Rainilaiarivony

| Rainilaiarivony | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of Madagascar | |

|

In office 1864–1895 | |

| Preceded by | Rainivoninahitriniony |

| Succeeded by | Rainitsimbazafy |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

30 January 1828 Ilafy, Madagascar |

| Died |

17 July 1896 (aged 68) Algiers, French Algeria |

| Spouse(s) |

|

Rainilaiarivony (30 January 1828 – 17 July 1896) was the Prime Minister of Madagascar from 1864 to 1895, succeeding his older brother Rainivoninahitriniony, who had held the post for thirteen years. His career mirrored that of his father Rainiharo, a renowned military man who became Prime Minister during the reign of Queen Ranavalona I. Despite a childhood marked by ostracism from his family, as a young man Rainilaiarivony was elevated to a position of high authority and confidence in the royal court, serving alongside his father and brother. He co-led a critical military expedition with Rainivoninahitriniony at the age of 24 and was promoted to Commander-in-Chief of the army following the death of the queen in 1861. In that position he oversaw continuing efforts to maintain royal authority in the outlying regions of Madagascar and acted as adviser to his brother, who had been promoted to Prime Minister in 1852. He also influenced the transformation of the kingdom's government from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional one, in which power was shared between the sovereign and the Prime Minister. Rainilaiarivony and Queen Rasoherina worked together to depose Rainivoninahitriniony for his abuses of office in 1864. Taking his brother's place as Prime Minister, Rainilaiarivony remained in power for the next 31 years by marrying three queens in succession: Rasoherina, Ranavalona II and Ranavalona III.

As Prime Minister, Rainilaiarivony actively sought to modernize the administration of the state, in order to strengthen and protect Madagascar against the political designs of the British and French colonial empires. The army was reorganized and professionalized, public schooling was made mandatory, a series of legal codes patterned on English law were enacted and three courts were established in Antananarivo. The statesman exercised care not to offend traditional norms, while gradually limiting traditional practices, such as slavery, polygamy, and unilateral repudiation of wives. He legislated the Christianization of the monarchy under Ranavalona II. His diplomatic skills and military acumen assured the defense of Madagascar during the Franco-Hova Wars, successfully preserving his country's sovereignty until a French column captured the royal palace in September 1895. Although holding him in high esteem, the French colonial authority deposed the Prime Minister and exiled him to French Algeria, where he died less than a year later in August 1896.

Early life

Rainilaiarivony was born on 30 January 1828 in the Merina village of Ilafy, one of the twelve sacred hills of Imerina, into a family of statesmen. His father, Rainiharo, was a high-ranking military officer and a deeply influential conservative political adviser to the reigning monarch, Queen Ranavalona I, at the time that his wife, Rabodomiarana (daughter of Ramamonjy), gave birth to Rainilaiarivony.[1] Five years later Rainiharo was promoted to the position of Prime Minister, a role he retained from 1833 until his death in 1852. During his tenure as Prime Minister, Rainiharo was chosen by the queen to become her consort, but he retained Rabodomiarana as his wife according to local customs that allowed polygamy. Rainilaiarivony's paternal grandfather, Andriatsilavo, had likewise been a privileged adviser to the great King Andrianampoinimerina (1787–1810).[2] Rainilaiarivony and his relatives issued from the Andafiavaratra family clan of Ilafy who, alongside the Andrefandrova clan of Ambohimanga, constituted the two most influential hova (commoner) families in the 19th-century Kingdom of Imerina. The majority of political positions not assigned to andriana (nobles) were held by members of these two families.[3]

According to oral history, Rainilaiarivony was born on a day of the week traditionally viewed as inauspicious for births. Custom in much of Madagascar dictated that such unlucky children had to be subjected to a trial by ordeal, such as prolonged exposure to the elements, since it was believed the misfortune of their day of birth would ensure a short and cursed life for the child and its family. But rather than leave the child to die, Rainilaiarivony's father reportedly followed the advice of an ombiasy (astrologer) and instead amputated a joint from two fingers on his infant son's left hand to dispel the ill omen. The infant was nonetheless kept outside the house to avert the possibility that evil might still befall the family if the child remained under their roof. Relatives took pity and adopted Rainilaiarivony to raise him within their own home. Meanwhile, Rainilaiarivony's older brother Rainivoninahitriniony enjoyed the double privilege of his status as elder son and freedom from a predestined evil fate. Rainiharo selected and groomed his elder son to follow in his footsteps as Commander-in-Chief and Prime Minister, while Rainilaiarivony was left to make his way in the world by his own merits.[2]

