Central American river turtle

| Central American river turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Sauropsida |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Kinosternoidea |

| Family: | Dermatemydidae |

| Genus: | Dermatemys Gray, 1847[2] |

| Species: | D. mawii |

| Binomial name | |

| Dermatemys mawii Gray, 1847[2] | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

The Central American river turtle (Dermatemys mawii), also known locally as the hickatee or tortuga blanca (white turtle),[8] is the only living species in the family Dermatemydidae. Its closest relatives are only known from fossils with some 19 genera described from a worldwide distribution from the Jurassic and Cretaceous.[8] The species is currently found in the Atlantic drainages of Central America, specifically southern Mexico, Belize and Guatemala.[8] It is a relatively large-bodied species, with historical records of 60 cm (24 in) and weights of 22 kg (49 lb); however, more recent records have found few individuals over 14 kg (31 lb) in Mexico or 11 kg (24 lb) in Guatemala.[8]

Etymology

The specific name, mawii, is in honor of the collector of the type specimen, Lieutenant Mawe of the British Navy.[9]

Description

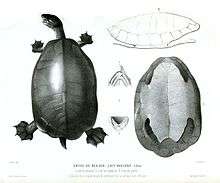

D. mawii has a low, flattened, smooth carapace with a median keel present in juveniles, it is usually a uniform brown, almost black, gray or olive in color.[8] The plastron is usually white to yellow, though may acquire substrate staining in some areas.[8] In juveniles, a distinctive keel is found down the center of the carapace, and the outer edges have serrations. These features are lost as the turtle ages. Its skin is predominantly the same color as the shell, with reddish or peach-colored markings around the neck and underside. Males can be differentiated from females by yellow markings on either side of their heads, and longer, thicker tails.

Behavior and Habitat

D. mawii is a nocturnal, completely aquatic turtle that lives in Atlantic-draining larger rivers and lakes in Central America, from southern Mexico to the Guatemalan-Honduran border.[8] The species is entirely aquatic and does not bask or leave the water, except to lay eggs.

Diet

D. mawii is entirely herbivorous; it eats figs and flowers opportunistically, but the majority of its diet are the leaves of terrestrial trees.[8]

Reproduction

The exact reproductive season for this species has been confused in the literature.[10] However, it is possible that a combination of a diapause and variable local reproductive cues is responsible for this. There appears to be a primary breeding season timed with the later part of the rainy season (September to December)[11] and a secondary one at the beginning of the dry season (January to February).[8] The species can lay up to 4 clutches per year with an average of 2–20 eggs per clutch; clutch sizes over 15, however, were not common.[8][11]

Conservation status

D. mawii is a heavily exploited turtle and is currently classified as Critically Endangered[1] and is listed as Endangered under the US Endangered Species Act. The Central American river turtle has been intensely harvested, primarily for its meat, but also for its eggs and shells. The turtle is now uncommon from much of its former range in southern Mexico and individual size is smaller.[8] Rarely found in captivity, the species has been overhunted because of its value in the food market.[12] Even the hatchlings and eggs are sold as food. The species' normally passive nature makes it relatively easy to catch. As such, it has been listed as a CITES Appendix II to prevent exportation, and local laws are in place to prevent them from being hunted.

Conservation efforts in Belize

On 7 December 2010, the first hickatee conservation forum[13] and workshop was held at the University of Belize, Belmopan campus presented by the Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA), in collaboration with the Belize Foundation for Research and Environmental Education (BFREE), the Environmental Research Institute at UB and the Belize Fisheries Department. The purpose of the workshop was to bring together members of the scientific community, government officials, NGOs and civil society to share information regarding the critically endangered Dermatemys mawii.

The Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA), an international conservation partnership, is committed to preventing turtle extinctions. Focusing on species ranked critically endangered, the TSA supports projects or programs around the world with an emphasis on Madagascar and Asia. An important aspect of the meeting was to share the results of a recent country-wide survey of hickatee; it was conducted in April–May, and was supported by TSA[14] in conjunction with local NGOs, and civil society under the authority of the Belize Fisheries Department. Results of the survey indicated the population is clearly headed towards extinction in Belize unless conservation measures are put in place. Local population extinctions have been documented, and current harvesting rates have been determined to be unsustainable. When compared to previous surveys, the most recent survey indicates the overall populations of hickatee continue to decline across the nation.

