Relative atomic mass

Relative atomic mass (symbol: Ar) is a dimensionless physical quantity, the ratio of the average mass of atoms of an element (from a single given sample or source) to 1⁄12 of the mass of an atom of carbon-12 (known as the unified atomic mass unit).[1][2] The relative atomic mass is a statistical term, referring to an abundance-weighted figure involving measurement of many atoms. As in all related terms, the word "relative" refers to making the figure relative to carbon-12, so that the final figure is dimensionless.

The term relative atomic mass is exactly equivalent to atomic weight, which is the older term. In technical usage, these values are sample-specific (i.e., element source-specific) when a natural element source is composed of more than one isotope. Thus, two samples of a chemical element which is naturally found as being composed of more than one isotope, collected from two substantially different sources, are expected to give slightly different relative atomic masses (atomic weights), because isotopic concentrations typically vary slightly due to the history (origin) of the source. These values differences are real and repeatable, and can be used to identify specific samples. For example, a sample of elemental carbon from volcanic methane will have a different relative atomic mass (atomic weight) than one collected from plant or animal tissues (for more, see isotope geochemistry). In short, the atomic weight (relative atomic mass) of carbon varies slightly from place to place and from source to source, a fact that can be useful. However, a typical (standard) figure also can be useful, as follows.

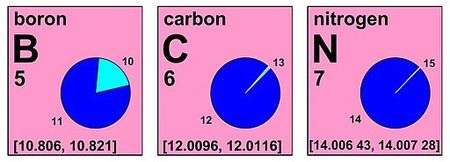

Both the terms relative atomic mass and atomic weight are sometimes loosely used to refer to a technically different standardized expectation value, called the standard atomic weight. This value is the mean value of atomic weights of a number of "normal samples" of the element in question. For this definition, "[a] normal sample is any reasonably possible source of the element or its compounds in commerce for industry and science and has not been subject to significant modification of isotopic composition within a geologically brief period."[3] These standard atomic weights are published at regular intervals by the Commission on Isotopic Abundances and Atomic Weights of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).[4][5] The "standard" values are intended as mean values that compensate for small variances in the isotopic composition of the chemical elements across a range of ordinary samples on Earth, and thus to be applicable to normal laboratory materials. However, they may not accurately reflect values from samples from unusual locations or extraterrestrial objects, which often have more widely variant isotopic compositions.

The standard atomic weights are reprinted in a wide variety of textbooks, commercial catalogues, Periodic Table wall charts etc., and in the table below. They are what chemists loosely call "atomic weights."

The continued use of the term "atomic weight" (of any element), as opposed to "relative atomic mass" has attracted considerable controversy, since at least the 1960s, mainly due to the technical difference between weight and mass in physics.[6] (see below). Both terms are officially sanctioned by IUPAC. The term "relative atomic mass" now seems to be gaining as the preferred term over "atomic weight," although in the case of "standard atomic weight," this shorter term (as opposed to "standard relative atomic mass") continues to be preferred.

Definition (and closely related term)

- Relative atomic mass (not to be confused with relative isotopic mass) is a synonym for atomic weight, and in some circumstances may even be synonymous with standard atomic weight (depending on the sample, see below). It is an average atomic mass, or the weighted mean of the atomic masses of all the atoms of a particular chemical element found in a particular sample, which is then standardized by comparison to carbon-12.[7] Relative atomic mass is frequently used as a synonym for the standard atomic weight and it is correct to do so if the relative atomic mass used is that for an element from Earth under defined conditions. However, relative atomic mass covers more than standard atomic weights, and is a less specific term that may more broadly refer to non-terrestrial environments and highly specific terrestrial environments that deviate from Earth-average or have different certainties (number of significant figures) than do the standard atomic weights.

- Standard atomic weight refers to the expected relative atomic mass or atomic weight of an element sample in the local environment of the Earth's crust and atmosphere as determined by the IUPAC Commission on Atomic Weights and Isotopic Abundances.[8] Because these standard atomic weights are an average (mean) of relative isotopic masses for a given element from different sources (places on Earth), standard atomic weights are subject to natural variation. An uncertainty in brackets or an expectation interval may therefore be included in sources of standard atomic weights (see example in illustration immediately above). This uncertainty reflects natural variability in isotopic distribution for an element, rather than uncertainty in measurement (which is much smaller with quality instruments).[9]

Although there is an attempt to cover the range of variability on Earth with standard atomic weight figures, there are known cases of mineral samples which contain elements with atomic weights that are outliers from the standard atomic weight range.[10]

Lithium represents a unique case where the natural abundances of the isotopes have in some cases been found to have been perturbed by human isotopic separation activities to the point of affecting the uncertainty in its standard atomic weight, even in samples obtained from natural sources, such as rivers.

