Regicide

| Part of a series on |

| Homicide |

|---|

| Murder |

|

Note: Varies by jurisdiction

|

| Manslaughter |

| Non-criminal homicide |

|

Note: Varies by jurisdiction |

| By victim or victims |

| Family |

| Other |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Monarchy |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Central concepts |

|

History |

| Politics portal |

The broad definition of regicide (Latin regis "of king" + cida "killer" or cidium "killing") is the deliberate killing of a monarch, or the person responsible for the killing of a person of royalty. In a narrower sense, in the British tradition, it refers to the judicial execution of a king after a trial. More broadly, it can also refer to the killing of an emperor or any other reigning sovereign.

The regicide of Mary, Queen of Scots

Before the Tudor period, English kings had been murdered while imprisoned (for example Edward II or Edward V) or killed in battle by their subjects (for example Richard III), but none of these deaths are usually referred to as regicide. The word regicide seems to have come into popular use among foreign Catholics when Pope Sixtus V renewed the papal bull of excommunication against the "crowned regicide" Queen Elizabeth I,[1] for—among other things—executing Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1587. Elizabeth had originally been excommunicated by Pope Pius V, in Regnans in Excelsis, for converting England to Protestantism after the reign of Mary I of England. The defeat of the Spanish Armada and the "Protestant Wind" convinced most English people that God approved of Elizabeth's action.

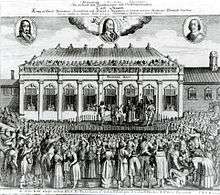

The regicide of Charles I of England

After the First English Civil War, King Charles I was a prisoner of the Parliamentarians. They tried to negotiate a compromise with him, but he stuck steadfastly to his view that he was King by Divine Right and attempted in secret to raise an army to fight against them. It became obvious to the leaders of the Parliamentarians that they could not negotiate a settlement with him and they could not trust him to refrain from raising an army against them; they reluctantly came to the conclusion that he would have to be put to death. On 13 December 1648, the House of Commons broke off negotiations with the King. Two days later, the Council of Officers of the New Model Army voted that the King be moved from the Isle of Wight, where he was prisoner, to Windsor "in order to the bringing of him speedily to justice".[2] In the middle of December, the King was moved from Windsor to London. The House of Commons of the Rump Parliament passed a Bill setting up a High Court of Justice in order to try Charles I for high treason in the name of the people of England. From a Royalist and post-restoration perspective this Bill was not lawful, since the House of Lords refused to pass it and it failed to receive Royal Assent. However, the Parliamentary leaders and the Army pressed on with the trial anyway.

At his trial in front of The High Court of Justice on Saturday 20 January 1649 in Westminster Hall, Charles asked "I would know by what power I am called hither. I would know by what authority, I mean lawful".[3] In view of the historic issues involved, both sides based themselves on surprisingly technical legal grounds. Charles did not dispute that Parliament as a whole did have some judicial powers, but he maintained that the House of Commons on its own could not try anybody, and so he refused to plead. At that time under English law if a prisoner refused to plead then this was treated as a plea of guilty (This has since been changed; a refusal to plead now is interpreted as a not-guilty plea).[4]

He was found guilty on Saturday 27 January 1649, and his death warrant was signed by 59 Commissioners. To show their agreement with the sentence of death, all of the Commissioners who were present rose to their feet.

On the day of his execution, 30 January 1649, Charles dressed in two shirts so that he would not shiver from the cold, in case it was said that he was shivering from fear. His execution was delayed by several hours so that the House of Commons could pass an emergency bill to make it an offence to proclaim a new King, and to declare the representatives of the people, the House of Commons, as the source of all just power. Charles was then escorted through the Banqueting House in the Palace of Whitehall to a scaffold where he would be beheaded.[5] He forgave those who had passed sentence on him and gave instructions to his enemies that they should learn to "know their duty to God, the King - that is, my successors - and the people".[6] He then gave a brief speech outlining his unchanged views of the relationship between the monarchy and the monarch's subjects, ending with the words "I am the martyr of the people".[7] His head was severed from his body with one blow.

One week later, the Rump, sitting in the House of Commons, passed a bill abolishing the monarchy. Ardent Royalists refused to accept it on the basis that there could never be a vacancy of the Crown. Others refused because, as the bill had not passed the House of Lords and did not have Royal Assent, it could not become an Act of Parliament.

