Empire of Japan–Russian Empire relations

|

|

Russia |

Japan |

|---|---|

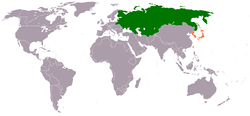

The Relations between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire were minimal until 1855, mostly friendly from 1855 to the early 1890s, then turned hostile over the status of Korea. Diplomatic and commercial relations between the two empires were established from 1855 onwards. The Russian Empire officially ended in 1917, and was succeeded by Communist rule formalized in 1922 by the Soviet Union.

For later periods, see Japan–Soviet Union relations (1917–1991) and the Japan–Russia relations (1992–present).

Establishment of relations (1778–1860)

From the beginning of the 17th century, the Tokugawa shogunate which ruled Japan imposed a state of isolation, forbidding trade and contact with the outside world, with the two exception exceptions of China and the Netherlands, which was strongly restricted. The Netherlands was only allowed to trade from the artificial island of Deshima in the port of Nagasaki. Entering Japan itself was strictly prohibited.

From the early 19th century, the western colonial powers especially Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Russia, were expanding politically and economically into new markets, and were seeking to impose hegemony over much of Asia. Japan was important due to its strategic location in the Pacific Ocean off of the China coast, with a large and untapped economic potential.

As neighbors, Japan and Russia had early interactions, usually disputes over fishing grounds and territorial claims. Various documents speak of the capture of Japanese fishermen on the Kamchatka Peninsula. Some of these Japanese captives were taken over the Siberian route to Saint Petersburg, where they were used in the education of Japanese language and culture.

18th century contacts

Pavel Lebedev-Lastochkin (1778–79)

In 1778, Pavel Lebedev-Lastochkin, a merchant from Yakutsk, arrived in Hokkaidō with a small expedition. He was told to come back the following year. In 1779, he entered the harbour of Akkeshi, he offered gifts, and asked to trade, but was told by government officials that, per long establish policy, foreign trade would be only permitted in Nagasaki.

Adam Laxman (1792)

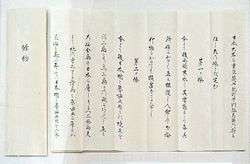

A second Russian-Japanese interaction took place in 1792. A Russian naval officer named Adam Laxman (alternately spelled as Adam Laksman) arrived in Hokkaidō. First in the town of Matsumae and later Hakodate, he attempted to establish a Russian trade agreement with Japan in order to break the exclusive trade rights of the Dutch. The Japanese suggested that Laxman leave, but Laxman had one demand: he would only leave with a trade-agreement for Russia. After a long time and annoyed by the stubborn Laxman, the Japanese finally handed over a document stipulating Russia's right to send one Russian vessel of commerce to the harbor of Nagasaki. Secondly, it also restricted Russian commerce to Nagasaki. Trade elsewhere in Japan was prohibited. A final note in the document clearly stated that the practice of Christianity inside Japan was prohibited. Laxman returned to Russia.[1] Eventually, the Russians sent their vessel of commerce to Nagasaki, but they were not allowed to enter the harbor. The document was of no value.

Rezanov

Tsar Alexander I of Russia had started a worldwide Russian representation mission under the lead of Adam Johann von Krusenstern (Russian: Крузенштерн). With Japan in mind, Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov was appointed to the mission. He was the founder of Russian–Siberian trade in fur and the ideal man to convince the Japanese.

