Priene

|

Πριήνη (Ancient Greek) Prien (Turkish) | |

The Temple of Athena, funded by Alexander the Great, at the foot of an escarpment of Mycale. The five columns were erected in 1965–66 from rubble and are 3 metres (9.8 ft) short of the calculated original column height. | |

Shown within Turkey | |

| Alternate name | Sampson |

|---|---|

| Location | Güllübahçe Turun, Aydın Province, Turkey |

| Region | Ionia |

| Coordinates | 37°39′35″N 27°17′52″E / 37.65972°N 27.29778°ECoordinates: 37°39′35″N 27°17′52″E / 37.65972°N 27.29778°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 37 ha (91 acres) |

| History | |

| Builder | Theban colonists |

| Founded | Approximately 1000 BCE |

| Associated with | Bias, Pythius |

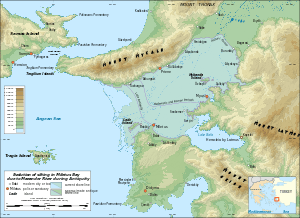

Priene (Ancient Greek: Πριήνη Priēnē; Turkish: Prien) was an ancient Greek city of Ionia (and member of the Ionian League) at the base of an escarpment of Mycale, about 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) north of the then course of the Maeander (now called the Büyük Menderes or "Big Maeander") River, 67 kilometres (42 mi) from ancient Anthea, 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) from ancient Aneon and 25 kilometres (16 mi) from ancient Miletus. It was formerly on the sea coast, built overlooking the ocean on steep slopes and terraces extending from sea level to a height of 380 metres (1,250 ft) above sea level at the top of the escarpment.[1] Today, after several centuries of changes in the landscape, it is an inland site. It is located at a short distance west of the modern village Güllübahçe Turun in the Söke district of Aydın Province, Turkey

Priene possessed a great deal of famous Hellenistic art and architecture. The city's original position on Mount Mycale has never actually been discovered; however, it is believed that it was a peninsula possessing two harbours. Priene never held a great deal of political importance due to the city's size, as it is believed around 4 to 5 thousand inhabitants occupied the region. The city was arranged into four districts, firstly the political district which consisted of the bouleuterion and the prytaneion, the cultural district containing the theatre, the commercial where the agora was located and finally the religious district which contained sanctuaries dedicated to Zeus and Demeter and most importantly the Temple of Athena.

Historical geography

Earliest cities

The city visible on the slopes and escarpment of Mycale was constructed according to plan entirely within the 4th century BCE. It was not the original Priene, which had been a port city situated at the then mouth of the Maeander River. This location caused insuperable environmental difficulties for it due to slow aggradation of the riverbed and progradation in the direction of the Aegean Sea. Typically the harbour would silt over and the population find itself living in pest-ridden swamps and marshes. The underlying causes of the problem are that the Maeander flows through a slowly subsiding rift valley creating a drowned coastline and that human use of the previously forested slopes and valley denudes the countryside and accelerates erosion. The sediments are progressively deposited in the trough at the mouth of the river, which migrates westward and more than compensates for the subsidence.

Physical remains of the original Priene have not yet been identified, because, it is supposed, they must be under many feet of sediment, the top of which is currently valuable agricultural land. Knowledge of the average rate of progradation is the basis for estimating the location of the city, which was moved every few centuries to renew its utility as a port. The Greek city (there may have been unknown habitations of other ethnicities, as at Miletus) was founded by a colony from the ancient Greek city of Thebes in the vicinity of ancient Aneon at about 1000 BCE. At about 700 BCE a series of earthquakes provided the opportunity for a move to within 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) of its 4th century BCE location. At about 500 BCE the city moved again to a few km away at the port of Naulochos.[2]

4th century BCE city

.jpg)

The leading citizens were quick to follow suit: most of the public buildings were constructed at private expense and are inscribed with the names of the donors.

The ruins of the city are generally conceded to be the most spectacular surviving example of an entire ancient Greek city intact except for the ravages of time. It has been studied since at least the 18th century and still is. The city was constructed of marble from nearby quarries on Mycale and wood for such items as roofs and floors. The public area is laid out in a grid pattern up the steep slopes, drained by a system of channels. The water distribution and sewer systems survive. Foundations, paved streets, stairways, partial door frames, monuments, walls, terraces can be seen everywhere among toppled columns and blocks. No wood has survived. The city extends upward to the base of an escarpment projecting from Mycale. A narrow path leads to the acropolis above.

Later years

Despite the expectations of the population Priene lasted only a few more centuries as a deep-water port. In the 2nd century CE Pausanias reports that the Maeander already had silted over the inlet in which Myus stood and that the population had abandoned it for Miletus.[4] While Miletus was apparently still open then, according to recent geoarchaeological research Priene had already lost the port and open connection to the sea in about the 1st century BCE.[5] Very likely, its merchants had preceded the people of Myus to Miletus. By 300 CE the entire Bay of Miletus, except for Lake Bafa, was silted in.