At age six, Rainilaiarivony began two years of study at one of the new schools opened by the London Missionary Society (LMS) for the children of the noble class at the royal palace in Antananarivo. Ranavalona shut down the mission schools in 1836, but the boy continued to study privately with an older missionary student. When Rainilaiarivony reached age 11 or 12, the relatives who had raised him decided he was old enough to make his own way in the world. Beginning with the purchase and resale of a few bars of soap, the boy gradually grew his business and expanded into the more profitable resale of fabric. The young Rainilaiarivony's reputation for tenacity and industriousness, as he fought against his predestined misfortunes, eventually reached the palace, where at the age of 14 the boy was invited to meet Queen Ranavalona I. She was favorably impressed, awarding him the official ranking of Sixth Honor title of Officer of the Palace. At 16 he was promoted to Seventh Honor, then promoted twice again to Eighth and Ninth Honor at age 19, an unprecedented ascent through the ranks.[4]

As a regular among the foreigners at the palace, young Rainilaiarivony was tasked by an English merchant as a courier for his confidential business correspondence. The merchant was impressed by the young man's punctuality and integrity and would regularly refer to him as the boy who "deals fair." With the addition of the Malagasy honorific "ra", the expression was transformed into a sobriquet—"Radilifera"—that Rainilaiarivony adopted for himself and transmitted to a son and grandson. The arrival of a doctor from Mauritius in 1848 provided Rainilaiarivony with the opportunity to study medicine over the course of three years. With this knowledge he became indispensable at the palace, where he provided modern medical care to the Queen and other members of the aristocracy. Successfully curing the Queen of a particularly grievous illness earned him a promotion to Tenth Honor in April 1851, thereby qualifying him for more responsible positions within the monarch's closest circle.[5] Rainiharo took advantage of this trust to successfully encourage friendship between his own sons and the only child and heir apparent of the queen, her son Radama II, who was one year Rainilaiarivony's junior.[6]

Marriage and family

Around 1848—the exact date of his marriage is not recorded—Rainilaiarivony, then around 20 or 21 years old and having adopted the name Radilifera, concluded a marriage with his paternal cousin Rasoanalina. She bore him sixteen children over the course of their marriage. In addition, a one-year-old son that Rasoanalina had conceived with another man prior to the union, Ratsimatahodriaka (Radriaka), was adopted by Rainilaiarivony as his own. As a young man, Ratsimatahodriaka was groomed by Rainilaiarivony to become his successor, but the youth fell from a balcony while intoxicated and died in his early twenties.[7]

Most of Rainilaiarivony's children failed to achieve their full potential. One son, Rafozehana, died young of delirium tremens, and sons Ratsimandresy and Ralaiarivony both met violent ends while still in their youth.[7] Randravalahy, to whom Rainilaiarivony later ascribed the name Radilifera, was sent to France to study but returned before earning his diploma and faded into obscurity among the upper classes of Imerina. Ramangalahy studied medicine and was on his way to becoming a successful doctor, but died of illness in his twenties. Three brothers turned to crime: Rajoelina, who violated the laws of his country to enrich himself by selling contraband gold to an English company; Penoelina, who studied in England before health issues recalled him to Madagascar, where he and his friends engaged in sexual assault and theft; and Ramariavelo (Mariavelo), who organized a group of bandits to rob the houses of common citizens. One of Rainilaiarivony's daughters died in her twenties following a self-induced abortion, and the rest married and lived quiet lives out of public view.[8]

Military career

The February 1852 death of Prime Minister Rainiharo left the queen without her consort, long-time political adviser and military Commander-in-Chief. She consequently awarded Rainilaiarivony a double promotion to Twelfth Honor ten days afterward, in preparation for an increase in military and political responsibilities.[5] Shortly thereafter the queen expressed romantic interest in Rainilaiarivony and proposed that he assume the former role of his father as prince consort and Prime Minister. The young man refused on the double basis of their age difference, the queen being forty years his senior, as well as the perceived impropriety of becoming intimate with his father's former lover. Ranavalona continued to harbor feelings for him throughout her lifetime but she did not express resentment over his refusal to reciprocate them[9] and went on to take another high-ranking official as consort: Rainijohary, who was jointly awarded the role of Prime Minister along with the new Commander-in-Chief, Rainivoninahitriniony.[10] Within a year the queen had assigned the 24-year-old Rainilaiarivony to his first position of responsibility within the military,[5] and promoted him to Royal Secretary, keeper of the Royal Seal, and supervisor to the Royal Treasurer.[9]

Several years prior to his death, former Prime Minister Rainiharo had led military campaigns to bring the peoples of the south under Merina control. Strong military campaigns on both sides of the conflict had concluded in a peace agreement between the Merina armies and those of the Bara people of the central southern highlands, who were accorded semi-autonomous status in exchange for serving as a buffer between the Sakalava to the west and the Tanala, Antemoro, Antefasy and other ethnic groups to the southeast. Upon learning of Rainiharo's death, disgruntled southeastern factions rose up against the Merina military stationed at posts within their territory. Queen Ranavalona responded by sending Rainivoninahitriniony and Rainilaiarivony on their first military expedition to liberate the besieged Merina colonists and quell the uprising.[11]

