Remilitarization of the Rhineland

| Territorial evolution of Germany in the 20th century |

|---|

|

Pre-World War II

|

|

Post-World War II

|

|

Adjacent countries |

| Events leading to World War II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

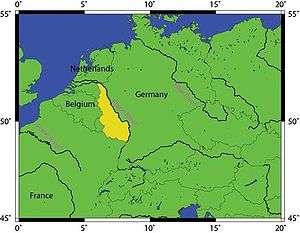

The remilitarization of the Rhineland by the German Army took place on 7 March 1936 when German military forces entered the Rhineland. This was significant because it violated the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Treaties, marking the first time since the end of World War I that German troops had been in this region. The remilitarization changed the balance of power in Europe from France towards Germany, and made it possible for Germany to pursue a policy of aggression in Eastern Europe that the demilitarized status of the Rhineland had blocked until then.

Background

Versailles and Locarno

Under Articles 42, 43 and 44 of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles—imposed on Germany by the Allies after the Great War—Germany was "forbidden to maintain or construct any fortification either on the Left bank of the Rhine or on the Right bank to the west of a line drawn fifty kilometers to the East of the Rhine". If a violation "in any manner whatsoever" of this Article took place, this "shall be regarded as committing a hostile act...and as calculated to disturb the peace of the world".[1] The Locarno Treaties, signed in October 1925 by Germany, France, Italy and Britain, stated that the Rhineland should continue its demilitarized status permanently.[2] Locarno was regarded as important as it was a voluntary German acceptance of the Rhineland's demilitarized status as opposed to the diktat (dictate) of Versailles.[2][3][4][5] Under the terms of Locarno, Britain and Italy guaranteed the Franco-German border and the continued demilitarized status of the Rhineland against a "flagrant violation" without however defining what constituted a "flagrant violation".[6] Under the terms of Locarno, if Germany should attempt to attack France, then Britain and Italy were obliged to go to France's aid and likewise, if France should attack Germany, then Britain and Italy would be obliged to Germany's aid.[4] The American historian Gerhard Weinberg called the demilitarized status of the Rhineland the "single most important guarantee of peace in Europe" as it made it impossible for Germany to attack its neighbors in the West and as the demilitarized zone rendered Germany defenseless in the West, impossible to attack its neighbors in the East as it left Germany open to devastating French offensive if the Reich tried to invade any of the states guaranteed by the French alliance system in Eastern Europe, the so-called Cordon sanitaire.[7]

The Versailles Treaty also stipulated that the Allied military forces would withdraw from the Rhineland in 1935, although they actually withdrew in 1930. The German Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann announced in 1929 that Germany would not ratify the 1928 Young Plan for continuing to pay reparations unless the Allies agreed to leave the Rhineland in 1930. The British delegation at the Hague Conference on German reparations in 1929 (headed by Philip Snowden, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and including Arthur Henderson, Foreign Secretary) proposed that the reparations paid by Germany should be reduced and that the British and French forces should evacuate the Rhineland. Henderson persuaded the skeptical French Premier, Aristide Briand, to accept the proposal that all Allied occupation forces would evacuate the Rhineland by June 1930. The last British soldiers left in late 1929 and the last French soldiers left in June 1930. As long as the French continued to occupy the Rhineland, the Rhineland functioned as a form of "collateral" under which the French would respond to any German attempt at overt rearmament by annexing the Rhineland. It was the fear that the French would take this step that had deterred successive Weimar governments from attempting any overt breaches of Part V and VI of Versailles, which had disarmed Germany (as opposed to covert rearmament which began almost as soon as Versailles was signed). Once the last French soldiers left the Rhineland in June 1930, it could no longer play its "collateral" role, which thus opened the door to German rearmament. The French decision to build the Maginot Line in 1929 (which cost hundreds of millions of francs) was a tacit French admission that it was only a matter of time before German rearmament on a massive scale would begin sometime in the 1930s and that the Rhineland was going to be remilitarized sooner or later.[8][9] Intelligence from the Deuxième Bureau indicated that Germany had been violating Versailles continuously all though the 1920s with the considerable help of the Soviet Union, and with the French troops out of the Rhineland, it could only be expected that Germany would become more open about violating Versailles.[10] The Maginot Line in its turn lessened the importance of the Rhineland's demilitarized status from a French security viewpoint.

The foreign policies of the interested powers

The foreign policy of Fascist Italy was the traditional Italian one of maintaining an "equidistant" stance from all the major powers in order to exercise "determinant weight", which by whatever power Italy chose to align with would decisively change the balance of power in Europe, and the price of such an alignment would be support for Italian ambitions in Europe and/or Africa.[11] The foreign policy goal of the Soviet Union was set forth by Joseph Stalin in a speech on 19 January 1925 that if another world war would break out between the capitalist states (which Stalin saw as inevitable) that: "We will enter the fray at the end, throwing our critical weight onto the scale, a weight that should prove to be decisive".[12] To promote this goal of another world war which would lead to the global triumph of Communism, the Soviet Union tended to support German efforts to challenge the Versailles system by assisting German secret rearmament, a policy that caused much tension with France. An additional problem in Franco-Soviet relations was the Russian debt issue. Before 1917, the French had been by far the largest investors in Imperial Russia, and the largest buyers of Russian debt, so the decision by Lenin in 1918 to repudiate all debts and to confiscate all private property, whatever it be owned by Russians or foreigners had hurt the world of French business and finance quite badly. The question of the Russian debt repudiation and compensation for French businesses affected by Soviet nationalisation policies were to poison Franco-Soviet relations until the early 1930s. The centerpiece of interwar French diplomacy had been the cordon sanitaire in Eastern Europe, which was intended to keep both the Soviet Union and Germany out of Eastern Europe. To this end, France had signed treaties of alliance with Poland in 1921, Czechoslovakia in 1924, Romania in 1926 and Yugoslavia in 1927.[13] The cordon sanitaire states were intended as a collective replacement for Imperial Russia as France's chief eastern ally. The states of the cordon sanitaire emerged as an area of French political, military, economic and cultural influence.[13][14] As regards Germany, it had always been assumed by the states of the cordon sanitaire that if Germany should attack any of them, France would respond by beginning an offensive into western Germany. Long before 1933, German military and diplomatic elites had regarded the Rhineland's demilitarized status as only temporary, and planned to remilitarize the Rhineland at the first favorable diplomatic opportunity.[15] In December 1918, at a meeting of Germany's leading generals (the German Army functioned as a "state within the state"), it had decided that the chief aim would be to rebuild German military power to launch a new world war to win the "world power status" that the Reich had sought, but failed to win in the last war.[16] All through the 1920s and the early 1930s, the Reichswehr had been developing plans for a war to destroy France and its ally Poland, which by their necessity presumed remilitarization of the Rhineland.[17] All through the 1920s, steps had taken by the German government to prepare for the remilitarization such as keeping former barracks in a good state of repair, hiding military materials in secret depots and building customs and fire watch towers that could be easily converted into observation and machine gun posts along the frontier.[18]

