Robert Emmet

| Robert Emmet | |

|---|---|

A watercolor miniature made of Emmet during his trial. | |

| Born |

4 March 1778 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died |

20 September 1803 (aged 25) Dublin |

| Allegiance | United Irishmen |

| Years of service | 1793–1803 |

| Rank | Commander |

| Battles/wars |

1798 Rebellion Irish Rebellion of 1803 |

| Relations | Thomas Addis Emmet |

Robert Emmet (4 March 1778 – 20 September 1803) was an Irish nationalist and Republican, orator and rebel leader. After leading an abortive rebellion against British rule in 1803 he was captured then tried and executed for high treason against the British king.[1]

He came from a wealthy Anglo-Irish Protestant family who sympathised with Irish Catholics and their lack of fair representation in Parliament. The Emmet family also sympathised with the rebel colonists in the American Revolution. While Emmet's efforts to rebel against British rule failed, his actions and speech after his conviction inspired his compatriots.[2]

Early life

He was born at 109 St. Stephen's Green,[3][4] in Dublin on 4 March 1778. He was the youngest son of Dr Robert Emmet (1729–1802), a court physician, and his wife, Elizabeth Mason (1739–1803). The Emmets were financially comfortable, with a house at St Stephen's Green and a country residence near Milltown. One of his elder brothers was the nationalist Thomas Addis Emmet, a close friend of Theobald Wolfe Tone, who was a frequent visitor to the house when Robert was a child.

Emmet attended Oswald's school, in Dopping's-court, off Golden-lane.[5] Emmet entered Trinity College, Dublin in October 1793, at the age of fifteen. In December 1797 he joined the College Historical Society, a debating society. While he was at college, his brother Thomas and some of his friends became involved in political activism. Robert became secretary of a secret United Irish Committee in college, and was expelled in April 1798 as a result. That same year he fled to France to avoid the many British arrests of nationalists that were taking place in Ireland. While in France, Emmet garnered the support of Napoleon, who had promised to lend support when the upcoming revolution started.[6]

After the 1798 rising, Emmet was involved in reorganising the defeated United Irish Society. In April 1799 a warrant was issued for his arrest. He escaped and soon after travelled to the continent in the hope of securing French military aid. His efforts were unsuccessful, as Napoleon was concentrating his efforts on invading England. Emmet returned to Ireland in October 1802. In March the following year, he began preparations for another uprising.

1803 rebellion

After his return to Ireland, Emmet began to prepare a new rebellion, with fellow Anglo-Irish revolutionaries Thomas Russell and James Hope. He began to manufacture weapons and explosives at a number of premises in Dublin and developed a folding pike fitted with a hinge that allowed it to be concealed under a cloak. Unlike in 1798, the revolutionaries concealed their preparations, but a premature explosion at one of Emmet's arms depots killed a man. Emmet was forced to advance the date of the rising before the authorities' suspicions were aroused.

Emmet was unable to secure the help of Michael Dwyer's Wicklow rebels.[7] Many rebels from Kildare turned back due to the scarcity of firearms they had been promised, but the rising went ahead in Dublin on the evening of 23 July 1803. About 10,000 copies were printed of a proclamation in the name of the "Provisional Government", which influenced the 1916 Proclamation; most were destroyed by the authorities.[8]

Emmet wore a uniform of a green coat with white facings, white breeches, top-boots, and a cocked hat with feathers.[5] Failing to seize Dublin Castle, which was lightly defended, the rising amounted to a large-scale disturbance in the Thomas Street area. Emmet saw a dragoon being pulled from his horse and piked to death, the sight of which prompted him to call off the rising to avoid further bloodshed. But, he had lost all control of his followers. In one incident, the Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, Lord Kilwarden, was dragged from his carriage and stabbed by pikes. Found still alive, he was taken to a watch-house where he died shortly thereafter. He had been reviled as chief prosecutor of William Orr in 1797, but he was also the judge who granted habeas corpus to Wolfe Tone in 1798. Kilwarden's nephew, the Rev. Mr. Wolfe, was also killed. Sporadic clashes continued into the night until finally quelled by British military forces.

Capture and trial

Emmet fled into hiding, moving from Rathfarnam to Harold's Cross so that he could be near his sweetheart, Sarah Curran. He likely could have escaped to France, had he not insisted upon returning with Anne Devlin in order to take leave of Sarah Curran, to whom he was engaged. She was daughter of John Philpot Curran.[5] Emmet was captured on 25 August and taken to the Castle, then removed to Kilmainham. Vigorous but ineffectual efforts were made to procure his escape.

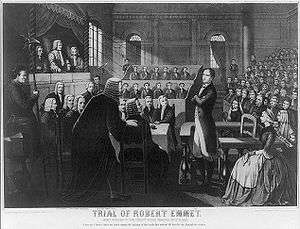

He was tried for treason on 19 September; the Crown repaired the weaknesses in its case by secretly buying the assistance of Emmet's defence attorney, Leonard McNally, for £200 and a pension.[9] But McNally's assistant Peter Burrowes could not be bought and he pleaded the case as best he could.[7] On 19 September, Emmet was found guilty of high treason.

