Rodolphe Töpffer

| Rodolphe Töpffer | |

|---|---|

Self portrait of Rodolphe Töpffer (1840) | |

| Born |

31 January 1799 Geneva, Léman, Helvetic Republic |

| Died |

8 June 1846 (aged 47) Geneva, Switzerland |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Occupation |

|

Rodolphe Töpffer (31 January 1799 – 8 June 1846) was a Swiss teacher, author, painter, cartoonist, and caricaturist. He is best known for his illustrated books (littérature en estampes, "graphic literature"),[1] which can be seen as the earliest European comics.

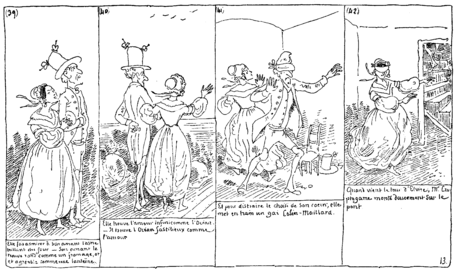

Paris-educated, Töpffer worked as a schoolteacher and ran a boarding school, where he entertained students with his caricatures. In 1837, he published Histoire de M. Vieux Bois (published in the United States in 1842 as The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck). Each page of the book had one to six captioned cartoon panels, much like modern comics. Töpffer published several more of these books, and wrote theoretical essays on the form.

Biography

Töpffer was born on 31 January 1799 in Geneva, Switzerland. His father, painter and occasional caricaturist Wolfgang-Adam Töpffer, had come from Franconia.[2] Rodolphe was educated in Paris from 1819 to 1820, then returned to Geneva and became a school teacher. By 1823 he established his own boarding school for boys. In 1832 he was appointed Professor of Literature at the University of Geneva.[3]

Relatively successful in his profession, Rodolphe gained fame from activities he pursued in his spare time. He painted local landscapes in a style considered influenced by contemporary Romanticism. He wrote short stories and entertained his students by drawing caricatures. He collected these caricatures in books; the first of them, Histoire de M. Vieux Bois ("The Story of Mr. Wooden Head"), was completed by 1827 but not published until 1837. It was 30 pages, each containing one to six captioned panels. It was translated and republished in the United States in 1842 as The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck. The stories were reproduced by autography, a variation of lithography that allowed him to draw on specially prepared paper with a pen. The process allowed for a loose line, and was quicker and freer than the more common engraving process.

Publications

The comedic story was not originally intended for publication but Rodolphe continued to create others in his spare time to entertain his acquaintances. Notable among them was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe who in 1831 persuaded Rodolphe to publish his stories.[4] Seven of them were eventually published in newspaper form across Europe but Goethe would not live to see them.

- Histoire de M. Jabot – created 1831, first published 1833. It features the adventures of a middle class dandy who attempts to enter contemporary Upper class.

- Monsieur Crépin – first published in 1837. It features the adventures of a father who employs a series of tutors for his children and falls prey to their eccentricities.

- Histoire de M. Vieux Bois – created 1827, first published 1837. The above-mentioned story.

- Monsieur Pencil – created 1831, first published 1840. An escalating series of events beginning with an artist losing his sketch to the blowing wind and almost resulting in a global war.

- Histoire d'Albert – first published in 1845. The adventures of an inexperienced young man in search of a career. After many attempts he ends up as a journalist in support of radical ideas.

- Histoire de Monsieur Cryptogame – first published in 1845. The story of a lepidopterist who goes to great lengths to replace his current lover with a more suitable one.

- Le Docteur Festus- created 1831, first published 1846. A scientist wanders the world, offering his assistance. He is blissfully unaware that disaster marks his path.

All seven are considered satirical views of 19th century society and proved popular at the time. In 1842 Rodolphe published Essais d'autographie. On 14 September 1842 the Histoire de M. Vieux Bois was first introduced to a United States audience as The Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck. It was published in comic book form as a supplement to that day's edition of Brother Jonathan, a New York, New York newspaper published by author John Neal (25 August 1793 – 20 June 1876). It has come to be considered the first American comic book and, according to several Robert Beerbohm articles published in Comic Art and the Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide, the inspiration for an entire U.S. genre of nineteenth-century graphic novel.

The University Press of Mississippi published an English translation of his full-length stories as well as previously unpublished works in 2007.

Rodolphe is considered alternatively the father or at least an important precursor to the modern art form of comics. He is also considered to be an influence to younger comic artists such as Wilhelm Busch (15 April 1832 – 9 January 1908), creator of Max and Moritz.

Child art

Töpffer wrote two chapters on child art and child creativity in his book Reflections et menus propos d'un peintre genevois (1848), which was published after his death. He wrote that children often displayed greater creativity than trained artists, whose creativity was often overshadowed by their technical skill.[5]

Notes

- ↑ M. Keith Booker (ed.), Comics through Time: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2014, p. 395.

- ↑ Kunzle 2007, p. xiii.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ Thierry Groensteen and Benoît Peeters, Töpffer, l'invention de la bande dessinée, Paris: Hermann, "Savoir : sur l'art" Collection, 1994, p. 83.

- ↑ Wilson 2004, p. 305.

References

- Kunzle, David (2007). Father of the Comic Strip: Rodolphe Töpffer. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-947-7.

- Wilson, Brent (2004). "14: Child Art After Modernism: Visual Culture and New Narratives". In Eisner, Elliot W.; Day, Michael D. Handbook of Research and Policy in Art Education. Routledge. pp. 299–328. ISBN 978-0-8058-4972-1.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Töpffer, Rodolphe". Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Töpffer, Rodolphe". Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rodolphe Töpffer. |

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about Rodolphe Töpffer. |

- An online version of his first illustrated story, Les Amours de Monsieur Vieux-Bois, in manuscript form

- Pictures and texts of Voyages en zigzag, ou excursions d'un pensionnat en vacances dans les cantons suisses et sur le revers italien des Alpes by Rodolphe Töpffer can be found in the database VIATIMAGES.

- The story Histoire d'Albert as PDF-file

- Published version of the above story

- A critical biography of Töpffer

- The complete comics of Töpffer and first English translation