From 1919 to 1932, British defense spending was based upon the Ten Year Rule, which assumed that there was to be no major war for the next ten years, a policy that led to the British military being cut to the bone.[19] Amongst British decision-makers, the idea of the "continental commitment" of sending a large army to fight on the European mainland against Germany was never explicitly rejected, but was not favored.[20] The memory of the heavy losses taken in the Great War had led many to see the "continental commitment" of 1914 as a serious mistake. For most of the inter-war period, the British were extremely reluctant to make security commitments in Eastern Europe, regarding the region as too unstable and likely to embroil Britain in unwanted wars. At most, Britain was willing to make only limited security commitments in Western Europe, and even then tried to avoid the "continental commitment" as much as possible. In 1925, the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Austen Chamberlain had famously stated in public at the Locarno conference that the Polish Corridor was "not worth the bones of a single British grenadier".[21][22] As such, Chamberlain declared that Britain would not guarantee the German-Polish border on the grounds that the Polish Corridor should be returned to Germany. That the British did not take even their Locarno commitments seriously could be seen in Whitehall's prohibition of the British military chiefs' holding staff talks with German, French and Italian militaries about what to do if a "flagrant violation" of Locarno occurred.[23] In general, for most of the 1920s–30s, British foreign policy was based upon appeasement, under which the international system established by Versailles would be revised in Germany's favor, within limits in order to win German acceptance of that international order, and thereby ensure the peace. One of the main British aims at Locarno was to create a situation where Germany could pursue territorial revisionism in Eastern Europe peacefully.[24] The British viewpoint was that if Franco-German relations improved, France would gradually abandon the Cordon sanitaire, as the French alliance system in Eastern Europe was known between the wars.[24] Once France had abandoned its allies in Eastern Europe as the price of better relations with the Reich, this would create a situation where the Poles and Czechoslovaks having no Great Power ally to protect them, would be forced to adjust to German demands, and hence would peacefully hand over the territories claimed by Germany such as the Sudetenland, the Polish Corridor and the Free City of Danzig (modern Gdańsk, Poland).[24] British policy-makers tended to exaggerate French power with the normally Francophile Sir Robert "Van" Vansittart, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office writing in 1931 that Britain was faced with an "unbearable" French domination of Europe, and what was needed was a revival of German power to counterbalance French power.[25] French economic and demographic weaknesses in the face of Germany's strengths such as the Reich's far larger population and economy together with the fact that much of France had been devastated by World War I while Germany had escaped mostly undamaged were little appreciated in Whitehall.

The European Situation, 1933–36

The diplomatic maneuvers

In March 1933, the German Defence Minister, General Werner von Blomberg had plans drawn up for remilitarization.[26] Blomberg starting in the fall of 1933 had a number of the para-military Landspolizei units in the Rhineland given secret military training and equipped with military weapons in order to prepare for remilitarization.[27] General Ludwig Beck's memo of March 1935 on the need for Germany to secure Lebensraum (living space) in Eastern Europe had accepted that remilitarization should take place as soon it was diplomatically possible.[26] In general, it was believed by German military, diplomatic and political elites that it would not be possible to remiltarize before 1937.[28]

The change of regime in Germany in 1933 did cause alarm in London, but there was considerable uncertainty about what Hitler’s long term intentions were. In August 1933, the chief of the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID), Royal Marine General Sir Maurice Hankey who served as the éminence grise of British defense and foreign policy, visited Germany, and wrote down his impressions of the “New Germany” in October 1933. Hankey’s report concluded with the words: “Are we still dealing with the Hitler of Mein Kampf, lulling his opponents to sleep with fair words to gain time to arm his people, and looking always to the day when he can throw off the mask and attack Poland? Or is it a new Hitler, who discovered the burden of responsible office, and wants to extricate himself, like many an earlier tyrant from the commitments of his irresponsible days? That is the riddle that has to be solved”.[29] This uncertainty over what Hitler’s ultimate intentions in foreign policy were was to color much of British policy towards Germany until 1939. British decision-makers could never quite decide if Hitler was merely seeking the acceptable goal (to the British) of revising Versailles or the unacceptable goal of seeking to dominate Europe. British policy towards Germany was a dual-track policy of seeking a "general settlement" with the Reich in which the "legitimate" German complaints about the Versailles treaty would be addressed in Germany's favor while at the same time pursuing rearmament to negotiate with Germany from a position of strength, to deter Hitler from choosing war as an option, and in a worse case scenario ensure that Britain was prepared if Hitler really did want to conquer Europe. In February 1934, a secret report by the Defence Requirements Committee identified Germany as the "ultimate potential enemy", which British rearmament was to be directed against.[30] Although the possibility of German bombing attacks against British cities increased the importance of having a friendly power on the other side of the English Channel, many British decision-makers were cool, if not downright hostile, towards the idea of the "continental commitment".[31] When British rearmament began in 1934, the Army received the lowest priority in terms of funding after the air force and the navy, in part to rule out the "continental commitment" as an option.[32] Increasingly, decision-makers came to favor the idea of "limited liability", under which if the "continental commitment" were to be made, Britain should only send the smallest possible expeditionary force to Europe, and reserve its main efforts towards the war in the air and on the sea.[33] Britain's refusal to make the "continental commitment" on the same scale as World War I caused tensions with the French, who believed that it would be impossible to defeat Germany without another large-scale "continental commitment", and deeply disliked the idea that they should do the bulk of the fighting on the land.

Starting in 1934, the French Foreign Minister Louis Barthou had decided to put an end to any potential German aggression by building a network of alliances intended to encircle Germany, and made overtures to the Soviet Union and Italy. Until 1933, the Soviet Union had supported German efforts to challenge the Versailles system, but the strident anti-communism of the National Socialist regime together with its claim for Lebensraum had led the Soviets to do a volte-face on the question of maintaining the Versailles system. In September 1933, the Soviet Union ended its secret support for German rearmament, which had started in 1921. Under the guise of collective security, the Soviet Foreign Commissar Maxim Litvinov started to praise the Versailles system, which until then the Soviet leaders had denounced as a capitalist plot to "enslave" Germany. Starting in the 1920s, Benito Mussolini had subsidized the right-wing Heimwehr ("Home Defense") movement in Austria, and after the ultra-conservative Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss had seized dictatorial power in March 1933, Austria had fallen within the Italian sphere of influence.[34] The terrorist campaign mounted by Austrian Nazis with the open support of Germany against the Dollfuss regime with the aim of overthrowing Dollfuss to achieve an Anschluss caused considerable tensions between Rome and Berlin.[34] Mussolini had warned Hitler several times that Austria was within the Italian sphere of influence, not the German, and to cease trying to overthrow his protégé Dollfuss. On 25 July 1934 there had occurred the July Putsch in Vienna that saw Dollfuss assassinated by the Austrian SS, and an announcement by the Austrian Nazis that the Anschluss was at hand. At the same time that Austrian Nazis attempted to seize power all over Austria, the SS Austrian Legion based in Bavaria began to attack frontier posts along the German-Austrian border in what looked like the beginning of an invasion. In response, Mussolini had mobilized the Italian Army, concentrated several divisions at the Brenner Pass, and warned Hitler that Italy would go to war with Germany if he tried to follow up the putsch by invading Austria.[34] Hitler was forced to beat a humiliating retreat as he had to disallow the Putsch he had ordered and he did not follow it up by invading Austria while the Austrian government crushed the Putsch by the Austrian Nazis.[34] After Barthou was assassinated on 9 October 1934, his work in trying to build anti-German alliances with the Soviet Union and Italy was continued by Pierre Laval. On 7 January 1935 during a summit in Rome, Laval essentially told Mussolini that he had a "free hand" in the Horn of Africa, and France would not oppose an Italian invasion of Ethiopia.[34] On 14 April 1935, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald of Great Britain, Premier Pierre Laval of France and Prime Minister Benito Mussolini met in Stresa to form the Stresa Front to oppose any further German violations of Versailles following the German statement in March 1935 that Germany would no longer abide by Parts V or VI of the Treaty of Versailles.[34] In the spring of 1935, joint staff talks had begun between France and Italy with the aim of forming an anti-German military alliance.[34] On 2 May 1935, Laval travelled to Moscow, where he a signed a treaty of alliance with Soviet Union.[35] At once, the German government began a violent press campaign against the Franco-Soviet pact, claiming it was a violation of Locarno that was an immense danger for the Reich.[35]

In his "peace speech" of May 21, 1935, Adolf Hitler stated "In particular, they [the Germans] will uphold and fulfill all obligations arising out of the Locarno Treaty, so long as the other parties are on their side ready to stand by that pact".[36] That line in Hitler's speech was written by his foreign minister, Baron Konstantin von Neurath who wished to reassure foreign leaders who felt threatened by Germany's denunciation in March 1935 of Part V of the Treaty of Versailles, which had disarmed Germany.[36] At the same time, Neurath wanted to provide an opening for the eventual remilitarization of the Rhineland, hence the conditional hedging of the promise to obey Locarno only as long as other powers did.[36] Hitler always took the line (at least in public) that Germany did not consider itself bound by the Diktat of Versailles, but that Germany would respect any treaty that it willingly signed such as Locarno, under which Germany had promised to keep the Rhineland demilitarized forever; hence Hitler always promised during his "peace speeches" to obey Locarno as opposed to Versailles.[37] Hitler would have remilitarized the Rhineland in March 1935 when he announced that Germany would no longer obey either Parts V or VI of Versailles, which had disarmed Germany, but since the Rhineland was covered by Locarno, its demilitarized status continued.[37] Furthermore, given that under Locarno, Britain and Italy were obliged to defend Germany if France should invade, from the German viewpoint, it made sense to continue to abide by Locarno, given the fear that France might march when Germany repudiated the disarmament clauses of Versailles in March 1935.[38]

