National Library of Russia

| |

The 18th-century building of the library faces Nevsky Prospekt | |

| Country | Russia |

|---|---|

| Type | National library |

| Established | 1795 |

| Reference to legal mandate | Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation authorizing the Statute of the Federal State Institution "The National Library of Russia" (March 23, 2001) |

| Location | St Petersburg |

| Coordinates | 59°56′01″N 030°20′08″E / 59.93361°N 30.33556°ECoordinates: 59°56′01″N 030°20′08″E / 59.93361°N 30.33556°E |

| Collection | |

| Items collected | Books, journals, newspapers, magazines, official publications, sheet music, sound and music recordings, databases, maps, postage stamps, prints, drawings, manuscripts and media. |

| Size | 36,475,000 items (15,000,000 books) |

| Criteria for collection | Legal deposit of materials published in Russia; "Rossika": materials about Russia or materials published by the people of Russia residing abroad; selected foreign scholarly publications and other materials. |

| Legal deposit | Yes (Legal Deposit Law[1]) |

| Access and use | |

| Access requirements | Reading rooms – free. Russian residents must be 14 or older. Foreign visitors are limited by the period of their visa. |

| Circulation | 8,880,000 (2007) |

| Population served | 1,150,000 (2007) |

| Other information | |

| Budget | 569,200,000 RUB ($23,400,000) |

| Staff | 1,850 |

| Website |

www |

The National Library of Russia in St Petersburg (known as the Imperial Public Library from 1795 to 1917; Russian Public Library from 1917 to 1925; State Public Library from 1925 to 1992 (since 1932 named after M.Saltykov-Shchedrin); NLR), is not only the oldest public library in the nation, but also the first national library in the country. The NLR is currently ranked among the world’s major libraries. It has the second richest library collection in the Russian Federation, a treasury of national heritage, and is the All-Russian Information, Research and Cultural Center. Over the course of its history, the Library has aimed for comprehensive acquisition of the national printed output and has provided free access to its collections. It should not be confused with the Russian State Library, located in Moscow.

History

Establishment

The Imperial Public Library was established in 1795 by Catherine the Great. It was based on the Załuski Library, the famous Polish national library built by Bishop Zalusky in Warsaw, which had been seized by the Russians in 1794.[2]

The idea of a public library in Russia emerged in the early 18th century[3] but did not take shape until the arrival of the Russian Enlightenment. The plan of a Russian public library was submitted to Catherine in 1766 but the Empress did not approve the project for the imperial library until 27 May [O.S. 16 May] 1795, eighteen months before her death. A site for the building was found at the corner of Nevsky Avenue and Sadovaya Street, right in the center of the Russian Imperial capital. The construction work began immediately and lasted for almost fifteen years. The building was designed in a Neoclassical style by architect Yegor Sokolov (built between 1796–1801).

The cornerstone of the foreign-language department came from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the form of Załuski's Library (420,000 volumes), seized in part by the Russian government at the time of the partitions, though many volumes were lost en route to theft by Russian soldiers who sold them for profit.[4] The Polish-language books from the library (numbering some 55,000 titles) were returned to Poland by the Russian SFSR in 1921.[5]

For five years after its foundation, the library was run by Comte Marie-Gabriel-Florent-Auguste de Choiseul-Gouffier. The stocks were arranged according to a specially compiled manual of library classification.[6] In 1810, Emperor Alexander I approved Russia’s first library law stipulating, among other things, that two legal copies of all printed matter in Russia be deposited in the Library.[7]

The Library was to be opened for the public in 1812 but, as the more valuable collections had to be evacuated because of Napoleon’s invasion, the inauguration was postponed for two years.

Under Count Alexander Stroganov, who managed the library during the first decade of the 19th century, the Rossica project was inaugurated, a vast collection of foreign books touching on Russia. It was Stroganov who secured for the library some of its most invaluable treasures, namely the Ostromir Gospel, the earliest book written in the Old East Slavic dialect of Church Slavonic (which was to eventually develop into the Russian language), and the Hypatian Codex of the Russian Primary Chronicle.