For synthetic elements the isotope formed depends on the means of synthesis, so the concept of natural isotope abundance has no meaning. Therefore, for synthetic elements the total nucleon count of the most stable isotope (i.e., the isotope with the longest half-life) is listed in brackets, in place of the standard atomic weight.

When the term "atomic weight" is used in chemistry, usually it is the more specific standard atomic weight that is implied. It is standard atomic weights that are used in periodic tables and many standard references in ordinary terrestrial chemistry.

Current definition

Prevailing IUPAC definitions taken from the "Gold Book" are

- atomic weight — See: relative atomic mass[11]

and

- relative atomic mass (atomic weight) — The ratio of the average mass of the atom to the unified atomic mass unit.[12]

Here the "unified atomic mass unit" refers to 1⁄12 of the mass of an atom of 12C in its ground state.[13]

The IUPAC definition[1] of relative atomic mass is:

An atomic weight (relative atomic mass) of an element from a specified source is the ratio of the average mass per atom of the element to 1/12 of the mass of an atom of 12C.

The definition deliberately specifies "An atomic weight…", as an element will have different relative atomic masses depending on the source. For example, boron from Turkey has a lower relative atomic mass than boron from California, because of its different isotopic composition.[14][15] Nevertheless, given the cost and difficulty of isotope analysis, it is usual to use the tabulated values of standard atomic weights which are ubiquitous in chemical laboratories.

Historical amu

Older (pre-1961) historical relative scales (based on the atomic mass unit, or a.m.u., or amu) used either the oxygen-16 relative isotopic mass for reference, or else the oxygen relative atomic mass (i.e., atomic weight) for reference. See the article on the history of the modern unified atomic mass unit for the resolution of these problems in 1961.

Differing terms referring to the mass of single atoms

- Relative isotopic mass is a similar-sounding term which refers to a quite different quantity, specifically the ratio of the mass of a single atom to the mass of a unified atomic mass unit, expressed as a dimensionless number. The relative isotopic mass (of single atoms, etc.) is discussed in the article on atomic mass, with which it is synonymous, save for choice of mass units.

Naming controversy

The use of the name "atomic weight" has attracted a great deal of controversy among scientists.[6] Objectors to the name usually prefer the term "relative atomic mass" (not to be confused with atomic mass). The basic objection is that atomic weight is not a weight, that is the force exerted on an object in a gravitational field, measured in units of force such as the newton or poundal.

In reply, supporters of the term "atomic weight" point out (among other arguments)[6] that

- the name has been in continuous use for the same quantity since it was first conceptualized in 1808;[16]

- for most of that time, atomic weights really were measured by weighing (that is by gravimetric analysis) and the name of a physical quantity should not change simply because the method of its determination has changed;

- the term "relative atomic mass" should be reserved for the mass of a specific nuclide (or isotope), while "atomic weight" be used for the weighted mean of the atomic masses over all the atoms in the sample;

- it is not uncommon to have misleading names of physical quantities which are retained for historical reasons, such as

- electromotive force, which is not a force

- resolving power, which is not a power quantity

- molar concentration, which is not a molar quantity (a quantity expressed per unit amount of substance).

It could be added that atomic weight is often not truly "atomic" either, as it does not correspond to the property of any individual atom. The same argument could be made against "relative atomic mass" used in this sense.

