Prize money

Prize money has a distinct meaning in warfare, especially naval warfare, where it was a monetary reward paid out under prize law to the crew of a ship for capturing or sinking an enemy vessel. The claims for the bounty are usually heard in a Prize Court. This article covers the arrangements of the British Royal Navy, but similar arrangements were used in the navies of other nations, and existed in the British Army and other armies, especially when a city had been taken by storm.

Royal Navy prize money

History

In the 16th and 17th centuries, captured ships were legally Crown property. In order to reward and encourage sailors' zeal at no cost to the Crown, it became customary to pass on all or part of the value of a captured ship and its cargo to the capturing captain for distribution to his crew. (Similarly, all belligerents of the period issued Letters of Marque and Reprisal to civilian privateers, authorising them to make war on enemy shipping; as payment, the privateer sold off the captured booty.)

This practice was formalised via the Cruisers and Convoys Act of 1708. An Admiralty Prize Court was established to evaluate claims and condemn prizes, and the scheme of division of the money was specified. This system, with minor changes, lasted throughout the colonial, Revolutionary, and Napoleonic Wars.

If the prize were an enemy merchantman, the prize money came from the sale of both ship and cargo. If it were a warship, and repairable, usually the Crown bought it at a fair price; additionally, the Crown added "head money" of 5 pounds per enemy sailor aboard the captured warship. Prizes were keenly sought, for the value of a captured ship was often such that a crew could make a year's pay for a few hours' fighting. Hence boarding and hand-to-hand fighting remained common long after naval cannons developed the ability to sink the enemy from afar.

All ships in sight of a capture shared in the prize money, as their presence was thought to encourage the enemy to surrender without fighting until sunk.

The distribution of prize money to the crews of the ships involved persisted until 1918. Then the Naval Prize Act changed the system to one where the prize money was paid into a common fund from which a payment was made to all naval personnel whether or not they were involved in the action. In 1945 this was further modified to allow for the distribution to be made to Royal Air Force (RAF) personnel who had been involved in the capture of enemy ships; however, prize claims had been awarded to pilots and observers of the Royal Naval Air Service since c1917, and later the RAF.

Distribution

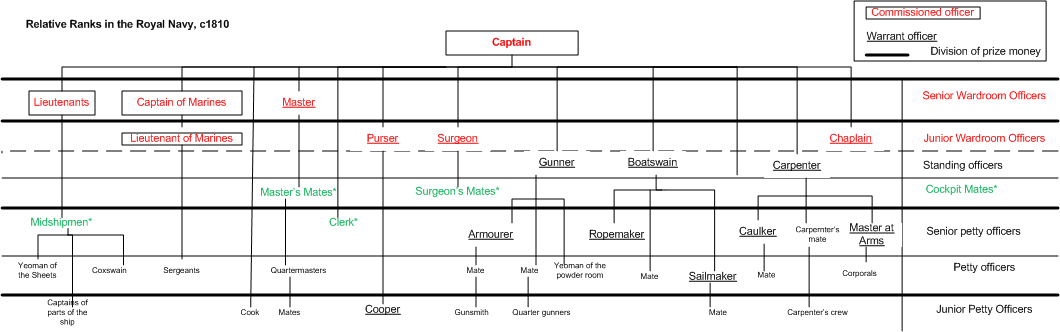

The following scheme for distribution of prize money was used for much of the Napoleonic wars, the heyday of prize warfare. Allocation was by eighths. Two eighths of the prize money went to the captain or commander, generally propelling him upwards in political and financial circles. One eighth of the money went to the admiral or commander-in-chief who signed the ship's written orders (unless the orders came directly from the Admiralty in London, in which case this eighth also went to the captain). One eighth was divided among the lieutenants, sailing master, and captain of marines, if any. One eighth was divided among the wardroom warrant officers (surgeon, purser, and chaplain), standing warrant officers (carpenter, boatswain, and gunner), lieutenant of marines, and the master's mates. One eighth was divided among the junior warrant and petty officers, their mates, sergeants of marines, captain's clerk, surgeon's mates, and midshipmen. The final two eighths were divided among the crew, with able and specialist seamen receiving larger shares than ordinary seamen, landsmen, and boys.[1][2] The pool for the seamen was divided into shares, with each able seaman getting two shares in the pool (referred to as a fifth-class share), an ordinary seaman received a share and a half (referred to as a sixth-class share), landsmen received a share each (a seventh-class share), and boys received a half share each (referred to as an eighth-class share).

Examples

Perhaps the greatest amount of prize money awarded was for the capture of the Spanish frigate Hermione on 31 May 1762 by the British frigate Active and sloop Favourite. The two captains, Herbert Sawyer and Philemon Pownoll, received about £65,000 apiece, while each seaman and Marine got £482-485.[3][4][5]

The prize money from the capture of the Spanish frigates Thetis and Santa Brigada in October 1799, £652,000, was split up among the crews of four British frigates, with each captain being awarded £40,730 and the Seamen each receiving £182 4s 9¾d or the equivalent of 10 years pay.[2]

In January 1807, the frigate Caroline took the Spanish ship San Rafael as a prize, netting Captain Peter Rainier £52,000.[4]

For more on the Prize Court during World War I, see also Maxwell Hendry Maxwell-Anderson.

The crewmen of USS Omaha hold the distinction of being the last American sailors to receive prize money, for capturing the German freighter Odenwald on 6 November 1941, just before America's entry into World War II, though the money would not be awarded until 1947.[6]

References

- ↑

- Lavery, Brian (1989). Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 0-87021-258-3. OCLC 20997619. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- 1 2 Rodger 522-524

- ↑ "Capture of The Hermione". Archived from the original on April 22, 2009. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- 1 2 "Nelson and His Navy - Prize Money". The Historical Maritime Society. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ W.H.G. Kingston. "How Britannia Came to Rule the Waves". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- ↑ Nofi, Al (20 July 2008). "The Last "Prize" Awards in the U.S. Navy?" (205). Strategypage.com. ″Oldenwald was taken to Puerto Rico. An admiralty court ruled that since the ship was illegally claiming American registration, there was sufficient grounds for confiscation. At that point, some sea lawyers got into the act. Observing that the attempt to scuttle the ship was the equivalent of abandoning her, they claimed that the crews of the two American ships had salvage rights, to the tune of $3 million. This led to a protracted court case, which was not settled until 1947.”

Sources

- Rodger, N.A.M. (2005). The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649-1815. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-06050-0.

External links

- Nelson's Navy - Prize Money

- The Gunroom, a discussion site on the Aubrey-Maturin novels with many historical links and resources