SS Eastland

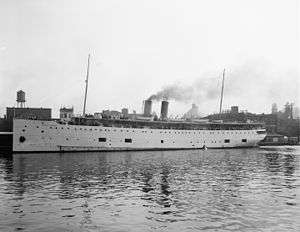

The SS Eastland docked | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Eastland |

| Owner: | Michigan Steamship Company |

| Route: | South Haven, Michigan, to Chicago, Illinois, route |

| Ordered: | October 1902 |

| Builder: | Jenks Ship Building Company |

| Launched: | May 6, 1903 |

| Christened: | May 1903 by Francis Elizabeth Stufflebeam |

| Maiden voyage: | July 16, 1903 |

| Nickname(s): | "Speed queen of the Great Lakes" |

| Fate: | Sold in 1905 to the Michigan Transportation Company |

| Name: | Eastland |

| Owner: | Michigan Transportation Company |

| Operator: | Chicago-South Haven Line |

| Route: | South Haven – Chicago route |

| Fate: | Sold August 5, 1906, to the Lake Shore Navigation Company of Cleveland, Ohio |

| Name: | Eastland |

| Owner: | Lake Shore Navigation Company of Cleveland, Ohio |

| Route: | Cleveland-Cedar Point route |

| Fate: | Sold in 1909 to the Eastland Navigation Company of Cleveland, Ohio |

| Name: | Eastland |

| Owner: | Eastland Navigation Company of Cleveland, Ohio |

| Route: | Cleveland-Cedar Point route |

| Fate: | Sold on June 1, 1914 to the St. Joseph-Chicago Steamship Company of St. Joseph, Michigan |

| Name: | Eastland |

| Owner: | St. Joseph-Chicago Steamship Company of St. Joseph, Michigan |

| Route: | St. Joseph, Michigan, to Chicago route |

| Fate: | Raised after accident on October 1915 and sold at auction on December 20, 1915 to Captain Edward A. Evers, sold on November 21, 1917 to the Illinois Naval Reserve. |

| Name: | USS Wilmette |

| Acquired: | November 21, 1917 |

| Commissioned: | September 20, 1918 |

| Recommissioned: |

|

| Decommissioned: |

|

| Renamed: | Wilmette on February 20, 1918 |

| Reclassified: |

|

| Struck: | December 19, 1945 |

| Honors and awards: |

|

| Fate: | Sold for scrap on October 31, 1946 to Hyman Michaels Company of Chicago and scrapped, scrapping completed in 1947 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Passenger Ship |

| Type: | Steamship |

| Tonnage: | 1,961 gross |

| Displacement: | 2,600 (estimated) |

| Length: | 265 ft |

| Beam: | 38 ft 2 in |

| Draft: | 19 ft 6 in |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | Two shafts |

| Speed: | 16.5 knots |

| Capacity: | As Eastland: 2,752 passengers |

| Complement: | As USS Wilmette: 209 |

| Armament: |

|

| Notes: |

|

The SS Eastland was a passenger ship based in Chicago and used for tours. On July 24, 1915, the ship rolled over while tied to a dock in the Chicago River.[1] A total of 844 passengers and crew were killed in what was the largest loss of life from a single shipwreck on the Great Lakes.[1][2]

Following the disaster, the Eastland was salvaged and sold to the United States Navy. After restorations and modifications, the Eastland was designated as a gunboat and renamed the USS Wilmette. She was used primarily as a training vessel on the Great Lakes, and was scrapped following World War II.

Construction

The ship was commissioned in 1902 by the Michigan Steamship Company and built by the Jenks Ship Building Company of Port Huron, Michigan.[3] In April 1903, the ship was named by Mrs. David Reid of South Haven, Michigan. She received a prize of $10 and a one-season pass on the ship. The ship was named in May, immediately before its inaugural voyage.

History

Early problems

Following its construction, the Eastland was discovered to have design flaws, making it susceptible to listing. The ship was top-heavy with its center of gravity being too high. This became evident when passengers congregated en masse on the upper decks. In July 1903, a case of overcrowding caused the Eastland to list with water flowing up one of the ship's gangplanks. The situation was quickly rectified, but this was the first of many incidents. Later in the same month, the stern of the ship was damaged when it was backed into the tugboat George W. Gardner. In August 1906, another incident of listing occurred which resulted in the filing of complaints against the Chicago-South Haven Line which had purchased the ship earlier that year.

