Banana Wars

| Banana Wars | |

|---|---|

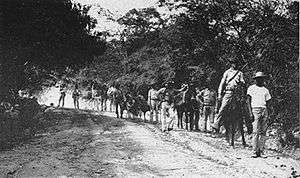

United States Marines and a Haitian guide patrolling the jungle in 1915 during the Battle of Fort Dipitie | |

| Objective | Protect United States interests in Central America |

| Date | 1898–1934 |

| Executed by | United States |

| Outcome | Spanish–American War Santo Domingo Affair Second Occupation of Cuba Border War Negro Rebellion Occupation of Nicaragua Occupation of Haiti Occupation of the Dominican Republic Sugar Intervention |

Banana Wars is the term used by some historians since it was coined in 1983[1] to refer to the occupations, police actions, and interventions on the part of the United States in Central America and the Caribbean between the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898 and the inception of the Good Neighbor Policy in 1934.[2] These military interventions were most often carried out by the United States Marine Corps, which developed a manual, The Strategy and Tactics of Small Wars (1921) based on its experiences. On occasion, the Navy provided gunfire support and Army troops were also used.

With the Treaty of Paris, Spain ceded control of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines to the United States. Thereafter, the United States conducted military interventions in Cuba, Panama, Honduras, Nicaragua, Mexico, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. The series of conflicts ended with the withdrawal of troops from Haiti in 1934 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Origins

US motivations for these conflicts were largely economic and military. The term "Banana Wars" was coined much later to cast the motivations for these interventions as almost exclusively the preservation of petty US commercial interests in the region.

Most prominently, the US was advancing its economic, political, and military interests to maintain its sphere of influence and securing the Panama Canal (opened 1914) which it had recently built to promote global trade and to project its own naval power. US companies like the United Fruit Company also had financial stakes in the production of bananas, tobacco, sugar cane, and other commodities throughout the Caribbean, Central America and Northern South America.

Interventions

- Spanish–American War, U.S. forces seize Cuba and Puerto Rico from Spain in 1898.

- Panama, U.S. interventions in the isthmus go back to the 1846 Mallarino–Bidlack Treaty and intensified after the so-called Watermelon War of 1856. In 1903, Panama seceded from the Republic of Colombia, backed by the U.S. government,[lower-alpha 1] during the Thousand Days' War. The Panama Canal was under construction by then, and the Panama Canal Zone, under United States sovereignty, was created.

- Nicaragua, which, after intermittent landings and naval bombardments in the previous decades, was occupied by the U.S. almost continuously from 1912–1933.

- Cuba, occupied by the U.S. from 1898–1902 under military governor Leonard Wood, and again from 1906 to 1909, 1912, and 1917 to 1922; subject to the terms of the Cuban–American Treaty of Relations (1903) until 1934.

- Haiti, occupied by the U.S. from 1915–1934, which led to the creation of a new Haitian constitution in 1917 that instituted changes that included an end to the prior ban on land ownership by non-Haitians. This period included the First and Second Caco Wars.[4]

- Dominican Republic, action in 1903, 1904 (the Santo Domingo Affair), and 1914 (Naval forces engage in battles in the city of Santo Domingo[5]); occupied by the U.S. from 1916 to 1924.

- Honduras, where the United Fruit Company and Standard Fruit Company dominated the country's key banana export sector and associated land holdings and railways, saw insertion of American troops in 1903, 1907, 1911, 1912, 1919, 1924 and 1925. The writer O. Henry coined the term "Banana republic" in 1904 to describe Honduras.[6]

- Mexico, The U.S. military involvements with Mexico in this period are related to the same general commercial and political causes, but stand as a special case. The Americans conducted the Border War with Mexico from 1910-1919 for additional reasons: to control the flow of immigrants and refugees from revolutionary Mexico (pacificos), and to counter rebel raids into U.S. territory. The 1914 U.S. occupation of Veracruz, however, was an exercise of armed influence, not an issue of border integrity; it was aimed at cutting off the supplies of German munitions to the government of Mexican leader Victoriano Huerta,[7] which U.S. President Woodrow Wilson refused to recognize.[7] In the years prior to World War I, the U.S. was also alert to the regional balance of power against Germany. The Germans were actively arming and advising the Mexicans, as shown by the 1914 SS Ypiranga arms-shipping incident, German saboteur Lothar Witzke's base in Mexico City, the 1917 Zimmermann Telegram and German advisors present during the 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales. Only twice during the Mexican Revolution did the U.S. military occupy Mexico: during the temporary occupation of Veracruz in 1914 and between 1916 and 1917, when U.S. General John Pershing led U.S. Army forces on a nationwide search for Pancho Villa.

Other Latin American nations were influenced or dominated by American economic policies and/or commercial interests to the point of coercion. Theodore Roosevelt declared the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine in 1904, asserting the right of the United States to intervene to stabilize the economic affairs of states in the Caribbean and Central America if they were unable to pay their international debts. From 1909-1913, President William Howard Taft and his Secretary of State Philander C. Knox asserted a more "peaceful and economic" Dollar Diplomacy foreign policy, although that too was backed by force, as in Nicaragua.

American fruit companies

The first decades of Honduras' history is marked by instability in terms of politics and economy. Indeed, the political context gave way to 210 armed conflicts between independence and the rise to power of the Carias government.[8] This instability was due in part to the American involvement in the country.[8]

The first company that concluded an agreement with the Honduras government was the Vaccaro Brothers Company (Standard Fruit Company).[8] The Cuyamel Fruit Company then followed the lead. Furthermore, the United Fruit Company also agreed to a contract with the government, which contract was attained through its Subsidiaries (Tela Rail Road Company and Truxillo Rail Road Company).[8]

There were different avenues that led to the signature of a contract between the Honduras government and the American companies. The most popular avenue would be to obtain exclusive rights to a piece of land in exchange of the completion of railroads in Honduras.[8] It is, thus, the reason why it is a railroad company that conducted the agreement between the United Fruit Company and Honduras.