Before sentencing Emmet delivered a speech, the Speech from the Dock., It is especially remembered for its closing sentences and secured his posthumous fame among executed Irish republicans. It was printed in 1835 in Manchester for the bookseller TP Carlile.[10]

Let no man write my epitaph; for as no man who knows my motives dare now vindicate them, let not prejudice or ignorance, asperse them. Let them and me rest in obscurity and peace, and my tomb remain uninscribed, and my memory in oblivion, until other times and other men can do justice to my character. When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then and not till then, let my epitaph be written. I have done.[11]

An earlier and perhaps more accurate version of the speech was published in 1818, in a biography on Sarah Curran's father John, emphasising that Emmet's epitaph would be written on the vindication of his character, and not specifically when Ireland took its place as a nation. It closed:[12]

I am here ready to die. I am not allowed to vindicate my character; no man shall dare to vindicate my character; and when I am prevented from vindicating myself, let no man dare to calumniate me. Let my character and my motives repose in obscurity and peace, till other times and other men can do them justice. Then shall my character be vindicated; then may my epitaph be written.

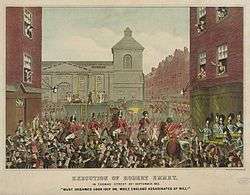

Chief Justice Lord Norbury sentenced Emmet to be hanged, drawn and quartered, as was customary for conviction of treason. The following day, 20 September, Emmet was executed in Thomas Street near St. Catherine's. He was hanged and beheaded once dead.[1] As family members and friends of Robert had also been arrested, including some who had nothing to do with the rebellion, no one came forward to claim his remains out of fear of arrest.

Robert Emmet is described as slight in person; his features were regular, his forehead high, his eyes bright and full of expression, his nose sharp, thin, and straight, the lower part of his face slightly pock-marked, his complexion sallow.[5]

Burial

Emmet's remains were first delivered to Newgate Prison and then back to Kilmainham Gaol, where the jailer was under instructions that if no one claimed them they were to be buried in a nearby hospital's burial grounds called 'Bully's Acre' in Kilmainham. A later search there found no remains; it appears that Emmet's remains were secretly removed from Bully's Acre and reinterred in St Michan's, a Dublin church with strong United Irish associations, though it was never confirmed.[13]

Speculation has continued regarding the whereabouts of Emmet's remains. It was suspected that they were buried secretly in the vault of a Dublin Anglican church. When the vault was inspected in the 1950s a headless corpse was found, suspected of being Emmet's, but could not be identified. Widely accepted is the theory that Emmet's remains were transferred to St Peter's Church in Aungier St. under cover of the burial of Robert's sister, Mary Anne Holmes, in 1804.[1] In the 1980s the church was deconsecrated and all the coffins were removed from the vaults. The church has since been demolished.

Legacy

Emmet became a heroic figure in Irish history. His speech from the dock is widely quoted and remembered, especially among Irish nationalists. As he and his family also supported the American Revolutionary War, he is remembered there as well.[14][15] Emmet's housekeeper, Anne Devlin, is also remembered in Irish history for enduring torture without providing information to the authorities.[1]

Robert Emmet's older brother, Thomas Addis Emmet emigrated to the United States shortly after Robert's execution. He eventually served as the New York State Attorney General. His descendants include the prominent American portrait painters Lydia Field Emmet, Rosina Sherwood Emmet, and Jane Emmet de Glehn, who were Robert Emmet's great-grand-nieces. Another descendant is American playwright Robert Emmet Sherwood.

Representation in popular culture

Robert Emmet wrote a letter from his cell in Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin on 8 September 1803. He addressed it to "Miss Sarah Curran, the Priory, Rathfarnham" and handed it to a prison warden, George Dunn, whom he trusted to deliver it. Dunn betrayed him and gave the letter to the government authorities. Due to Emmet's attempt to hide near Curran, which cost him his life, and his parting letter to her, Emmet became known as a legendary romantic character, appealing to the Victorian Era's appetite for Romanticism.

His story was the subject of stage melodramas during the 19th century, most notably Dion Boucicault's inaccurate 1884 play Robert Emmet. He mistakenly portrayed Emmet and Curran as Roman Catholics (they were both Protestants), her father John Philpot Curran being portrayed as a Unionist, and Emmet being killed onstage by firing squad.

Robert's friend from Trinity College, Thomas Moore, championed his cause by writing popular ballads about him and Sarah Curran, such as

- Oh breathe not his name! let it sleep in the shade,

- Where cold and unhonoured his relics are laid!

The poem "On Robert Emmet's Grave" by Percy Bysshe Shelley states that Emmet's grave will "remain unpolluted by fame", as its location is unknown:

- No trump tells thy virtues—the grave where they rest

- With thy dust shall remain unpolluted by fame,

- Till thy foes, by the world and by fortune caressed,

- Shall pass like a mist from the light of thy name.

