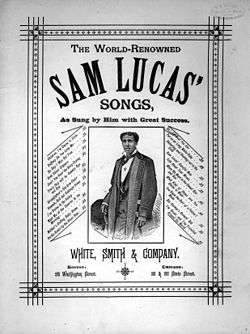

Sam Lucas

Sam Lucas (August 7, 1848 – January 5, 1916)[1][2] was an African American actor, comedian, singer, and songwriter. Sam Lucas's exact date of birth is disputed. Lucas's year of birth, to freed former slaves, has also been cited as 1839, 1840, 1841, and 1850.[3][4][2]

His career began in blackface minstrelsy, but he later became one of the first African Americans to branch out into more serious drama, with roles in seminal works such as The Creole Show and A Trip to Coontown. He was the first black man to portray the role of Uncle Tom on both stage and screen. James Weldon Johnson described him as the "Grand Old Man of the Negro Stage".[5]

Early career

Lucas was born Samuel Mildmay Lucas (or Samuel Lucas Milady)[6] in Washington Court House, Ohio to free black parents. He showed a talent for guitar and singing as a teenager, and while working as a barber, his local performances gained him a positive reputation.

In 1858 he began his career as a performer with the traveling African-American minstrel companies. Over the next five years, he sang and acted on stage and on riverboats, and composed music for his shows. Meanwhile, he found ways to integrate his African-American roots into the mostly white form; for instance, his tune "Carve Dat Possum" borrowed its melody from a black religious song. As black minstrelsy grew popular with the general public, Lucas became one of its first celebrities, particularly known for his portrayals of pitiable, comic characters.

His fame allowed him to choose his engagements, and over the span of his career, he performed with some of the best black minstrel troupes. He never led a troupe of his own, however. Throughout his life, Lucas performed with many minstrel groups including Lew Johnson's Plantation Minstrels (1871–73), Callender’s Georgia Minstrels (1873–74, 1875–76), and Sprague’s Georgia Minstrels (1878–79) in Havana, Cuba.[3] After his time as a minstrel performer, Lucas began to perform in vaudeville.

Dramatic roles

Meanwhile, Lucas attempted to branch out into non-minstrel material. In 1875, for instance, he performed alongside Emma and Anna Hyer in Out of Bondage, a musical drama about a freed slave who is made over to fit into upper-class, white society. He followed this by another stint in black minstrelsy, and in 1876, he was playing with Sprague's Georgia Minstrels, alongside both James A. Bland and Billy Kersands.

In 1878, Charles and Gustave Frohman needed an advertising gimmick to help rescue a poorly performing comedy troupe. Their answer was to stage a serious production of Uncle Tom's Cabin with a black man in the lead role. Lucas's reputation as an actor was well known, as was his wealth; Gustave wired Charles, "Get me an Eva and send her down with Sam Lucas. Be sure to tell Sam to bring his diamonds."[7]

Lucas became the first African American to play Uncle Tom in a serious production. Nevertheless, the show fared poorly in Richmond, Virginia, and not even a change of venue to Lucas's home state of Ohio could save the production. The problems seem to have been many. One critic remarked that "little" Eva was so large that she nearly flattened St. Clair when she sat in his lap. Lucas had to hawk his stash of diamonds to pay the troupe's transport back to Cincinnati.

Lucas rejoined the Hyer sisters for The Underground Railroad, only to go back to blackface acts after its run. He also continued to write, and much of his output shows a more African American perspective when compared to work of other black composers, such as James Bland.[8] For example, the lyrics to "My Dear Old Southern Home" say:

- I remember now my poor wife's face,

- Her cries ring in my ear;

- When they tore me from her wild embrace,

- And sold me way out yere.

- My children sobbed about my knees,

- They've all grown up since then,

- But bress de Lord de good time's come;

- I'se freed by dose Northern men.[9]

Another Lucas tune declares, "I nebber shall forget, no nebber, / De day I was sot free."[10]

Later career

In 1890, Lucas served as an endman in Sam T. Jack's The Creole Show, often cited as the first African American production to show signs of breaking the links to minstrelsy.[11]

He married during its run, and afterward he and his wife played a succession of variety houses, vaudeville stages, and museums. In 1898, he performed in Boston in A Trip to Coontown, produced by Bob Cole. This was the first black production to use only African American writers, directors, and producers,[11] and the first black musical comedy to make a complete break with minstrelsy.[12]