Under the brothers' joint command were ten thousand soldiers armed with muskets and another thousand carrying swords. An additional 80,000 porters, cooks, servants and other support staff accompanied the army throughout the massive campaign. Over 10,000 were killed by Merina soldiers in the campaign, and according to custom numerous women and children were captured to be sold into slavery in Imerina. Rainilaiarivony took 80 slaves, while his older brother took more than 160. However, the campaign was only partly successful in pacifying the region and the Merina hold over the outlying areas of the island remained tenuous throughout the 19th century.[11]

First thwarted coup attempt

As the queen's son Radama grew to adulthood, he became increasingly disillusioned by the high death toll of his mother's military campaigns and traditional measures of justice, and was frustrated by her unilateral rejection of European influence. The young prince developed sympathetic relationships with the handful of Europeans permitted by Ranavalona to frequent her court, namely Jean Laborde and Joseph-François Lambert, with whom he privately concluded the lucrative Lambert Charter. The charter, which would come into effect upon Radama's accession to the throne, granted Lambert large tracts of land and exclusive rights to road construction, mineral extraction, timber harvesting and other activities on the island. In May 1857, when Rainilaiarivony was 29 years old, Lambert consequently invited Prince Radama, Rainivoninahitriniony, Rainilaiarivony and a number of other officers to conspire with him in a plot to overthrow Ranavalona.[12]

On the eve of the coup, Rainivoninahitriniony informed Lambert that he could not guarantee the support of the army and that the plot should be aborted. One of the officers believed the brothers had betrayed them and sought to exonerate himself by notifying the queen of the failed conspiracy. She reacted by expelling the foreigners from the island and subjecting all the implicated Merina officers to the tangena ordeal in which they were forced to swallow a poison to determine their guilt or innocence. Rainilaiarivony and his brother were excepted from this and remained, like her son Radama, in the queen's confidence for the few remaining years of her life.[12]

Second thwarted coup attempt

In the summer of 1861, when Rainilaiarivony was 33 years old, Queen Ranavalona's advanced age and acute illness produced speculation about who would succeed her. Ranavalona had repeatedly stated her intention that her progressive and pro-European son, Radama II, would be her successor, much to the chagrin of the conservative faction at court. The conservatives privately rallied behind the queen's nephew and adoptive son Ramboasalama, whom the queen had initially declared heir apparent some years prior, and who had never abandoned hope to one day reclaim the right that had briefly been accorded to him.[13]

According to custom, pretenders to the throne had historically been put to death upon the naming of a new sovereign. Radama was opposed to this practice and asked the brothers to help ensure his accession to the throne with minimum bloodshed on the day of the queen's death. Rainilaiarivony successfully maintained authority over the palace guards anxiously awaiting the command from either faction to slaughter the other. When the queen's attendant quietly informed him that her final moments were approaching, Rainilaiarivony discreetly summoned Radama and Rainivoninahitriniony from the Prime Minister's palace to the royal Rova compound and ordered the prince crowned before the gathered soldiers, just as the queen was pronounced dead. Ramboasalama was promptly escorted to the palace where he was obliged to publicly swear allegiance to King Radama.[14]

Rainilaiarivony was made responsible for the tribunal where Ramboasalama's supporters were tried, convicted of subversion and sentenced to banishment and other punishments.[13] Ramboasalama was sent to live with his wife Ramatoa Rasoaray—Rainilaiarivony's sister—in the distant highland village of Ambohimirimo, where he died in April 1862. Rainijohary, the former Prime Minister and consort of Ranavalona, was relieved of his rank and exiled, leaving his co-minister Rainivoninahitriniony as the sole Prime Minister. At the same time, Rainilaiarivony was promoted by Radama to the position of Commander-in-Chief of the military.[15]

Creation of a limited monarchy

Rainilaiarivony—'the Father of the One Who Has the Flower'—was, indeed, a queen-maker; he selected, elevated, and married the last three, beginning with Rasoherina.

— Arthur Stratton, The Great Red Island (1964)[16]

As Commander-in-Chief, Rainilaiarivony maintained a distance from politics throughout the reign of the new monarch, Radama II, instead preferring to focus on his military responsibilities.[17] Meanwhile, disputes between Prime Minister Rainivoninahitriniony and King Radama grew frequent as the young sovereign pursued radical reforms that had begun to foment displeasure among the traditional masses. The situation came to a head on 7 May 1863, when Radama insisted on legalizing duels, despite widespread concern among the king's advisers that the innovation would lead to anarchy. The Prime Minister initiated the arrest of the menamaso, the prince's influential advisers, while Rainilaiarivony enacted his brother's instructions to keep the peace in the capital city. However, the situation deteriorated in dramatic fashion and, by the morning of 12 May, King Radama II was declared dead, having been strangled on the Prime Minister's orders.[18]