The Abyssinia Crisis

On 7 June 1935, MacDonald resigned as British Prime Minister due to ailing health and was replaced by Stanley Baldwin of the Conservative Party; the leadership change did not affect British foreign policy in any meaningful way. On October 3, 1935, Italy invaded Ethiopia, and thus began the Abyssinia Crisis. Under strong pressure from a moralistic British public opinion, which was very much in favor of collective security, the British government took the lead in pressing the League of Nations for sanctions against Italy.[39] The decision of the British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin took a strong line in favor of collective security was mostly motivated by domestic politics. The British historian A. J. P. Taylor wrote:

"Cautious support for the League of Nations, though inadequate to restrain Mussolini, proved a triumphant manoeuvre in domestic politics. During the previous two years, the Labour Opposition had made all the running in foreign affairs. It caught the National government, both ways round, denouncing at one moment the failure to assert collective security, and at the next, the alleged sabotage of the Disarmament conference. Thus Labour hoped to win the votes both of the pacifists and of enthusiasts for the League. With casual adroitness, Baldwin turned the tables. "All sanctions short of war", which Hoare was supposed to be advocating at Geneva, presented Labour with a terrible dilemma. Should they demand stronger sanctions, with the risk of war, and thus lose the votes of the pacifists? Or should they denounce the League as a dangerous sham, and thus lose the votes of the enthusiasts for it? After fierce debate, Labour decided to do both, and the inevitable result followed. In November 1935 there was a general election...The National government was returned with a majority of nearly two hundred and fifty".[40]

Having just won an election on 14 November 1935 on the platform of upholding collective security, the Baldwin government pressed very strongly for sanctions against Italy for invading Ethiopia. The League Assembly voted for a British motion to impose sanctions on Italy with immediate effect on 18 November 1935.

The British line that collective security must be upheld with regard to Ethiopia caused considerable tensions between Paris and London, with the French taking the viewpoint that Hitler, not Mussolini, was the real danger to the peace, and that if the price of continuing Stresa Front was accepting the conquest of Ethiopia, it was worth paying.[39] Weinberg wrote:

"The French were amazed at the enthusiasm with which the British public endorsed in Africa the very principle of collective security that they had hitherto rejected with such emphasis in Europe. The nation that had been unwilling to accept responsibility for the integrity of the Eastern European allies of France suddenly seemed eager to support Ethiopia."[39]

The British historian Correlli Barnett wrote for Laval: "...all that really mattered was Nazi Germany. His eyes were on the demilitarised zone of the Rhineland; his thoughts on the Locarno guarantees. To estrange Italy, one of the Locarno powers, over such a question as Abyssinia did not appeal to Laval's Auvergnat peasant mind".[41] With Paris and London openly at loggerheads over the correct response to Italian invasion of Ethiopia, to say nothing of the very public rift between Rome and London, an opening was seen in Germany for remilitarization of the Rhineland.[39] The Anglo-Italian dispute placed the French in an uncomfortable position. On one hand, Britain's repeated refusal to make the "continental commitment" increased the value to the French of Italy as the only other nation in Western Europe capable of fielding a large army against Germany.[42] But on the other hand, the British economy was far larger than the Italian economy, which thus meant from the long-term French perspective, Britain was a much better ally as Britain had vastly more economic staying power than Italy for what was assumed would be another guerre de la longue durée ("war of the long duration", i.e. a long war against Germany).[42] The American historian Zach Shore wrote that: "...French leaders found themselves in the awkward position of seeking the military co-operation of two incompatible allies. Since Italy and Britain had clashing interests in the Mediterranean, France could not ally with one without alienating the other".[42] To avoid a total rupture with Britain, France did not use its veto power as a member of the League Council, and instead voted for the sanctions. But Laval did use the threat of a French veto to water down the sanctions, and to have such items such as oil and coal, which might have crippled Italy, removed from the sanctions list.[43] Nonetheless, Mussolini felt betrayed by his French friends, and next to Britain, France was the nation that he was most angry with for the sanctions. Despite all of Mussolini's outrage about the sanctions, they were largely ineffective. The United States and Germany-both of which were not members of the League-chose not to abide by the sanctions, and as result, American and German businesses supplied Italy with all of the goods that League had placed on the sanctions list, making the sanctions more of an annoyance than a problem for the Italians.[44]

Italian cryptographers had broken the British naval and diplomatic codes in the early 1930s; consequently, Mussolini knew very well that although Britain might threaten war through such moves like reinforcing the Mediterranean Fleet in September 1935, the British had already decided in advance that they would never go to war for Ethiopia.[45] Armed with this knowledge, Mussolini felt free to engage in all sorts of wild threats of war against Britain from late 1935 onwards, declaring at one point that he rather see the entire world "go up in a blaze" than stop his invasion of Ethiopia.[46] Mussolini's frequent threats to destroy the British Empire if the British continued to oppose his Ethiopian war had created the impression in late 1935-early 1936 that Britain and Italy were on the verge of war.

In late 1935, Neurath started rumours that Germany was considering remilitarizing the Rhineland in response to the Franco-Soviet pact of May 1935, which Neurath insisted was a violation of Locarno that menaced Germany.[36] At the same time, Neurath ordered German diplomats to start drawing up legal briefs justifying remilitarization of the Rhineland under the grounds that the Franco-Soviet pact violated Locarno.[36] In doing so, Neurath was acting without orders from Hitler, but in the expectation that time was ripe for remilitarization due to the crisis in Anglo-Italian relations caused by the Italo-Ethiopian War.[36] To resolve the Abyssinia Crisis, Robert Vansittart, the Permanent Undersecretary at the British Foreign Office proposed to the Foreign Secretary Samuel Hoare what came to be known as the Hoare–Laval plan under which half of Ethiopia would be given to Italy with the rest nominally independent under the Emperor Haile Selassie. Vansittart who was a passionate Francophile and an equally ardent Germanophobe saw Germany as the real danger, and wanted to sacrifice Ethiopia for the sake of maintaining the Stresa Front.[47][48] Vansittart had a powerful ally in Hankey, a proponent of realpolitik who saw the entire idea of imposing sanctions on Italy as so much folly.[49] Persuaded of the merits of Vansittart's approach, Hoare travelled to Paris to meet with Laval, who agreed to the plan. However, Alexis St. Leger, the General Secretary at the Quai d'Orsay-who unusually amongst the generally pro-Italian French officials, happened to have a visceral dislike of Fascist Italy-and he decided to sabotage the Hoare-Laval plan by leaking it to the French press.[50] St. Leger was by all accounts a "rather strange" character who sometimes chose to undercut policy initiatives that he disapproved of.[51] The eccentric St. Leger was especially noted for his obsession with writing long erotic poems celebrating the beauty and sensuality of women and the joys of sex, on which he spent a disproportionate amount of time on (St. Leger was however awarded a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1960 for his poetry). In a strange asymmetricity, the Francophile Vansittart at the Foreign Office was in favor the French approach that it was worth letting Italy conquer Ethiopia to continue the Stresa Front while the Anglophile St. Leger at the Quai d'Orsay was in favor of the British approach of upholding collective security, even at the risk of damaging the Stresa Front. When the news of the Hoare-Laval plan to essentially reward Mussolini reached Britain, it caused such an uproar that Hoare had to resign in disgrace (to be replaced by Anthony Eden) and the newly elected Baldwin government was almost toppled by a backbenchers' revolt. Baldwin lied to the House of Commons by claiming quite falsely that the cabinet was unaware of the Hoare-Laval plan, and that Hoare was a rogue minister acting on his own. In France, public opinion was just as outraged by the Hoare-Laval plan as British public opinion was. Laval's policy of internal devaluation of forcing deflation on the French economy in order to increase French exports to combat the Great Depression had already made him extremely unpopular, and the Hoare-Laval plan further damaged his reputation. The Chamber of Deputies debated the plan on 27 and 28 December, the Popular Front condemned it, with Léon Blum telling Laval: "You have tried to give and to keep. You wanted to have your cake and eat it. You cancelled your words by your deeds and your deeds by your words. You have debased everything by fixing, intrigue and slickness...Not sensitive enough to the importance of great moral issues, you have reduced everything to the level of your petty methods".[52] Yvon Delbos declared: "Your plan is dead and buried. From its failure, which is as total as possible, you could have – but you have not – drawn a personal conclusion. Two lessons emerge. The first is that you were in a dead end because you upset everyone without satisfying Italy. The second is that we must return to the spirit of the Covenant [of the League of Nations] by preserving agreement with the nations gathered at Geneva".[53] Paul Reynaud attacked the government for aiding Hitler by ruining the Anglo-French alliance.[53]

