Unified Task Force

| Operation Restore Hope | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Somali Civil War | |||||||

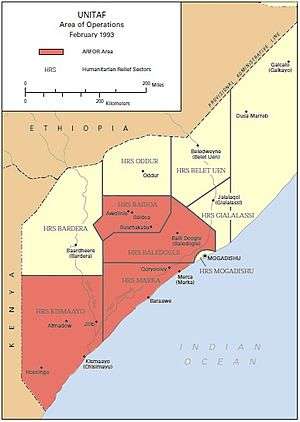

UNITAF Area of Operations, February 1993 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| see Composition of UNITAF | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

US: 53 killed 153 wounded[1] (Includes UNOSOM II casualties) Italy: 3 killed 36 wounded Australia: 1 killed 3 wounded Canada: 1 killed[2] Belgium: 3 killed 2+ wounded Malaysia: 1 killed Greece: 1 killed Pakistan: 39-60 Killed 75+ wounded Malaysia: 5 Killed 23 wounded Turkey: 4 Wounded | Not known | ||||||

The Unified Task Force (UNITAF) was a US-led, United Nations-sanctioned multinational force, which operated in Somalia between 5 December 1992 – 4 May 1993. A United States initiative (code-named Operation Restore Hope), UNITAF was charged with carrying out United Nations Security Council Resolution 794 to create a protected environment for conducting humanitarian operations in the southern half of the country.

After the killing of several Pakistani peacekeepers, the Security Council changed UNITAF's mandate issuing the Resolution 837 that establishes that UNITAF troops could use "all necessary measures" to guarantee the delivery of humanitarian aid in accordance to Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter,[3] and is regarded as a success.[4]

Background

Faced with a humanitarian disaster in Somalia, exacerbated by a complete breakdown in civil order, the United Nations had created the UNOSOM I mission in April 1992. However, the complete intransigence of the local faction leaders operating in Somalia and their rivalries with each other meant that UNOSOM I could not be performed. The mission never reached its mandated strength.[5]

Over the final quarter of 1992, the situation in Somalia continued to worsen. Factions were splintering into smaller factions, and then splintered again. Agreements for food distribution with one party were worthless when the stores had to be shipped through the territory of another. Some elements were actively opposing the UNOSOM intervention. Troops were shot at, aid ships attacked and prevented from docking, cargo aircraft were fired upon and aid agencies, public and private, were subject to threats, looting and extortion.[5]

By November, General Mohamed Farrah Aidid had grown confident enough to defy the Security Council formally and demand the withdrawal of peacekeepers, as well as declaring hostile intent against any further UN deployments.[6]

In the face of mounting public pressure and frustration, UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali presented several options to the Security Council. Diplomatic avenues having proved largely fruitless, he recommended that a significant show of force was required to bring the armed groups to heel. Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations allows for "action by air, sea or land forces as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security." Boutros-Ghali believed the time had come for employing this clause and moving on from peacekeeping.[7]

.jpg)

However, Boutros-Ghali felt that such action would be difficult to apply under the mandate for UNOSOM. Moreover, he realised that solving Somalia’s problems would require such a large deployment that the UN Secretariat did not have the skills to command and control it. Accordingly, he recommended that a large intervention force be constituted under the command of member states but authorised by the Security Council to carry out operations in Somalia. The goal of this deployment was "to prepare the way for a return to peacekeeping and post-conflict peace-building".[5]

Following this recommendation, on 3 December 1992 the Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 794, authorizing the use of "all necessary means to establish as soon as possible a secure environment for humanitarian relief operations in Somalia". The Security Council urged the Secretary-General and member states to make arrangements for "the unified command and control" of the military forces that would be involved.[8]

UNITAF has been considered part of a larger state building initiative in Somalia, serving as the military arm to secure the distribution of humanitarian aid. However, UNITAF cannot be considered a state building initiative due to its ‘specific, limited and palliative aims, which it nonetheless exercised forcefully’. The primary objective of UNITAF was security rather than larger institution building initiatives.[9]