Not having been involved in the coup d'état, Rainilaiarivony provided direction for his brother and the rest of the court as they grappled with the gravity of their acts. He proposed that future monarchs would no longer have absolute power but would instead rule by the consent of the nobles. A series of terms were proposed by Rainilaiarivony that the nobles agreed to impose on Radama's widow, Rasoherina. Under Rainilaiarivony's new monarchy, a sovereign required the consent of the nobles to issue a death sentence or promulgate a new law, and was forbidden to disband the army. The new power sharing agreement was concluded by a political marriage between the queen and the Prime Minister.[18]

Because of the new limitations placed on future Merina monarchs by Rainilaiarivony and the Hova courtiers, Radama's strangling represented more than a simple coup d'état. The ruling conditions imposed on Rasoherina reflected a power shift toward the oligarchs of the Hova commoner class and away from the Andriana sovereigns, who had traditionally drawn their legitimacy from the deeply held cultural belief that the royal line was imbued with hasina, a sacred authority bestowed by the ray aman-dreny (ancestors). In this respect, the new political structure in Imerina embodied the erosion of certain traditional social values among the Merina elite, who had gained exposure to contemporary European political thought and assimilated a number of Western governance principles. It also signalled the expansion of a rift between the pro-European, progressive elite to which Rainilaiarivony and his brother belonged, and the majority of the population in Madagascar, for whom traditional values such as hasina remained integral to determining the legitimacy of a government—a divide that would deepen in the decades to come through Rainilaiarivony's efforts to effect a modernizing political and social transformation on a nationwide scale.[19]

Tenure as Prime Minister

Rise to power

Rainivoninahitriniony's tenure as sole Prime Minister was short lived. His violent tendencies, irritability and insolence toward Rasoherina, in addition to lingering popular resentment over Rainivoninahitriniony's role in the violent end to Radama's rule, gradually turned the opinion of the nobles against him. As Commander-in-Chief, Rainilaiarivony attempted to counsel his brother, while simultaneously overseeing diplomatic and military efforts to re-pacify the agitated Sakalava and other peoples, who viewed the coup as an indication of weakening Merina control. The Prime Minister repaid these efforts by repeatedly castigating high-ranking officers and even threatening Rainilaiarivony with his sword.[20]

Two of Rainilaiarivony's cousins urged him to take his elder brother's place in order to end the shame that Rainivoninahitriniony's behavior was bringing upon their family. After weighing the idea, Rainilaiarivony approached Rasoherina with the proposal. The queen readily consented and lent her assistance in rallying the support of the nobles at court. On 14 July 1864, little more than a year after the coup, Rasoherina deposed and divorced Rainivoninahitriniony, then exiled the fallen minister the following year. Rainilaiarivony was promoted to Prime Minister.[20] The arrangement was sealed when Rainilaiarivony took Rasoherina as his bride and demoted his longtime spouse Rasoanalina to the status of second wife. Rainilaiarivony confided in a friend shortly before his death that he deeply loved his first wife and came to share the same degree of feeling toward Rasoherina as well, but never developed the same affection for the subsequent queens he married.[21] None of his royal spouses bore him any children.[22]

By taking this new role, Rainilaiarivony became the first Hova to concurrently serve as both Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief.[20] The sociopolitical transformation that had been triggered by the strangling of Radama II reached its zenith with Rainilaiarivony's consolidation of administrative power. Rasoherina and her successors remained the figureheads of traditional authority, participated in political councils and provided official approval for policies. The Prime Minister issued new policies and laws in the Queen's name.[23] However, the day-to-day governance, security and diplomatic activities of the kingdom principally originated with, and were managed by, Rainilaiarivony and his counselors. This new level of authority enabled the Prime Minister to amass a vast personal fortune, whether through inheritance, gifts or purchase, including 57 houses, large plantations and rice paddies, numerous cattle and thousands of slaves.[24] The most prominent of Rainilaiarivony's properties was the Andafiavaratra Palace, constructed for him on the slope just below the royal Rova compound by English architect William Pool[25] in 1873.[26]

Policies and reforms

Government administration and bureaucracy was strengthened under Rainilaiarivony's leadership. In March 1876, Rainilaiarivony established eight cabinet ministries to manage foreign affairs, the interior, education, war, justice, commerce and industry, finance, and legislation.[27] State envoys were installed throughout the island's provinces to manage administrative affairs, ensure the application of law, collect taxes and provide regular reports back to Antananarivo on the local state of affairs.[28] The traditional method of tax collection through local administrators was expanded in the provinces, bringing in new revenues, most commonly in the form of locally produced goods such as woven mats, fish, or wood.[23] Rainilaiarivony actively encouraged Merina settlement in the coastal provinces, but coastal peoples were not invited to participate in political administration of the territories they inhabited. Approximately one third of the island had no Merina presence and retained de facto independence from the authority of the crown, including parts of the western provinces of Ambongo and Menabe, and areas in the southern Bara, Tanala, Antandroy and Mahafaly lands.[29]