However, according to Mark Moberg, most banana producers in Central America (including Honduras) "were scourged by Panama disease, a soil-borne fungus (…) that decimated production over large regions".[9] Typically, when a plantation would be decimated, the companies would abandon the plantation, and destroy the railroads (and other utilities) that they had been using along with the plantation.[9] Therefore, one might argue that the exchange of services between the government and the companies was not always respected.

The ultimate goal in the acquisition of a contract was to control the process from production to distribution of the bananas. Therefore, the companies would finance guerrilla fighters, presidential campaigns and governments.[8] According to Rivera and Carranza, the indirect participation of American companies in the country's armed conflicts worsened the situation.[8] They argued that the presence of more dangerous and modern weapons gave place to more dangerous warfare among the different factions.[8]

In British Honduras, modern-day Belize, the situation was slightly different. Despite the fact that the United Fruit Company was the sole-exporter of bananas in British Honduras and the company was also manipulating the government, the country did not suffer the instability and armed conflicts its neighbors experienced.[9]

Notable veterans

Perhaps the single most active military officer in the Banana Wars was U.S. Marine Corps Major General, Smedley Butler, who saw action in Honduras in 1903, served in Nicaragua enforcing American policy from 1909–1912, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his role in Veracruz in 1914, and a second Medal of Honor for bravery in Haiti in 1915. In 1935, he denounced the role he had played, describing himself as "as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers ... a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism".[10]

Notable U.S. veterans of the Banana Wars include:

- U.S. Army:

- Henry Tureman Allen

- George Brett (general)

- John F. Curry

- John L. DeWitt

- Townsend F. Dodd

- Robert L. Eichelberger

- William P. Ennis

- Muir S. Fairchild

- James Fechet

- James M. Gavin

- Harold Huston George

- Millard Harmon

- Lewis Blaine Hershey

- Geoffrey Keyes

- Walter Krueger

- Lyman Lemnitzer

- Hunter Liggett

- Douglas MacArthur

- William M. Miley

- Henry J. F. Miller

- George Smith Patton

- Vernon Prichard

- Matthew Ridgway

- Theodore Roosevelt

- Ralph Royce

- William Hood Simpson

- Ralph C. Smith

- Joseph Stilwell

- Fred L. Walker

- Walton Walker

- Robert E. Wood

- Roscoe B. Woodruff

- U.S. Navy:

- U.S. Marine Corps:

- Smedley Butler {MOH}

- Evans F. Carlson

- Henry Pierson Crowe

- Louis Cukela {MOH}

- Alfred Austell Cunningham

- Daniel Daly {MOH}

- Pedro del Valle

- James Devereux

- Merritt A. Edson

- Earl Hancock Ellis

- Logan Feland

- Roy Geiger

- Joseph A. Glowin {MOH}

- Frank Goettge

- Herman H. Hanneken {MOH}

- James Harbord

- Field Harris

- Franklin A. Hart

- Lofton Henderson

- Leo D. Hermle

- Samuel L. Howard

- Henry Louis Larsen {MOH}

- John A. Lejeune

- Homer Litzenberg

- Harry B. Liversedge

- William K. MacNulty (Navy Cross)

- Lewie G. Merritt

- John Twiggs Myers

- Francis P. Mulcahy

- Joseph Henry Pendleton

- Chesty Puller

- Paul A. Putnam

- John H. Quick {MOH}

- Francis D. Rauber

- Keller E. Rockey

- William H. Rupertus

- John H. Russell, Jr.

- Christian F. Schilt {MOH}

- Frank Schwable

- Holland Smith

- Oliver P. Smith

- Donald L. Truesdale {MOH}

- William P. Upshur {MOH}

- Alexander Vandegrift

- Littleton Waller

- Thomas E. Watson (USMC)

- Ernest C. Williams {MOH}

- Roswell Winans {MOH}

- Louis E. Woods

Notes

References

- ↑ Langley, Lester D. (1983). The Banana Wars: United States Intervention in the Caribbean, 1898–1934. University Press of Kentucky. p. 3. ISBN 0-8131-1496-9.

- ↑ Gilderhusrt, Mark T. (2000). The Second Century: U.S.--Latin American Relations Since 1889. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 49.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Theodore (December 7, 1903).

Theodore Roosevelt's Third State of the Union Address. Wikisource.

Theodore Roosevelt's Third State of the Union Address. Wikisource. - ↑ Hubert, Giles A. (January 1947). "War and the Trade Orientation of Haiti". Southern Economic Journal. 13 (3): 276–84. JSTOR 1053341.

- ↑ "US Military and Clandestine Operations in Foreign Countries - 1798-Present".

- ↑ Economist explains (November 21, 2013). "Where did banana republics get their name?". economist.com. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- 1 2 "Mexican Revolution: Battle of Veracruz". Militaryhistory.about.com. August 4, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Miguel Cáceres Rivera and Sucelinda Zelaya Carranza, "Honduras. Seguridad Productiva y Crecimiento Econoómico: La Función Económica Del Cariato," Anuario de Estudios Centroamericanos, Vol. 31 (2005), pp. 49–91.

- 1 2 3 Mark Moberg, "Crown Colony as Banana Republic: The United Fruit Company in British Honduras, 1900-1920," Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 28, No. 2 (May 1996), pp. 357–381.

- ↑ Butler, Smedley (1935). War Is a Racket. Round Table Press.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Banana Wars. |