Today Miletus is many miles from the sea and Priene stands at the edge of a fertile plain, now a checkerboard of privately owned fields. A Greek village remained after the population decline and was joined by a Turkish population after the 12th century CE. In the 13th century CE Priene was known as Sampson in Greek after the biblical hero Samson (Samsun Kale, "Samson's Castle" in Turkish). In 1204, Sabas Asidenos, a local magnate, established himself as the city's ruler, but soon had to recognize the rule of the Empire of Nicaea. The area remained under Byzantine control until the late 13th century.

By 1923 whatever Greek population remained was expelled in the population exchange between Greece and Turkey and shortly after the Turkish population moved to a more favourable location, which they called Güllü Bahçe, "rose garden", the old Greek settlement partly still in use, today with the name Gelebeç or Kelebeş. The tourist attraction of Priene is accessible from there.

Contemporary geography

Territory

In the 4th century BCE Priene was a deep-water port with two harbours overlooking the Bay of Miletus[6] and somewhat further east the marshes of the Maeander Delta. Between the ocean and steep Mycale agricultural resources were limited although Priene's territory probably did include a part of the Maeander Valley. Claiming much of Mycale it had borders on the north with Ephesus and Thebes, a small state on Mycale.

Priene was a small city-state of only 6000 persons living in a constrained space of only 15 hectares (37 acres). The walled area had an extent of 20 hectares (49 acres) to 37 hectares (91 acres). The population density of its residential district has been estimated at 166 persons per hectare living in about 33 homes per hectare (13 per acre) arranged in compact city blocks.[7] The entire space within the walls offered not much more space and privacy: the density was 108 persons per hectare. All the public buildings were within walking distance, except that walking must have been an athletic event due to the vertical components of the distances.

Society

Priene was a wealthy city, as the plenitude of fine urban homes in marble and the private dedications of public buildings suggests, not to mention the personal attentions of Mausolus and Alexander the Great. One third of them had indoor toilets, a rarity in a society typically featuring public banks of outdoor seats in urban environments, side by side, an arrangement for which the flowing robes of the ancients were suitably functional. Indoor plumbing requires more extensive water supply and sewage systems. Priene's location was appropriate in that regard; they captured springs and streams on Mycale, brought them in by aqueduct to cisterns and piped or channeled from there to houses and fountains. Most Greek cities, such as Athens, required visits to the public fountains (the work of domestic servants), but the upper third of Prieneian society had access to indoor water.

The source of Ionian wealth was maritime activity; Ionia had a reputation among the other Greeks for being luxurious, against which practices the intellectuals, such as Heraclitus often railed.

Government

Although the stereotyped equation of wealth with aristocracy may have applied early in Priene's history, in the 4th century BCE it was a democracy. State authority resided in a body called the Πριηνείς (Priēneis), "the Prieneian people", who issued all decrees and other public documents in their name. The coins minted at Priene featured the helmeted head of Athena on the obverse and a meander pattern on the reverse, one coin also displaying a dolphin and the legend ΠΡΙΗ for ΠΡΙΗΝΕΩΝ (Priēneōn), "of the Prieneians."[8] These symbols express a self-view of the Prieneians as a maritime democracy aligned with Athens but located in Asia.

The mechanism of democracy was similar to but simpler than that of the Athenians (who had a many times greater population). An assembly of citizens met periodically to render major decisions placed before them. The day-to-day legislative and executive business was conducted by a boulē, or city council, which met in a bouleuterion like a small theatre with a wooden roof. The official head of state was a prytane. He and more specialized magistrates were elected periodically. And yet, as at Athens, not all the population was franchised. For example, the property rights and tax responsibilities of a non-Prieneian section of the population living in the countryside, the pedieis, "plainsmen", were defined by law. They were perhaps, an inheritance from the days when Priene was in the valley.

History

Although the exact truth is not known, Priene was said to have been first settled by Ionians under Aegyptus, a son of Belus and grandson of King Codrus, in the 11th century BCE. After successive attacks by Cimmerians, Lydians under Ardys II, and Persians, it survived and prospered under the direction of its "sage," Bias, during the middle of the 6th century BC.[1] Cyrus captured it in 545 BC; but it was able to send twelve ships to join the Ionic Revolt (499 BC-494 BC).

Priene was a member of the Athenian dominated Delian League in the 5th century BC and in 387 BC came under Persian dominance again until Alexander the Great's conquest.[9] Disputes with Samos, and the troubles after Alexander's death, brought Priene low, and Rome had to save it from the kings of Pergamon and Cappadocia in 155.