Rainilaiarivony's first royal wife, Queen Rasoherina, died on 1 April 1868,[28] and was succeeded by her cousin Ranavalona II (crowned on 3 September 1868)[30] who, like Rasoherina, was a widow of Radama II. Ranavalona II was a pupil of Protestant missionaries and had converted to Christianity. Rainilaiarivony recognized the growing power of Christianity on the island and identified the need to bring it under his influence in order to avert destabilizing cultural and political power struggles. The Prime Minister encouraged the new queen to Christianize the court through a public baptism ceremony at Andohalo on 21 February 1869, the day of their marriage.[28] In this ceremony the supernatural royal talismans were ordered to be destroyed and replaced by the Bible. The Christianization of the court and the establishment of the independent royal Protestant chapel on the palace grounds prompted the wide-scale conversion of hundreds of thousands of Malagasy. These conversions were commonly motivated by a desire to express political allegiance to the Crown, and as such were largely nominal, with the majority of converts practicing a syncretic blend of Christian and traditional religions.[31] Rainilaiarivony's biographers conclude that the Prime Minister's own conversion was also largely a political gesture and most likely did not denote a genuine spiritual shift until late in his life, if ever.[32] Some local officials attempted to force conversions to Protestantism by mandating church attendance and persecuting Catholics, but Rainilaiarivony quickly responded to quell these overzealous practices. The Prime Minister's criminalization of polygamy and alcohol consumption, as well as the declaration of Sunday as a day of rest, were likewise inspired by the growing British and Protestant influences in the country.[28] The Christianization of the court came at a steep personal price: with the outlawing of polygamy, Rainilaiarivony was forced to repudiate his first wife.[30] The Prime Minister was deeply saddened by this necessity and by the consequent souring of his relationships with Rasoanalina and their children after the divorce.[33]

The Prime Minister recognized that the modernization of Madagascar and its system of state administration could strengthen the country against invasion by a Western power and directed his energy to this end. In 1877, he outlawed the enslavement of the Makoa community. Rainilaiarivony expanded the public education system, declaring school attendance mandatory in 1881 and forming a cadre of school inspectors the following year to ensure education quality. The island's first pharmacy was established by LMS missionaries in 1862, and the first hospital was inaugurated in Antananarivo three years later, followed by the launching in 1875 of a state medical system staffed by civil servant clinicians.[34] Rainilaiarivony enacted a series of new legal codes over the course of his administration that sought to create a more humane social order. The number of capital offenses was reduced from eighteen to thirteen, and he put an end to the tradition of collective family punishment for the crimes of one individual.[27] Fines were fixed for specific offenses and corporal punishment was limited to being locked in irons.[35] The structure of legal administration was reorganized so that matters that exceeded the authority of the traditional community courts at the level of the fokonolona village collective, administered by local magistrates and village heads, would be referred to the three high courts established in the capital in 1876, although final judicial authority remained with Rainilaiarivony. The Code of 305 Laws established that same year would form the basis of the legal system applied in Madagascar for the remainder of the 19th century and throughout much of the colonial period.[27] To strengthen rule of law, the Prime Minister introduced a rural police force, modernized the court system and eliminated certain unjust privileges that had disproportionately benefited the noble class.[28]

Beginning in 1872, Rainilaiarivony worked to modernize the army with the assistance of a British military instructor, who was hired to recruit, train and manage its soldiers.[27] Rainilaiarivony purchased new local and imported firearms, reintroduced regular exercises and reorganized the ranking system.[28] He prohibited the purchasing of rank promotions or exemptions from military service and instituted free medical care for soldiers in 1876. The following year Rainilaiarivony introduced the mandatory conscription of 5,000 Malagasy from each of the island's six provinces to serve five years in the royal army, swelling its ranks to over 30,000 soldiers.[36]

Foreign relations

During his time in power, Rainilaiarivony proved himself a competent and temperate leader, administrator and diplomat.[37] In foreign affairs he exercised acumen and prudent diplomacy, successfully forestalling French colonial designs upon Madagascar for nearly three decades. Rainilaiarivony established embassies in Mauritius, France and Britain, while treaties of friendship and trade were concluded with Britain and France in 1862 and revised in 1865 and 1868 respectively. Upon the arrival of the first American plenipotentiary in Antananarivo, a treaty between the United States and Madagascar was agreed in 1867.[38] A British contemporary observed that his diplomatic communication skills were particularly evident in his political speeches, describing Rainilaiarivony as a "Great orator among a nation of orators".[39]

