Holy Chalice

In Christian tradition the Holy Chalice is the vessel which Jesus used at the Last Supper to serve the wine. The vessel is referred to in the synoptic gospels as ποτήριον ("cup, drinking vessel"). The celebration of the Eucharist in Christian churches and communities retains the original elements of the Last Supper, the bread and the cup or chalice, with the celebrant using the words of Jesus, as recorded in the Gospels. The Holy Chalice in the form of the "Holy Grail" became a topos in Arthurian romance in the high medieval period. In Roman Catholic relic veneration of the later medieval period, two artifacts, one kept in Genoa and the other in Valencia, were identified as the Holy Chalice.

The Last Supper

The Gospel of Matthew (26:27-29) says:[1]

And He took a cup and when He had given thanks He gave it to them saying "Drink this, all of you; for this is My blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you, I shall not drink again of the fruit of the vine until I drink it new with you in My Father's kingdom."

This incident, traditionally known as the Last Supper, is also described by the gospel writers, Mark and Luke, and by the Apostle Paul in I Corinthians. With the preceding description of the breaking of bread, it is the foundation for the tradition of the Eucharist or Holy Communion, celebrated regularly in many Christian churches. The Bible makes no mention of the cup except within the context of the Last Supper and gives no significance whatsoever to the object itself.

St. John Chrysostom (347–407 AD) in his homily on Matthew asserted:

The table was not of silver, the chalice was not of gold in which Christ gave His blood to His disciples to drink, and yet everything there was precious and truly fit to inspire awe.

Herbert Thurston in the Catholic Encyclopedia (1908) concluded that:

No reliable tradition has been preserved to us regarding the vessel used by Christ at the Last Supper. In the sixth and seventh centuries pilgrims to Jerusalem were led to believe that the actual chalice was still venerated in the church of the Holy Sepulchre, having within it the sponge which was presented to Our Saviour on Calvary.

No reliable tradition has been preserved regarding the vessel used by Christ at the Last Supper.[2]

According to one tradition, Saint Peter brought it to Rome, and passed it on to his successors (the Popes). In 258, when Christians were being persecuted by Emperor Valerian and the Romans demanded that relics be turned over to the government, Pope Sixtus II instead gave the cup to one of his deacons, Saint Lawrence, who passed it to a Spanish soldier, Proselius, with instructions to take it to safety in Lawrence's home country of Spain.

Medieval tradition

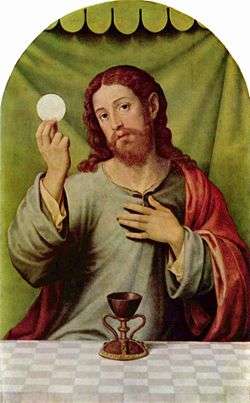

Iconography

The iconic significance of the Chalice grew during the Early Middle Ages. Depictions of Jesus praying in the Garden of Gethsemane, such as that in the fourteenth-century frescoes of the church at the Öja, Gotland (illustration, right), show a prefigured apparition of the Holy Chalice that stands at the top of the mountain, illustrating the words "Let this cup be taken from me". Together with the halo-enveloped Hand of God and the haloed figure of Jesus, the halo image atop the chalice, as if of a consecrated communion wafer, completes the Trinity by embodying the Holy Spirit.

Holy Grail

The Holy Grail appears as a miraculous artifact in Arthurian literature in the 12th century, and is soon associated with the Holy Chalice.

The "Grail" became interwoven with the legend of the Holy Chalice. The connection of the Holy Chalice with Joseph of Arimathea dates from Robert de Boron's Joseph d'Arimathie (late 12th century). The fully developed "Grail legend" of the 13th century identifies the Holy Grail with the Holy Chalice used in the Last Supper and later used to collect Christ's blood, brought to Hispania by Joseph of Arimathea. It has been suggested that this form of the legend combines elements of a magical cauldron from Celtic mythology with Christian legend surrounding the Holy Chalice and the Eucharist.

Medieval relics

In the account of Arculf, a 7th-century Anglo-Saxon pilgrim, mention is made of a chalice venerated as the one used in the Last Supper in a chapel near Jerusalem. This is the only mention of the veneration of such a relic in the Holy Land.[3]

Two artifacts were claimed as the Holy Chalice in Western Christianity in the later medieval period. The first is the santo cáliz, an agate cup in the Cathedral of Valencia, first mentioned in the 12th century. The other is the Santo Cation in Genoa Cathedral, a flat dish made of green glass; this latter artifact was recovered from Caesarea in 1101, but it was not identified as the Holy Chalice until much later, towards the end of the 13th century.