Orophernes, the rebellious brother of the Cappadocian king, who had deposited a treasure there and recovered it by Roman intervention, restored the temple of Athena as a thank-offering. Under Roman and Byzantine dominion Priene had a prosperous history. It passed into Muslim hands late in the 13th century.[10]

Archaeological excavations and current state

The ruins, which lie in successive terraces, were the object of missions sent out by the English Society of Dilettanti in 1765 and 1868, and were thoroughly laid open by Theodor Wiegand (1895–1899) for the Berlin Museum. The city, as refounded at a new site in the 4th century, was laid out on a rectangular scheme. The steep area faces south, the acropolis rising nearly 200 metres (660 ft) behind it. The city was enclosed by a wall 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) thick with towers at intervals and three principal gates.

On the lower slopes of the acropolis was a sanctuary of Demeter. The town had six main streets, about 6 metres (20 ft) wide, running east and west and fifteen streets about 3 metres (9.8 ft) wide crossing at right angles, all being evenly spaced; and it was thus divided into about 80 insulae. Private houses were apportioned eight to an insula. The systems of water-supply and drainage can easily be discerned. The houses present many analogies with the earliest Pompeian. In the western half of the city, on a high terrace north of the main street and approached by a fine stairway, was the temple of Athena Polias, a hexastyle peripteral structure in the ionic order built by Pytheos, the architect of the Mausoleum of Maussollos at Halikarnassos, one of the seven wonders. Under the basis of the statue of Athena were found in 1870 silver tetradrachms of Orophernes, and some jewellery, probably deposited at the time of the Cappadocian restoration.

An ancient Priene Synagogue with a carved image of a menorah has also been discovered.[11]

Around the agora, the main square crossed by the main street, is a series of halls. The municipal buildings, buleuterion and prytaneion lie north of the Agora, further in the north the Upper Gymnasium with Roman baths, and the well preserved Hellenistic theatre but all, like all the other public structures, more or less in the centre of the plan. Temples of Asclepius and the Egyptian Gods Isis, Serapis and Anubis have been laid bare. At the lowest point on the south, within the walls, was the large stadium, connected with a gymnasium of Hellenistic times.[12]

See also

- Society of Dilettanti, Ionian Antiquities (1821), vol. ii.;

- Th. Wiegand and H. Schrader, Priene (1904);

- on inscriptions (360) see Hiller von Gaertringen, Inschriften von Priene (Berlin, 1907), with collection of ancient references to the city

Notes

- 1 2 Grant, Michael (1986). A Guide to the Ancient World. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. pp. 523–524. ISBN 0-7607-4134-4.

- ↑ Crouch (2004) pages 199-200.

- ↑ British Museum Highlights

- ↑ Description of Greece Book 7 Section 2.11.

- ↑ Marc Müllenhoff Geoarchäologische, sedimentologische und morphodynamische Untersuchungen im Mündungsgebiet des Büyük Menderes (Mäander), Westtürkei Marburg/Lahn 2005

- ↑ This article uses this term in preference to the Gulf of Latmus, which remains as Lake Bafa. In ancient times they were continuous.

- ↑ Hansen (2004), pages 14–16, estimates the walled area as 1.33 to 2 times a measured habitation area of 15 hectares (37 acres). Rubinstein (2004), pages 1091–1093, gives a slightly larger measure of the walled area: 37 hectares (91 acres). Hansen (2004), pages 14–16, estimates 8 persons per house for 500 counted houses and a ratio of 2:1 of urban over rural.

- ↑ Rubinstein (2004), pages 1091–1093.

- ↑

Pétridès, Sophron (1913). "Priene". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Pétridès, Sophron (1913). "Priene". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Priene". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Priene". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Letter from the Field: An Ancient Synagogue Comes to Light, Mark Wilson, Biblical Archaeology Review,

- ↑ Rumscheid, Frank (1998). Priene: A Guide to the Pompeii of Asia Minor. Turkey: Ege Yayınları. ISBN 975-8070-16-9.

References

- Crouch, Dora P. (2004). Geology and Settlement: Greco-Roman Patterns. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508324-5.

- Hansen, Mogens Herman (2004). Nielsen, Thomas Heine, ed. "Once again: Studies in the Ancient Greek Polis: Papers from the Copenhagen Polis Centre 7". Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 3-515-08438-X.

|contribution=ignored (help) - Rubinstein, Lene (2004). Hansen, Mogens Herman; Nielsen, Thomas Heine, eds. "An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis: An Investigation Conducted by the Danish National Research Foundation". Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814099-1.

|contribution=ignored (help)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Priene. |

- Livius Picture Archive: Priene

- Priene and Miletus İnformation

- Priene Miletus and Didyma images

- Many pictures of the ancient city of Priene

- The Theatre at Priene, The Ancient Theatre Archive. Theatre specifications and virtual reality tour of theatre

- Herodotus Project: Extensive B+W photo essay of Priene

- Priene information guide and photos

- Hellenistic inscriptions of Priene, in English translation

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Priene". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Priene". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.