The early years of Rainilaiarivony's tenure as Prime Minister saw a reduction in French influence on the island, to the benefit of the British, whose alliance he strongly preferred. Contributing factors to the eclipse of French presence included a military defeat in 1870 and economic constraints that forced an end to French government subsidy of Catholic missions in Madagascar in 1871. He permitted foreigners to lease Malagasy land for 99 years but forbade its sale to non-citizens. The decision not to undertake the construction of roads connecting coastal towns to the capital was adopted as a deliberate strategy to protect Antananarivo from potential invasion by foreign armies.[28]

Despite the strong presence of British missionaries, military advisers and diplomats in Antananarivo in the early part of Rainilaiarivony's administration, the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal led the British to shift their focus to reducing French presence in Egypt, at the expense of their own long-standing interests in Madagascar. When Jean Laborde died in 1878 and Rainilaiarivony refused to allow his heirs to inherit Malagasy land accorded him under Radama II's Lambert Charter, France had a pretext for invasion. Rainilaiarivony sent a diplomatic mission to England and France to negotiate release of their claims on Malagasy lands and was successful in brokering a new agreement with the British. Talks with the French conducted between November 1881 and August 1882 broke down without reaching consensus on the status of French land claims.[40] Consequently, France launched the First Franco-Hova War in 1883 and occupied the coastal port towns of Mahajanga, Antsiranana, Toamasina and Vohemar. Queen Ranavalona II died during the height of these hostilities in July 1883. Rainilaiarivony chose her 22-year-old niece, Princess Razafindrahety, to replace her under the throne name Ranavalona III. It was widely rumored that Rainilaiarivony may have ordered the poisoning of Razafindrahety's first husband in order to free the princess to become his spouse and queen.[41] Thirty-three years younger than her new husband, Ranavalona III was relegated to a largely ceremonial role during her reign, while the Prime Minister continued to manage the critical affairs of state.[42] In December 1885, Rainilaiarivony successfully negotiated the cessation of hostilities in the first Franco-Hova War.[28]

The agreement drafted between the French and Malagasy governments did not clearly establish a French protectorate over the island, partly because recent French military setbacks in the Tonkin Campaign had begun to turn popular opinion against French colonial expansion.[28] The Malagasy crown agreed to pay ten million francs to France to settle the dispute, a sum that was partly raised through the unpopular decision to increase fanampoana (forced labor in lieu of cash taxes) to mobilize the populace in panning for gold in the kingdom's rivers.[43] This expense, coupled with Rainilaiarivony's removal of $50,000 in silver and gold coins from the tomb of Ranavalona I to offset the cost of purchasing arms in the run-up to the First Franco-Hova War, effectively emptied the royal treasury reserves.[44] Capitalizing on Madagascar's weakened position, the French government then occupied the port town of Antsiranana and installed French Resident-General Le Myre de Vilers in Antananarivo, citing vague sections of the treaty as justification. The Resident-General was empowered by the French government to control international trade and foreign affairs on the island, although the monarchy's authority over internal administration was left unchallenged.[28] Refusing to acknowledge the validity of the French interpretation of the treaty, Rainilaiarivony continued managing trade and international relations and unsuccessfully solicited assistance from the United States in maintaining the island's sovereignty. In 1894, the French government pressed Rainilaiarivony to unconditionally accept the status of Madagascar as a French protectorate. In response, Rainilaiarivony broke off all diplomatic relations with France in November 1894.[45]

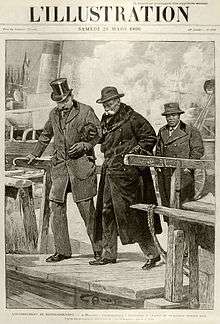

Deposition and exile

The cessation of diplomatic relations between France and Madagascar prompted immediate French military action in a campaign that became known as the Second Franco-Hova War.[45] The expedition ended eleven months later in September 1895 when a French military column reached Antananarivo and bombarded the royal palace with heavy artillery, blasting a hole through the roof of the queen's quarters and inflicting heavy casualties among the numerous courtiers gathered in the palace courtyard. Rainilaiarivony sent an interpreter to carry a white flag to the French commander and entreat his clemency. Forty-five minutes later he was joined by Radilifera, the Prime Minister's son, to request the conditions of surrender; these were immediately accepted. The following day Queen Ranavalona signed a treaty accepting the French protectorate over Madagascar. She and her court were permitted to remain at the palace and administer the country according to French dictates.[46]

Upon the queen's signing of the treaty, the French government deposed Rainilaiarivony from his position as Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief. The Minister of Foreign Affairs, an elderly man named Rainitsimbazafy, was jointly selected by the French and Ranavalona as his replacement. The French ordered Rainilaiarivony to be exiled to French Algeria, although he initially remained in Antananarivo for several months after the treaty was signed. On 15 October 1895 the former prime minister was placed under house arrest and put under the guard of Senegalese soldiers at his home in Amboditsiry. On 6 February 1896, at the age of 68, Rainilaiarivony boarded a ship bound for Algiers and left his island for the first time in his life. He was accompanied by his grandson, Ratelifera, as well as an interpreter and four servants. On 17 March 1896 the ship docked at the port of Algiers, where he would live out the few remaining months of his life.[46]