The Declaration of Breda 11 years later paved the way for the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. At the restoration, thirty-one of the fifty-nine Commissioners who had signed the death warrant were living. A general pardon was given by Charles II and Parliament to his opponents, but the regicides were excluded. A number fled the country. Some, such as Daniel Blagrave, fled to continental Europe, while others like John Dixwell, Edward Whalley, and William Goffe fled to New Haven, Connecticut. Those who were still available were put on trial. Six regicides were found guilty and suffered the fate of being hanged, drawn and quartered: Thomas Harrison, John Jones, Adrian Scroope, John Carew, Thomas Scot, and Gregory Clement. The captain of the guard at the trial, Daniel Axtell who encouraged his men to barrack the King when he tried to speak in his own defence, an influential preacher Hugh Peters, and the leading prosecutor at the trial John Cook were executed in a similar manner. Colonel Francis Hacker who signed the order to the executioner of the king and commanded the guard around the scaffold and at the trial was hanged. Concern amongst the royal ministers over the negative impact on popular sentiment of these public tortures and executions led to jail sentences being substituted for the remaining regicides.[8]

Some regicides, such as Richard Ingoldsby were pardoned, while a further nineteen served life imprisonment. The bodies of the regicides Cromwell, Bradshaw and Ireton which had been buried in Westminster Abbey were disinterred and hanged, drawn and quartered in posthumous executions. In 1662, three more regicides John Okey, John Barkstead and Miles Corbet were also hanged, drawn and quartered. The officers of the court that tried Charles I, those who prosecuted him and those who signed his death warrant, have been known ever since the restoration as regicides.

The Parliamentary Archives in the Palace of Westminster, London, holds the original death warrant of Charles I.

Other regicides

Under the definition of a regicide in common usage in England, there have been two other such events since 1649: the execution of Louis XVI of France in 1793, after sentence of death by the National Convention and Maximilian I of Mexico in 1867 by a Mexican court-martial. Pope Sixtus V gave a broader definition of regicide. According to his definition, excluding monarchs killed in battle, other regicides include:

- 1962 BC Amenemhat I, of Egypt by his own bodyguards

- 1526 BC Mursili I, King of the Hittites by his brother-in-law Hantili I

- unknown date in late 2nd millennium BC, Eglon of Moab by Ehud

- 1155 BC Ramesses III of Egypt from a neck wound inflicted by conspirators

- 11th century BC Agag of Amalek by the prophet Samuel

- 1005 BC Ish-bosheth of Israel, slain by his own captains

- 900 BC Nadab of Israel, slain by own captain Baasha

- 885 BC King Elah of Israel, murdered by his chariot commander Zimri

- 841 BC Jehoram of Israel, murdered by Jehu

- 836 BC Athaliah, Queen of Judah, by rebels that placed Jehoash on the throne

- 797 BC Jehoash of Judah by his own servants at Miloh

- 771 BC King You of Zhou by the Marquess of Shen

- 767 BC Amaziah of Judah assassinated at Lachish

- 752 BC Zechariah of Israel murdered by Shallum

- 740 or 737 BC Pekahiah, King of Israel, assassinated by Pekah, son of Remaliah

- 732 BC Pekah, King of Israel, by Hoshea

- 681 BC Sennacherib, King of Assyria, assassinated in obscure circumstances

- 641 BC Amon of Judah, assassinated by own servants

- 465 BC Xerxes I of Persia by his chief bodyguard Artabanus

- 424 BC Xerxes II of Persia by his brother Sogdianus

- 336 BC Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great in unclear circumstances

- 207 BC Qin Er Shi through forced suicide put on him by his eunuch Zhao Gao

- 206 BC Ziying executed by Xiang Yu

- 185 BC Brihadratha Maurya of India, assassinated by Pushyamitra Shunga during a military parade

- 104 BC Jugurtha, King of Numidia, captured by Roman army, paraded in Rome and starved to death in prison

- 25 AD the Gengshi Emperor by strangulation from Xie Lu

- 41 Caligula by a group of conspirators supported by the Roman senate

- 69 Galba by the praetorian guard

- 69 Vitellius by Vespasian's troops

- 96 Domitian by a group of court officials

- 190 Emperor Shao of Han forced to drink poison by rebels

- 192 Commodus strangled by his wrestling partner supported by a group of conspirators