[16]

Washington Irving, devoted "The Broken Heart" in his The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. to the romance between Emmet and Sarah Curran, citing it as an example of how a broken heart can be fatal.

The American film by Irish-Canadian Sidney Olcott entitled All for Old Ireland (1915), is also known as Bold Emmett, Ireland's Martyr or Robert Emmet, Ireland's Martyr.[17]

Honors

Places named after Emmet in the United States include Emmetsburg, Iowa;[14] Emmet, Nebraska;[18] Emmet County, Iowa; Emmett, Michigan and Emmet County, Michigan.[19] The Robert Emmet Elementary School in Chicago, Illinois was named for him. Robert Emmets GAA club is named after him.

Statues were erected in his honor:

- A bronze statue of him by Jerome Connor stands in Washington, DC on Embassy Row (Massachusetts Avenue NW and S Street NW). A public commemoration of Emmet's execution and legacy is held annually on the fourth Sunday in September by the Irish American Unity Conference.

- A copy of this statue was installed in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park.

- Bronze statue of Robert Emmet, 1916, by Jerome Connor, from the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. It is installed in Washington, DC's Embassy Row.[20]

Statue of Robert Emmet in St. Stephens Green, Dublin

Statue of Robert Emmet in St. Stephens Green, Dublin

- A statue of Emmet is in the courthouse square in Emmetsburg, Iowa.

See also

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Robert Emmet |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Emmet. |

References

- 1 2 3 4 Murphy, Sean. "The Grave of Robert Emmet", Irish Historical Mysteries, Dublin, Ireland; 2010

- ↑ "Robert Emmet: Beliefs in the Arena by:Joshua Allen MacVey". The Robert Emmet Society. 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ↑ Kilfeather, Siobhán Marie (2005). Dublin: a cultural history. Oxford University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-19-518201-9. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- ↑ Geoghegan, Patrick M (2002). Robert Emmet: a life. Gill & Macmillan. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7171-3387-1. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Webb, Alfred. A Compendium of Irish Biography, M.H. Gill & Son, Dublin, 1878

- ↑ "The Emmet Rebellion". Triskelle. 2010. Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- 1 2 "Robert Emmet". Ricorso. 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ↑ Geoghegan, Patrick M. (Autumn 2003). "[Which] Speech from the Dock?". History Ireland. 11 (3).

- ↑ "The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2008". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ↑ 1835 text online; accessed April 8, 2014

- ↑ Speeches from the Dock, T.D., A.M., and D.B. Sullivan, Re Edited by Seán Ua Cellaigh, M.H. Gill & Son, Dublin, 1953, pg.60

- ↑ Phillips, C. Recollections of Curran (1818 Milliken, Dublin) pp.256–259.

- ↑ Sean Murphy, Bully's Acre and Royal Hospital Kilmainham Graveyards: History and Inscriptions, Dublin 1989

- 1 2 "A Small Town Struggles to Preserve Its Irish Heritage". Irish America Magazine Sept/Oct. 1993.

- ↑ Ruán O’Donnell (July 2003). "Robert Emmet: enigmatic revolutionary". Irish Democrat.

- ↑ Esdaile manuscript book by Dowden, "Life of Shelley", 1887; dated 1812

- ↑ The Story of Irish Film, by Arthur Flynn, Currach Press, Dublin, 2005 ISBN 1-85607-914-7.

- ↑ Campbell, Dorine. "Emmet". Nebraska...Our Towns Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 119.

- ↑ ""Robert Emmet" by Jerome Connor". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

Bibliography

- Elliott, Marianne. Robert Emmet: The Making of a Legend

- Geoghegan, Patrick. Robert Emmet: A Life (Gill and Macmillan) ISBN 0-7171-3387-7

- Gough, Hugh & David Dickson, editors. Ireland and the French Revolution

- McMahon, Sean. Robert Emmet

- O Bradaigh, Sean. Bold Robert Emmet 1778–1803

- O'Donnell, Ruan. Robert Emmet and the Rebellion of 1798

- _____. Robert Emmet and the Rising of 1803

- _____. Remember Emmet: Images of the Life and legacy of Robert Emmet

- Smyth, Jim. The Men of No Property: Irish Radicals and Popular Politics in the Late Eighteenth Century

- Stewart, A.T.Q. A Deeper Silence: The Hidden Origins of the United Irish Movement

External links

- Robert Emmet

- Robert Emmet index of articles in History Ireland

- History of Dublin Castle, Chapter 13. Emmet's execution

- DNA tests to tell if skull is Emmet's

- Emmet's 'Proclamation of Independence'

- Robert Emmet's Speech (Unabridged) From the Dock

- Bronze sculpture of Robert Emmet (1916), by Jerome Stanley Connor, in Emmet Park, Washington, DC (photos)

- Éamon De Valera unveils statue of Robert Emmet in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, 20 July 1919

- Smithsonian American Art Museum's Art Inventories Catalog record of the Robert Emmet Statue in Washington, D.C.

- Robert Emmet Museum