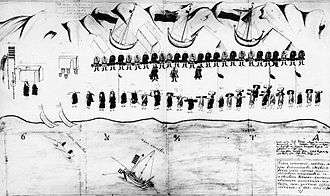

In 1804, Rezanov got a chance to exercise his diplomatic strength in Japan. On board the ship Nadezhda, he had many gifts for the Shogunate and even brought along Japanese fishermen who had been stranded in Russia. But Rezanov could not do what so many had tried before him. An agreement was never reached. During the negotiations, the Shogun remained silent for months; next, the Shogun refused any negotiations and finally gave the Russian gifts back. Now Russia acted more assertively, and soon Russian navigators started to explore and map the coasts of the Kuril Islands. In 1811, the Russian colonel Vasily Golovnin was exploring Kunashir Island on behalf of the Russian Academy of Sciences. During these operations the Russians clashed with the Japanese. Golovnin was seized and taken prisoner by samurai. For the following 18 months, he remained a prisoner in Japan, where officials of the Tokugawa Shogun questioned him about Russian language and culture, the state of the European power struggles, and European scientific and technical developments. Golovnin's memoirs (Memoirs of Captivity in Japan During the Years 1811, 1812, and 1813) illustrate some of the methods used by Tokugawa officials.

Later on, these unsuccessful attacks would be disavowed by Russia and its interest in Japan would drop for a full generation. This would be the case until the First Opium War in 1839. The Russian Tsar Nicholas I realised the territorial expansion of Great Britain in Asia and the expansion of the United States in the Pacific Ocean and northern America. As a result, he founded a committee in 1842 to investigate Russia's power in areas around the Amur River and in Sakhalin. The committee proposed a mission to the area under the lead of Admiral Yevfimy Putyatin. The plan was not approved because officials expressed concerns it would disrupt the Kyakhta trade, and many did not believe Russia had great commercial assets to be defended in these cold and desolate places. The highly esteemed China was surprisingly (in the eyes of the Japanese) beaten by Great Britain in the Opium Wars. Although Japan was in isolation from the outside world, it was not blind to European capabilities and dangers. In light of these events, Japan began modernization of its military and coastal defenses.

Yevfimy Putyatin

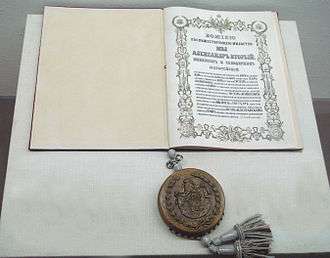

In 1852, on learning of American plans to send Commodore Matthew Perry in an attempt to open Japan for foreign trade, the Russian government revived Putyatin’s proposal, which received support from Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich of Russia. The expedition included several notable Sinologists and a number of scientists and engineers, as well as the noted author Ivan Goncharov, and the Pallada under the command of Ivan Unkovsky was selected as the flagship. After many mishaps, Putyatin signed three treaties between 1855 and 1858 by which Russia established diplomatic and commercial relations with Japan. (see Treaty of Shimoda)

Deteriorating relations and war (1860–1914)

Three changes took place during the second half of the 19th century, which caused a gradual shift to hostility in the relations between the two countries. Firstly, while Russia had expanded to the shores of the Pacific since 1639, their position in the region had remained weak. This changed from 1860 onwards, as the Russian Empire by the Treaty of Peking acquired from China a long strip of Pacific coastline south of the mouth of the Amur River and began to build the naval base of Vladivostok. As Vladivostok was not an ice-free port, the Russian Empire was still striving to obtain a more southern port. In 1861, Russia attempted to seize the island of Tsushima from Japan and to establish an anchorage, but failed largely due to political pressure from Great Britain and other western powers.

Secondly, Japan became an emerging industrial and military power since the end of its self-imposed isolation in 1854. Thirdly, China became increasingly internally weak. Due to these changes, competition between the two empires for Chinese territory arose.

Treaty of Saint Petersburg

In 1875, the Treaty of Saint Petersburg gave Russia territorial control over all of Sakhalin and gave Japan control over all the Kuril Islands. Japan hoped to prevent Russian expansionism in Japanese territories by clearly delineating the border between the two empires.

The First Sino-Japanese War

Japan defeated China in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95). After this war Russia faced the choice of collaborating with Japan (with which relations had been fairly good for some years) at the expense of China or assuming the role of protector of China against Japan. Russia chose the second policy, largely under the influence of foreign minister Count Sergei Witte. Russia as one of the three European powers of the Triple Intervention (France and Germany were the other two) pressured Japan to give up some of its territorial gains from that war. Japan eventually ceded the Liaotung Peninsula and Port Arthur (both territories were located in south-eastern Manchuria, a Chinese province) back to China.