Determination of relative atomic mass

Modern relative atomic masses (a term specific to a given element sample) are calculated from measured values of atomic mass (for each nuclide) and isotopic composition of a sample. Highly accurate atomic masses are available[17][18] for virtually all non-radioactive nuclides, but isotopic compositions are both harder to measure to high precision and more subject to variation between samples.[19][20] For this reason, the relative atomic masses of the 22 mononuclidic elements (which are the same as the isotopic masses for each of the single naturally occurring nuclides of these elements) are known to especially high accuracy. For example, there is an uncertainty of only one part in 38 million for the relative atomic mass of fluorine, a precision which is greater than the current best value for the Avogadro constant (one part in 20 million).

| Isotope | Atomic mass[18] | Abundance[19] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | Range | ||

| 28Si | 27.976 926 532 46(194) | 92.2297(7)% | 92.21–92.25% |

| 29Si | 28.976 494 700(22) | 4.6832(5)% | 4.67–4.69% |

| 30Si | 29.973 770 171(32) | 3.0872(5)% | 3.08–3.10% |

The calculation is exemplified for silicon, whose relative atomic mass is especially important in metrology. Silicon exists in nature as a mixture of three isotopes: 28Si, 29Si and 30Si. The atomic masses of these nuclides are known to a precision of one part in 14 billion for 28Si and about one part in one billion for the others. However the range of natural abundance for the isotopes is such that the standard abundance can only be given to about ±0.001% (see table). The calculation is

- Ar(Si) = (27.97693 × 0.922297) + (28.97649 × 0.046832) + (29.97377 × 0.030872) = 28.0854

The estimation of the uncertainty is complicated,[21] especially as the sample distribution is not necessarily symmetrical: the IUPAC standard relative atomic masses are quoted with estimated symmetrical uncertainties,[22] and the value for silicon is 28.0855(3). The relative standard uncertainty in this value is 1×10–5 or 10 ppm. To further reflect this natural variability, in 2010, IUPAC made the decision to list the relative atomic masses of 10 elements as an interval rather than a fixed number.[23]

Periodic table with relative atomic masses

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group → | ||||||||||||||||||

| ↓ Period | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | H 1.008 | He4.003 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li6.94 | Be9.012 | B 10.81 | C 12.01 | N 14.01 | O 16.00 | F 19.00 | Ne20.18 | ||||||||||

| 3 | Na22.99 | Mg24.31 | Al26.98 | Si28.09 | P 30.97 | S 32.06 | Cl35.45 | Ar39.95 | ||||||||||

| 4 | K 39.10 | Ca40.08 | Sc44.96 | Ti47.87 | V 50.94 | Cr52.00 | Mn54.94 | Fe55.85 | Co58.93 | Ni58.69 | Cu63.55 | Zn65.38 | Ga69.72 | Ge72.63 | As74.92 | Se78.97 | Br79.90 | Kr83.80 |

| 5 | Rb85.47 | Sr87.62 | Y 88.91 | Zr91.22 | Nb92.91 | Mo95.95 | Tc[98] | Ru101.07 | Rh102.91 | Pd106.42 | Ag107.87 | Cd112.41 | In114.82 | Sn118.71 | Sb121.76 | Te127.60 | I 126.90 | Xe131.29 |

| 6 | Cs132.91 | Ba137.33 | |

Hf178.49 | Ta180.95 | W 183.84 | Re186.21 | Os190.23 | Ir192.22 | Pt195.08 | Au196.97 | Hg200.59 | Tl204.38 | Pb207.2 | Bi208.98 | Po[209] | At[210] | Rn[222] |

| 7 | Fr[223] | Ra[226] | |

Rf[267] | Db[268] | Sg[271] | Bh[270] | Hs[277] | Mt[278] | Ds[281] | Rg[282] | Cn[285] | Nh[286] | Fl[289] | Mc[289] | Lv[293] | Ts[294] | Og[294] |

| |

La138.91 | Ce140.12 | Pr140.91 | Nd144.24 | Pm[145] | Sm150.36 | Eu151.96 | Gd157.25 | Tb158.93 | Dy162.50 | Ho164.93 | Er167.26 | Tm168.93 | Yb173.05 | Lu174.97 | |||

| |

Ac[227] | Th232.04 | Pa231.04 | U 238.03 | Np[237] | Pu[244] | Am[243] | Cm[247] | Bk[247] | Cf[251] | Es[252] | Fm[257] | Md[258] | No[259] | Lr[266] | |||

| Legend for the periodic table | ||||

| ||||

See also

- International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC)

- Commission on Isotopic Abundances and Atomic Weights

References

- 1 2 International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1980). "Atomic Weights of the Elements 1979". Pure Appl. Chem. 52 (10): 2349–84. doi:10.1351/pac198052102349.