Mutiny on the Eastland

On August 14, 1903, while on a cruise from Chicago to South Haven, Michigan, six of the ship's firemen refused to stoke the fire for the ship's boiler. They claimed that they had not received their potatoes for a meal.[4] When they refused to return to the fire hole, Captain John Pereue ordered the six men arrested at gun point. Firemen George Lippen and Benjamin Myers, who were not a part of the group of six, stoked the fires until the ship reached harbor. Upon the ship's arrival in South Haven, the six men – Glenn Watson, Mike Davern, Frank La Plarte, Edward Fleming, Mike Smith, and William Madden – were taken to the town jail and charged with mutiny. Shortly thereafter, Captain Pereue was replaced.[4]

The Eastland disaster

On July 24, 1915, Eastland and four other Great Lakes passenger steamers, Theodore Roosevelt, Petoskey, Racine, and Rochester, were chartered to take employees from Western Electric Company's Hawthorne Works in Cicero, Illinois, to a picnic in Michigan City, Indiana.[5][6] This was a major event in the lives of the workers, many of whom could not take holidays. Many of the passengers on the Eastland were Czech immigrants from Cicero; 220 of them perished.

In 1915, the new federal Seamen's Act had been passed because of the RMS Titanic disaster three years earlier. The law required retrofitting of a complete set of lifeboats on the Eastland, as on many other passenger vessels.[7] This additional weight may have made the Eastland more dangerous as it potentially worsened the already severe problem of being top-heavy. Some argued that other Great Lakes ships would suffer from the same problem.[7] Nonetheless, it was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson. The Eastland was already so top-heavy that she had special restrictions concerning the number of passengers that could be carried. Prior to that, in June 1914, the Eastland had again changed hands, this time bought by the St. Joseph and Chicago Steamship Company, with Captain Harry Pedersen appointed the ship's master.

On the fateful morning, passengers began boarding the Eastland on the south bank of the Chicago River between Clark and LaSalle Streets around 6:30 am, and by 7:10 am, the ship had reached its capacity of 2,572 passengers. The ship was packed, with many passengers standing on the open upper decks, and began to list slightly to the port side (away from the wharf). The crew attempted to stabilize the ship by admitting water to its ballast tanks, but to little avail. Sometime in the next 15 minutes, a number of passengers rushed to the port side, and at 7:28 am, Eastland lurched sharply to port, and then rolled completely onto her side, coming to rest on the river bottom, which was only 20 feet (6.1 m) below the surface. Many other passengers had already moved below decks on this relatively cool and damp morning to warm up before the departure. Consequently, hundreds were trapped inside by the water and the sudden rollover; others were crushed by heavy furniture, including pianos, bookcases, and tables. Although the ship was only 20 ft from the wharf, and in spite of the quick response by the crew of a nearby vessel, the Kenosha, which came alongside the hull to allow those stranded on the capsized vessel to leap to safety, a total of 844 passengers and four crew members died in the disaster.

The bodies of the victims were taken to various temporary morgues set up in the area for identification; by afternoon, the remaining unidentified bodies were consolidated at the 2nd Regiment Armory,[5] on the site which has since been transformed into Harpo Studios, the sound stage for The Oprah Winfrey Show and other productions.[8][9]

One of the people who were scheduled to be on Eastland was 20-year-old George Halas, the American football pioneer, who was delayed leaving for the dock, and arrived after the ship had capsized.[10] Despite stories to the contrary, no reliable evidence indicates Jack Benny was on board the Eastland or scheduled to be on the excursion; possibly the basis for this report was that the Eastland was a training vessel during World War I and Jack Benny received his training on the Great Lakes naval base, where the Eastland was stationed.

The first known film footage taken of the recovery efforts was discovered and then released in early 2015 by a graduate student at the University of Illinois at Chicago.[11]

Marion Eichholz, the last known survivor of the capsizing, died on November 24, 2014, at the age of 102.[12]

Eastland disaster and the media

Writer Jack Woodford witnessed the disaster and gave a first-hand account to the Herald and Examiner, a Chicago newspaper. In his autobiography, Woodford writes:

And then movement caught my eye. I looked across the river. As I watched in disoriented stupefaction a steamer large as an ocean liner slowly turned over on its side as though it were a whale going to take a nap. I didn't believe a huge steamer had done this before my eyes, lashed to a dock, in perfectly calm water, in excellent weather, with no explosion, no fire, nothing. I thought I had gone crazy.

Newspapers played a significant part in not only covering the Eastland disaster, but also creating the public memory of the catastrophe. The newspapers’ purpose, audience, and political and business connections influenced the newspapers to publish articles to focus on who was to blame and why the Eastland capsized. Consequently, the articles influenced how the court cases proceeded, and contributed to a debate between Western Electric Company and its workers regarding how the company responded to the catastrophe. Furthermore, the newspaper articles paved the way for the event to be used as a platform to discuss broader issues of the Progressive Era, including greed, corruption, capitalism, and sensationalized journalism.