The French government installed Rainilaiarivony in the Geryville neighborhood of Algiers, one of the derelict parts of town. He was assigned a French attendant and guard named Joseph Vassé, who maintained detailed documentation on the personality and activities of Rainilaiarivony throughout his exile in French Algeria. Vassé described the former prime minister as a man of great spontaneity, sincere friendliness, and openness of heart, but also prone to mood swings, touchiness, and a tendency to be demanding, especially in regard to his particular tastes in clothing. His intelligence, tact and leadership qualities won him the admiration of many who knew him, including Le Myre des Vilers, who referred to him as both an enemy and a friend. Upon learning of Rainilaiarivony's living situation in Algiers, Le Myre de Vilers privately lobbied the French government for better accommodation. Consequently, Vassé found a new home for the former Prime Minister at the elegant estate called Villa des Fleurs ("Villa of the Flowers") in the upscale Mustapha Supérieur neighborhood, neighboring the residence of the exiled former king of Annam.[46]

The beauty of his Villa des Fleurs home and the warm reception he received in French Algeria pleased Rainilaiarivony and contributed to a positive impression of his new life in Algiers. He quickly developed an excellent reputation among the local high society, who perceived him as a kind, intelligent, generous and charming figure. The Governor-General of French Algeria regularly invited him to diplomatic balls and social events where Rainilaiarivony danced with the enthusiasm and endurance of a much younger man. When not busy with diverse social engagements, Rainilaiarivony avidly read the newspaper and corresponded with contacts in Madagascar. As an insurrection in Madagascar emerged against French rule, the former prime minister wrote a letter published in a Malagasy newspaper on 5 July 1896 that condemned the participants as ungrateful for the benefits that contact with the French would bring to the island.[47] His last outing in Algiers was on 14 July 1896 to watch the Bastille Day fireworks show. As he walked through the streets to join other spectators in his party, he was greeted with cheers and calls of "Vive le Ministre!" ("Long live the Minister!") from admiring onlookers.[46]

Death

The intense heat at the outdoor Bastille Day event on 14 July exhausted the former prime minister, and that evening Rainilaiarivony developed a fever. He slept poorly, disturbed by a dream in which he saw the former queen Rasoherina stand beside his bed, saying, "In the name of your brother, Rainivoninahitriniony, be ready." One of Rainilaiarivony's servants reported the dream to Vassé, explaining it as a premonition that foretold Rainilaiarivony's impending death. The former prime minister remained in bed and rapidly weakened over the next several days as his fever worsened and he developed a headache. He was constantly attended by his closest friends and loved ones. Rainilaiarivony died in his sleep on 17 July 1896.[48]

Rainilaiarivony's body was initially interred within a stone tomb in Algiers.[49] In 1900, the former prime minister's remains were exhumed and transported to Madagascar, where they were interred in the family tomb constructed by Jean Laborde in the Isotry neighborhood of Antananarivo. French colonial governor General Gallieni and Rainilaiarivony's grandson both spoke at the funeral, which was heavily attended by French and Malagasy dignitaries.[50] In his eulogy, Gallieni expressed esteem for the former prime minister in the following terms: "Rainilaiarivony was worthy of leading you. In the years to come, will there be a monument erected in his memory? This should be an obligation for the Malagasy who will have the freedom to do so. France has now taken Madagascar, come what may, but it's a credit to Rainilaiarivony to have protected it the way he did."[51] Following the funeral a commemorative plaque was installed at Rainilaiarivony's family tomb, engraved with the words "Rainilairivony, ex Premier Ministre et Commandant en chef de Madagascar, Commandeur de la Légion d'honneur" ("former Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief of Madagascar, Commander of the Legion of Honor").[52]

Online resource

Honours

National honours

-

.gif) Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Royal Hawk.[53]

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Royal Hawk.[53] -

.gif) Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Radama II.[54]

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Radama II.[54] -

.gif) Collar of the Order of Merit.[55]

Collar of the Order of Merit.[55] -

.gif) Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Ranavalona.[56]

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Ranavalona.[56]

Foreign honours

-

Commander of the Order of the Legion of Honour (18/01/1887).[57]

Commander of the Order of the Legion of Honour (18/01/1887).[57]

Notes

- ↑ Montgomery-Massingberd 1980, p. 166.

- 1 2 Chapus & Mondain 1953, p. 9.

- ↑ Nativel 2005, p. 136.

- ↑ Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 10–11.

- 1 2 3 Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Chapus & Mondain 1953, p. 18.