Valencia Chalice

The other surviving Holy Chalice vessel is the santo cáliz, an agate cup in the Cathedral of Valencia. It is preserved in a chapel consecrated to it, where it still attracts the faithful on pilgrimage. The artifact has seemingly never been accredited with any supernatural powers.

The cup is made of dark red agate which is mounted by means of a knobbed stem and two curved handles onto a base made from an inverted cup of chalcedony. The agate cup is about 9 centimeters (3.5 inches) in diameter and the total height, including base, is about 17 centimetres (7 inches) high. The lower part has Arabic inscriptions. It was most likely produced in a Palestinian or Egyptian workshop between the 4th century BC and the 1st century AD.[4]

It is kept together with an inventory list on vellum, said to date from AD 262, that accompanied a lost letter which detailed state-sponsored Roman persecution of Christians that forced the church to split up its treasury and hide it with members, specifically the deacon Saint Lawrence. The physical properties of the Holy Chalice are described and it is stated the vessel had been used to celebrate Mass by the early Popes succeeding Saint Peter.

The first explicit inventory reference to the present Chalice of Valencia if found in an inventory of the treasury of the monastery of San Juan de la Peña drawn up by Don Carreras Ramírez, Canon of Zaragoza, on the 14th of December 1134. The Chalice is described as the vessel in which "Christ Our Lord consecrated his blood" (En un arca de marfil está el Cáliz en que Cristo N. Señor consagró su sangre, el cual envió S. Lorenzo a su patria, Huesca).

Reference to the chalice is made in 1399, when it was given by the monastery of San Juan de la Peña to king Martin I of Aragon in exchange for a gold cup.

Pope John Paul II himself celebrated mass with the Holy Chalice in Valencia in November 1982. In July 2006, at the closing Mass of the 5th World Meeting of Families in Valencia, Pope Benedict XVI also celebrated with the Holy Chalice, on this occasion saying "this most famous chalice" ( hunc praeclarum Calicem), words in the Roman Canon said to have been used for the first popes until the 4th century in Rome.

Bennett (2004) argues for the chalice's authenticity, tracing its history via Saint Peter's journey to Rome, Pope Sixtus II, Saint Lawrence, and finally to the Monastery of San Juan de la Peña whence it was acquired by King Martin I of Aragon in 1399. Bennett presents as historical evidence a 17th-century Spanish text entitled Life and Martyrdom of the Glorious Spaniard St. Laurence from a monastery in Valencia, which is supposed to be a translation of a 6th-century Latin Vita of Saint Laurence, written by Donato, an Augustinian monk who founded a monastery in the area of Valencia, which contains circumstantial details of the life and details surrounding the transfer of the Chalice to Spain.[5]

Genoa Chalice

The Sacro Catino, kept in Genoa Cathedral, is a hexagonal dish of the Roman era made of green Egyptian glass, some 9 cm high and 33 cm across. It was taken to Genoa by Guglielmo Embriaco as part of the spoils from the conquest of Caesarea in 1101. William of Tyre (10.16) describes it as a "vessel of the most green colour, in the shape of a serving dish" (vas coloris viridissimi, in modum parapsidis formatum) which the Genuese thought to be made of emerald, and accepted as their share of the spoils. William states that the Genoese were still exhibiting the bowl, insisting on its miraculous properties due to its being made of emerald, in his own day (Unde et usque hodie transeuntibus per eos magnatibus, vas idem quasi pro miraculo solent ostendere, persuadentes quod vere sit, id quod color esse indicat, smaragdus), the implication being that emerald was thought to have miraculous properties of their own in medieval lore and not that the bowl was thought of as a holy relic. The Sacro Catino would later become identified as the Holy Grail. The first explicit claim to this effect is found in the Chronicon by Jacobus de Voragine, written in the 1290s.[6] Pedro Tafur, who visited Genoa in 1436, reported that the Holy Grail, "made of a single emerald" is kept in Genoa Cathedral.[7] The bowl was seized and taken to Paris by Napoleon in 1805, and it was damaged when it was returned to Genoa in 1816.

