monarchy 1809–1918, 1941, discusses Habsburg policy toward ethnic minorities.

- Wolff, Larry. The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture (Stanford University Press; 2010) 504 pages. Examines the role in history and cultural imagination of a province created by the 1772 partition of Poland that later disappeared, in official terms, in 1918.

- (Polish) Grzegorz Hryciuk, Liczba i skład etniczny ludności tzw. Galicji Wschodniej w latach 1931–1959, [Number and Ethnic Composition of the People of so-called Eastern Galicia 1931–1959] Lublin 1996

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Galicia (Central Europe). |

| Timeline of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Territory (major city) |

Zamosch area | New Galicia (Lublin) |

Krakau area | Neu Sandez area | Galicia (Lemberg) |

Tarnopol area | Bukovina (Czernowitz) | ||||||

| Years | western | eastern | |||||||||||

| before 1769 | part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth | part of Moldavia | |||||||||||

| 1769–1772 | to Austria, ca. 1769 | ||||||||||||

| 1772–1775 | First Partition of Poland, 1772 | First Partition of Poland, 1772 | |||||||||||

| 1775–1789 | Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria including the duchies of Auschwitz and Zator; part of the Habsburg Empire, 1772–1804; of the Austrian Empire, 1804–1867; of Cisleithania, Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918 |

Bukovina Military District, 1775–1789 | |||||||||||

| 1789–1795 | Bukovina District, 1789–1849 | ||||||||||||

| 1795–1803 | Third Partition of Poland, 1795 New Galicia (or West Galicia) | ||||||||||||

| 1803–1809 | New Galicia merged into Galicia, 1803 | ||||||||||||

| 1809–1815 | to the Duchy of Warsaw, 1809–1815 | to Russia, 1809–1815 | |||||||||||

| 1815–1846 | to the "Congress" Kingdom of Poland, 1815–1918 | Free City of Kraków, 1815–1846 | |||||||||||

| 1846–1849 | Grand Duchy of Cracow, 1846–1918 | ||||||||||||

| 1849–1918 | Duchy of Bukovina, 1849–1918 | ||||||||||||

| 1918–1919 | to Poland, 1918 | West Ukrainian People's Republic, 1918–1919 | to Romania, 1918 | ||||||||||

| after 1919 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Coordinates: 49°49′48″N 24°00′51″E / 49.8300°N 24.0142°E