From 1905-06, he starred in Rufus Rastus, which was directed by Ernest Hogan. In 1097, Lucas starred in the second showing of an original musical comedy from Cole and Johnson, The Shoe-Fly Regiment, which ran from June 3, 1907 to August 17, 1907. This production showed at the Grand Opera House in New York City from June 6–8, 1907 and at the Bijou Theatre, which was also located in New York, from August 6 to August 17, 1907. The Shoe-Fly Regiment was a three-act musical, with Acts One and Three taking place in the Lincolnville Institute in Alabama and act two taking place in the Philippines. Lucas played Brother Doolittle, who was a member of the Bode of Education.[13]

Lucas later performed in another original musical comedy The Red Moon, portraying Bill Webster, a barber. The Red Moon ran from May 3, 1909 to May 29, 1909. The Red Moon was also a three-act musical, but set in fictional "Swamptown, Virginia".[14]

In 1908, he became a charter member for the professional theatrical club The Frogs, and in 1913 he participated in The Frog Follies.[15]

Lime Kiln Field Day (1913)

In 1913, Lucas was featured in the unfinished film, Lime Kiln Field Day, produced by the Biograph Company and Klaw and Erlanger. The footage of the unfinished film was assembled in 2014 by the Museum of Modern Art, which had rescued the film cans from a Biograph film storage vault in 1938.

Uncle Tom's Cabin (1914)

In 1914, Lucas revived his role of Uncle Tom in William Robert Daly's film adaptation of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom’s Cabin. He is generally credited as the first black man to portray Uncle Tom, who had typically been played by white actors in black face. The film was released on August 10, 1914 by the World Film Company.[16]

The film was shot on location in the South; authentic fields of cotton and Mississippi river boats are shown in the film. This was a silent film, which was accompanied by organs or other instruments at local theatres. In 2012, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was selected as one of 25 to be entered in the National Film Registry in the Library of Congress.

Personal life

Lucas was married no fewer than three times; his second wife was Carrie Melvin, whom he married in Boston, Massachusetts on August 11, 1886.[1]

Carrie Melvin Lucas was a violinist, coronetist, and actress. They had one daughter together, Marie Lucas (1891–1947). Marie went on to become a successful pianist, trombonist, arranger, and conductor. Sam and Carrie performed together in vaudeville, but they divorced in 1899. Marie and Sam later worked together.

Death

After completing Uncle Tom's Cabin, Lucas, believed to be 67 years old, died in 1916 from pneumonia, after suffering from liver disease for many years.

See also

Bibliography

- Graham, Sandra Jean (2013). "The Songs of Sam Lucas", Center for Popular Music, Middle Tennessee State University.

- Toll, Robert C. (1974). Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-century America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Watkins, Mel (1994). On the Real Side: Laughing, Lying, and Signifying—The Underground Tradition of African-American Humor that Transformed American Culture, from Slavery to Richard Pryor. New York: Simon & Schuster.

References

- 1 2 "Massachusetts, Marriages, 1695-1910" index, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FH6M-25N; accessed May 15, 2015), Samuel Lucas and Caroline Melvin, August 11, 1886; citing reference; FHL microfilm 823,138.

- 1 2 "Profile of Sam Lucas". IMDb.com. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- 1 2 Peterson, Bernard L (2001). Profiles of African American Stage Performers and Theatre People, 1816-1960. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 170.

- ↑ Southern, Eileen (1997). The Music of Black Americans: A History. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 240.

- ↑ Johnson (1968). Black Manhattan, p. 90. Quoted in Toll 218.

- ↑ Nicholls, David (1998). The Cambridge history of American music (1st publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521454292. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ↑ Toll, pp. 217-218.

- ↑ Watkins, p. 119.

- ↑ Quoted in Toll 247. Toll does not specify whether this piece was published in Sam Lucas' Plantation Songster, c. 1875, or in Sam Lucas' Careful Man Songster, c. 1881.

- ↑ Lucas, Sam (1878). Sheet music, "De Day I Was Sot Free". Quoted in Toll 247.

- 1 2 Watkins, p. 118.

- ↑ Toll, p. 218.

- ↑ "Bode of Education details". Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ↑ "The Red Moon details". Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ↑ Peterson, Bernard L (2001). Profiles of African American Stage Performers and Theatre People, 1816-1960. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 171.

- ↑ "Uncle Tom's Cabin details". Retrieved December 9, 2014.