1814-1917

The Imperial Public Library was inaugurated on 14 January [O.S. 2 January] 1814 in the presence of Gavrila Derzhavin and Ivan Krylov. Over 100 thousand titles were issued to the visitors in the first three decades, and the second Library building (designed by Carlo Rossi) facing the Catherine Garden was erected between 1832-1835 to accommodate the growing collections.

The library's third, and arguably most famous, director was Aleksey Olenin (1763–1843). His 32-year tenure at the helm, with Sergey Uvarov serving as his deputy, raised the profile of the library among Russian intellectuals. The library staff included prominent men of letters and scholars like Ivan Krylov, Konstantin Batyushkov, Nikolay Gnedich, Anton Delvig, Mikhail Zagoskin, Alexander Vostokov, and Father Ioakinf, to name but a few.

Librarianship progressed to a new level in the 1850s. The reader community grew several times, enlarged by common people. At the same time, many gifts of books were offered to the library. Consequently, collection growth rates in the 1850s were five times higher than the annual growth rate of five thousand new acquired during the first part of the century. In 1859, Vasily Sobolshchikov prepared for the library the first national manual of library science entitled Public Library Facilities and Cataloguing.[8] By 1864, the Public Library held almost 90 per cent of all Russian printed output.

The influx of new visitors required a larger reading room in the new building closing the library court along the perimeter (designed by Sobolshikov, built in 1860—62). The visitors were offered such novelties as continuous reading room service by library staff members, a reference desk, printed catalogues and guide books, lists of new acquisitions, and longer hours of service in the reading room (10 a.m. to 9 p.m).

An avalanche-like growth of attendance persisted in the second part of the 19th century. Library cards and attendance grew tenfold between 1860 and 1913. The public principle triumphed when the class barriers maintained until the mid-19th century were abolished and the petty bourgeois, peasants and even women were often seen among the visitors. Women were also employed by the Library but only as volunteer members rather than formal staff.

From 1849 to 1861 the library was managed by Count Modest von Korff (1800–76), who had been Alexander Pushkin's school-fellow at the Lyceum. Korff and his successor, Ivan Delyanov, added to the library's collections some of the earliest manuscripts of the New Testament (the Codex Sinaiticus from the 340s), the Old Testament (the so-called Leningrad Codex), and one of the earliest Qur'ans (the Uthman Qur'an from the mid-7th century).

The Library’s role was adapted to changing conditions requiring close contacts with universities, scientific societies, leading research centers and major international libraries. The Public library engaged eminent scholars and cultural workers, and research groups were formed to study precious books and manuscripts.

The Library continued to build a comprehensive collection of national publications. The growing collections were located in a new building (designed by E.S. Vorotilov, 1896—1901). By 1913, the Library held one million Russian books (total collections comprising three million titles), emerging as one of the world’s great libraries and the richest manuscript collection in Russia.

20th century

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, the institution was placed under the management of Ernest Radlov and Nicholas Marr, although its national preeminence was relinquished to the Lenin State Library in Moscow. The library was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour in 1939 and remained open during the gruesome Siege of Leningrad. In 1948, the Neoclassical campus of the Catherine Institute on the Fontanka Embankment (Giacomo Quarenghi, 1804–07) was assigned to the library. By 1970, the Library contained more than 17,000,000 items. The modern building for the book depository was erected on Moskovsky Prospekt in the 1980s and 1990s.