- ↑ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry, 2nd edition, Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03583-8. p. 41. Electronic version.

- ↑ Definition of element sample

- ↑ The latest edition is International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2006). "Atomic Weights of the Elements 2005". Pure Appl. Chem. 78 (11): 2051–66. doi:10.1351/pac200678112051.

- ↑ The updated list of standard atomic weights is expected to be formally published in late 2008. The IUPAC(International Union Of Pure And Applied Chemistry) Commission on Isotopic Abundances and Atomic Weights announced in August 2007 that the standard atomic weights of the following elements would be revised (new figures quoted here): lutetium 174.9668(1); molybdenum 95.96(2); nickel 58.6934(4); ytterbium 173.054(5); zinc 65.38(2). The recommended value for the isotope amount ratio of 40Ar/36Ar (which could be useful as a control measurement in argon–argon dating) was also changed from 296.03(53) to 298.56(31).

- 1 2 3 de Bièvre, P.; Peiser, H. S. (1992). "'Atomic Weight'—The Name, Its History, Definition, and Units". Pure Appl. Chem. 64 (10): 1535–43. doi:10.1351/pac199264101535.

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "relative atomic mass".

- ↑ IUPAC Definition of Standard Atomic Weight

- ↑ ATOMIC WEIGHTS OF THE ELEMENTS 2005 (IUPAC TECHNICAL REPORT), M. E. WIESER Pure Appl. Chem., V.78, pp. 2051, 2006

- ↑ Definition of standard atomic weights: "Recommended values of relative atomic masses of the elements revised biennially by the IUPAC Commission on Atomic Weights and Isotopic Abundances and applicable to elements in any normal sample with a high level of confidence. A normal sample is any reasonably possible source of the element or its compounds in commerce for industry and science and has not been subject to significant modification of isotopic composition within a geologically brief period."

- ↑ IUPAC Gold Book - atomic weight

- ↑ IUPAC Gold Book - relative atomic mass (atomic weight), A r

- ↑ IUPAC Gold Book - unified atomic mass unit

- ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1984). Chemistry of the Elements. Oxford: Pergamon Press. pp. 21, 160. ISBN 0-08-022057-6.

- ↑ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2003). "Atomic Weights of the Elements: Review 2000". Pure Appl. Chem. 75 (6): 683–800. doi:10.1351/pac200375060683.

- ↑ Dalton, John (1808). A New System of Chemical Philosophy. Manchester.

- ↑ National Institute of Standards and Technology. Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for All Elements.

- 1 2 Wapstra, A.H.; Audi, G.; Thibault, C. (2003), The AME2003 Atomic Mass Evaluation (Online ed.), National Nuclear Data Center. Based on:

- Wapstra, A.H.; Audi, G.; Thibault, C. (2003), "The AME2003 atomic mass evaluation (I)", Nuclear Physics A, 729: 129–336, Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729..129W, doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.002

- Audi, G.; Wapstra, A.H.; Thibault, C. (2003), "The AME2003 atomic mass evaluation (II)", Nuclear Physics A, 729: 337–676, Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729..337A, doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.003

- 1 2 Rosman, K. J. R.; Taylor, P. D. P. (1998), "Isotopic Compositions of the Elements 1997" (PDF), Pure and Applied Chemistry, 70 (1): 217–35, doi:10.1351/pac199870010217

- ↑ Coplen, T. B.; et al. (2002), "Isotopic Abundance Variations of Selected Elements" (PDF), Pure and Applied Chemistry, 74 (10): 1987–2017, doi:10.1351/pac200274101987

- ↑ Meija, Juris; Mester, Zoltán (2008). "Uncertainty propagation of atomic weight measurement results". Metrologia. 45: 53–62. Bibcode:2008Metro..45...53M. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/45/1/008.

- ↑ Holden, Norman E. (2004). "Atomic Weights and the International Committee—A Historical Review". Chemistry International. 26 (1): 4–7.

- ↑ IUPAC - International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry: Atomic Weights of Ten Chemical Elements About to Change

External links

- IUPAC Commission on Isotopic Abundances and Atomic Weights

- NIST relative atomic masses of all isotopes and the standard atomic weights of the elements

- Atomic Weights of the Elements 2011