Carl Sandburg, then better known as a journalist than a poet, wrote an angry account accusing regulators of turning a blind eye to safety issues and claimed that many of the workers were there on company orders for a staged picnic.[13] Sandburg also wrote a poem, "The Eastland", that contrasts the disaster with the mistreatment and poor health of the lower classes at the time. After first listing the quick, murderous horrors of the disaster, then surveying the slow, murderous horrors of extreme poverty, Sandburg concludes by comparing the two: "I see a dozen Eastlands/Every morning on my way to work/And a dozen more going home at night."[14] The poem was too harsh for publication when written but was eventually released as part of a collection of poems in 1993.[15]

The Eastland disaster was incorporated into the 1999 series premiere of the Disney Channel original series So Weird. In the episode, teenaged paranormal enthusiast Fiona Phillips (actress Cara DeLizia) encounters the ghost of a young boy who drowned during the capsizing while exploring a nightclub near the Chicago River, and attempts to figure out why he has contacted her.[16]

In 2012, Chicago's Lookingglass Theatre produced an original musical about the disaster entitled Eastland: A New Musical and written by Andy White.[17]

Inquiry and indictments

A grand jury indicted the president and three other officers of the steamship company for manslaughter, and the ship's captain and engineer for criminal carelessness, and found that the disaster was caused by "conditions of instability" caused by any or all of overloading of passengers, mishandling of water ballast, or the construction of the ship.[18]

Federal extradition hearings were held to compel the six indicted men to come from Michigan to Illinois for trial. During the hearings, principal witness Sidney Jenks, head of the shipbuilding company that built the Eastland, testified that her first owners wanted a fast ship to transport fruit, and he designed one capable of making 20 mph (32 km/h) and carrying 500 passengers. Defense counsel Clarence Darrow asked whether he had ever worried about the conversion of ship into a passenger steamer with a capacity of 2,500 or more passengers. Jenks replied, "I had no way of knowing the quantity of its business after it left our yards... No, I did not worry about the Eastland." Jenks testified that an actual stability test of the ship never occurred, and stated that after tilting to an angle of 45° at launching, "it righted itself as straight as a church, satisfactorily demonstrating its stability."[19]

The court refused extradition, holding the evidence was too weak, with "barely a scintilla of proof" to establish probable cause to find the six guilty. The court reasoned that the four company officers were not aboard the ship, and that every act charged against the captain and engineer was done in the ordinary course of business, "more consistent with innocence than with guilt." The court also reasoned that the Eastland "was operated for years and carried thousands safely", and that for this reason no one could say that the accused parties were unjustified in believing the ship seaworthy.[20]

Second life as USS Wilmette

After the Eastland was raised on August 14, 1915, she was sold to the Illinois Naval Reserve and recommissioned as USS Wilmette stationed at Great Lakes Naval Base. She was converted to a gunboat, renamed Wilmette on February 20, 1918, and commissioned on September 20, 1918, with Captain William B. Wells in command.[21] Commissioned late in World War I, Wilmette had no combat service. She trained sailors and engaged in normal upkeep and repairs until placed in ordinary at Chicago on July 9, 1919, retaining a 10-man caretaker crew on board. On June 29, 1920, the gunboat was returned to full commission, with Captain Edward A. Evers, USNRF, in command.[21]

On June 7, 1921, the Wilmette was given the task of sinking UC-97, a German U-boat surrendered to the United States after World War I.[22] The guns of the Wilmette were manned by Gunner's Mate J.O. Sabin, who had fired the first American shell in World War I, and Gunner's Mate A.F. Anderson, the man who fired the first American torpedo in the conflict.[23] For the remainder of her 25-year career, the gunboat served as a training ship for naval reservists in the 9th, 10th, and 11th Naval Districts. She made voyages along the shores of the Great Lakes carrying trainees assigned to her from the Naval Station Great Lakes in Illinois. Wilmette remained in commission, carrying out her reserve training mission until she was placed "out of commission, in service," on February 15, 1940.

Given hull designation IX-29 on February 17, 1941, she resumed training duty at Chicago on March 30, 1942, preparing armed guard crews for duty manning the guns on armed merchantmen. That assignment continued until the end of World War II in Europe obviated measures to protect trans-Atlantic merchant shipping from German U-boats.