U.S. involvement

Prior to Resolution 794, the United States had approached the UN and offered a significant troop contribution to Somalia, with the caveat that these personnel would not be commanded by the UN. Resolution 794 did not specifically identify the U.S. as being responsible for the future task force, but mentioned "the offer by a Member State described in the Secretary-General's letter to the Council of 29 November 1992 (S/24868) concerning the establishment of an operation to create such a secure environment".[10] Resolution 794 was unanimously adopted by the United Nations Security Council on 3 December 1992, and they welcomed the United States offer to help create a secure environment for humanitarian efforts in Somalia.[11] President George H. W. Bush responded to this by initiating Operation Restore Hope on 4 December 1992, under which the United States would assume command in accordance with Resolution 794.[12] CIA Paramilitary Officer Larry Freedman from their Special Activities Division became the first US casualty of the conflict in Somalia when his vehicle struck an anti-tank mine. He had been inserted prior to official US presence on a special reconnaissance mission, serving as a liaison between the U.S. Embassy and the arriving military forces while providing intelligence for both. Freedman was a former Army Delta Force operator and Special Forces soldier and had served in every conflict that the US was involved in both officially and unofficially since Vietnam. Freedman was awarded the Intelligence Star for extraordinary heroism.[13]

The first Marines of UNITAF landed on the beaches of Somalia on 9 December 1992 amid a media circus. The press "seemed to know the exact time and place of the Marines' arrival" and waited on the airport runway and beaches to capture the moment.[14]

Critics of US involvement argued that the US government was intervening so as to gain control of oil concessions for American companies,[15] with a survey of Northeast Africa by the World Bank and UN ranking Somalia second only to Sudan as the top prospective producer.[16] However, no US and UN troops were deployed in proximity to the major oil exploration areas in the northeastern part of the country or the autonomous Somaliland region in the northwest. The intervention happened twenty-two months after the fall of Barre's regime.[17] Other critics explain the intervention as the administration's way to maintain the size and expenditures of the post-Cold War military establishment, to deflect criticism for the president's failure to act in Bosnia, or to leave office on a high note.[17]

Composition of UNITAF

The vast bulk of UNITAF's total personnel strength was provided by the United States (some 25,000 out of a total of 37,000 personnel). Other countries that contributed to UNITAF were Australia, Bangladesh, Belgium, Botswana, Canada, Egypt, Ethiopia, France, Germany, Greece, India, Republic of Ireland, Italy, Kuwait, Morocco, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Sweden, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and Zimbabwe.[3]

The U.S. Central Command (USCINCCENT) established Joint Task Force (JTF) Somalia to perform Operation Restore Hope. The I Marine Expeditionary Force (I MEF) staff made up the core of the JTF headquarters. (The name of this command started as CJTF Somalia but changed to United Task Force-UNITAF). The CJTF commanded Marine forces from I MEF (referred to as MARFOR) and Army forces from the 10th Mountain Division (referred to as ARFOR), as well as Air Force and Navy personnel and units.[18] There were also special operations forces components, in addition to the forces provided by countries contributing to the US-led, combined coalition.

The national contingents were co-ordinated and overseen by U.S. Central Command, however, the relationship between CentCom and the contributing nations varied. There were a few confrontations over the methods and mandates employed by some contingents. For example, the Italian contingent was accused of bribing local militias to maintain peace, whilst the French Foreign Legion troops were accused of over-vigorous use of force in disarming militiamen.[19] The Canadian contingent of the operation was known by the Canadian operation name Operation Deliverance. Following the Somalia Affair probe, the Canadian Airborne Regiment was disbanded.

Operation

The operation began on 6 December 1992, when U.S. Navy SEALs and Special Boat crewmen from Naval Special Warfare Task Unit TRIPOLI began conducting reconnaissance operations in the vicinity of the airport and harbor. These operations lasted three days. In the early hours of 8 December 1992 elements of the Army's 4th Psychological Operations Group (Airborne) attached to the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) conducted leaflet drops over the capital city of Mogadishu.[20][21] Early on 9 December, the MEU performed an unopposed amphibious assault into the city of Mogadishu from USS Tripoli (LPH-10), USS Juneau (LPD-10) and USS Rushmore (LSD-47).[22][23]:16

The MEU's ground combat element, 2nd Battalion 9th Marines (2/9), performed simultaneous raids on the Port of Mogadishu and Mogadishu International Airport, establishing a foothold for additional incoming troops. Echo and Golf Company assaulted the airport by helicopter and Amphibious Assault Vehicles, while Fox Company secured the port with an economy of force rubber boat raid. The 1st Marine Division's Air Contingency Battalion (ACB), 1st Battalion, 7th Marines and 3rd Battalion 11th Marines (3/11 is an Artillery Unit but operated as a Provisional Infantry Battalion while in Somalia), arrived soon after the airport was secured. Elements of BLT 3/9 India Co, 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines and 1/7 went on to secure the airport in Baidoa and the city of Bardera while Golf Company 2/9 and elements of the Belgian Special Forces conducted an amphibious landing at the port city of Kismayo. Air support was provided by the combined helicopter units of HMLA-267, HMH-363, HMH-466, HMM-164 and HC-11 DET 10.

Concurrently, various Somali factions returned to the negotiating table in an attempt to end the civil war. This effort was known as the Conference on National Reconciliation in Somalia and it resulted in the Addis Ababa Agreement signed on 27 March 1993. The conference, however, had little result as the civil war continued afterwards.

Results

As UNITAF's mandate was to protect the delivery of food and other humanitarian aid, the operation was regarded as a success.[24] United Nations Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali determined that the presence of UNITAF troops had a "positive impact on the security situation in Somalia and on the effective delivery of humanitarian assistance."[25] An estimated 100,000 lives were saved as a result of outside assistance.[26]

One day prior to the signing of the Addis Ababa Agreement, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 814, which marked the transfer of power from UNITAF to UNOSOM II, a United Nations led force. The major change in policy that the transition from UNITAF to UNOSOM II entailed is that the new mandate included the responsibility of nation-building on the multinational force.[27] On 3 May 1993, UNOSOM II officially assumed command, and on 4 May 1993 it assumed responsibility for the operations.

Operation Continue Hope provided support of UNOSOM II to establish a secure environment for humanitarian relief operations by providing personnel, logistical, communications, intelligence support, a quick reaction force, and other elements as required. Over 60 Army aircraft and approximately 1,000 aviation personnel operated in Somalia from 1992 to 1994.

Crucially however, no disarmament of the rivaling factions within Somalia was undertaken.[28] This meant that the situation stayed stable only for the time UNITAF's overwhelming presence was deterring the fighting. Therefore, the mandate to create a "secure environment" was not achieved in a durable fashion.

UNITAF transition

UNITAF was only intended as a transitional body. Once a secure environment had been restored, the suspended UNOSOM mission would be revived, albeit in a much more robust form. On 3 March 1993, the Secretary-General submitted to the Security Council his recommendations for effecting the transition from UNITAF to UNOSOM II. He noted that despite the size of the UNITAF mission, a secure environment was not yet established and there was still no effective functioning government or local security/police force.[29]

The Secretary-General concluded therefore, that, should the Security Council determine that the time had come for the transition from UNITAF to UNOSOM II, the latter should be endowed with enforcement powers under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter to establish a secure environment throughout Somalia.[5] UNOSOM II would therefore seek to complete the task begun by UNITAF for the restoration of peace and stability in Somalia. The new mandate would also empower UNOSOM II to assist the Somali people in rebuilding their economic, political and social life, through achieving national reconciliation so as to recreate a democratic Somali State.

UNOSOM II was established by the Security Council in Resolution 814 on 26 March 1993 and formally took over operations in Somalia when UNITAF was dissolved on 4 May 1993.