The National Library began a large-scale digitization project at the end of the 20th century. By 2012 the Library, along with its counterpart in Moscow, had around 80,000 titles available electronically.[9]

- Highlights of the library

St. Petersburg Bede (746)

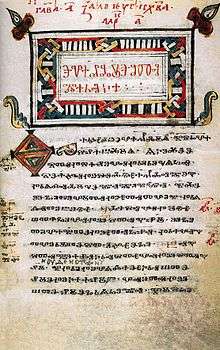

St. Petersburg Bede (746) Trebizond Gospel (10th century)

Trebizond Gospel (10th century) Codex Zographensis (c. 1000)

Codex Zographensis (c. 1000) Leningrad Codex (c. 1008)

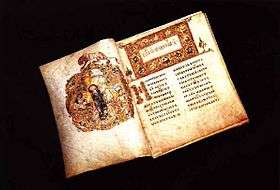

Leningrad Codex (c. 1008) Ostromir Gospel (1056)

Ostromir Gospel (1056) Spiridon Psalter (1397)

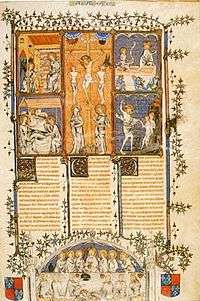

Spiridon Psalter (1397) Guyart de Moulin's Bible Historiale (1350s)

Guyart de Moulin's Bible Historiale (1350s)- Simon Marmion's Grandes Chroniques de France (1450s)

Breviary of Mary Stuart (1490s)

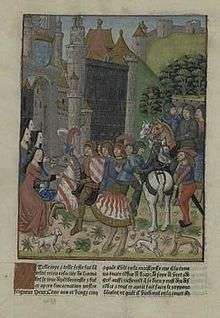

Breviary of Mary Stuart (1490s) Lancelot du Lac (c. 1500)

Lancelot du Lac (c. 1500)

References

- ↑ Legal Deposit Law

- ↑ Stuart (1989) p 201

- ↑ Императорская Публичная библиотека за сто лет [A Hundred Years of Imperial Public Library], 1814–1914. SPb : print. by V.F. Kirschbaum, 1914. P. 1.

- ↑ Малый энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона, published in the Imperial Russia in the early 1900s

- ↑ Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd. edition

- ↑ Оленин А. Н. Опыт нового библиографического порядка для Санкт-Петербургской Публичной библиотеки [Tentative bibliographical scheme for the Public Library in Saint Petersburg]. SPb, 1809. 8, 112 p.

- ↑ Положение о управлении имп. Публичною библиотекою // Акты, относящиеся до нового образования Императорской библиотеки... [ Imp. Library administration/ In: Acts concerning the foundation of Imperial Library...] [SPb.], 1810. pp. 8—11.

- ↑ Собольщиков В.И. Об устройстве общественных библиотек и составлении их каталогов [Sobolshikov V.I. Public library structure and cataloguing]. SPb., 1859. 6, 56 p.

- ↑ Editors, Slavica Publishers. "Russian History and the Digital Age". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 13 (4): 765–768.

Bibliography

- Stuart, Mary. "'A Potent Lever for Social Progress': The Imperial Public Library in the Era of the Great Reforms." Library Quarterly (1989): 199-222. in JSTOR

- Stuart, Mary. "The evolution of librarianship in Russia: The librarians of the imperial public library, 1808-1868." Library Quarterly (1994): 1-29. in JSTOR

- Stuart, Mary. "Creating culture: the Rossica collection of the imperial public library and the construction of national identity." Libraries & culture (1995): 1-25. in JSTOR

- Stuart, Mary. "Creating a National Library for the Workers' State: The Public Library in Petrograd and the Rumiantsev Library under Bolshevik Rule." Slavonic and East European Review 72.2 (1994): 233-258. JSTOR

In Russian

- История Государственной ордена Трудового Красного Знамени Публичной библиотеки имени М. Е. Салтыкова-Щедрина. — Ленинград: Лениздат, 1963. — 435 с., [15] л. ил.

- История Библиотеки в биографиях её директоров, 1795—2005 / Российская национальная библиотека. — Санкт-Петербург, 2006. — 503, [1] с.: ил. — ISBN 5-8192-0263-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Russian National Library. |

- Official site of the library

- Russian National Library on the Fontanka Embankment

- Russian National Library on the Moscow Prospect

- The personal library of Voltaire as exhibited in the RNL