Mussolini for his part rejected the Hoare-Laval plan, saying he wanted to subject all of Ethiopia, not just half. Following the fiasco of the Hoare-Laval plan, the British government resumed its previous policy of imposing sanctions against Italy in a half-hearted way, which in turn imposed serious strains on relations with both Paris and especially Rome. Given the provocative Italian attitude, Britain wanted to begin staff talks with France for a possible war with Italy.[54] On 13 December 1935, Neurath told the British ambassador Sir Eric Phipps that Berlin regarded any Anglo-French staff talks without Germany-even if directed only against Italy-as a violation of Locarno that would force Germany to remilitarize the Rhineland.[54] Through Italo-German relations were quite unfriendly in 1935, Germany had been an outspoken supporter of the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, and offered Mussolini a benevolent neutrality.[55] Under the banner of white supremacy and fascism, Hitler came out strongly for the Italian invasion, and he made a point of shipping the Italians various raw materials and weapons, which the League of Nations sanctions had forbidden Italy.[56] Hitler's support for the Italian aggression won him much goodwill in Rome.[56] By contrast, Laval's pro-Italian intrigues and his efforts to sabotage the British-led effort to impose sanctions on Italy created a lasting climate of distrust between the British and the French.[57]

In the fall of 1935, a serious economic crisis gripped Germany, with inflation rapidly rising, currency reserves collapsing, living standards falling, well over half of the German people living below the poverty line, and most damaging of all to the Nazi regime's popularity, there were alarming shortages of food.[58] After experiencing an upsurge in 1933 and 1934, the German economy had fallen back into depression in 1935 mostly because the Nazi regime gave a priority to importing raw materials needed for rearmament over food imports (Germany had more people than it was capable of feeding) while at the same time refusing for reasons of prestige to consider devaluation of the Reichmark.[59] It was common in the fall of 1935 for people to speak of the "food crisis" (Ernährungskrise) as queues at food shops become longer and longer.[58] By January 1936, the Berlin police were reporting that "a shockingly high percentage of the population in Berlin" were "directly negative towards the State and the Movement".[60] The same report mentioned that in recent months there had been a huge increase in the number of pamphlets calling for the overthrow of the Nazi regime that had been issued by activists from the underground KPD.[60] In such a climate, Hitler was looking for a quick and easy foreign policy triumph to distract attention from the economic crisis.[61] Furthermore, in January 1936 in response to the Abyssinia Crisis, it was announced that the League of Nations was considering applying oil sanctions against Italy (which possessed no oil), a step that Mussolini had always said would lead to Italy going to war against any nation that voted at the League Council for oil sanctions.[62] Given Mussolini's open threats to attack any nation that voted for oil sanctions together with strong pressure from British public for the British government to vote for oil sanctions, Britain had deployed the majority of its military to the Mediterranean, and thus far from Germany.[62] As the news spread that Italian forces were committing widespread atrocities in Ethiopia, such as the massacres of civilians and the frequent use of chemical warfare against defenseless Ethiopian civilians, British public opinion started to press their government to do more with regards to sanctions against Italy. Such was the brutality of the Italian forces that between 1936–41 during anti-guerrilla operations to "pacify" Ethiopia that the Italians killed about 7% of Ethiopia's population.[63] Though the British had decided not to go to war with Italy, it was very clear that Mussolini was enraged at Britain as the nation most responsible for the League of Nations sanctions imposed on Italy. In such a context, within Whitehall fear started to grow that Mussolini would commit a reckless "mad dog act" like trying to destroy the British Mediterranean Fleet as he had threatened to do several times, and hence deployed the majority of British military power to the Mediterranean to guard against a possible war with Italy.[64] When the French Admiral Jean Decoux told the First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Ernle Chatfield that war with Italy was unlikely, Chatfield replied: "With dictators you never can tell. No one can say for sure that Mr. Mussolini will not take some serious decisions someday".[43]

German remilitarization

Neurath and secret intelligence

The British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden anticipated that by 1940 Germany might be persuaded to return to the League of Nations, accept arms limitations, and renounce her territorial claims in Europe in exchange for remilitarization of the Rhineland, return of the former German African colonies and German "economic priority along the Danube"[65] The Foreign Office's Ralph Wigram advised that Germany should be permitted to remilitarise the Rhineland in exchange for an "air pact" outlawing bombing and a German promise not to use force to change their borders. However, 'Wigram did not succeed in convincing his colleagues or cabinet ministers'.[66] Eden's goal has been defined as that of a "general settlement", which sought "a return to the normality of the twenties and the creation of conditions in which Hitler could behave like Stresemann." (Gustav Stresemann German chancellor, foreign minister and democrat during the Weimar Republic)[67] On 16 January 1936, the French Premier Pierre Laval submitted the Franco-Soviet Pact to the Chamber of Deputies for ratification.[68] In January 1936, during his visit to London to attend the funeral of King George V, Neurath told Eden: "If, however, the other signatories or guarantors of the Locarno Pact should conclude bilateral agreements contrary to the spirit of Locarno Pact, we should be compelled to reconsider our attitude."[69] Eden's response to Neurath's veiled threat that Germany would remilitarize the Rhineland if the French National Assembly ratified the Franco-Soviet pact convinced him that if Germany remilitarized, then Britain would take Germany's side against France.[69] There was a clause in the Locarno treaty calling for binding international arbitration if the one of the signatory powers signed a treaty that the other powers considered to be incompatible with Locarno.[70] Both Neurath and his State Secretary Prince Bernhard von Bülow professed to every foreign diplomat with whom they spoke to that the Franco-Soviet Pact was a violation of Locarno, but at the same time both strongly advised Hitler not to seek international arbitration to see if Franco-Soviet pact really was a violation of Locarno.[70] Seeking international arbitration was a "lose-lose" situation for Germany: on the one hand, if it were ruled that the Franco-Soviet pact was incompatible with Locarno, then the French would have to abandon the pact, thereby depriving Germany of an excuse to remilitarize; on the other hand, if it were ruled that Franco-Soviet pact was compatible with Locarno, Germany would likewise have no excuse for remilitarization.[70] Although Neurath indicated several times in press conferences in early 1936 that Germany was planning on using the arbitration clause in Locarno, in order to help convince public opinion abroad that the Franco-Soviet pact was a violation of Locarno, the German government never invoked the arbitration clause.[70]

At the same time, Neurath received an intelligence report on 10 January 1936 from Gottfried Aschmann, the Chief of the Auswärtiges Amt's Press Division, who during a visit to Paris in early January 1936 had talked to a minor French politician named Jean Montiny who was a close friend of Premier Laval, who had frankly mentioned that France's economic problems had retarded French military modernization and that France would do nothing if Germany remilitarized the Rhineland.[71] According to Aschmann, Montiny had said:

"In Paris one begins to realise that Germany wants to overturn the current status, be it through real concerns or fictitious ones. One longer sees it as an absolute casus belli, as in the recent past, but the politicians believe a judgement on this matter must come first and foremost from the Army General Staff. There has naturally been discussion over the consequences, but to date, no consensus has been reached. One group believes that given the extraordinary advances in military motorization, the entire question is less a matter of practical military significance than of moral value to the German self-image. Another group in the General Staff are of the opinion that remilitarization could only be accepted if a full reorganization of the border defense system were to take place and above all if the defensive garrisons were promptly improved. As the situation stands today, one is neither ready nor willingly unhesitating to go to war over the eventuality of a German reoccupation (the last sentence was underlined by Neurath)."[72]

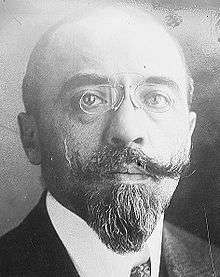

Aschmann did not explicitly state this, but he strongly implied that he had bribed Montiny into talking so frankly. Neurath did not pass on Aschmann's report to Hitler, but he placed a high value upon it.[72] Neurath was seeking to improve his position within the Nazi regime; by repeatedly assuring Hitler during the Rhineland crisis that the French would do nothing without telling Hitler the source of his self-assurance, Neurath came across as a diplomat blessed with an uncanny intuition, something that improved his standing with Hitler.[73] Traditionally in Germany the conduct of foreign policy had been the work of the Auswärtiges Amt (Foreign Office), but starting in 1933 Neurath had been faced with the threat of Nazi "interlopers in diplomacy" as various NSDAP agencies started to conduct their own foreign policies independent of and often against the Auswärtiges Amt.[74] The most serious of the "interlopers in diplomacy" was the Dienststelle Ribbentrop, a sort of alternative foreign ministry loosely linked to the NSDAP headed by Joachim von Ribbentrop that aggressively sought to undercut the work of the Auswärtiges Amt at every turn.[75] Further exacerbating the rivalry between the Dienststelle Ribbentrop and the Auswärtiges Amt was the fact that Neurath and Ribbentrop utterly hated one another, with Ribbentrop making no secret of his belief that he would be a much better foreign minister than Neurath, whereas Neurath viewed Ribbentrop as a hopelessly inept amateur diplomat meddling in matters that did not concern him.[76] In this environment, Baron von Neurath was determined to prove to Hitler that he, a professional diplomat of the old school who had joined the Auswärtiges Amt in 1901 was the man best qualified to carry out the Reich's foreign policy, and thereby prove that the Auswärtiges Amt should be allowed to conduct foreign policy alone as traditionally had been the case rather than the Nazi "interlopers in diplomacy".[77]

The decision to remilitarize

During January 1936, the German Chancellor and Führer Adolf Hitler decided to reoccupy the Rhineland. Originally Hitler had planned to remilitarize the Rhineland in 1937, but chose in early 1936 to move re-militarization forward by a year for several reasons, namely: the ratification by the French National Assembly of the Franco-Soviet pact of 1935 allowed him to present his coup both at home and abroad as a defensive move against Franco-Soviet "encirclement"; the expectation that France would be better armed in 1937; the government in Paris had just fallen and a caretaker government was in charge; economic problems at home required a foreign policy success to restore the regime's popularity; the Italo-Ethiopian War, which had set Britain against Italy, had effectively broken up the Stresa Front; and apparently because Hitler simply did not feel like waiting an extra year.[78][79] In his biography of Hitler, the British historian Sir Ian Kershaw argued that the primary reasons for the decision to remilitarize in 1936 as opposed to 1937 were Hitler's preference for dramatic unilateral coups to obtain what could easily be achieved via quiet talks, and Hitler's need for a foreign policy triumph to distract public attention from the major economic crisis that was gripping Germany in 1935–36.[80]

During a meeting between Prince Bernhard von Bülow, the State Secretary at the Auswärtiges Amt (who is not to be confused with his more famous uncle Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow) and the French Ambassador André François-Poncet on 13 January 1936, where Bülow handed François-Poncet yet another note protesting against the Franco-Soviet pact, François-Poncet accused Bülow to his face of seeking any excuse, no matter how bizarre, strange or implausible to send troops back into the Rhineland.[81] On 15 January 1936, a top-secret NKVD report was sent to Joseph Stalin entitled "Summary of Military and Political Intelligence on Germany", which reported – based on statements from various diplomats in the Auswärtiges Amt – that Germany was planning on remilitarizing the Rhineland in the near-future.[82] The same summary quoted Bülow as saying that if Britain and France made any sort of agreement concerning military co-operation that did not involve Germany: "We would view this as a violation of Locarno, and if we are not dragged into participating in negotiations, we will not consider ourselves bound by Locarno obligations concerning the preservation of the Rhine demilitarized zone".[83] The Soviet report warning of German plans for remilitarization was not passed on to either the British or French governments.[83]

On 17 January 1936 Benito Mussolini – who was angry about the League of Nations sanctions applied against his country for aggression against Ethiopia – told the German Ambassador in Rome, Ulrich von Hassell, that he wanted to see an Austro-German agreement "which would in practice bring Austria into Germany's wake, so that she could pursue no other foreign policy than one parallel with Germany. If Austria, as a formally independent state, were thus in practice to become a German satellite, he would have no objection".[84][85] By recognizing Austria was within the German sphere of influence, Mussolini had removed the principal problem in Italo-German relations.[85] Italo-German relations had been quite bad since mid-1933, and especially since the July Putsch of 1934, so Mussolini's remarks to Hassell in early 1936 indicating that he wanted a rapprochement with Germany were considered extremely significant in Berlin.[84] In another meeting, Mussolini told Hassell that he regarded the Stresa Front of 1935 as "dead", and that Italy would do nothing to uphold Locarno should Germany violate it.[84] Initially German officials did not believe in Mussolini's desire for a rapprochement, but after Hitler sent Hans Frank on a secret visit to Rome carrying a message from the Führer about Germany's support for Italy's actions in the conquest of Ethiopia, Italo-German relations improved markedly.[84] On 24 January, the very unpopular Laval resigned as premier rather than be defeated on a motion of no-confidence in the National Assembly as the Radical Socialists decided to join the left-wing Popular Front, thereby ensuring an anti-Laval majority in the Chamber of Deputies.[86] A caretaker government was formed in Paris led by Albert Sarraut until new elections could be held. The Sarraut cabinet was a mixture of men of the right like Georges Mandel, the center like Georges Bonnet and the left like Joseph Paul-Boncour which made it almost impossible for the cabinet to make decisions.[87] Immediately, the Sarraut government came into conflict with Britain as Eden started to press the League for oil sanctions against Italy, something that the French were completely opposed to, and threatened to veto.[88]

On 11 February 1936, the new French Premier Albert Sarraut affirmed that his government would work for the ratification of the Franco-Soviet pact.[68] On February 12, 1936, Hitler met with Neurath and his Ambassador-at-Large Joachim von Ribbentrop to ask their opinion of the likely foreign reaction to remilitarization.[69] Neurath supported remiltarization, but argued that Germany should negotiate more before doing so whereas Ribbentrop argued for unilateral remilitarization at once.[89] Ribbentrop told Hitler that if France went to war in response to German remiltarization, then Britain would go to war with France, an assessement of the situation with which Neurath did not agree, but one that encouraged Hitler to proceed with remiltarization.[89]

On the 12th of February Hitler informed his War Minister, Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg, of his intentions and asked the head of the Army, General Werner von Fritsch, how long it would take to transport a few infantry battalions and an artillery battery into the Rhineland. Fritsch answered that it would take three days organization but he was in favour of negotiation, as he believed that the German Army was in no state for armed combat with the French Army.[90] The Chief of the General Staff, General Ludwig Beck warned Hitler that the German Army would be unable to successfully defend Germany against a possible retaliatory French attack.[91] Hitler reassured Fritsch that he would withdraw his forces if there were a French countermove. Weinberg wrote that:

"German military plans provided for small German units to move into the Rhineland, joining the local militarized police (Landespolizei) and staging a fighting withdrawal if there were a military counter-action from the West. The story that the Germans had orders to withdraw if France moved against them is partially correct, but essentially misleading; the withdrawal was to be a tactical defensive move, not a return to the earlier position. The possibility of a war was thus accepted by Hitler, but he clearly did not think the contingency very likely."[92]

