Roof tiles

Roof tiles are designed mainly to keep out rain, and are traditionally made from locally available materials such as terracotta or slate. Modern materials such as concrete and plastic are also used and some clay tiles have a waterproof glaze.

Roof tiles are 'hung' from the framework of a roof by fixing them with nails. The tiles are usually hung in parallel rows, with each row overlapping the row below it to exclude rainwater and to cover the nails that hold the row below. There are also roof tiles for special positions, particularly where the planes of the several pitches meet. They include ridge, hip and valley tiles. These can either be bedded and pointed in cement mortar or mechanically fixed.

Similarly to roof tiling, tiling has been used to provide a protective weather envelope to the sides of timber frame buildings. These are hung on laths nailed to wall timbers, with tiles specially molded to cover corners and jambs. Often these tiles are shaped at the exposed end to give a decorative effect. Another form of this is the so-called mathematical tile, which was hung on laths, nailed and then grouted. This form of tiling gives an imitation of brickwork and was developed to give the appearance of brick, but avoided the brick taxes of the 18th century.[1]

Slate roof tiles were traditional in some areas near sources of supply, and gave thin and light tiles when the slate was split into its natural layers. It is no longer a cheap material, however, and is now less common.

Shapes (profiles)

A large number of shapes (or "profiles") of roof tiles have evolved. These include:

- Flat tiles – the simplest type, which are laid in regular overlapping rows. An example of this is the clay-made "beaver-tail" tile (German Biberschwanz), common in Southern Germany. Flat roof tiles are usually made of clay but also may be made of stone, wood, plastic, concrete, or solar cells.

- Imbrex and tegula – an ancient Roman pattern of curved and flat tiles that make rain channels on a roof.

- Roman tiles – flat in the middle, with a concave curve at one end at a convex curve at the other, to allow interlocking.

- Pantiles – with an S-shaped profile, allowing adjacent tiles to interlock. These result in a ridged pattern resembling a ploughed field. An example of this is the "double Roman" tile, dating from the late 19th century in England and US.

- Mission or barrel tiles – semi-cylindrical tiles laid in alternating columns of convex and concave tiles. Originally they were made by forming clay around a curved surface, often a log or the maker's thigh. Today barrel tiles are mass-produced from clay, metal, concrete or plastic.

- Interlocking roof tiles – similar to pantiles with side and top locking to improve protection from water and wind.

- Antefixes – vertical blocks which terminate the covering tiles of a tiled roof.

History

Fired roof tiles are found as early as the 3rd millennium BC in the Early Helladic House of the tiles in Lerna, Greece.[2][3] Debris found at the site contained thousands of terracotta tiles having fallen from the roof.[4] In the Mycenaean period, roofs tiles are documented for Gla and Midea.[5]

The earliest finds of roof tiles in archaic Greece are documented from a very restricted area around Corinth, where fired tiles began to replace thatched roofs at two temples of Apollo and Poseidon between 700 and 650 BC.[6] Spreading rapidly, roof tiles were within fifty years in evidence for a large number of sites around the Eastern Mediterranean, including Mainland Greece, Western Asia Minor, and Southern and Central Italy.[7] Early roof tiles showed an S-shape, with the pan and cover tile forming one piece. They were rather bulky affairs, weighing around 30 kg (66 lb) apiece.[8] Being more expensive and labour-intensive to produce than thatch, their introduction has been explained by their greatly enhanced fire resistance, which gave desired protection to the costly temples.[9]

The spread of the roof tile technique has to be viewed in connection with the simultaneous rise of monumental architecture in ancient Greece. Only the newly appearing stone walls, which were replacing the earlier mudbrick and wood walls, were strong enough to support the weight of a tiled roof.[10] As a side-effect, it has been assumed that the new stone and tile construction also ushered in the end of 'Chinese roof' (Knickdach) construction in Greek architecture, as they made the need for an extended roof as rain protection for the mudbrick walls obsolete.[11]

Production of dutch roof tiles started in the 14th century when city rulers required the use of fireproof materials. At the time, most houses were made of wood and had thatch roofing, which would often cause fires to quickly spread. To satisfy demand, many small roof tile makers began to produce roof tiles by hand. Many of these small factories were built near rivers where there was a ready source of clay and cheap transport.

Tilehanging

Tilehanging or vertical tiling is the construction of a building with roof tiles hung vertically on the sides of the building.[12] It is a popular style used in vernacular and neo-vernacular architecture in Britain.[13]

Solar Roof Tiles

Dow Chemical Company began producing solar roof tiles in 2005, and several other manufacturers followed suit. They are similar in design to conventional roof tiles but with a photovoltaic cell within in order to generate renewable electricity. A collaboration between the companies SolarCity and Tesla Motors produced a hydrographically printed tile, that look like regular tiles from ground level but are transparent to sunlight when viewed straight on.[14]

See also

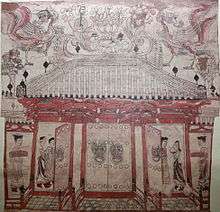

- Chinese glazed roof tile

- Roof tile−related topics

References

- ↑ RW Brunskill, Illustrated Handbook of Vernacular Architecture (1970:58-61)

- ↑ Joseph W. Shaw, The Early Helladic II Corridor House: Development and Form, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 91, No. 1. (Jan. 1987), pp. 59–79 (59)

- ↑ John C. Overbeck, “Greek Towns of the Early Bronze Age”, The Classical Journal, Vol. 65, No. 1. (Oct. 1969), pp. 1–7 (5)

- ↑ J. L. Caskey, "Lerna in the Early Bronze Age", American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 72, No. 4. (Oct. 1968), pp. 313-316 (314)

- ↑ Ione Mylonas Shear, "Excavations on the Acropolis of Midea: Results of the Greek-Swedish Excavations under the Direction of Katie Demakopoulou and Paul åström", American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 104, No. 1. (Jan. 2000), pp. 133–134

- ↑ Örjan Wikander, p. 285

- ↑ Örjan Wikander, p. 286

- ↑ William Rostoker; Elizabeth Gebhard, p. 212

- ↑ Örjan Wikander, p. 289

- ↑ Marilyn Y. Goldberg, p. 309

- ↑ Marilyn Y. Goldberg, p. 305

- ↑ Stephen Emmitt; Christopher A. Gorse (5 February 2013). Barry's Introduction to Construction of Buildings. John Wiley & Sons. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-118-65858-1.

- ↑ Paul Hymers (2004). Home Renovations. New Holland Publishers. pp. 123–4. ISBN 978-1-84330-696-2.

- ↑ Becker, Rachel. "Check out Tesla's four different glass solar roofs". The Verge.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roof tiles. |