Much to Japan's astonishment and consternation, Russia then concluded an alliance with China (in 1896 by the Li–Lobanov Treaty), which led in 1898 to an occupation and administration (by Russian personnel and police) of the entire Liaodong Peninsula and to a fortification of the ice-free Port Arthur. Russia also established the Russian-owned Chinese Eastern Railway, which was to cross northern Manchuria from west to east, linking Siberia with Vladivostok. Germany, France and even Great Britain also took advantage of the weakened China to seize port cities on various pretexts, and to expand their spheres of influence. When in 1899 the Boxer Rebellion broke out and the European powers sent armed forces to relieve their diplomatic missions in Peking, the Russian government used this as an opportunity to bring a substantial army into Manchuria. As a consequence, Manchuria became a fully incorporated outpost of the Russian Empire in 1900.

Japanese containment of Russia

In 1902 Japan and the British Empire forged the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, which would last until 1923. The purpose of this alliance was to contain the Russian Empire in East Asia. In response to this alliance, Russia formed a similar alliance with France and began to renege on agreements to reduce troop strength in Manchuria. From Russian perspective, it seemed inconceivable that Japan, a non-European power which was considered to be undeveloped (i.e. not-industrial), and almost bereft of natural resources, would challenge the Russian Empire. This view would change when Japan started and won the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05).

In 1905 both sides accepted the offer of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt to mediate a peace treaty; the parties met in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The war was ended by the Treaty of Portsmouth as both sides agreed to evacuate Manchuria and return its sovereignty to China. However Japan leased the Liaodong Peninsula (containing Port Arthur and Talien) and the Russian-built South Manchurian Railway in southern Manchuria with access to strategic resources. Japan also received the southern half of the Island of Sakhalin from Russia. Japan dropped its demand for an indemnity. Roosevelt won the Nobel Peace Prize for his successful efforts. Historian George E. Mowry concludes that Roosevelt handled the arbitration well, doing an "excellent job of balancing Russian and Japanese power in the Orient, where the supremacy of either constituted a threat to growing America."[2][3]

The alliance with Britain had served Japan greatly by discouraging France, Russia's European ally, from intervening in the war as this would mean war with Great Britain. (If France had intervened, it would have been the second hostile Power,and, as such, would have triggered Article 3 of the Treaty.) The alliance was renewed and strengthened in 1905 and 1911. The treaty expired in 1921 and was officially terminated in 1923.

World War I (1914–1917)

The alliance with Britain prompted Japan to enter World War I on the British (and thus Russian) side. Since Japan and Russia had become allies by convenience, Japan sold back to Russia a number of former Russian ships, which Japan had captured during the Russo-Japanese War.

For 1917–1991, see Japan–Soviet Union relations.

Notes

- ↑ A. A. Preobrazhensky, “Pervoe Russkoe Posol'stvo v Yaponiyu” (“The first Russian mission to Japan”)

- ↑ George E. Mowry, "The First Roosevelt," The American Mercury, (November 1946) quote at p. 580 online

- ↑ Eugene P. Trani, The Treaty of Portsmouth: An Adventure in American Diplomacy (1969).

Further reading

- Akagi, Roy Hidemichi. Japan's Foreign Relations 1542–1936: A Short History (1979)

- Beasley, William G. Japanese Imperialism, 1894–1945 (1987)

- Langer, William A. The Diplomacy of Imperialism, 1890–1902 (2nd ed 1950) ch. 12, 14, 23

- Lensen, George A. The Russian Push Toward Japan: Russo-Japanese Relations, 1697–1875 (2011)

- Matsusaka, Yoshihisa Tak. The Making of Japanese Manchuria, 1904–1932 (2003)

See also

Russia

- Russian history, 1855–1892

- Russian history, 1892–1917

- Sino-Russian relations

- Russia–United States relations

Japan

- Sakoku

- Japan–United Kingdom relations

- People's Republic of China–Japan relations

- Japan–United States relations