The operation was codenamed Winter Exercise. Unknown to Hitler, on 14 February Eden had written to the Quai d'Orsay stating that Britain and France should "enter betimes into negotiations...for the surrender on conditions of our rights in the zone while such surrender still has got a bargaining value".[93] Eden wrote to the British cabinet that the end of the demilitarized zone would "not merely change local military values, but is likely to lead to far-reaching political repercussions of a kind which will further weaken France's influence in Central and Eastern Europe".[94] In February 1936, the Deuxième Bureau started to submit reports suggesting that Germany was planning on sending troops into the Rhineland in the very near-future.[95] Because François-Poncet's reports from Berlin indicated that the German economic situation was quite precarious, it was felt in Paris that sanctions against Germany could be quite devastating, and might even lead to the collapse of the Nazi regime.[96]

Along with Ribbentrop and Neurath, Hitler discussed the planned remilitarization in detail with War Minister General Werner von Blomberg, Chief of General Staff General Ludwig Beck, Hermann Göring, Army Commander-in-Chief General Werner von Fritsch and Ulrich von Hassell.[97] Ribbentrop and Blomberg were in favor; Beck and Fritsch were opposed and Neurath and Hassell were supportive, but argued that there was no real need to act now as quiet diplomacy would soon ensure remilitarization.[98] That Hitler was in close and regular contact with Hassell, the ambassador to Italy all through February and early March, showed how much importance Hitler attached to Italy.[98] Of the three leaders of the Stresa front, Mussolini was easily the one Hitler most respected, and so Hitler viewed Italy as the key, taking the view that if Mussolini decided to oppose the remilitarization, then Britain and France would follow.[68] Not withstanding Mussolini's remarks in January, Hitler was still not convinced of Italian support, and ordered Hassell to find out Mussolini's attitude.[99] On 22 February, Hassell wrote in his diary that the pending ratification of the Franco-Soviet pact was just a pretext, writing: "it was quite clear that he [Hitler] really wanted the ratification to use as a platform for his action".[100] That same day, Hassell held a meeting with Mussolini, where Il Duce stated if oil sanctions were applied against Italy, he would "make Locarno disappear of its own accord", and that anyhow Italy would not act if German troops were to enter the Rhineland.[101] The Polish Ambassador to Germany Józef Lipski reported about Göring that:

"Göring was visibly terrified of the Chancellor's decision to remilitarise the Rhineland, and he didn't conceal that it was taken against the Reichswehr's advice. I had several talks with him then. I found him in an utmost state of agitation, and this was just at the time of the London conference. He openly gave me to understand that Hitler had taken this extremely risky step by his own decision, in contradiction of the advice of his own generals. Göring went so far in his declaration as to say literally that, if France entered upon a war with Germany, the Reich would defend itself to the last man, but if Poland joined France, then Germany's situation would be catastrophic. In a broken voice, Göring said he saw many misfortunes befalling the German nation, bereaved mothers and wives...Göring's breakdown during the Rhineland period made me wonder about his psychological stamina. I thought this might be due to his physical condition, since he was using narcotics."[102]

At the same time, Neurath started preparing elaborate documents justifying remilitarization as a response forced on Germany by the Franco-Soviet pact, and advised Hitler to keep the number of troops sent into the Rhineland very small so to allow the Germans to claim that they had not committed a "flagrant violation" of Locarno (both Britain and Italy were only committed to offering a military response to a "flagrant violation").[103] In the statement justifying remilitarization that Neurath prepared for the foreign press, the German move was portrayed as something forced on a reluctant Germany by ratification of the Franco-Soviet pact, and strongly hinted that Germany would return to the League of Nations if remilitarization was accepted.[103] After meeting with Hitler on 18 February, Baron von Neurath expressed the viewpoint "for Hitler in the first instance domestic motives were decisive".[104]

At the same time that Frank was visiting Rome, Göring had been dispatched to Warsaw to meet the Polish Foreign Minister Colonel Józef Beck and to ask the Poles to remain neutral if France decided on war in response to the remilitarization of the Rhineland.[105] Colonel Beck believed that the French would do nothing if Germany remilitarized the Rhineland, and thus could assure those in the Polish government who wished for Poland to stay close to its traditional ally France that Poland would act if France did while at the same time telling Göring that he wanted closer German-Polish relations and would do nothing in the event of remilitarization.[105]

On 13 February 1936 during a meeting with Prince Bismarck of the German Embassy in London, Ralph Wigram, the head of the Central Department of the British Foreign Office stated that the British government (whose Prime Minister from 1935 to 1937 was Stanley Baldwin) wanted a "working agreement" on an air pact that would outlaw bombing, and that Britain would consider revising Versailles and Locarno in Germany's favor for an air pact.[69] Prince Bismarck reported to Berlin that Wigram had hinted quite strongly that the "things" that Britain were willing to consider revising included remilitarization.[69] On 22 February 1936 Mussolini, who was still angry about the League of Nations sanctions applied against his country for aggression against Ethiopia told von Hassell that Italy would not honour Locarno if Germany were to remilitarize the Rhineland.[106] Even if Mussolini had wanted to honour Locarno, practical problems would have arisen as the bulk of the Italian Army was at that time engaged in the conquest of Ethiopia, and as there is no common Italo-German frontier.

Historians debate the relation between Hitler's decision to remilitarize the Rhineland in 1936 and his broad long-term goals. Those historians who favour an "intentionist" interpretation of German foreign policy such as Klaus Hildebrand and the late Andreas Hillgruber see the Rhineland remilitarization as only one "stage" of Hitler's stufenplan (stage by stage plan) for world conquest. Those historians who take a "functionist" interpretation see the Rhineland remilitarization more as ad hoc, improvised response on the part of Hitler to the economic crisis of 1936 as a cheap and easy way of restoring the regime's popularity. The British Marxist historian Timothy Mason famously argued that Hitler's foreign policy was driven by domestic needs related to a failing economy, and that it was economic problems at home as opposed to Hitler's "will" or "intentions" that drove Nazi foreign policy from 1936 onwards, which ultimately degenerated into a “barbaric variant of social imperialism", which led to a "flight into war" in 1939.[107][108] As Hildebrand himself has noted, these interpretations are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Hildebrand has argued that although Hitler did have a "programme" for world domination, the way in which Hitler attempted to execute his "programme" was highly improvised and much subject to structural factors both on the international stage and domestically that were often not under Hitler's control.[109] On February 26 the French National Assembly ratified the Franco-Soviet pact. On February 27, Hitler had lunch with Hermann Göring and Joseph Goebbels to discuss the planned remilitarization, with Goebbels writing in his diary afterwards: "Still somewhat too early".[110] On February 29 an interview Hitler had on February 21 with the French fascist and journalist Bertrand de Jouvenel was published in the newspaper Paris-Midi.[111] During his interview with a clearly admiring de Jouvenel, Hitler professed himself a man of peace who desperately wanted friendship with France and blamed all of the problems in Franco-German relations on the French who for some strange reason were trying to "encircle" Germany via the Franco-Soviet pact, despite the evident fact that the Fuhrer was not seeking to threaten France.[111] Hitler's interview with de Jouvenel was intended to influence French public opinion into believing that it was their government that was responsible for the remilitarization. Only on March 1 did Hitler finally make up his mind to proceed.[112] A further factor in Hitler's decision was that the sanctions committee of the League was due to start discussing possible oil sanctions against Italy on 2 March, something that was likely to lead the diplomats of Europe to be focused on the Abyssinia Crisis at the expense of everything else.[113]

The Wehrmacht marches

Not long after dawn on March 7, 1936, nineteen German infantry battalions and a handful of planes entered the Rhineland. By doing so, Germany violated Articles 42 and 43 of the Treaty of Versailles and Articles 1 and 2 of the Treaty of Locarno.[114] They reached the river Rhine by 11:00 a.m. and then three battalions crossed to the west bank of the Rhine. At the same time, Baron von Neurath summoned the Italian ambassador Count Bernardo Attolico, the British ambassador Sir Eric Phipps and the French ambassador André François-Poncet to the Wilhelmstrasse to hand them notes accusing France of violating Locarno by ratifying the Franco-Soviet pact, and announcing that as such Germany had decided to renounce Locarno and remilitarize the Rhineland.[115]