References

- ↑ https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RL32492.pdf

- ↑ "United Nations Operation in Somalia UNSOM 1992". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- 1 2 "United Nations Operation In Somalia I – (Unosom I)". Un.org. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ↑ "Operation Restore Hope". Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- 1 2 3 4 "UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN SOMALIA I, UN Dept of Peacekeeping". Un.org. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ↑ United Nations, 1992, Letter dated 92/11/24 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council.

- ↑ United Nations, 1992, Letter dated 92/11/29 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council, page 6.

- ↑ United Nations, Security Council resolution 794 (1992), 24 April 1992, para. 3

- ↑ Caplan, Richard (2012). Exit Strategies and State Building. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 86. ISBN 9780199760121.

- ↑ "Security Council resolutions – 1992". Un.org. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ↑ Security Council Resolution 794

- ↑ Bush, George H., Address to the Nation on the Situation in Somalia, 4/12/92 On 23 December 1992,

- ↑ Michael Robert Patterson. "Lawrence N. Freedman, Sergeant Major, United States Army". Arlingtoncemetery.net. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ↑ Johnston, Dr. Philip (1994). Somalia Diary: The President of CARE Tells One Country's Story of Hope. Atlanta, Georgia: Longstreet Press. p. 73. ISBN 1-56352-188-1.

- ↑ Fineman, Mark (18 January 1993). "Column One; The Oil Factor In Somalia;Four American Petroleum Giants Had Agreements With The African Nation Before Its Civil War Began. They Could Reap Big Rewards If Peace Is Restored". Los Angeles Times: 1.

- ↑ Reuters 21 May 2008 (2008-05-21). "Canada's Africa Oil Starts Somalia Seismic Survey". Theepochtimes.com. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- 1 2 Adam, Dr. Hussein M. (2008). From Tyranny to Anarchy: The Somali Experience. Trenton, NJ: The Red Sea Press, Inc. pp. 156–160. ISBN 1-56902-288-7.

- ↑ Relations with Humanitarian Relief Organizations: Observations from Restore Hope, Center for Naval Analysis

- ↑ Patman, R.G., 2001, ‘Beyond ‘the Mogadishu Line’: Some Australian Lessons for Managing Intra-State Conflicts’, Small Wars and Insurgencies, Vol, 12, No. 1, p. 69

- ↑ Friedman, Herbert A. "United States PSYOP in Somalia". Psywarrior. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- ↑ Borchini, Charles P. (Lt. Col.); Borstelmann, Mari (October 1994). "PSYOP in Somalia: The Voice of Hope" (PDF). Special Warfare. United States Army. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- ↑ Buer, Eric F. (Maj.) (2002). "A Comparative Analysis of Offensive Air Support" (PDF). United States Marine Corps Command and Staff College. p. 23.

- ↑ Mroczkowski, Dennis P. (Col.) (2005). Restoring Hope: In Somalia with the Unified Task Force 1992–1993. United States Marines Corp. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- ↑ "Operation Restore Hope". Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ "United Nations Operation in Somalia I". Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ "Somalia and the Future of Humanitarian Intervention". Foreign Affairs.

- ↑ "United Nations Operation in Somalia 2". Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ Norrie MacQueen (2006). Peacekeeping and the International System. Routledge.

- ↑ UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN SOMALIA I, UN Dept of Peacekeeping

Further reading

- Allard, Colonel Kenneth, Somalia Operations: Lessons Learned, National Defense University Press (1995).

- Miller, Laura L. and Charles Moskos. "Humanitarians or Warriors?: Race, Gender, and Combat Status in Operations Restore Hope"' Armed Forces & Society, Jul 1995; vol. 21: pp. 615–637

- Stevenson, Jonathan (1995). Losing Mogadishu: Testing U.S. Policy in Somalia. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1557507880. OCLC 31435791.

- Stewart, Dr. Richard W. The United States Army in Somalia 1992–1994. Washington D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 70-81-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Unified Task Force. |

- Bibliography of Contingency Operations: Somalia (Restore Hope) compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History

- UN Department of Peacekeeping: UNOSOM 1

- UN Department of Peacekeeping: UNOSOM 2

- Global Security on Operation Restore Hope