- 1 2 Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 294–297.

- ↑ Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 301–306.

- 1 2 Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Brown 1995, p. 163.

- 1 2 Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 14–16.

- 1 2 Chapus & Mondain 1953, p. 22.

- 1 2 Oliver 1886, p. 87.

- ↑ Chapus & Mondain 1953, p. 24.

- ↑ Oliver 1886, p. 88.

- ↑ Stratton 1964, p. 204.

- ↑ Chapus & Mondain 1953, p. 39.

- 1 2 Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 42–46.

- ↑ Raison-Jourde 1983, pp. 358–359.

- 1 2 3 Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 48–54.

- ↑ Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Heseltine 1971, p. 120.

- 1 2 Deschamps 1994, p. 414.

- ↑ Nativel 2005, p. 139.

- ↑ Nativel 2005, pp. 139–158.

- ↑ Nativel 2005, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 4 Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 441.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Thompson & Adloff 1965, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Oliver, Fage & Sanderson 1985, p. 527.

- 1 2 Deschamps 1994, p. 413.

- ↑ Daughton 2006, p. 172.

- ↑ Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 91-93.

- ↑ Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 308–309.

- ↑ Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 439.

- ↑ Oliver, Fage & Sanderson 1985, p. 522.

- ↑ Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 442.

- ↑ Ade Ajayi 1998, pp. 439–446.

- ↑ Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 445.

- ↑ Oliver 1885, p. 234.

- ↑ Oliver, Fage & Sanderson 1985, p. 524.

- ↑ Ministère de la marine et des colonies 1884, p. 117.

- ↑ Cousins 1895, p. 73.

- ↑ Randrianja & Ellis 2009, p. 152.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, p. 298.

- 1 2 Thompson & Adloff 1965, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 4 Chapus & Mondain 1953, p. 377.

- ↑ Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 385–386.

- ↑ Chapus & Mondain 1953, pp. 387–389.

- ↑ Randrianja 2001, pp. 100–110.

- ↑ Nativel & Rajaonah 2009, p. 126.

- ↑ Randrianja 2001, p. 116.

- ↑ Nativel & Rajaonah 2009, p. 125.

- ↑ Royal Ark

- ↑ Royal Ark

- ↑ Royal Ark

- ↑ Royal Ark

- ↑ Royal Ark

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rainilaiarivony. |

- Ade Ajayi, J.F. (1998). General history of Africa: Africa in the nineteenth century until the 1880s. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-0-520-06701-1.

- Brown, M. (1995). A History of Madagascar. Cambridge, U.K.: Damien Tunnacliffe. ISBN 978-0-9506284-5-5.

- Campbell, Gwyn (2005). An economic history of Imperial Madagascar, 1750–1895: the rise and fall of an island empire. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83935-8.

- Chapus, G.S.; Mondain, G. (1953). Un homme d'etat malgache: Rainilaiarivony (in French). Paris: Editions Diloutremer.

- Cousins, William Edward (1895). Madagascar of to-day. London: The Religious Tract Society.

- Daughton, J.P. (2006). An Empire Divided: Religion, Republicanism, And the Making of French Colonialism, 1880–1914. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530530-2.

- Deschamps, H. (1994). "Tradition and change in Madagascar: 1790–1870". In Flint, J.E. From C. 1790 to C. 1870: Volume 5 of the Cambridge history of Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20701-0.

- Heseltine, N. (1971). Madagascar. New York: Praeger.

- Ministère de la marine et des colonies (1884). Revue maritime et coloniale, Volume 81 (in French). Paris: Gouvernement de la France.

- Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh (1980). Burke's Royal Families of the World: Africa & the Middle East. London: Burke's Peerage.

- Nativel, D. (2005). Maisons royales, demeures des grands à Madagascar (in French). Antananarivo, Madagascar: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-84586-539-6.

- Nativel, D.; Rajaonah, F. (2009). Madagascar revisitée: en voyage avec Françoise Raison-Jourde (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-8111-0174-9.

- Oliver, R.A.; Fage, J.D.; Sanderson, G.I. (1985). The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1870 to c. 1905. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22803-9.

- Oliver, S.P. (1885). The true story of the French dispute in Madagascar. London: British Library.

- Oliver, S.P. (1886). Madagascar: An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Island and its Former Dependencies, Volume 1. New York: Macmillan and Co.

- Raison-Jourde, Françoise (1983). Les souverains de Madagascar (in French). Antananarivo: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-86537-059-7.

- Randrianja, S. (2001). Société et luttes anticoloniales à Madagascar: de 1896 à 1946 (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-84586-136-7.

- Randrianja, S.; Ellis, S. (2009). Madagascar: A Short History. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-70418-0.

- Stratton, A. (1964). The Great Red Island. New York: Scribner.

- Thompson, V.; Adloff, R. (1965). The Malagasy Republic: Madagascar today. San Francisco, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0279-9.