Polish United Workers' Party

Polish United Workers' Party Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza | |

|---|---|

| |

| First leader | Bolesław Bierut |

| Last leader | Mieczysław Rakowski |

| Founded | 16–21 December 1948 |

| Dissolved | 27–30 January 1990 |

| Merger of | Polish Socialist Party and Polish Workers' Party |

| Headquarters |

Nowy Świat 6/12, 00-497 Warsaw |

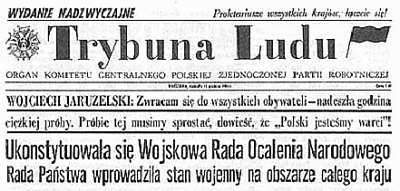

| Newspaper | Trybuna Ludu |

| Youth wing | Polish Socialist Youth Union |

| Membership (1970s) | 3,500,000 |

| Ideology |

Communism Marxism–Leninism |

| International affiliation | Cominform |

| Colors | Red |

| Anthem | "The Internationale" |

The Polish United Workers' Party (PUWP; Polish: Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR) was the Communist party which governed the People's Republic of Poland from 1948 to 1989. Ideologically it was based on the theories of Marxism-Leninism.[1]

Program and goals

Until 1989, the PUWP held dictatorial powers (the amendment to the constitution of 1976 mentioned "a leading national force"), and controlled an unwieldy bureaucracy, the military, the secret police, and the economy. Its main goal was to create a Communist society and help to propagate Communism all over the world. On paper, the party was organised on the basis of democratic centralism, which assumed a democratic appointment of authorities, making decisions, and managing its activity. Yet in fact, the key roles were played by the Central Committee, its Politburo and Secretariat, which were subject to the strict control of the authorities of the Soviet Union. These authorities decided about the policy and composition of the main organs; although, according to the statute, it was a responsibility of the members of the congress, which was held every five or six years. Between sessions, party conferences of the regional, county, district and work committees were taking place. The smallest organizational unit of the PUWP was the Fundamental Party Organization (FPO), which functioned in work places, schools, cultural institutions, etc.

The main part in the PUWP was played by professional politicians, or the so-called "party's hard core", formed by people who were recommended to manage the main state institutions, social organizations, and trade unions. In the crowning time of the PUWP's development (the end of the 1970s) it consisted of over 3.5 million members. The Political Office of the Central Committee, Secretariat and regional committees appointed the key posts not only within the party, but also in all organizations having ‘state’ in its name – from central offices to even small state and cooperative companies. It was called the nomenklatura system of the state and economy management. In certain areas of the economy, e.g., in agriculture, the nomenklatura system was controlled with an approval of the PUWP and by its allied parties, the United People's Party (agriculture and food production), and the Democratic Party (trade community, small enterprise, some cooperatives). After martial law began, the Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth was founded to organize these and other parties.

History

Establishment and Sovietisation period

The Polish United Workers' Party was established at the unification congress of the Communist Polish Workers' Party (PPR) and Polish Socialist Party (PPS) during meetings held from 15 to 21 December 1948. The unification was possible because the PPS activists who opposed unification (or rather absorption by Communists) had been forced out of the party. Similarly, the members of the PPR who were accused of "rightist – nationalistic deviation" were expelled. Thus, for all intents and purposes, the PUWP was the PPR under a new name.

"Rightist-nationalist deviation" (Polish: odchylenie prawicowo-nacjonalistyczne) was a political propaganda term used by the Polish Stalinists against prominent activists, such as Władysław Gomułka and Marian Spychalski who opposed Soviet involvement in the Polish interior affairs, as well as internationalism displayed by the creation of the Cominform and the subsequent merger that created the PZPR. It is believed that it was Joseph Stalin who put pressure on Bolesław Bierut and Jakub Berman to remove Gomułka and Spychalski as well as their followers from power in 1948. It is estimated that over 25% of socialists were removed from power or expelled from political life.

Bolesław Bierut, an NKVD agent,[2] and a hard Stalinist served as first Secretary General of the ruling PUWP from 1948 to 1956, playing a leading role in the Sovietisation of Poland and the installation of her most repressive regime. He had served as President since 1944 (though on a provisional basis until 1947). After a new constitution abolished the presidency, Bierut took over as Prime Minister. until his death in 1956.

Bierut oversaw the trials of many Polish wartime military leaders, such as General Stanisław Tatar and Brig. General Emil August Fieldorf, as well as 40 members of the Wolność i Niezawisłość (Freedom and Independence) organisation, various Church officials and many other opponents of the new regime including the "hero of Auschwitz", Witold Pilecki, condemned to death during secret trials. Bierut signed many of those death sentences.

Bierut's death in Moscow in 1956 (shortly after attending the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union) gave rise to much speculation about poisoning or a suicide, and symbolically marked the end of the era of Stalinism in Poland.