Modern candidates

With the rising popularity of the Grail legend in 19th-century Romanticism, a number of other artifacts of greater or lesser notability came to be identified with the "Holy Grail" or "Holy Chalice".[8]

The Chalice of Doña Urraca has not traditionally been associated with the Holy Chalice, but was proposed as such in a 2014 publication. The "Antioch Chalice" is an artifact discovered in Antioch in 1910 which was briefly marketed as the "Holy Chalice", but it is most likely a lamp in a style of the 6th century.[9]

Chalice of Doña Urraca

The Chalice of Doña Urraca is an artifact kept in the Basilica of San Isidoro in León, Spain.[10] The connection of this artifact to the Holy Grail was made in the 2014 book Los Reyes del Grial, which develops the hypothesis that this artifact had been taken by Egyptian troops following the invasion of Jerusalem and the looting of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, then given by the Emir of Egypt to the Emir of Denia, who in the 11th century gave it to the Kings of Leon in order for them to spare his city in the Reconquista.[11]

Antioch Chalice

The silver-gilt object originally identified as an early Christian chalice is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It was apparently made at Antioch in the early 6th century and is of double-cup construction, with an outer shell of cast-metal open work enclosing a plain silver inner cup. When it was first recovered in Antioch in 1910, it was touted as the Holy Chalice, an identification the Metropolitan Museum characterizes as "ambitious". It is no longer identified as a chalice, having been identified by experts at Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, believed to be a standing lamp, of a style of the 6th century.[12]

Nanteos Cup

The Nanteos Cup is a medieval wood mazer bowl, held for many years at Nanteos Mansion, Rhydyfelin, near Aberystwyth in Wales.[13] It is recorded as having been attributed miraculous powers of healing in the late 19th century, and tradition apparently held it had been made from a piece of the True Cross at the time, but it came to be identified as the Holy Chalice in the early 20th century. [14]

See also

References

- ↑ Bible gateway, Matthew 26:27

- ↑ Thurston, Herbert. "Chalice." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 27 Jul. 2013

- ↑ De locis sanctis; the chapel was located between the basilica of Golgotha and the Martyrium. The relic is described as a two-handled silver chalice with the measure of a Gaulish pint. Arculf kissed his hand and reached through an opening of the perforated lid of the reliquary to touch the chalice. He said that the people of the city flocked to it with great veneration.

- ↑ Antonio Beltrán (1960) Report in the Denver Catholic Register "Spanish academic revives speculation about authenticity of the Holy Grail", October 1999

- ↑ Bennett, Janice, Saint Laurence and the Holy Grail (self-published through the Catholic Ignatius Press), 2004.

- ↑ Marica, Patrizia, Museo del Tesoro Genoa, Italy (2007), 7–12. Juliette Wood, The Holy Grail: History and Legend (2012).

- ↑ "The great church is called San Lorenzo, and it is very remarkable, particularly the porch. They keep in it the Holy Grail, which is made of a single emerald and is indeed a marvellous relic," Pedro Tafur, Andanças e viajes.

- ↑ A 2014 Guardian article on the Chalice of Doña Urraca mentions in passing that "In Europe alone there are 200 supposed holy grails, the Spanish researchers admitted." "Crowds flock to Spanish church after holy grail claim". The Guardian. London. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ Eisen, Gustavus A., The great chalice of Antioch, New York, Fahim Kouchakji, 1933. Eisen, Gustavus A., The great chalice of Antioch, on which are depicted in sculpture the earliest known portraits of Christ, apostles and evangelists, New York, Kouchakji frères, 1923. Metropolitan Museum: Antioch Chalice

- ↑ Historians claim Holy Grail is in church in Leon, northern Spain by Bob Fredericks (News.com.au, 1 April 2014)

- ↑ Fredericks, Bob (March 31, 2014). "Historians claim to have recovered Holy Grail". nypost.com. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- ↑ Metropolitan Museum

- ↑ Barber, Richard (2 December 2004). The Holy Grail: The History of a Legend. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-140-26765-5.

- ↑ "The Nanteos Cup: Curious Relic in North Cardiganshire: Remarkable instance of faith cure". Western Mail (8255). Cardiff. 5 November 1895 – via 19th Century British Newspapers. Thorpe, Vanessa (26 January 2014). "Holy Grail quest set to bring tourist boom to 'magical' Nanteos House in Wales". The Observer. London. Retrieved 6 August 2014. Wood, Juliette (5 March 2013). "The Phantom Cup that Comes and Goes: The Story of the Holy Grail". Gresham College. London. Lecture given at the Museum of London. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- Salvador Antuñano Alea, Truth and Symbolism of Holy Grail: Revelations Surrounding Valencia's Sacred Chalice (in Spanish, with a prologue by Archbishop Agustin Garcia Gasco of Valencia), 1999

- Strzygowski, Josef, L'ancien art chrétien de Syrie, Paris, E. de Boccard, 1936.

- Relics of the Passion, 2005, History Channel video documentary

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Chalice (illustration of the Holy Chalice of Valencia)

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 542, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries.