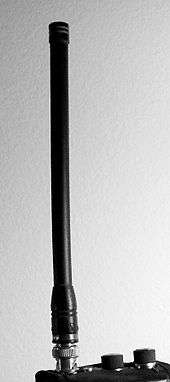

Rubber ducky antenna

The rubber ducky antenna (or rubber duck aerial) is an electrically short monopole antenna that functions somewhat like a base-loaded whip antenna. It consists of a springy wire in the shape of a narrow helix, sealed in a rubber or plastic jacket to protect the antenna.[1]

Electrically short antennas like the rubber ducky are used in portable handheld radio equipment at VHF and UHF frequencies in place of a quarter wavelength whip antenna, which is inconveniently long and cumbersome at these frequencies. Many years after its invention in 1958, the rubber ducky antenna became the antenna of choice for many portable radio devices, including walkie-talkies and other portable transceivers, scanners and other devices where safety and robustness take precedence over antenna capabilities.

Origin of the name

Two rumors link the naming of the antenna with the Kennedy family.[1] In the early 1960s the rubber ducky became the antenna of choice for personal walkie-talkie transceivers used by police and security services, including the U.S. Secret Service, which guards the President of the United States. According to one rumor, the young Caroline Kennedy, daughter of President John F. Kennedy, named the flexible device when she pointed at one on an agent's transceiver and said, "rubber ducky". On the other hand Dr. Thomas A. Clark, a senior scientist with NASA, claims to have named it after listening to one of Vaughn Meader's comedies about the Kennedy family.

An alternative name is based on the short stub format: the "stubby antenna".[2][3][4]

Description

Before the rubber ducky, antennas on portable radios usually consisted of quarter-wave whip antennas, rods whose length was one-quarter of the wavelength of the radio waves used.[1] In the VHF range where they were used, these antennas were 2 or 3 feet long, making them cumbersome. They were often made of telescoping tubes that could be retracted when not in use. To make the antenna more compact, electrically short antennas, shorter than one-quarter wavelength, began to be used. Electrically short antennas have considerable capacitive reactance, so to make them resonant at the operating frequency an inductor (loading coil) is added in series with the antenna. Antennas which have these inductors built into their bases are called base-loaded whips.

The rubber ducky is an electrically short quarter-wave antenna in which the inductor, instead of being in the base, is built into the antenna itself. The antenna is made of a narrow helix of wire like a spring, which functions as the needed inductor. The springy wire is flexible, making it less prone to damage than a stiff antenna. The spring antenna is further enclosed in a plastic or rubber-like covering to prevent it from catching on things. The technical name for this type of antenna is a normal-mode helix.[5] Rubber ducky antennas are typically 4% to 15% of a wavelength long;[5] that is, 16% to 60% of the length of a standard quarter-wave whip.

Effective aperture

Because the length of this antenna is significantly smaller than a wavelength the effective aperture is approximately:[6]

Although like other electrically short antennas the rubber ducky has poorer performance (less gain) than a quarter-wave whip, it has somewhat better performance than an equal length base loaded antenna. This is because the inductance is distributed throughout the antenna and so allows somewhat greater current in the antenna.

Performance

Rubber ducky antennas have lower gain than a full size quarter-wavelength antenna, reducing the range of the radio. They are typically used in short-range two way radios where maximum range is not a requirement. Their design is a compromise between antenna gain and small size. They are difficult to characterize electrically because the current distribution along the element is not sinusoidal as is the case with a thin linear antenna.

In common with other inductively loaded short monopoles, the rubber ducky has a high Q factor and thus a narrow bandwidth. This means that as the frequency departs from the antenna's designed center frequency, its SWR increases and thus its efficiency falls off quickly. This type of antenna is often used over a wide frequency range, e.g. 100-500 MHz, and over this range its performance is poor, but in many mobile radio applications there is sufficient excess signal strength to overcome any deficiencies in the antenna.

Design rules

- If the coils of the spring are wide (a large diameter), relative to the length of the array, the resulting antenna will have narrow bandwidth.

- Conversely, if the coils of the spring are narrow, relative to the length of the array, the resulting antenna will have its largest possible bandwidth.

- If the antenna is resonant, and the spring has a large diameter, the impedance will be well below 50 ohms, tending towards zero ohms with large inductors as the structure starts to resemble a series-tuned circuit with little radiation resistance.

- If the antenna is resonant, and the spring has a small diameter, the impedance will increase towards 70 ohms.

From these rules, one can surmise that it is possible to design a rubber ducky antenna that has about 50 ohms impedance at its feed-point, but a compromise of bandwidth may be necessary. Modern rubber ducky antennas such as those used on cell phones are tapered in such a way that few performance compromises are necessary.

Variations

Some rubber ducky antennas are designed quite differently than the original design. One type uses a spring only for support. The spring is electrically shorted out. The antenna is therefore electrically a linear element antenna. Some other rubber ducky antennas use a spring of non-conducting material for support and comprise a collinear array antenna. Such antennas are still called rubber ducky antennas even though they function quite differently (and often better) than the original spring antenna.

See also

- isotropic antenna

- omnidirectional antenna

- whip antenna

- driven element

- balun

- amateur radio

- shortwave listening

References

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Richard B. (2006). "Rubbber Ducky Antenna". Abominable Firebug. Richard Johnson's personal website. Retrieved 2011-04-06. External link in

|publisher=(help). A note at the bottom of the page says this page is not copyrighted, and text from this page has been quoted verbatim in this article - ↑ "Buy the coolest short stubby antenna for your car". Stubby Antenna. Retrieved 2014-06-24.

- ↑ "PMAE4002 - Motorola Solutions USA". Motorola.com. Retrieved 2014-06-24.

- ↑ https://www.google.com.au/search?q=stubby+antenna&hl=en&safe=off&rls=com.microsoft:en-au&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=LWpFUffFA5CaiAe9roCoBg&ved=0CJEBELAE&biw=1280&bih=842&sei=TmpFUaubIeSuiQfKhoHYCA

- 1 2 Fujimoto, Kyōhei (2001). Mobile antenna systems handbook, 2nd Ed. Artech House. p. 419. ISBN 1-58053-007-9.

- ↑ Kraus, John D. (1950). Antennas. McGraw-Hill. Chapter 3, The antenna as an aperture, pp 30.