Gomułka's autarchic communism

In 1956, shortly after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the PUWP leadership split in two factions, dubbed Natolinians and Puławians. The Natolin faction - named after the place where its meetings took place, in a government villa in Natolin - were against the post-Stalinist liberalization programs (Gomułka thaw) and they proclaimed simple nationalist and antisemitic slogans as part of a strategy to gain power. The most well known members included Franciszek Jóźwiak, Wiktor Kłosiewicz, Zenon Nowak, Aleksander Zawadzki, Władysław Dworakowski, Hilary Chełchowski.

The Puławian faction - the name comes from the Puławska Street in Warsaw, on which many of the members lived - sought great liberalization of socialism in Poland. After the events of Poznań June, they successfully backed the candidature of Władysław Gomułka for First Secretary of party, thus imposing a major setback upon Natolinians. Among the most prominent members were Roman Zambrowski and Leon Kasman. Both factions disappeared towards the end of the 1950s.

Initially very popular for his reforms and seeking a "Polish way to socialism",[3] and beginning an era known as Gomułka's thaw, he came under Soviet pressure. In the 1960s he supported persecution of the Roman Catholic Church and intellectuals (notably Leszek Kołakowski who was forced into exile). He participated in the Warsaw Pact intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968. At that time he was also responsible for persecuting students as well as toughening censorship of the media. In 1968 he incited an anti-Zionist propaganda campaign, as a result of Soviet bloc opposition to the Six-Day War.

In December 1970, a bloody clash with shipyard workers in which several dozen workers were fatally shot forced his resignation (officially for health reasons; he had in fact suffered a stroke). A dynamic younger man, Edward Gierek, took over the Party leadership and tensions eased.

Gierek's economic opening

In the late 1960s, Edward Gierek had created a personal power base and become the recognized leader of the young technocrat faction of the party. When rioting over economic conditions broke out in late 1970, Gierek replaced Władysław Gomułka as party first secretary.[4] Gierek promised economic reform and instituted a program to modernize industry and increase the availability of consumer goods, doing so mostly through foreign loans.[5] His good relations with Western politicians, especially France's Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and West Germany's Helmut Schmidt, were a catalyst for his receiving western aid and loans.

The standard of living increased markedly in the Poland of the 1970s, and for a time he was hailed a miracle-worker. The economy, however, began to falter during the 1973 oil crisis, and by 1976 price increases became necessary. New riots broke out in June 1976, and although they were forcibly suppressed, the planned price increases were canceled.[6] High foreign debts, food shortages, and an outmoded industrial base compelled a new round of economic reforms in 1980. Once again, price increases set off protests across the country, especially in the Gdańsk and Szczecin shipyards. Gierek was forced to grant legal status to Solidarity and to concede the right to strike. (Gdańsk Agreement).

Shortly thereafter, in early September 1980, Gierek was replaced as by Stanisław Kania as General Secretary of the party by the Central Committee, amidst much social and economic unrest. Kania admitted that the party had made many economic mistakes, and advocated working with Catholic and trade unionist opposition groups. He met with Solidarity Union leader Lech Wałęsa, and other critics of the party. Though Kania agreed with his predecessors that the Communist Party must maintain control of Poland, he never assured the Soviets that Poland would not pursue actions independent of the Soviet Union. On October 18, 1981, the Central Committee of the Party withdrew confidence on him, and Kania was replaced by Prime Minister (and Minister of Defence) Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski.

Jaruzelski's autocratic rule

On 11 February 1981, Jaruzelski was elected Prime Minister of Poland and became the first secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party on October 18 the same year. Before initiating the plan, he presented it to Soviet Premier Nikolai Tikhonov. On 13 December 1981, Jaruzelski imposed martial law in Poland

In 1982 Jaruzelski revitalized the Front of National Unity, the organization the Communists used to manage their satellite parties, as the Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth.

In 1985, Jaruzelski resigned as prime minister and defence minister and became chairman of the Polish Council of State, a post equivalent to that of president or a dictator, with his power centered on and firmly entrenched in his coterie of "LWP" generals and lower ranks officers of the Polish People's Army.

Breakdown of autocracy

The attempt to impose a naked military dictatorship, notwithstanding, the policies of Mikhail Gorbachev stimulated political reform in Poland. By the close of the tenth plenary session in December 1988, the Polish United Workers Party was forced, after strikes, to approach leaders of Solidarity for talks.

From 6 February to 15 April 1989, negotiations were held between 13 working groups during 94 sessions of the roundtable talks.

These negotiations resulted in an agreement which stated that a great degree of political power would be given to a newly created bicameral legislature. It also created a new post of president to act as head of state and chief executive. Solidarity was also declared a legal organization. During the following Polish elections the Communists won 65 percent of the seats in the Sejm, though the seats won were guaranteed and the Communists were unable to gain a majority, while 99 out of the 100 seats in the Senate freely contested were won by Solidarity-backed candidates. Jaruzelski won the presidential ballot by one vote.

