Primer (film)

| Primer | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Shane Carruth |

| Produced by | Shane Carruth |

| Written by | Shane Carruth |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Shane Carruth |

| Edited by | Shane Carruth |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 77 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7,000[2] |

| Box office | $424,760[3] |

Primer is a 2004 American independent science fiction drama film about the accidental discovery of time travel. The film was written, directed, produced, edited and scored by Shane Carruth, who also stars in the main role.

Primer is of note for its extremely low budget, experimental plot structure, philosophical implications, and complex technical dialogue, which Carruth, a college graduate with a degree in mathematics and a former engineer, chose not to simplify for the sake of the audience.[4] The film collected the Grand Jury Prize at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival, before securing a limited release in the United States, and has since gained a cult following.[5]

Plot

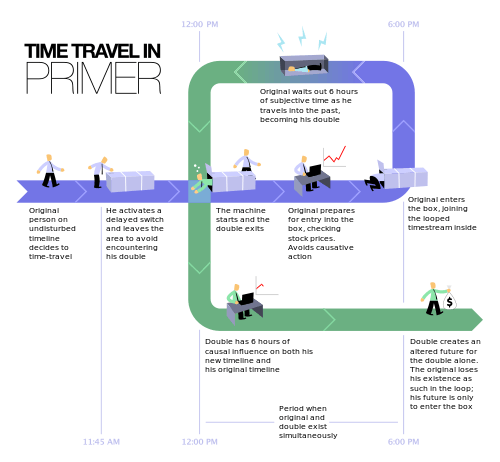

Two engineers – Aaron and Abe – supplement their day-jobs with entrepreneurial tech projects, working out of Aaron's garage. During one such research effort, involving electromagnetic reduction of objects' weight, the two men accidentally discover an 'A-to-B' time loop side-effect; objects left in the weight-reducing field exhibit temporal anomalies, proceeding normally (from time 'A,' when the field was activated, to time 'B,' when the field is powered off), then backwards (from 'B' back to 'A'), in continuous A-then-B-then-A-then-B sequence, such that objects can leave the field in the present, or at some previous point.

Abe refines this proof-of-concept and builds a stable time-apparatus ("the box"), sized to accommodate a human subject. Abe uses this "box" to travel six hours into his own past—as part of this process, Original-Abe sits incommunicado in a hotel room, so as not to interact or interfere with the outside world, after which Original-Abe enters the "box," waits inside the "box" for six hours (thus going back in time six hours), and becomes Future-Overlap-Double-Abe, who travels across town, explains the proceedings to Aaron, and brings Aaron back to the secure self-storage facility housing the "box." At the end of the overlap-timespan, Original-Abe no longer exists, having entered the "box," rewound six hours, and become Future-Overlap-Double-Abe for the remainder of time.

Abe and Aaron repeat Abe's six-hour experiment multiple times over multiple days, making profitable same-day stock trades armed with foreknowledge of the market's performance. The duo's divergent personalities – Abe cautious and controlling, Aaron impulsive and meddlesome – put subtle strain on their collaboration and friendship. These tensions come to a head after a late-night encounter with Thomas Granger (father to Abe's girlfriend Rachel), who appears inexplicably unshaven and exists in overlap with his original suburban self. Granger falls into a comatose state after being pursued by Aaron; Aaron theorizes that, at some point in the future, Granger entered the "box" (at an unknown time, for unknown reasons), with timeline-altering consequences. Abe concludes that time travel is simply too dangerous, and uses a second apparatus (his "failsafe box," built before the experiment's beginning and kept continuously running in a secret location), traveling back four days to prevent the experiment's launch.

Cumulative competing interference wreaks havoc upon the timeline. Future-Abe sedates Original-Abe (so he will never conduct the initial time travel experiment), and meets Original-Aaron at a park bench (so as to dissuade him), but finds that Future-Aaron has gotten there first (armed with pre-recordings of the past conversations, and an unobtrusive earpiece), having brought a disassembled "third failsafe box" four days back with his own body. Future-Abe faints at this revelation, overcome by shock and fatigue.

