River Neckinger

The River Neckinger is a subterranean river that rises in Southwark and flows through London to St Saviour's Dock where it enters the River Thames. The river is now totally enclosed and runs underground.

Course

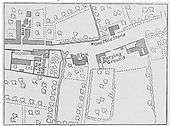

The river rises in what was formerly the marshy ground of St George's Fields, now Geraldine Mary Harmsworth Park, in Southwark,.[1] It follows the present day Brook Drive, passes by near to the Elephant and Castle,[2] then heads east towards the site of Lock Hospital.[3] This upper section of the river was known as Lock Stream.[3] It continues through the former grounds of Bermondsey Abbey,[4] today marked by Abbey Street,[2] before meeting the Thames at St Saviour's Dock.[3] The Neckinger divides the Thames riverside districts of Shad Thames to the west and the area historically known as Jacob's Island to the east.

History

Etymology

In the 17th century convicted pirates were hanged at the wharf where the Neckinger entered the Thames.[3] The name of the river is believed to derive from the term "devil's neckcloth", a slang term for the hangman's noose.[3] In London Past and Present, published in 1891, Henry B. Wheatley argued that there was 'much good evidence' that 'the 'Devil's Neckinger'... the ancient place of punishment and execution' was at the site of the 'Dead Tree public-house' on Jacob's Island.[5] Writing in The Inns of Old Southwark And Their Associations, in 1888, authors William Rendle and Philip Norman note that a place called Devol's Neckenger appears on a map in 1740 and, in the same location, in 1813, the Dead Tree inn.[6]

Canute's Trench

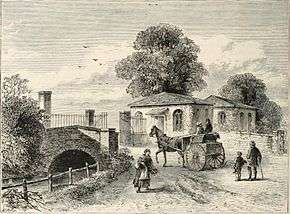

Historian Walter Besant states the Neckinger's early section, where it crosses the Kent Road, at Lock Bridge, was also known as Canute's Trench.[7] In May, 1016,[8] Danish Cnut the Great, who had invaded England, dug a trench through Southwark to allow his boats to avoid the heavily defended London Bridge.[9] In 1173, a channel following a similar course was used to drain the Thames to allowing building work on London Bridge.[10]

Middle Ages

In the 14th century, the crossing point of the Neckinger and the Old Kent Road was known as the wateryng of Seint Thomas, or St. Thomas-à-Watering, and was mentioned by Geoffrey Chaucer in The Canterbury Tales as the place where the pilgrims water their horses on their way to Thomas Becket's shrine.[11][12] In the Tudor period St. Thomas-à-Watering was also the location for public executions.[13]

In the 16th century, herbalist and botanist John Gerard wrote of the wild willow herb that 'It is found nigh the place of execution at St. Thomas a Watering; and by a style on a Thames bank near to the Devil's Neckerchief on the way to Redriffe.'[6]

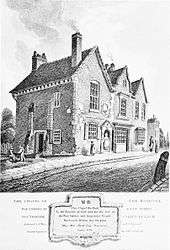

During the Middle Ages, the local religious house, Bermondsey Abbey, made use of the water of the Neckinger to power a Tide mill.[4] The mill's early name was Redriff,[14] also an early name for the present neighbouring district of Rotherhithe,[15][16] On 31 June 1536, the Abbey leased the mill to John Curlew,[17] but the Dissolution of the Monasteries saw it privately acquired.[14] At this time the Neckinger was navigable from the Thames up to the Abbey grounds.[18]

Local doctor, William Rendle, writing in Old Southwark And Its People, in 1878, describes a bridge on the Old Kent Road, dated to the time of Bermondsey Abbey, which was still visible as part of the sewer system in the 19th century. It was 'of a pointed arch of stone with six ribs, similar to the oldest part of the London Bridge and to those of Bow and Eltham. There are, however, no mouldings to the bridge; it was merely chamfered at the edges. Its date may be about the middle of the fifteenth century... The dimensions of the bridge are: width, 20 feet; span of arch, 9 feet.'[19]

In 1640, the City of London issued an order to 'make up and amend' the Lock Bridge as part of sewer works. According to Rendle the sewers were built up to adjoin the bridge at each side and it was a familiar landmark to 'sewer people' in the tunnels. During the 19th century improvements 'the ancient relic was not injured by the new works but necessarily covered up again.[19]

17th and 18th centuries

Private homes and businesses began to be built on the former Abbey grounds and the water supply of the Neckinger attracted tanners to its banks.[18] In the late 1700s competition for the river's water led to the tanners bringing a suit against the mill owner which was won on the argument of 'ancient usages of the district' which ensured the inhabitants had the right to a supply of tidal water.[18]

The Jacob's Island district was notoriously squalid from early Victorian times. It was described by Charles Dickens in 1838 as "the filthiest, the strangest, the most extraordinary of the many localities that are hidden in London",[20] and by the Morning Chronicle in 1849 as "The very capital of cholera" and "The Venice of drains". In Dickens' novel, Oliver Twist a branch of the Neckinger is given the name Folly Ditch and is the place where the book's Bill Sikes meets his death.[20][21]

