Rabbi Meir

Rabbi Meir or Rabbi Meir Baal HaNes (Rabbi Meir the miracle maker) was a Jewish sage who lived in the time of the Mishna. He was considered one of the greatest of the Tannaim of the fourth generation (139-163). According to the Talmud, his father was a descendant of the Roman Emperor Nero who had converted to Judaism. His wife Bruriah is one of the few women cited in the Gemara. He is the third most frequently mentioned sage in the Mishnah.[1]

In the Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Gittin p. 4a, it says that all anonymous Mishnas are attributed to Rabbi Meir. This rule was required because, following an unsuccessful attempt to force the resignation of the head of the Sanhedrin, Rabbi Meir's opinions were noted, but not in his name, rather as "Others say...".[2]

"Meir" may have been a sobriquet. Rabbi Meir's real name is thought to have been Nahori or Misha. The name Meir, meaning "Illuminator," was given to him because he enlightened the eyes of scholars and students in Torah study.[3]

Legend

The sobriquet "Master of the Miracle" is based on the following story. Rabbi Meir was married to Bruriah, the daughter of Rabbi Chananiah ben Teradyon, one of the ten martyrs. The government ordered the execution of the couple for teaching Torah publicly. Bruriah's sister was sent to a brothel. Rabbi Meir took a bag of gold coins and went to the brothel disguised as a Roman horseman. He offered the money as a bribe to the guard. The guard replied, “When my supervisor comes, he will notice one missing and kill me.” Rabbi Meir answered, “Take half the money for yourself, and use the other half to bribe the officials.” The guard continued, “And when there is no more money, and the supervisors come - then what will I do?” Rabbi Meir answered:

(Eloha d'Meir aneini, אלהא דמאיר ענני)

The guard asked, “And how can I be guaranteed that this will save me?” Rabbi Meir replied, “Look - there are man-eating dogs over there. I will go to them and you will see for yourself.” Rabbi Meir walked over the dogs and they ran over to him to tear him apart. He cried, “God of Meir - answer me!” and the dogs retreated. The guard was convinced and gave him the girl. When the group of supervisors came, the guard bribed them with the money. When the money was used up, they arrested the guard and sentenced him to death by hanging. When they tied the rope around his neck, he said, “God of Meir - answer me!” and the rope tore.[4]

From then on, a tradition developed that a Jew in crisis gives charity in memory of Rabbi Meir. He then says, “God of Meir - answer me!" Various charitable foundations have been named for Rabbi Meir and include the Rabbi Meir Baal HaNeis Salant charity founded in 1860 by Rabbi Shmuel Salant and the 'Colel Chabad Rabbi Meir Ba'al HaNes' charity founded by Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi in 1788. Some say the above and give a small amount of charity, as a way to recover a lost item.[5]

Talmudic references

In the Gemara to tractate Erubin in the Babylonian Talmud there is an extended discussion of the real name of this Rabbi Meir. At 13b there is, without argumentation, a simple statement that this Rabbi Meir is "Eleazar Ben Arach," one of the students of Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakai. This Eleazar ben Arach is given tremendous praise in Avot of Rabbi Natan. Indeed, at 2:8 of Rabbi Nathan's "Avot" this Eleazar ben Arach is presented as being the greatest of the Sages, inclusive of Rabbi Eliezer ha Gadol. Further in the Gemara to tractate Haggigah in the Babylonian Talmud [14b] this same Eleazar ben Arach is presented as a student of Rabbi Yochanan Ben Zakai who, at an early age, had mastered the meaning of the mystical revelations which are associated with "the Work of the Chariot."

In " 'The Written' as the Vocation of Conceiving Jewishly"[6] this conundrum is addressed. The suggestion is that the virtual disappearance of Eleazer Ben Arach from Rabbinic ways allowed for the usage of this name as a cognomen for Rabbi Meir, acceptably to Rabbinic officialdom who permitted this "cover name" to honor this great scholar but with sufficient indirectness so as not also to honor his checkered history with Rabbinic officialdom. The book also points out that Rabbi Yochanan Ben Zakai set up a bet midrash at Beor Khail after he left Yavneh, apparently because he was so radically shamed and discredited by what would become the mainstream of the Rabbinic Movement after "that very day" memorialized in Chapter Five of the Mishna's tractate Sotah.[7] Rabbi Meir was not a student of Zakai at Yavneh. But it is argued that it is entirely possible that he became a student of Zakai at Beor Khail.