The two men briefly and tentatively reconcile. They jointly travel back in time, experiencing and reshaping an event where Abe's girlfriend Rachel was nearly killed by a gun-wielding party crasher. After many repetitions, Aaron, forearmed with knowledge of the party's events, stops the gunman, becoming a local hero. Abe and Aaron ultimately part ways; Aaron considers a new life in foreign countries where he can tamper more broadly for personal gain, while Abe states his intent to remain in town and dissuade/sabotage the original "box" experiment. Abe warns Aaron to leave and never return.

An epilogue sequence reveals that multiple "box-aware" versions of Aaron are still alive and circulating – at least one Future-Aaron has intermingled knowledge with Original-Aaron (thanks to discussions, voice-recordings, and an unsuccessful physical altercation). As a result, two or more Aarons now inhabit the same timeline, sharing information of future events, in stark contrast to Abe, who goes to painstaking extremes to keep his Original-Abe "pure" and unaware of the future. The film's final scene depicts a fully aware Aaron, directing French-speaking workers in the construction of what appears to be a warehouse-sized "box."

Cast

- Shane Carruth as Aaron

- David Sullivan as Abe

- Casey Gooden as Robert

- Anand Upadhyaya as Phillip

- Carrie Crawford as Kara

- Samantha Thomson as Rachel Granger

- Brandon Blagg as Will

Carruth cast himself as Aaron after having trouble finding actors who could "break ... the habit of filling each line with so much drama".[4] Most of the other actors are either friends or family members.[6][7]

Themes

Although one of the more fantastic elements of science fiction is central to the film, Carruth's goal was to portray scientific discovery in a down-to-earth and realistic manner. He notes that many of the greatest breakthrough scientific discoveries in history have occurred by accident, in locations no more glamorous than Aaron's garage.[8]

Whether it involved the history of the number zero or the invention of the transistor, two things stood out to me. First is that the discovery that turns out to be the most valuable is usually dismissed as a side-effect. Second is that prototypes almost never include neon lights and chrome. I wanted to see a story play out that was more in line with the way real innovation takes place than I had seen on film before.[8]

Carruth has said he intended the central theme of the film to be the breakdown of Abe and Aaron's relationship,[9] as a result of their inability to cope with the power afforded them by this technological advancement:

First thing, I saw these guys as scientifically accomplished but ethically, morons. They never had any reasons before to have ethical questions. So when they're hit with this device they're blindsided by it. The first thing they do is make money with it. They're not talking about the ethics of altering your former self.[2]

Physics and science

- Aaron and Abe start the film by attempting to create a device to somehow counter the effects of gravity. They have plans for such a device from another development team, but wish to improve on the viability of the design. Their main approach to achieve this is to discard the coolant bath for the required superconductors. They instead increase the transition temperature of the superconductor to "something more usable". The time machine makes use of the property of superconductors called the Meissner effect, which "knock[s] out the interior magnetic field".

- Aaron and Abe require palladium to build their machine. This is the reason they take the catalytic converter containing a small amount of palladium from a car.

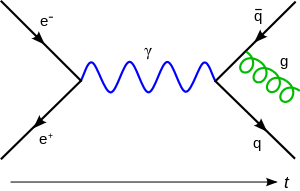

- The principles of time travel in the film are inspired by Feynman diagrams. Carruth explained: "Richard Feynman has some interesting ideas about time. When you look at Feynman diagrams [which map the interaction of elementary particles], there's really no difference between watching an interaction happen forward and backward in time."[10]

Production

While writing the script, Carruth studied physics to help him make Abe and Aaron's technical dialogue sound authentic. He took the unusual step of eschewing contrived exposition, and tried instead to portray the shorthand phrases and jargon used by working scientists. This philosophy carried over into production design. The time machine itself is a plain gray box, with a distinctive electronic "hum" created by overlaying the sounds of a mechanical grinder and a car engine, rather than by using a processed digital effect. Carruth also set the story in unglamorous industrial parks and suburban tract homes.[4]

Carruth chose to deliberately obfuscate the film's plot to mirror the complexity and confusion created by time travel. As he said in a 2004 interview: "This machine and Abe and Aaron's experience are inherently complicated so it needed to be that way in order for the audience to be where Abe and Aaron are, which was always my hope."[9]