Captive turtle breeding program in Belize

A study, managed by the Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA) and conducted on Belize Foundation for Research and Environmental Education (BFREE) property in Belize, began in early 2011 and is a low-maintenance operation focused on generating Dermatemys food plants, while exploring husbandry details, such as egg laying and incubation. Located in southern Belize along the Bladen River, BFREE encompasses 1,200 acres (4.9 km2) of forest and is situated among four protected areas (Bladen Nature Reserve, Cockscomb Basin Jaguar Reserve, Deep River Forest Reserve and Maya Mountain Forest Reserve), which enhances the possibility of a successful breeding program.

The goal of the program is to generate hatchlings and release them to repopulate already depleted wild populations and, ultimately, relieve pressures of local populations. The program has the potential to be expanded once it is determined whether the species can be reliably reproduced in good numbers in captivity.

References

- 1 2 Vogt, R.C.; Gonzalez-Porter, G.P. & Van Dijk, P.P. (2006). "Dermatemys mawii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 Gray, John Edward. 1847. Description of a new genus of Emydae. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1847(15):55–56.

- ↑ Turtle Taxonomy Working Group [van Dijk , P.P., Iverson, J.B., Shaffer, H.B., Bour, R., and Rhodin, A.G.J.]. 2012. Turtles of the world, 2012 update: annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution, and conservation status. Chelonian Research Monographs No. 5, pp. 000.243–000.328, doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v5.2012, .

- ↑ Duméril, André Marie Constant & Bibron, Gabriel. 1851. [Emys areolata, Emys berardii, Cinosternon leucostomum, Cinosternon cruentatum]. In: Duméril, A.M.C. & Duméril, A.H.A. Catalogue Methodique de la Collection des Reptiles (Museum d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris). Paris: Gide and Baudry, 224 pp.

- ↑ Cope, Edward D. 1868. An examination of the Reptilia and Batrachia obtained by the Orton expedition to Equador [sic] and the upper Amazon, with notes on other species. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 20:96–140.

- ↑ Gray, John Edward. 1870b. Supplement to the Catalogue of Shield Reptiles in the Collection of the British Museum. Part I. Testudinata (Tortoises). London: British Museum, 120 pp.

- ↑ Werner, Franz. 1901. Neue Reptilien des Königsberger zoologischen Museums. Zoologischer Anzeiger 24:297–301.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Vogt, R.C., Polisar, J.R., Moll, D., & Gonzalez-Porter, G. 2011. Dermatemys mawii Gray 1847 – Central American River Turtle, Tortuga Blanca, Hickatee. In: Rhodin, A.G.J., Pritchard, P.C.H., van Dijk, P.P., Samure, R.A., Buhlmann, K.A., Iverson, J.B., & Mittermeier, R.A. (Eds.) Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation Project of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. Chelonian Research Monographs No. 5, pp. 058.1–058.12, doi:10.3854/crm.5.058.mawii.v1.2011, .

- ↑ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael. 2011. The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Dermatemys mawii, p. 171).

- ↑ Lee, J.C. The Amphibians and Reptiles of the Yucatán Peninsula. Comstock Publishing Associates, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York. pp 500.

- 1 2 Polisar, J. 1996. Reproductive biology of a flood-season nesting freshwater turtle of the northern neotropics: Dermatemys mawii in Belize. Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 2(1):13–15

- ↑ Polisar, J. (1997) Effects of exploitation on Dermatemys mawii populations in northern Belize and conservation strategies for rural riverside villages. pp. 441–443

- ↑ Rainwater, Thomas. "Finishing up the Hicatee Workshops in Belize". Turtle Survival Alliance blog. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ↑ Rainwater, T., Pop, T., Cal, O., Platt, S., & Hudson, R. 2010. Catalyzing Conservation in Belize for Central America's Imperiled River Turtle. Turtle Survival Alliance Magazine, August 2010, pp. 79–82.

| Wikispecies has information related to: Dermatemys mawii |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dermatemys mawii. |