Sacsin

Sacsin also known as DnaJ homolog subfamily C member 29 (DNAJC29) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SACS gene.[2][3] Sacsin is a Hsp70 co-chaperone.[4]

Function

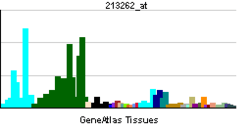

This gene consists of nine exons including a gigantic exon spanning more than 12.8k bp. It encodes the sacsin protein, which includes a UBQ region at the N-terminus, a HEPN domain at the C-terminus and a DnaJ region upstream of the HEPN domain. The gene is highly expressed in the central nervous system, also found in skin, skeletal muscles and at low levels in the pancreas. Mutations in this gene result in autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay (ARSACS), a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by early-onset cerebellar ataxia with spasticity and peripheral neuropathy.[3]

Clinical significance

Autosomal Recessive Spastic Ataxia of the Charlevoix-Saguenay (ARSACS) is a hereditary progressive neurological disorder that primarily affects people from the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean and Charlevoix regions of Quebec or descendants of native settlers in this region. This disorder has also been demonstrated in people from various other countries including India.[5] It is characterized by degeneration of the spinal cord and progressive damage of the peripheral nerves. The disorder is caused by a gene mutation on chromosome 13 (SACS) of the 22 chromosomes that determine characteristics that are not related to sex. This is an autosomal recessive disorder, meaning that both parents must be carriers of the gene in order to have a 25% chance of their child having the disorder at each pregnancy.[6] Mutations of the gene is usually a deletion or replacement of a nucleotide in the SACS gene. The mutation of the SACS gene causes the production of an unstable, poorly functioning SACSIN protein. It is unclear as to how this mutation affects the central nervous system (CNS) and skeletal muscles presenting in the signs and symptoms of ARSACS.[7]

ARSACS is usually diagnosed in early childhood, approximately 12–24 months of age when a child begins to take their first steps. It is a lack of coordination and balance during gait that is first noticed. Children with the disorder take frequent falls and appear to have an unsteady (Ataxic) gait. Some of the signs and symptoms include:[8] Stiffness of the legs, appendicular and trunk ataxia, hollow foot and hand deformities, ataxic dysarthria, distal muscle wasting, horizontal gaze nystagmus, and spasticity.[9]

References

Further reading

- Nagase T, Ishikawa K, Suyama M, et al. (1999). "Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XI. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro.". DNA Res. 5 (5): 277–86. doi:10.1093/dnares/5.5.277. PMID 9872452.

- Engert JC, Bérubé P, Mercier J, et al. (2000). "ARSACS, a spastic ataxia common in northeastern Québec, is caused by mutations in a new gene encoding an 11.5-kb ORF.". Nat. Genet. 24 (2): 120–5. doi:10.1038/72769. PMID 10655055.

- Mercier J, Prévost C, Engert JC, et al. (2002). "Rapid detection of the sacsin mutations causing autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay.". Genet. Test. 5 (3): 255–9. doi:10.1089/10906570152742326. PMID 11788093.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, et al. (2003). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences.". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241

. PMID 12477932.

. PMID 12477932.

- Ota T, Suzuki Y, Nishikawa T, et al. (2004). "Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs.". Nat. Genet. 36 (1): 40–5. doi:10.1038/ng1285. PMID 14702039.

- Criscuolo C, Banfi S, Orio M, et al. (2004). "A novel mutation in SACS gene in a family from southern Italy.". Neurology. 62 (1): 100–2. doi:10.1212/wnl.62.1.100. PMID 14718706.

- Grieco GS, Malandrini A, Comanducci G, et al. (2004). "Novel SACS mutations in autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay type.". Neurology. 62 (1): 103–6. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000104491.66816.77. PMID 14718707.

- Ogawa T, Takiyama Y, Sakoe K, et al. (2004). "Identification of a SACS gene missense mutation in ARSACS.". Neurology. 62 (1): 107–9. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000099371.14478.73. PMID 14718708.

- Dunham A, Matthews LH, Burton J, et al. (2004). "The DNA sequence and analysis of human chromosome 13.". Nature. 428 (6982): 522–8. doi:10.1038/nature02379. PMC 2665288

. PMID 15057823.

. PMID 15057823.

- Richter AM; Ozgul RK; Poisson VC; Topaloglu H (2005). "Private SACS mutations in autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay (ARSACS) families from Turkey.". Neurogenetics. 5 (3): 165–70. doi:10.1007/s10048-004-0179-y. PMID 15156359.

- Shimazaki H, Takiyama Y, Sakoe K, et al. (2006). "A phenotype without spasticity in sacsin-related ataxia.". Neurology. 64 (12): 2129–31. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000166031.91514.B3. PMID 15985586.

- Yamamoto Y, Hiraoka K, Araki M, et al. (2006). "Novel compound heterozygous mutations in sacsin-related ataxia.". J. Neurol. Sci. 239 (1): 101–4. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2005.08.005. PMID 16198375.

- Ouyang Y, Takiyama Y, Sakoe K, et al. (2006). "Sacsin-related ataxia (ARSACS): expanding the genotype upstream from the gigantic exon.". Neurology. 66 (7): 1103–4. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000204300.94261.ea. PMID 16606928.

- Takado Y, Hara K, Shimohata T, et al. (2007). "New mutation in the non-gigantic exon of SACS in Japanese siblings.". Mov. Disord. 22 (5): 748–9. doi:10.1002/mds.21365. PMID 17290461.

External links

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.

PDB gallery |

|---|

|

| 1iur: DnaJ domain of human KIAA0730 protein |

|

|

. PMID 19208651.

. PMID 19208651. . PMID 12477932.

. PMID 12477932. . PMID 15057823.

. PMID 15057823.