- 193 Pertinax murdered by Praetorian guard

- 193 Didius Julianus executed on orders by the senate

- 217 Caracalla murdered by a conspiracy

- 218 Macrinus, executed by Elagabalus

- 222 Elagabalus murdered by Praetorian guard

- 235 Severus Alexander murdered by the army

- 238 Maximinus I murdered by Praetorian guard

- 238 Pupienus murdered by Praetorian guard

- 238 Balbinus murdered by Praetorian guard

- 253 Trebonianus Gallus by his own troops

- 253 Aemilian by his own troops

- 268 Gallienus murdered by his own commanders

- 275 Aurelian assassinated by Praetorian guard

- 276 Florianus assassinated by his own troops

- 282 Marcus Aurelius Probus assassinated by his own troops

- 307 Severus II forced to commit suicide by Maxentius

- 310 Maximian forced to commit suicide by Constantine I

- 325 Licinius executed on orders by Constantine I

- 350 Constans killed by supporters of Magnentius

- 359 Gratian murdered by army faction

- 423 Joannes captured and executed by eastern Roman army

- 453 Emperor Wen of Liu Song by Crown Prince Liu Shao

- 455 Valentinian III assassinated

- 456 Emperor Ankō of Japan, by Prince Mayowa

- 565 Diarmait mac Cerbaill, King of Tara, by Áed Dub mac Suibni

- 592 Emperor Sushun of Japan, by Soga no Umako

- 618 Emperor Yang of Sui, strangled by soldier in coup

- 656 Uthman ibn Affan, Sunni Caliph, assassinated by rebels

- 710 Emperor Zhongzong of Tang poisoned by his wife Empress Wei

- 904 Emperor Zhaozong of Tang by soldiers sent by Zhu Quanzhong

- 908 Emperor Ai of Tang poisoned on orders by Zhu Quanzhong

- 1072 Sancho II of Castile and León assassinated by Vellido Dolfos

- 1192 Conrad of Montferrat, King of Jerusalem, assassins unknown to history

- 1199 Richard I of England shot with crossbow by Pierre Basile

- 1206 Muhammad of Ghor, Sultan of the Ghurid Empire, assassinated while doing evening prayers

- 1296 Przemysł II, King of Poland, by the Margraves of Brandenburg, some Polish families, or maybe both

- 1323 Emperor Gong of Song, forced to commit suicide by Emperor Yingzong of Yuan

- 1323 Emperor Yingzong of Yuan by a plot formed among Yesün Temür's supporters

- 1359 Berdi Beg of the Golden Horde by his brother Qulpa

- 1402 the Jianwen Emperor was claimed to have been burned to death in his palace by Zhu Di

- 1483 Edward V of England by either Richard III or some other party

- 1520 Moctezuma II, Emperor of the Aztecs, by either the Spanish or his own people

- 1532 Huáscar, Emperor of the Incas, executed by his brother Atahualpa

- 1533 Atahualpa, Emperor of the Incas, executed by the Spanish

- 1589 Henry III of France by Jacques Clément

One of the assistants of Sanson shows the head of Louis XVI.

One of the assistants of Sanson shows the head of Louis XVI. - 1610 Henry IV of France by François Ravaillac

- 1622 Osman II of the Ottoman Empire by the Grand Vizier Davud Pasha

- 1747 Nader Shah of the Afshar Dynasty, Shahanshah of Persia (Iran) by Salah Bey

- 1762 Peter III of Russia deposed and supposedly murdered shortly thereafter

- 1782 Taksin, King of Thailand, deposed and executed in a coup

- 1792 Gustav III of Sweden by Jacob Johan Anckarström

- 1801 Emperor Paul of Russia by Count Pahlen and his accomplices

- 1828 Shaka King of the Zulus by his half-brother and successor Dingane and accomplices

- 1881 Alexander II of Russia by Ignacy Hryniewiecki, a member of Narodnaya Volya (People's Will)

- 1895 Min of Joseon by three mercenary killers allegedly hired by Japanese minister to Korea Miura Goro

- 1896 Nasser al-Din Shah, Qajar king of Persia (Iran), by Mirza Reza Kermani.

- 1898 Empress Elisabeth of Austria by Luigi Lucheni, an anarchist in Geneva.

- 1900 Umberto I of Italy by anarchist Gaetano Bresci.

- 1903 Alexander I of Serbia and his wife Queen Draga by a group of army officers.

- 1908 Carlos I of Portugal, assassinated with his son Luís Filipe by Alfredo Costa and Manuel Buiça, both connected to the Carbonária (the Portuguese section of the Carbonari)

- 1908 the Guangxu Emperor by arsenic poisoning, perhaps on orders from Yuan Shikai

- 1913 George I of Greece by Alexandros Schinas

- 1918 Nicholas II of Russia and the Imperial Family executed by a Bolshevik firing squad under the command of Yakov Yurovsky

- 1933 Mohammed Nadir Shah, king of Afghanistan, assassinated by student Abdul Khaliq Hazara

- 1934 Alexander I of Yugoslavia by Vlado Chernozemski, a member of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization

- 1943 Boris III, king of Bulgaria, poisoned by Nazi agents on orders of Adolf Hitler for opposing Hitler's insistence that Boris deport Bulgarian Jews to Nazi death camps, and for opposing Nazi Germany's invasion of the USSR

- 1946 Ananda Mahidol of Thailand. The King's death is still a mystery and may have been either regicide or suicide. The subject is never openly discussed in Thailand.

- 1948 Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din, king of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen, assassinated in the Alwaziri coup

- 1951 Abdullah I of Jordan by Mustafa Ashi

- 1958 Faisal II of Iraq executed by firing squad under the command of Captain Abdus Sattar As Sab, a member of the coup d'état led by Colonel Abdul Karim Qassim.

- 1975 Faisal of Saudi Arabia by his nephew Faisal bin Musa'id (Assassin publicly beheaded)

- 2001 Birendra of Nepal by his son Crown Prince Dipendra in the massacre of the Nepalese royal family; Dipendra proceeded to commit suicide without having been crowned king.

Regicides as murders

Regicide has particular resonance within the concept of the divine right of kings, whereby monarchs were presumed by decision of God to have a divinely anointed authority to rule. As such, an attack on a king by one of his own subjects was taken to amount to a direct challenge to the monarch, to his divine right to rule, and thus to God's will.

In the bible, David refuses to harm King Saul, because he is the Lord's anointed, even when Saul is seeking his life. And when Saul eventually is killed in battle and a person comes to David to tell him that he helped kill Saul, David puts the man to death, even though Saul had been his enemy, because he had raised his hands against the Lord's anointed. Christian concepts of the inviolability of the person of the monarch have great influence from this story. Diarmait mac Cerbaill, King of Tara (mentioned above), was killed by Áed Dub mac Suibni in 565. According to Adomnan of Iona's Life of St Columba, Áed Dub mac Suibni received God's punishment for this crime by being impaled by a treacherous spear many years later and then falling from his ship into a lake and drowning.[9]

Even after the disappearance of the divine right of kings and the appearance of constitutional monarchies, the term continued and continues to be used to describe the murder of a king.

In France, the judicial penalty for regicides (i.e. those who had murdered, or attempted to murder, the king) was especially hard, even in regard to the harsh judicial practices of pre-revolutionary France. As with many criminals, the regicide was tortured so as to make him tell the names of his accomplices. However, the method of execution itself was a form of torture. Here is a description of the death of Robert-François Damiens, who attempted to kill Louis XV:

He was first tortured with red-hot pincers; his hand, holding the knife used in the attempted murder, was burnt using sulphur; molten wax, lead, and boiling oil were poured into his wounds. Horses were then harnessed to his arms and legs for his dismemberment. Damiens' joints would not break; after some hours, representatives of the Parlement ordered the executioner and his aides to cut Damiens' joints. Damiens was then dismembered, to the applause of the crowd. His trunk, apparently still living, was then burnt at the stake.

In Discipline and Punish, the French philosopher Michel Foucault cites this case of Damiens the Regicide as an example of disproportionate punishment in the era preceding the "Age of Reason". The classical school of criminology asserts that the punishment "should fit the crime", and should thus be proportionate and not extreme. This approach was spoofed by Gilbert and Sullivan, when The Mikado sang, "My object all sublime, I shall achieve in time, to let the punishment fit the crime".[10]

In common with earlier executions for regicides:

- the hand that attempted the murder is burnt

- the regicide is dismembered alive

In both the François Ravaillac and the Damiens cases, court papers refer to the offenders as a patricide, rather than as regicide, which lets one deduce that, through divine right, the king was also regarded as "Father of the country".

Regicide in literature and fiction

The Tragedy of Macbeth (commonly called Macbeth) by William Shakespeare is about a man who commits regicide so as to become king and then commits further murders to maintain his power.

The Greek tragedy Oedipus the King is a tragedy by Sophocles about King Oedipus who vows to find the murderer of his father Laius. He is unaware that he himself is the murderer. Early in the play, Oedipus encountered Laius on the road to Thebes. Unaware of each other's identities, they quarrel over whose chariot has right-of-way. King Laius moves to strike the insolent youth with his scepter, but Oedipus throws him down from the chariot and kills him.

Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur canonizes King Arthur's murder at the hands of Sir Mordred during the Battle of Camlann. Sir Mordred, who in some traditions is Arthur's son or nephew, delivers a mortal wound to Arthur while he himself receives a fatal blow. In some traditions, Mordred also attempts to take Arthur's wife, Queen Guinevere, as his own queen.

The American novel series A Song of Ice and Fire and its TV adaptation, from George R. R. Martin, has in the main cast a character named Jaime Lannister, a member of the Kingsguard who murdered the king, Aerys II Targaryen, often called the "Mad King" to prevent him from destroying the capital city as rebel forces, led by Jaime's lord father, Lord Tywin Lannister, stormed the city. Jaime Lannister was later absolved of his crime by the rebel king but was condemned as the "Kingslayer".

The 2013 TV series Reign created by Stephanie SenGupta and Laurie McCarthy has a major plot about regicide. The new King Francis was blackmailed by one of his Lords with evidence that King Francis killed his own father which is regicide. Even the King himself could be charged with regicide and beheaded.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Regicides. |

- Fifth Monarchists saw the overthrow of Charles I as a divine sign of the second coming of Jesus.

- Society of King Charles the Martyr

- Tyrannicide (killing of a tyrant)

- Patricide (killing of one's father)

- Matricide (killing one's mother)

- Fratricide (killing one's brother)

- Sororicide (killing one's sister)

References

- "The opening speech of Charles I at his trial". The Constitution Society. Archived from the original on 2012-05-10. Retrieved May 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Kirby, Michael (22 January 1999). The trial of King Charles I – defining moment for our constitutional liberties (PDF). Anglo-Australian Lawyers' Association, London. Canberra: High Court of Australia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-02-12.

- Da Magliano, Pamfilo, ed. (1867), The life of Saint Francis of Assisi: and a sketch of the Franciscan order (American ed.), New York: P. O'Shea, OCLC 655576151

- Wedgewood, Cicely V. (2001) [1964]. A Coffin for King Charles: The Trial of Charles I. Pleasantville, NY: Akadine Press. ISBN 1-58579-033-8.

Further reading

- David Lagomarsino, Charles T. Wood (Editor) The Trial of Charles I: A Documentary History Pub: Dartmouth College, (November 1989), ISBN 0-87451-499-1

- Geoffrey Robertson The Tyrannicide Brief, Pub: Random House, (August 2005), ISBN 0-7011-7602-4

- Act abolishing the Office of King, 17 March, 1649

Footnotes

- ↑ Da Magliano 1867, p. 631

- ↑ Kirby 1999, p. 8 footnote 9, cites: Wedgewood 1964, p. 44

- ↑ Kirby 1999, pp. 10,13 footnotes 12 and 17. "The record of the Trial also appears in Cobbett's Complete Collection of State Trials, Vol IV, covering 1640-1649 published in London in 1809. p. 995".

- ↑ Kirby 1999, p. 14.

- ↑ Pestana, Carla Gardina (2004). The English Atlantic in an Age of Revolution, 1640-1661. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: Harvard University Press. p. 88.

- ↑ Kirby 1999, p. 21 § "After the trial" ¶ 4

- ↑ Kirby 1999, p. 21 footnotes 12 and 35. "The record of the Trial also appears in Cobbett's Complete Collection of State Trials, Vol IV, covering 1640-1649 published in London in 1809. p. 1132."

- ↑ page 19 "History Today", February 2014

- ↑ Adomnan of Iona. Life of St Columba. Penguin books, 1995

- ↑ http://math.boisestate.edu/gas/mikado/webopera/mk206.html

External links

-

Works related to a survey of regicides in the 19th century. at Wikisource

Works related to a survey of regicides in the 19th century. at Wikisource -

The dictionary definition of regicide at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of regicide at Wiktionary