In his notations on Talmud (Mesoras Has'Shas), Rabbi Yeshayah Berlin points out that the Nehorai that is identified with Rabbi Eleazar is not Rabbi Meir but a different Tanna called Nehorai. In which case there is no need for the hypothesis mentioned above.[8]

First a disciple of Elisha ben Abuyah and later of Rabbi Akiva, Rabbi Meir was one of the most important Tannaim of the Mishnah. Rabbi Akiva's teachings, through his pupil Rabbi Meir, became the basis of the Mishnah. Rabbi Meir is the quoted authority for many Aggadot and Halachot that are still studied today. Also, Rabbi Meir was an active participant in Bar Kokhba's revolt.[3]

Twenty four thousand students of Rabbi Akiva died in a plague. Only five survived, and Rabbi Meir was one of them. The four others were: Rabbi Judah ben Ilai, Rabbi Eleazar ben Shammua, Rabbi Jose ben Halafta, and Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai.[9]

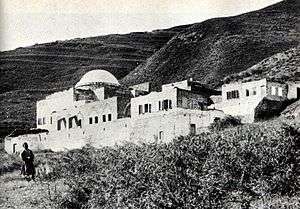

Tomb in Tiberias

Although Rabbi Meir died outside of the Land of Israel, he was brought to Tiberias (the same city where his well-known teacher Rabbi Akiva is buried) and buried there in a standing position near the Kinneret. It is said that he asked to be buried this way so when the Final Redemption occurs, Rabbi Meir would be spared the trouble of arising from his grave and could just walk out to greet the Jewish Messiah. [10] He requested that he be buried in Eretz Yisrael by the seashore so that the water that washes the shores should also lap his grave (Jerusalem Talmud, Kelaim 9:4). Visitors to his grave traditionally recite Tehillim and a special prayer. Every year, thousands of Jews make pilgrimage to his grave to receive blessings for health and success, in particular on his yahrtzeit (anniversary of his death) the 14th of Iyar, which is also Pesach Sheni (known as the holiday of the 'second chance').[3]

Four tombs in Palestine and one or two in Iraq have over time been associated with Rabbi Meir.[11] The 12th century visitors Benjamin of Tudela and Petachiah of Regensburg favored the Iraqi option and did not mention a tomb near Tiberias.[11] The first clear mention of a tomb of Rabbi Meir in this place was made in the early 13th century by Samuel ben Samson, but he also mentioned a tomb of Rabbi Meir in Jish, as did many other writers in the following centuries.[11] There was also until the 16th century some disagreement over which Rabbi Meir was buried here.[11] For example, Moses ben Mordecai Bassola, while noting the story that the person here was buried standing up, stated explicitly that it was a Rabbi Meir different than the tanna.[11] However, from sometime in the 16th century there has been general agreement that Rabbi Meir the tanna has his tomb here.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Drew Kaplan, "Rabbinic Popularity in the Mishnah VII: Top Ten Overall [Final Tally] Drew Kaplan's Blog (5 July 2011).

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Tractate Horayot 13b-14a

- 1 2 3 http://www.jewishbless.com/pages/rabbi.html

- ↑ http://judaicaplus.com/tzadikim/tz_viewer.cfm?page=meir.htm&t=Rabbi%20Meir%20Ba'al%20HaNess

- ↑ http://people.eju.org/person/rabbi-meir-rabbi-meir-baal-hanes

- ↑ McGinley, 2006; pages 408-409.

- ↑ 2006; pages 114-223. See Mishnah Sotah, Ch. 5.

- ↑ See Emet L' Yaakov ([Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetzky) to Eiruvin 13b for an explanation on the symbolism of the two names Meir and Nehorai.

- ↑ Talmud Bavli Yevamot 62b.

- ↑ Tiberias - Walking with the sages in Tiberias

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dan Ben-Amos (2006). Folktales of the Jews. 1. Jewish Publication Society. pp. 73–78.

External links

- Rabbi Meir Baal HaNess charity

- Rabbi Meir Ba'al HaNess Biography

- Master of Miracles

- Photos of Rabbi Meir's tomb and synagogue in Tiberias

- Reb Meyer Baal HaNes Charity

- Rabbi Meir Baal HaNeis Salant charity

- Rabbi Meir Baal HaNes

- Who Was Rabbi Meir? by Dr. Henry Abramson