Filming

Principal photography took place over five weeks, on the outskirts of Dallas, Texas.[4] The film was produced on a budget of only USD$7,000,[2] and a skeleton crew of five. Carruth acted as writer, director, producer, cinematographer, editor, and music composer.[11] He also stars in the film as Aaron, and many of the other characters are played by his friends and family. The small budget required conservative use of the Super 16mm filmstock:[4] the carefully limited number of takes resulted in an extremely low shooting ratio of 2:1. Every shot in the film was meticulously storyboarded on 35mm stills.[9] Carruth created a distinctive flat, overexposed look for the film by using fluorescent lighting, non-neutral color temperatures, high-speed film stock, and filters.[4]

After shooting, Carruth took two years to fully post-produce Primer. He has since said that this experience was so arduous that he almost abandoned the film on several occasions.[9]

Music

The entire film score was created by Carruth. On October 8, 2004, the Primer score was released on Amazon[12] and iTunes.

Release

Distribution

Carruth secured a North American distribution deal with THINKFilm after the company's head of theatrical distribution, Mark Urman, saw the film at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival.[13] Although he and Carruth made a "handshake agreement" during the festival, Urman reported that the actual negotiation of the deal was the longest he had ever been involved with, in part due to Carruth's specific demands over how much control over the film he would retain.[13] The film went on to take $424,760 at the box office.[14]

Critical reception

Primer received positive reception from critics. Review aggregator Metacritic rated it a 68[15] while Rotten Tomatoes rated it a "Fresh" 73%, stating "Dense, obtuse, but stimulating, Primer is a film ready for viewers ready for a cerebral challenge",[16] and the site listed it as one of the best science fiction films "for the thinking man (...or woman)".[17]

Many reviewers were impressed by the film's originality. Dennis Lim of The Village Voice said that it was "the freshest thing the genre has seen since 2001",[18] while in The New York Times, A. O. Scott wrote that Carruth had "the skill, the guile and the seriousness to turn a creaky philosophical gimmick into a dense and troubling moral puzzle".[19] Scott also enjoyed the film's realistic depiction of scientists at work, saying that Carruth had an "impressive feel for the odd, quiet rhythms of small-scale research and development".[19]

There was also praise for Carruth's ability to maintain high production values on a minuscule budget, with Roger Ebert declaring: "The movie never looks cheap, because every shot looks as it must look."[20] Ty Burr of The Boston Globe commented that "aspects of Primer are so low-rent as to evoke guffaws", but added that "the homemade feel is part of the point".[21]

The film's experimental plot and dense dialogue were controversially received. Esquire's Mike D'Angelo claimed that "anybody who claims he fully understands what's going on in Primer after seeing it just once is either a savant or a liar".[22] Scott Tobias writes for The A.V. Club: "The banter is heavy on technical jargon and almost perversely short on exposition; were it not for the presence of voiceover narration, the film would be close to incomprehensible."[5] For the Los Angeles Times, Carina Chocano writes: "sticklers for linear storytelling are bound to be frustrated by narrative threads that start promisingly, then just sort of fall off the spool".[23] Some reviewers were entirely put off by the film's obfuscated narrative. Kirk Honeycutt of The Hollywood Reporter complained that Primer "nearly gets lost in a miasma of technical jargon and scientific conjecture".[15]

"Primer is hopelessly confusing and grows more and more byzantine as it unravels," Chuck Klosterman writes in an essay on time travel films five years later. "I've watched it seven or eight times and I still don't know what happened." He nonetheless says it is "the finest movie about time travel I've ever seen" because of its realism:

It's not that the time machine ... seems more realistic; it's that the time travelers themselves seem more believable. They talk and act (and think) like the kind of people who might accidentally figure out how to move through time, which is why it's the best depiction we have of the ethical quandaries that might result from such a discovery.