In the 1790s Neckinger Mill was established to produce paper, which continued until 1805 when the site was sold to the leather manufacturers Bevingtons.[22] In 1838, the construction of a new line for the London and Greenwich Railway divided the mill land into two uneven portions, with further railway works taking place in 1841 and 1850.[23]

Modern era

In 1935, Bevingtons moved most of their business to Dartford, keeping the smaller section of their divided site as a warehouse, and selling the larger portion to the Bermondsey Borough Council.[23] When Bevingtons sold the warehouse in early 1980s it was converted into a residential development,[23] and it has since been joined by new blocks of luxury flats, which coexist, with some friction, with the more bohemian houseboats moored offshore at Reed Wharf.[24][25]

The Neckinger, along with subterranean Thames tributaries, the Fleet and Tyburn, were mentioned in Neil Gaiman's 2013 short story Down to a Sunless Sea.[26][27]

See also

References

- ↑ "Geraldine Mary Harmsworth Park (including Imperial War Museum)". London Parks & Gardens Trust. Retrieved 2014-08-07.

- 1 2 Paul Talling (2011). London's Lost Rivers. Random House. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-84794-597-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Christopher Hibbert (5 August 2008). The London Encyclopaedia. Pan Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-74328-235-9.

- 1 2 Leigh Hatts (2 September 2011). The Thames Path: From London to Source. Cicerone Press Limited. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-84965-463-0.

- ↑ Henry Benjamin Wheatley; Peter Cunningham (24 February 2011). London Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions. Cambridge University Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-108-02807-3.

- 1 2 Rendle, William; Norman, Philip (1888). "XIII". The Inns of Old Southwark And Their Associations. London: Longman, Green & Co. p. 393. Retrieved 2014-08-11.

- ↑ Besant, Walter (1912). London South Of The Thames. London: Adam & Charles Black. pp. 67–68. Retrieved 2014-08-11.

- ↑ Charles Dickens (1861). All the Year Round. Charles Dickens. p. 470.

- ↑ Edward Wedlake Brayley (1829). Londiniana: Or, Reminiscences of the British Metropolis: Including Characteristic Sketches, Antiquarian, Topographical, Descriptive, and Literary. Hurst, Chance, and Company. pp. 52–54.

- ↑ David Hughson (1808). London; Being an Accurate History and Description of the British Metropolis and Its Neighbourhood: To Thirty Miles Extent, from an Actual Perambulation. W. Stratford. p. 60.

- ↑ A. D. Mills (11 March 2010). A Dictionary of London Place-Names. Oxford University Press. pp. 173–. ISBN 978-0-19-956678-5.

- ↑ Woodward, Horace (1922). The geology of the London district, being the area included in the four sheets of the special map of London. Lords Commissioners of His Majesty's Treasury. p. 78. Retrieved 2014-08-07.

- ↑ Walford, Edward (1873). Old and new London : a narrative of its history, its people, and its places. VI. London: Cassell, Petter and Galpin. pp. 250=251. Retrieved 2014-08-07.

- 1 2 Geoff Marshall (31 March 2013). London's Industrial Heritage. History Press Limited. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-7524-9239-1.

- ↑ BBC London, A Thames Tour of Rotherhithe

- ↑ John Wells’s phonetic blog, Redriff, 31 October 2007

- ↑ G. W. Phillips (of Bermondsey.) (1841). The history and antiquities of the parish of Bermondsey. J. Unwin. pp. 104–.

- 1 2 3 Walford, Edward (1873). Old and new London : a narrative of its history, its people, and its places. VI. London: Cassell, Petter and Galpin. pp. 125–126. Retrieved 2014-08-07.

- 1 2 Rendle, William (1878). Old Southwark And Its People. Southwark, London: W. Drewett. pp. 310–312. Retrieved 2014-08-11.

- 1 2 Kevin Flude; Paul Herbert (1 April 2001). The Citisights Guide to London: Ten Walks Through London's Past. iUniverse. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-595-18147-6.

- ↑ "Digging Jacob's Island". Current Archaeology. 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2014-08-07.

- ↑ Karen Mulhallen (2010). Blake in Our Time: Essays in Honour of G.E. Bentley Jr. University of Toronto Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-4426-4151-8.

- 1 2 3 Historic England. "Neckinger Mills (Grade II*) (1393907)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ↑ "The battle of the houseboats". infed.org. YMCA George Williams College. Retrieved 2014-08-07.

- ↑ Bar-Hillel, Mira (2004-09-17). "Star Trek captain wins houseboat battle". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- ↑ "Down to a Sunless Sea by Neil Gaiman". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media. 2013-03-22. Retrieved 2014-08-14.

- ↑ Stephen Jones (26 September 2013). Fearie Tales: Stories of the Grimm and Gruesome. Quercus Publishing. pp. 33–36. ISBN 978-1-78206-471-8.

External links

- Course of the River Neckinger on Google Maps.

- "Walking The Neckinger" from Changing London, the magazine of the London City Mission [PDF].

| Next confluence upstream | River Thames | Next confluence downstream |

| Walbrook (north) | River Neckinger | Regent's Canal (north) |

Coordinates: 51°30′02″N 0°04′24″W / 51.50056°N 0.07333°W