Jaruzelski was unsuccessful in convincing Wałęsa to include Solidarity in a "grand coalition" with the Communists, and resigned his position of general secretary of the Polish United Workers Party. The PZPR' two allied parties broke their long-standing alliance, forcing Jaruzelski to appoint Solidarity's Tadeusz Mazowiecki as the country's first non-Stalinist prime minister since 1948. Jaruzelski resigned as Poland's President in 1990, being succeeded by Wałęsa in December.

Dissolution of the PUWP

Starting from January 1990, the collapse of the PUWP became inevitable. All over the country, public occupations of the party buildings started in order to prevent stealing the party's possessions and destroying or taking the archives. On 29 January 1990, XI Congress was held, which was supposed to recreate the party. Finally, the PUWP dissolved, and some of its members decided to establish two new social-democratic parties. They get over $1 million from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union known as the Moscow loan.

The former activists of the PUWP established the Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland (in Polish: Socjaldemokracja Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej, SdRP), of which the main organizers were Leszek Miller and Mieczysław Rakowski. The SdRP was supposed (among other things) to take over all rights and duties of the PUWP, and help to divide out the property of the former PUWP. Up to the end of the 1980s, it had considerable incomes mainly from managed properties and from the RSW company ‘Press- Book-Traffic’, which in turn had special tax concessions. During this period, the income from membership fees constituted only 30% of the PUWP's revenues. After the dissolution of the PUWP and the establishment of the SdRP, the rest of the activists formed the Social Democratic Union of the Republic of Poland (USdRP), which changed its name to the Polish Social Democratic Union, and The 8th July Movement.

At the end of 1990, there was an intense debate in the Sejm on the takeover of the wealth that belonged to the former PUWP. Over 3000 buildings and premises were included in the wealth and almost half of it was used without legal basis. Supporters of the acquisition argued that the wealth was built on the basis of plunder and the Treasury grant collected by the whole society. Opponents of SdRP claimed that the wealth was created from membership fees; therefore, they demanded wealth inheritance for SdPR which at that time administered the wealth. Personal property and the accounts of the former PUWP were not subject to control of a parliamentary committee.

On 9 November 1990, the Sejm passed "The resolution about the acquisition of the wealth that belonged to the former PUWP". This resolution was supposed to result in a final takeover of the PUWP real estate by the Treasury. As a result, only a part of the real estate was taken over mainly for a local government by 1992, whereas a legal dispute over the other party carried on till 2000. Personal property and finances of the former PUWP practically disappeared. According to the declaration of SdRP Members of Parliament, 90-95% of the party's wealth was allocated for gratuity or was donated for a social assistance.

Building

The Central Committee had its seat in the Party's House, a building erected by obligatory subscription from 1948 to 1952 and colloquially called White House or the House of Sheep. Since 1991 the Bank-Financial Center "New World" is located in this building. From 1991-2000 the Warsaw Stock Exchange also had its seat there.

Party leaders

By the year 1954 the head of the party was the Chair of Central Committee:

| # | Name | Picture | Took office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bolesław Bierut (1892–1956) | .jpg) | December 22, 1948 | March 12, 1956 | General Secretary |

| 2 | Edward Ochab (1906–1989) | .jpg) | March 20, 1956 | October 21, 1956 | First Secretary |

| 3 | Władysław Gomułka (1905–1982) |  | October 21, 1956 | December 20, 1970 | First Secretary |

| 4 | Edward Gierek (1913–2001) |  | December 20, 1970 | September 6, 1980 | First Secretary |

| 5 | Stanisław Kania (1927– ) |  | September 6, 1980 | October 18, 1981 | First Secretary |

| 6 | Wojciech Jaruzelski (1923–2014) |  | October 18, 1981 | July 29, 1989 | First Secretary |

| 7 | Mieczysław Rakowski (1926–2008) |  | July 29, 1989 | January 29, 1990 | First Secretary |

Leading figures of the PUWP

|

|

|

Notable politicians after 1989

Presidents

Prime ministers

European Commissioners

See also

- Politburo of the Polish United Workers' Party

- List of Polish United Workers' Party members

- Eastern Bloc politics

- Communist Party of Poland (1918 - 1938 y.)

- Polish Communist Party (2002) - receiver with 2002 year

Notes

- 1 2 Hubert Zawadzki, Jerzy Lukowski, A Concise History of Poland, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-521-85332-X, Google Print, p.295-296

- ↑ Błażyński, Zbigniew (2003). Mówi Józef Światło. Za kulisami bezpieki i partii, 1940-1955. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo LTW. pp. 20/21, 27. ISBN 83-88736-34-5.

- ↑ "Rebellious Compromiser". Time Magazine. 10 December 1956. Retrieved 2006-10-14.

- ↑ Time magazine article from Jan. 4, 1971, The World: Poland's New Regime: Gifts and Promises

- ↑ Time magazine article from Oct. 14, 1974, POLAND: Gierek: Building from Scratch

- ↑ Time magazine article from Nov. 8, 1976 POLAND: The Winter of Discontent

External links

- MSWiA - Sprawozdanie z likwidacji majątku byłej PZPR (MSWiA - The report on the liquidation of property of the former PZPR) (Polish)