Ultimately, Klosterman says, the lesson of Primer regarding time travel is that "it's too important to use only for money, but too dangerous to use for anything else".[24]

The film has been selected to be part of The A.V. Club's New Cult Canon.[5] Donald Clarke, film critic with The Irish Times, included Primer at No. 20 on his list of the top twenty films of the decade (2000–2010).[25][26] Science fiction author Greg Egan described it as "an ingenious, tautly constructed time-travel story".[27]

Awards

- Grand Jury Prize, Sundance Film Festival in 2004.[28]

- Alfred P. Sloan Prize for films dealing with science and technology, the 2004 Sundance Film Festival.[28]

- Best Writer/Director (Shane Carruth) at the Nantucket Film Festival in 2004.[29]

- Best Feature at the London International Festival of Science Fiction in 2005.[30]

See also

References

- ↑ "PRIMER (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. July 29, 2005. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Mitchell, Wendy. "Shane Carruth on "Primer"; The Lessons of a First-Timer". indieWIRE.com. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ↑ "Primer (2004)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. June 19, 2005. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Primer Production Information". E.D. Distribution. Retrieved 2013-10-15.

- 1 2 3 Tobias, Scott (2008-04-01). "The New Cult Canon: Primer". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ↑ Scott Macaulay (2016). "Shane Carruth's Primer: Tech Support". The Magazine of Independent Film. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ↑ "In the Loop: Shane Carruth's Primer". Electric Sheep Magazine (UK). 25 October 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Carruth Q&A". E.D. Distribution. Retrieved 2013-10-15.

- 1 2 3 4 Murray, Rebecca (2004-10-22). "Interview with Shane Carruth". About.com. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ↑ "A Primer Primer". The Village Voice. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ↑ Primer at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Primer Score". Amazon. 2004-10-08. Retrieved 2009-05-29.

- 1 2 Taubin, Amy. "Primer: The New Whiz Kid on the Block". Film Comment. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ Box Office Mojo - Primer Domestic Total Gross Retrieved 2012-2-11

- 1 2 "Primer". Metacritic. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ↑ "Primer". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ↑ Jeff Giles. "Ten Sci-Fi Flicks for the Thinking Man". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ↑ Lim, Dennis (2004-09-28). "36-Hour Party People". The Village Voice. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- 1 2 Scott, A. O. (2004-10-08). "From a Suburban Garage, a New Take on Time Travel". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (2004-10-29). "Reviews: Primer". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ↑ Burr, Ty (2004-10-15). "'Primer' is an entertaining overload of techno possibilities". The Boston Globe. NY Times Co. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ↑ D'Angelo, Mike (2004-11-01). "The Best Movie We've Seen Since Tomorrow". Esquire. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ Chocano, Carina (2004-10-22). "Reviews: Primer". The Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Klosterman, Chuck (2009). Eating the Dinosaur. New York, NY: Scribner. pp. 63–66. ISBN 978-1-4165-4421-0.

- ↑ Clarke, Donald (1 December 2009). "There will be rows: Donald Clarke's top 20 films". The Irish Times. p. 18. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ↑ Wilonsky, Robert (December 18, 2009). "Shane Carruth's Locally Made Primer Makes at Least One Critic's Best-of-the-Decade List". Dallas Observer.

- ↑ Egan, Greg (2015-06-12). "No Intelligence Required". Retrieved 2015-10-13.

- 1 2 "Sundance Film Festival: Films Honoured 1985-2007" (PDF). Sundance Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-14. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ↑ "Awards and Nominations; Critical Acclaim". Primer website. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ "Awards History". The London International Festival of Science Fiction and Fantastic Film. Archived from the original on 2008-03-30. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Primer (film) |

- Official website

- Primer at the Internet Movie Database

- Primer at Box Office Mojo

- Primer at Rotten Tomatoes

- Primer at Metacritic

- Primer timelines

- Village Voice interview with Shane Carruth.

- Allen, Mark. "Filming Locations for the Movie Primer". MarkAllenCam.com.

- Primer: The Perils and Paradoxes of Restricted Time Travel Narration

- Sports, Repetition, and Control in Shane Carruth's Primer

- Re-Membering the Time-Travel Film: From La Jetée to Primer

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by American Splendor |

Sundance Grand Jury Prize: U.S. Dramatic 2004 |

Succeeded by Forty Shades of Blue |

| Preceded by Dopamine |

Alfred P. Sloan Prize Winner 2004 |

Succeeded by Grizzly Man |