When German reconnaissance learned that thousands of French soldiers were congregating on the Franco-German border, General Blomberg begged Hitler to evacuate the German forces. Under Blomberg's influence, Hitler nearly ordered the German troops to withdraw, but was then persuaded by the resolutely calm Neurath to continue with Operation Winter Exercise.[116] Following Neurath's advice, Hitler inquired whether the French forces had actually crossed the border and when informed that they had not, he assured Blomberg that Germany would wait until this happened.[117] In marked contrast to Blomberg who was highly nervous during Operation Winter Exercise, Neurath stayed calm and very much urged Hitler to stay the course.[118]

The Rhineland coup is often seen as the moment when Hitler could have been stopped with very little effort; the German forces involved in the move were small, compared to the much larger, and at the time more powerful, French military. The American journalist William L. Shirer wrote if the French had marched into the Rhineland,

that almost certainly would have been the end of Hitler, after which history might have taken quite a different and brighter turn than it did, for the dictator could never have survived such a fiasco...France's failure to repel the Wehrmacht battalions and Britain's failure to back her in what would have been nothing more than a police action was a disaster for the West from which sprang all the later ones of even greater magnitude. In March 1936 the two Western democracies, were given their last chance to halt, without the risk of a serious war, the rise of a militarized, aggressive, totalitarian Germany and, in, fact-as we have seen Hitler admitting-bring the Nazi dictator and his regime tumbling down. They let the chance slip.[119]

A German officer assigned to the Bendlerstrasse during the crisis told H. R. Knickerbocker during the Spanish Civil War: "I can tell you that for five days and five nights not one of us closed an eye. We knew that if the French marched, we were done. We had no fortifications, and no army to match the French. If the French had even mobilized, we should have been compelled to retire." The general staff, the officer said, considered Hitler's action suicidal.[120] General Heinz Guderian, a German general interviewed by French officers after the Second World War, claimed: "If you French had intervened in the Rhineland in 1936 we should have been sunk and Hitler would have fallen."[121]

That Hitler faced serious opposition gains apparent weight from the fact that Ludwig Beck and Werner von Fritsch did indeed become opponents of Hitler but according to the American historian Ernest May there is not a scrap of evidence for this at this stage.[122] May wrote that the German Army officer corps was all for remilitarizing the Rhineland, and only the question of timing of such a move divided them from Hitler.[123] May further noted that there is no evidence that the German Army was planning on overthrowing Hitler if he had been forced to order a withdraw from the Rhineland, and the fact that Mussolini utterly humiliated Hitler during the July Putsch in 1934 by forcing Germany to climb-down on Austria without leading to the slightest effort on the part of the Reichswehr to overthrow Hitler must cast further doubt on the thesis that Hitler would have been toppled if only he been forced to withdraw from the Rhineland.[123]

Writing about relations between Hitler and his generals in early 1936, the American historian J.T. Emerson declared: "In fact, at no time during the twelve-year existence of the Third Reich did Hitler enjoy more amicable relations with his generals than in 1935 and 1936. During these years, there was nothing like an organized military resistance to party politics".[124] Later on in World War II, despite the increasing desperate situation of Germany from 1942 onwards and a whole series of humiliating defeats, the overwhelming majority of the Wehrmacht stayed loyal to the Nazi regime and continued to fight hard for that regime right up to its destruction in 1945 (the only exception being the putsch of July 20, 1944, in which only a minority of the Wehrmacht rebelled while the majority remained loyal).[125] The willingness of the Wehrmacht to continue to fight and die hard for the National Socialist regime despite the fact Germany was clearly losing the war from 1943 onwards reflected the deep commitment of most of the Wehrmacht to National Socialism.[126]

Furthermore, the senior officers of the Wehrmacht were deeply corrupt men, who received huge bribes from Hitler in exchange for their loyalty.[127] In 1933, Hitler had created a slush fund known as Konto 5 run by Hans Lammers, which provided bribes to senior officers and civil servants in exchange for their loyalty to the National Socialist regime.[127] Given the intense devotion of the Wehrmacht to the National Socialist regime and its corrupt senior officers who never got quite enough in the way of bribes from Hitler, it is very unlikely that the Wehrmacht would have turned on their Fuhrer if the Wehrmacht were forced out of the Rhineland in 1936. Hitler himself later said:

The forty-eight hours after the march into the Rhineland were the most nerve-racking in my life. If the French had then marched into the Rhineland we would have had to withdraw with our tails between our legs, for the military resources at our disposal would have been wholly inadequate for even a moderate resistance.[128]

The British historian Ian Kershaw wrote that Hitler had conveniently forgotten his own orders for a fighting retreat if the French should march, and that Hitler was exaggerating here for effect the extent of the planned German retreat, in order to prove he was a leader blessed by "providence".[129]

Reactions

Germany

On 7 March 1936 Hitler announced before the Reichstag that the Rhineland had been remilitarized, and to blunt the danger of war, Hitler offered to return to the League of Nations, to sign an air pact to outlaw bombing as a way of war, and a non-aggression pact with France if the other powers agreed to accept the remilitarization.[112] In his address to the Reichstag, Hitler began with a lengthy denunciation of the Treaty of Versailles as unfair to Germany, claimed that he was a man of peace who wanted war with no-one, and argued that he was only seeking equality for Germany by peacefully overturning the unfair Treaty of Versailles.[130] Hitler claimed that it was unfair that because of Versailles a part of Germany should be demilitarized whereas in every other nation of the world a government could order its troops to anywhere within its borders, and claimed all he wanted was "equality" for Germany.[130] Even then, Hitler claimed that he would have been willing to accept the continued demilitarization of the Rhineland as Stresemann had promised at Locarno in 1925 as the price for peace, had it not been for the Franco-Soviet Pact of 1935, which he maintained was threatening to Germany and had left him with no other choice than to remilitarize the Rhineland.[130] With his eye on public opinion abroad, Hitler made a point of stressing that the remilitarization was not intended to threaten anyone else, but was instead only a defensive measure imposed on Germany by what he claimed were the menacing actions of France and the Soviet Union.[130] At least some people abroad accepted Hitler's claim that he been forced to take this step because of the Franco-Soviet pact. Former British Prime Minister David Lloyd-George stated in the House of Commons that Hitler's actions in the wake of the Franco-Soviet pact were fully justified, and he would have been a traitor to Germany if he had not protected his country.[131]

When German troops marched into Cologne, a vast cheering crowd formed spontaneously to greet the soldiers, throwing flowers onto the Wehrmacht while Catholic priests offered to bless the soldiers.[129] Cardinal Karl Joseph Schulte of Cologne held a Mass at Cologne Cathedral to celebrate and thank Hitler for "sending back our army".[130] In Germany, the news that the Rhineland had been remilitarized was greeted with wild celebrations all over the country; the British historian Sir Ian Kershaw wrote of March 1936 that: "People were besides themselves with delight...It was almost impossible not to be caught up in the infectious mood of joy".[132] Not until the victory over France in June 1940 was the Nazi regime to be as popular as it was in March 1936. Reports to the Sopade in the spring of 1936 mentioned that a great many erstwhile Social Democrats and opponents of the Nazis amongst the working class had nothing but approval of the remilitarization, and that many who had once been opposed to the Nazis under the Weimar Republic were now beginning to support them.[132] The conservative historian Gerhard Ritter, who was out of favor with the Nazi regime as a member of the Confessing Church and who witnessed the return of the German soldiers to the Rhineland first-hand wrote in a letter to his mother that for his children "who had never seen German soldiers from close up, this is one of the greatest experiences ever.... Truly a great and magnificent experience. May God grant that it does not lead to some international catastrophe".[133] In Hamburg, the ultra-nationalist, conservative housewife Luise Solmitz whose husband and daughter had recently lost their German citizenship under the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 as Mischlinge ("half-breeds") wrote in her diary after the remilitarization:

"I was totally overwhelmed by the events of this hour..overjoyed at the entry march of our soldiers, at the greatness of Hitler and the power of his speech, the force of this man. A few years ago, when demoralization ruled amongst us, we would not have dared contemplate such deeds. Again and again the Führer faces the world with a fait accompli. Along with the world, the individual holds his breath. Where is Hitler heading, what will be the end, the climax of this speech, what boldness, what surprise will there be? And then it comes, blow on blow, action is stated without fear of his own courage. That is so strengthening...That is the deep, unfathomable secret of the Führer's nature...And he is always lucky".[132]

To capitalize on the vast popularity of the remilitarization, Hitler called a referendum on 29 March 1936 in which the majority of German voters expressed their approval of the remilitarization.[132] During his campaign stops to ask for a yes vote, Hitler was greeted with huge crowds roaring their approval of his defiance of Versailles.[132] Kershaw wrote that the 99% ja (yes) vote in the referendum was improbably high, but it is clear that an overwhelming majority of voters did genuinely chose to vote yes when asked if they approved of the remilitarization.[134] The American journalist William L. Shirer wrote about the 1936 election:

"Nevertheless, this observer, who covered the "election" from one corner of the Reich to the other, has no doubt that the vote of approval for Hitler's coup was overwhelming. And why not? The junking of Versailles and the appearance of German soldiers marching again into what was, after all, German territory were things that almost all Germans naturally approved of. The No vote was given as 540, 211."[135]

In the aftermath of the remilitarization, the economic crisis which had so damaged the National Socialist regime's popularity was forgotten by almost all.[136] After the Rhineland triumph, Hitler's self-confidence surged to new heights, and those who knew well him stated that after March 1936 there was a real psychological change as Hitler was utterly convinced of his infallibility in a way that he not been before.[136]

France

Historians writing without benefit of access to the French archives (which were not opened until the mid-1970s) such as William L. Shirer in his books The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1960) and The Collapse of the Third Republic (1969) have claimed that France, although possessing at this time superior armed forces compared to Germany, including after a possible mobilization 100 infantry divisions, was psychologically unprepared to use force against Germany.[137] Shirer quoted the figure of France having 100 divisions compared to Germany's 19 battalions in the Rhineland.[138] France's actions during the Rhineland crisis have often used as support of the décadence thesis that during the interwar period the supposed decadence of the French way of life caused the French people to degenerate physically and morally to the point that the French were simply unable to stand up to Hitler, and the French in some way had it coming when they were defeated in 1940.[139] Shirer wrote that the French could have easily turned back the German battalions in the Rhineland had the French people not been "sinking into defeatism" in 1936.[115] Historians such as the American historian Stephen A. Schuker who have examined the relevant French primary sources have rejected Shirer's claims as the work of an amateur historian writing without access to the primary sources, and have found that a major paralyzing factor on French policy was the economic situation as opposed to Shirer's claim that the French were just too cowardly to stand up to Hitler.[140] France's top military official, General Maurice Gamelin, informed the French government that the only way to remove the Germans from the Rhineland was to mobilize the French Army, which would not only be unpopular, it would also cost the French treasury 30 million francs per day.[141] Gamelin assumed a worst-case scenario in which a French move into the Rhineland would spark an all-out Franco-German war, a case which required full mobilization. Gamelin's analysis was supported by the War Minister, General Louis Maurin who told the Cabinet that it was inconceivable that France could reverse the German remilitarization without full mobilization.[142] This was especially the case as the Deuxième Bureau had seriously exaggerated the number of German troops in the Rhineland, sending in a report to the French cabinet estimating that there were 295,000 German troops in the Rhineland.[129] The Deuxième Bureau had come up with this estimate by counting all of the SS, SA and Landespolizei formations in the Rhineland as regular troops, and so the French believed only by full mobilization would France have enough troops to expel the alleged 295,000 German troops from the Rhineland.[129] The real number was actually 3,000 German soldiers.[116] The French historian Jean-Baptiste Duroselle accused Gamelin of distorting what the Deuxième Bureau's intelligence in his report to the cabinet by converting the SS, SA and Landespolizei units into fully trained troops to provide a reason for inaction.[143] Neurath's (truthful) statement that Germany had only sent 19 battalions into the Rhineland was dismissed by Gamelin as a ruse to allow Germans to claim that they not committed a "flagrant violation" of Locarno in order to avoid having Locarno invoked against Germany, and that Hitler would never risk a war by sending such a small force into the Rhineland.

At the same time, in late 1935-early 1936 France was gripped by a financial crisis, with the French Treasury informing the government that sufficient cash reserves to maintain the value of the franc as currently pegged by the gold standard in regard to the U.S. dollar and the British pound no longer existed, and only a huge foreign loan on the money markets of London and New York could prevent the value of the franc from experiencing a disastrous downfall.[144] Because France was on the verge of elections scheduled for the spring of 1936, devaluation of the franc, which was viewed as abhorrent by large sections of French public opinion, was rejected by the caretaker government of Premier Albert Sarraut as politically unacceptable.[144] Investor fears of a war with Germany were not conducive to raising the necessary loans to stabilize the franc: the German remilitarization of the Rhineland, by sparking fears of war, worsened the French economic crisis by causing a massive cash flow out of France as worried investors shifted their savings towards what were felt to be safer foreign markets.[145] The fact that France had defaulted on its World War I debts in 1932 understandably led most investors to conclude if France should be involved in another war with Germany, the French would default again on their debts. On March 18, 1936 Wilfrid Baumgartner, the director of the Mouvement général des fonds (the French equivalent of a permanent under-secretary) reported to the government that France for all intents and purposes was bankrupt.[146] Only by desperate arm-twisting from the major French financial institutions did Baumgartner manage to obtain enough in the way of short-term loans to prevent France from defaulting on her debts and keeping the value of the franc from sliding too far, in March 1936.[146] Given the financial crisis, the French government feared that there were insufficient funds to cover the costs of mobilization, and that a full-blown war scare caused by mobilization would only exacerbate the financial crisis.[146] The American historian Zach Shore wrote that: "It was not lack of French will to fight in 1936 which permitted Hitler's coup, but rather France's lack of funds, military might, and therefore operational plans to counter German remilitarization."[147]

An additional issue for the French was the state of the Armée de l'Air.[148] The Deuxième Bureau reported that not only had the Luftwaffe developed considerably more advanced aircraft than what France possessed, but owing to the superior productivity of German industry and the considerably larger size of the German economy the Luftwaffe had a three to one advantage in fighters.[148] Problems with productivity within the French aircraft industry meant the French air force would have a great deal of trouble replacing their losses in the event of combat with the Luftwaffe.[148] Thus, it was believed by the French military elite that should war come, then the Luftwaffe would dominate the skies, and not only attack French troops marching into the Rhineland, but bomb French cities. Yet another problem for the French were the attitudes of the states of the cordon sanitaire.[149] Since 1919, it had accepted that France needed the alliance system in Eastern Europe to provide additional manpower (Germany's population was three times the size of France's) and to open up an eastern front against the Reich. Without the states of the cordon sanitaire, it was believed impossible for France to defeat Germany. Only Czechoslovakia indicated firmly that it would go to war with Germany if France marched into the Rhineland while Poland, Romania and Yugoslavia all indicated that they would only to go to war if German soldiers entered France.[149] French public opinion and newspapers were very hostile towards the German coup, but few called for war.[150] The majority of the French newspapers called for League of Nations sanctions to be imposed on the Reich to inflict such economically crippling costs as to force the German Army out of the Rhineland, and for France to build new and reinforce the existing alliances with the aim of preventing further German challenges to the international status quo.[150] One of the few newspapers to support Germany was the royalist L'Action Française which ran a banner headline reading: "The Republic Has Assassinated the Peace!", and went on to say that the German move was justified by the Franco-Soviet pact.[151] On the other ideological extreme, the Communists issued a statement calling for national unity against "those who would lead us to carnage" who were the "Laval clique" who were allegedly pushing for a war with Germany because war was supposedly good for capitalism.[152]