During August 1943, the Wilmette was given the honor of transporting President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Admiral William D. Leahy, James F. Byrnes, and Harry Hopkins on a 10-day cruise to McGregor and Whitefish Bay to plan war strategies.[24]

On April 9, 1945, she was returned to full commission for a brief interval. Wilmette was decommissioned on November 28, 1945, and her name was struck from the Navy list on December 19, 1945. In 1946, the Wilmette was offered up for sale. Finding no takers, on October 31, 1946, she was sold to the Hyman Michaels Company for scrapping, which was completed in 1947.[21]

Memorials

A marker commemorating the accident was dedicated on June 4, 1989. This marker was reported stolen on April 26, 2000, and a replacement marker was installed and rededicated on July 24, 2003.

Plans exist for a permanent outdoor exhibit with the proposed name "At The River's Edge". This exhibit would be located along the portion of the Chicago Riverwalk adjacent to the waters where the Eastland disaster occurred. The exhibit is planned to consist of six displays each containing two unique panels which will serve to illustrate the tragedy through text and high-resolution images.[25]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Eastland Memorial Society". Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- ↑ Baillod, Brendon. "Introduction". The Wreck of the Steamer Lady Elgin. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ↑ "Jenks Shipbuilding, Port Huron MI". Shipbuilding History. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- 1 2 "History: August 14, 1903". Eastland (1903). Maritime Quest. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- 1 2 "Eastland Memorial Edition". Western Electric News. August 1915. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ↑ Hilton, George W (1995). Eastland: Legacy of the Titanic. Standford, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 93.

- 1 2 "The Prophecy". The Eastland – Lake Erie. Eastland Memorial Society. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ↑ "The Oprah Winfrey Show trivia", www.oprah.com. Retrieved on 2008-07-28.

- ↑ "ITB: Eastland ghost stories". Chicago Bears. October 29, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

He decided they needed to set up a consolidated, temporary morgue. They did at the 2nd Regiment Armory building, which later became the studios for Oprah Winfrey.

- ↑ "ITB: Halas escapes Eastland Disaster". Chicago Bears. October 29, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Meredith (Feb 8, 2015). "First known film clips emerge of 1915 Eastland disaster". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 12, 2015.

- ↑ "Last Survivor of 1915 Eastland Disaster Dies". Chicago Tribune. December 14, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ↑ Sandburg, Carl (September 1915). "Looking 'em over". The International Socialist Review. XVI (3): 132–137.

- ↑ "Eastland".

- ↑ Sandburg, Carl (1993). Hendrik, George; Hendrik, Willene, eds. Billy Sunday and Other Poems. Harcourt Brace & Company. p. xiii.

- ↑ AwesomeTVShows. "So Weird 1x01 - Family Reunion". Dailymotion. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ Ingram, Bruce (2012-06-28). "Musical Memorial for a Chicago Tragedy". Deerfield Review. Glenview, IL: Pioneer Press. pp. 98=B.

- ↑ "SIX ARE INDICTED FOR EASTLAND LOSS; President of the Company, Captain, and Engineer Among Those Held for Disaster.". The New York Times. August 11, 1915.

- ↑ "EASTLAND NEVER TESTED.; Builder of Ill-Fated Ship Says She Was Designed to Carry 500". The New York Times. January 23, 1916.

- ↑ "Nation Loses Point in Eastland Case; Court Refuses Application for Removal of Indicted Persons to Jurisdiction of Illinois.". The New York Times. February 18, 1916.

- 1 2 3 "Wilmette". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. United States Navy. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ↑ "The UC-97". Eastland Disaster Historical Society. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ↑ "USS Wilmette". Eastland Memorial Society. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- ↑ "History:Aug.1943". Eastland (1903) Builder's Data. Maritime Quest. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- ↑ "At The River's Edge A permanent outdoor Eastland Disaster exhibit". Eastland Disaster Historical Society. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

Further reading

- Michael McCarthy, Ashes Under Water: The SS Eastland and the Shipwreck that Shook America, Lyons Press 2014. ISBN 978-0762793280

- Jay Bonansinga, The Sinking of the Eastland: America's Forgotten Tragedy, Citadel Press 2004. ISBN 0-8065-2628-9

- George Hilton, Eastland: Legacy of the Titanic, Stanford University Press 1997. ISBN 0-8047-2801-1

- Ted Wachholz, The Eastland Disaster, Arcadia Publishing 2005. ISBN 0-7385-3441-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eastland (ship, 1903). |

- Eastland Disaster Historical Society

- Maritimequest Eastland Photo Gallery

- Eastland Memorial Society

- Chicago Tribune Photographs

- Eastland Disaster Film Archive Videos

- Bloomington witness to Eastland disaster - Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois newspaper)