Purple-faced langur

| Purple-faced langur[1] | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Purple-faced langur, subspecies T. v. philbricki | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Family: | Cercopithecidae |

| Genus: | Trachypithecus |

| Species: | T. vetulus |

| Binomial name | |

| Trachypithecus vetulus (Erxleben, 1777) | |

| |

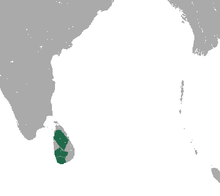

| Purple-faced Langur range | |

The purple-faced langur (Trachypithecus vetulus), also known as the purple-faced leaf monkey, is a species of Old World monkey that is endemic to Sri Lanka. The animal is a long-tailed arboreal species, identified by a mostly brown appearance, dark face (with paler lower face) and a very shy nature. The species was once highly prevalent, found in suburban Colombo and the "wet zone" villages (areas with high temperatures and high humidity throughout the year, whilst rain deluges occur during the monsoon seasons),[3] but rapid urbanization has led to a significant decrease in the population level of the monkeys. Known as ශ්රී ලංකා කලු වදුරා in Sinhala.

Taxonomy & Description

There are four distinct subspecies, (or sometimes 5) of purple-faced langur:

- Southern lowland wetzone purple-faced langur, Trachypithecus vetulus vetulus

- Western purple-faced langur or north lowland wetzone purple-faced langur, Trachypithecus vetulus nestor

- Dryzone purple-faced langur, Trachypithecus vetulus philbricki

- Montane purple-faced langur or Bear Monkey, Trachypithecus vetulus monticola

- Northern purple-faced langur, Trachypithecus vetulus harti (not yet given validity)

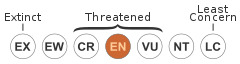

All four subspecies exhibit different cranial and pelage characteristics, as well as body size. The western purple-faced langur is one of the 25 most endangered primates in the world.[4] Most groups of langurs contain only one adult male.[5][6]

Males are usually larger than females. Black to grayish brown coats, and whitish to gray short 'trousers' rounded off by purplish-black faces with white sideburns. Part of the back is covered with whitish fur, and tail is also furred with black and white mixed colors. Feet, and hands are also purplish-black in color. It is the largest primate in Sri Lanka, usually leading males of the group are larger than usual Tufted gray langur that lived together in the habitats. Bear monkey has more dark black coat and usually with heavy moustache. Hair of crown directed backwards throughout, not radiating. it lacks the crest of Grey Langur. Hair of crown not longer than on temples and nape. Rump is pure white or whitish gray.

.jpg)

According to the Mammals of Sri Lanka, the 4 subspecies are recognized as follows.[7]

- Trachypithecus vetulus vetulus - "Color varies greatly. Black upper torso, light brown cap, well defined silvery rump patch that extends to legs. Prominent white whiskers. Tail is also white colored. Many white morphs are observed in this subspecies. They can be all-white to partly white leucistic."

- Trachypithecus vetulus nestor - "It is the smallest of all subspecies. Upper torso dark grayish brown with light grayish brown rump patch, darker grayish brown legs and white cap."

- Trachypithecus vetulus philbricki - "Largest subspecies. Grayish brown torso, ill-defined grayish rump patch, dark cap. Prominent white cheeks with tufts. Exceptionally long slimy tail."

- Trachypithecus vetulus monticola - "Dark gray brown coat. Large but ill-defined grayish rump patch. Prominent white cheek tufts, light brownish gray cap. Fur long and shaggy due to habitat they live is cold."

A possible subspecies called Trachypithecus vetulus harti is recognized, but not yet given validity. This subspecies is known from some skins found from Jaffna peninsula and north of the Vavuniya. Uniquely, this subspecies has yellowish golden hair on its scalp and a golden sheen to its fur. Otherthan these differences, anatomy and all the other aspects are similar to the Trachypithecus vetulus philbricki.[8]

Habitat

The purple-faced langur is found in closed canopy forests in Sri Lanka's mountains and the southwestern part of the country, known as the "wet zone". Only 19% of Sri Lanka consists of forested areas. This habitat has decreased from 80% in 1980 to ~25% in 2001.[4] Currently this range has decreased to below 3%. The range consists of the most densely populated lowland rainforest areas of Sri Lanka. Deforestation has resulted in the langurs home ranges to be exposed to direct sunlight. Purple-faced langurs are most often found in small and widely scattered groups. Ninety percent of the langurs range, now consists of human populated areas. Populations are critically low within and between sites. Threats to this species include infringement on range by croplands, grazing, changing agriculture, road production, soil loss/erosion and deforestation, poisoning from prevention of crop raiding, and hunting for medicine and food.[5][6]

Its range has constricted greatly in the face of human encroachment, although it can still be seen in Sinharaja, Kitulgala, Kandalama, Mihintale, in the mountains at Horton Plains National Park or in the rainforest city of Galle.

Diet

The purple-faced langur is mostly folivorous, but will also feed on fruits, flowers, and seeds. While they normally avoid human habitations, fruit such as jak (Artocarpus heterophyllus), rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum), banana (Musa balbisiana), and mango (Mangifera indica) may contribute up to 50% to their diet in cultivated areas.[4] In the wild, food such as the fruits of Dimocarpus longan and Drypetes sepiaria are taken. Purple-faced langur digestion is adapted to derive the majority of required nutrients and energy from complex carbohydrates found in leaves, with the help of specialized stomach bacteria.[9] Where the species' diet is currently heavily dependent cultivated fruits, the ability to derive sufficient nutrition may become impaired.[4] Seasonal availability of fruit may serve to increase this effect.[10]

T. vetulus feed on a less diverse diet than S. priam, with a greater proportion of leaves. Food plants that have been identified include Holoptelea integrifolia, Hydnocarpus venenata, Macaranga peltata, Manilkara hexandra, Mikania scandens, Mischodon zeylanica, Pterospermum suberifolium, Tetrameles nudiflora, Vitex altissima, and Wrightia angustifolia.[11]

Communication

Loud calls are often used to distinguish between individual purple-faced langurs. The elements of a call fall into three categories: harsh barks, whoops, and residuals. Individuals can be differentiated by the number of phrases and residuals within a call. Calls occur more often in the morning mostly stimulated by neighboring groups and territorial battles. More calls occur during sunny periods than cloudy. The least amount of calls occur in the evening. Daytime calls usually aid in the defense of home ranges. The loud barking call, particularly of the highland form, can be mistaken for the roar of a predator such as a leopard. Calls of the purple-faced langur differ from those of any of the subspecies. Environmental characters impact call times as well as anthropogenic disturbance. Vocalization can be used to alert members of predators, attract mates, defend territory, and locate group members. Vocalization is extremely important for the use in conservation especially because they are very difficult to observe directly. Adult males are the most vocal among the entire group. Defensive whooping calls are also accompanied by intense visual and locomotive displays. Vocalizations are also helpful in determining taxonomic identification.[6]

Conservation

Some conservation strategies consist of improving management of the already protected areas as well as locate and protect new areas and corridors within ranges. Efforts to help increase populations may help survival. It would be beneficial to lower human-langur conflicts. Rope bridges could be established for langurs to move between ranges safely, which may decrease the crossing of power lines and roads. Replanting pine plantations with native species exploited by these langurs, could possibly increase its preferred habitat as well.[6] Public education of conservation to the local people emphasizing compassion and kindness as well as explaining the importance and necessity of these mammals to the ecosystems overall biodiversity.[5]

References

- ↑ Groves, C.P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 178. OCLC 62265494. ISBN 0-801-88221-4.

- ↑ Dittus, W.; Molur, S. & Nekaris, A. (2008). "Trachypithecus vetulus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ↑ Post-Disaster Housing Coordination Project (August 2007). "Introduction" (PDF). UN-HABITAT: United Nations Human Settlements Programme - Sri Lanka District Housing Profile (Colombo District). UNICEF. p. 3. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Parker, L; V. Nijman; K. A. I. Nekaris (5 August 2008). "When there is no forest left: fragmentation, local extinction, and small population sizes in the Sri Lankan western purple-faced langur". Endangered Species Research. 5: 29–36. doi:10.3354/esr00107.

- 1 2 3 Rudran, Rasanayagam (January 2007). "A survey of Sri Lanka's endangered and endemic western purple-faced langur (Trachypithecus vetulus nestor)". Primate Conservation. 22: 139–144. doi:10.1896/052.022.0115.

- 1 2 3 4 Eschmann, C; R. Moore; K.A.I. Nekaris (2008). "Calling patterns of Western purple-faced langurs (Mammalia: Primates: Cercopithecidea: Trachypithecus vetulus nestor) in a degraded human landscape in Sri Lanka". Contributions to Zoology. 81 (77).

- ↑ Yapa, A.; Ratnavira, G. (2013). Mammals of Sri Lanka. Colombo: Field Ornithology Group of Sri Lanka. p. 1012. ISBN 978-955-8576-32-8.

- ↑ http://www.dilmahconservation.org/animal-profiles/purple-faced-langur/

- ↑ Bauchop, T.; Martucci, R. W. (1968). "The ruminant-like digestion of the langur monkey.". Science. 161: 698–700. doi:10.1126/science.161.3842.698.

- ↑ "Primate Ecology and Behavior Project". Rajnish Vandercone, Arun Bandara, Gihan Jayaweera. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ↑ Rajnish P. Vandercone; Chameera Dinadh; Gayan Wijethunga; Kitsiri Ranawana; David T. Rasmussen (2012). "Dietary Diversity and Food Selection in Hanuman Langurs (Semnopithecus entellus) and Purple-Faced Langurs (Trachypithecus vetulus) in the Kaludiyapokuna Forest Reserve in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka". International Journal of Primatology. 33 (6): 1382–1405. doi:10.1007/s10764-012-9629-9.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Purple-faced langur |

- ARKive - images and movies of the purple-faced langur (Trachypithecus vetulus)

- Video of Purple-faced leaf langur Monkey roaming in Buddhist Hermitage