Scribe

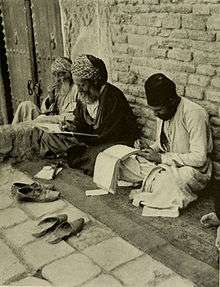

A scribe is a person who writes books or documents by hand in hieratics, cuneiform or other scripts and may help keep track of records for priests and government.

Description

The profession, previously found in all literate cultures in some form, lost most of its importance and status with the advent of printing. The work could involve copying books, including sacred texts, or secretarial and administrative duties, such as taking of dictation and the keeping of business, judicial and, historical records for kings, nobles, temples, and cities. Later the profession developed into public servants, journalists, accountants, typists, and lawyers. In societies with low literacy rates, street-corner letter-writers (and readers) may still be found providing a service.

Ancient Egypt

The most important was a person educated in the arts of writing (using both hieroglyphics and hieratic scripts, and from the second half of the first millennium BCE the demotic script, used as shorthand and for commerce) and arithmetics.[1][2] Sons of scribes were brought up in the same scribal tradition, sent to school and, upon entering the civil service, inherited their fathers' positions.[3]

Much of what is known about ancient Egypt is due to the activities of its scribes and the officials. Monumental buildings were erected under their supervision,[4] administrative and economic activities were documented by them, and tales from the mouths of Egypt's lower classes or from foreign lands survive thanks to scribes putting them in writing.[5]

Scribes were also considered part of the royal court, were not conscripted and did not have to pay taxes. The scribal profession had companion professions, the painters and artisans who decorated reliefs and other relics with scenes, personages, or hieroglyphic text. A scribe was exempt from the heavy manual labor required of the lower classes, or corvee labor.

|

|

Thoth was a god associated by the Ancient Egyptians with the invention of writing, being the scribe of the gods, and holding knowledge of scientific and moral laws.[6]

Egyptian and Mesopotamian functions

Besides the scribal profession for accountancy, and 'governmental politicking' , the scribal professions immediately branched-out into the socio-cultural areas of literature. The first stories probably related to societal religious stories, and gods, but the beginning of literature genres were starting.

In ancient Egypt an example of this is the Dispute between a man and his Ba. Some of these stories, the "wisdom literatures" may have just started as a 'short story', but since writing had only recently been invented, it was the first physical recordings of societal ideas, in some length and detail. In Mesopotamia, the Sumerians had one of the beginnings of this literature in the middle to late 3rd millennium BC, and besides their creation stories, and religious texts, there is a series of debates. An example from the small list of Sumerian disputations is the debate between bird and fish.[7] In the other Sumerian disputes, in the debate between Summer and Winter, Winter wins. The other disputes are: cattle and grain, the tree and the reed, Silver and Copper, the pickax and the plough, and millstone and the gul-gul stone.[8]

Judaism

Scribes in Ancient Israel, as in most of the ancient world, were distinguished professionals who could exercise functions we would associate with lawyers, government ministers, judges, or even financiers, as early as the 11th century BCE.[9] Some scribes copied documents, but this was not necessarily part of their job.[10]

The Jewish scribes used the following process for creating copies of the Torah and eventually other books in the Tanakh.

- They could only use clean animal skins, both to write on, and even to bind manuscripts.

- Each column of writing could have no less than forty-eight, and no more than sixty lines.

- The ink must be black, and of a special recipe.

- They must say each word aloud while they were writing.

- They must wipe the pen and wash their entire bodies before writing the most Holy Name of God, YHVH, every time they wrote it.

- There must be a review within thirty days, and if as many as three pages required corrections, the entire manuscript had to be redone.

- The letters, words, and paragraphs had to be counted, and the document became invalid if two letters touched each other. The middle paragraph, word and letter must correspond to those of the original document.

- The documents could be stored only in sacred places (synagogues, etc.).

- As no document containing God's Word could be destroyed, they were stored, or buried, in a genizah.

Sofer

Sofers (Hebrew: סופר סת”ם) are among the few scribes that still ply their trade by hand. Renowned calligraphers, they produce the Hebrew Torah scrolls and other holy texts by hand to this day. They write on parchment.

Sofer accuracy

Until 1948, the oldest manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible dated back to 895 A.D. In 1947, a shepherd boy discovered some scrolls inside a cave West of the Dead Sea. These manuscripts dated between 100 B.C. and 100 A.D. Over the next decade, more scrolls were found in caves and the discovery became known as the Dead Sea Scrolls. Every book in the Hebrew Bible was represented in this discovery except Esther. Numerous copies of each book were discovered, such as the 25 copies of Deuteronomy that were found.

While there are other items found among the Dead Sea Scrolls not currently in the Hebrew Bible, the texts on the whole testify to the accuracy of the scribes copying down through the ages, though many variations and errors occurred.[11] The Dead Sea Scrolls are currently the best route of comparison to the accuracy and consistency of translation for the Hebrew Bible, due to their date of origin being the oldest out of any Biblical text currently known.

See also

- Copying

- List of ancient Egyptian scribes

- Scrivener

- Scriptorium

- The Seated Scribe

- Transcription (linguistics)

- Transliteration

- Uncial

- Worshipful Company of Scriveners

- Scribes and Scribal Education in Ancient Egypt

Notable scribes

- Ahmes

- Amat-Mamu

- Baruch

- Dubhaltach MacFhirbhisigh

- Máel Muire mac Céilechair

- Sidney Rigdon

- Sin-liqe-unninni

Notes

- ↑ Michael Rice, Who's Who in Ancient Egypt, Routledge 2001, ISBN 0-415-15448-0, p.lvi

- ↑ Peter Damerow, Abstraction and Representation: Essays on the Cultural Evolution of Thinking, Springer 1996, ISBN 0-7923-3816-2, pp.188ff.

- ↑ David McLain Carr, Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature, Oxford University Press 2005, ISBN 0-19-517297-3, p.66

- ↑ Kemp, op.cit., p.180

- ↑ Kemp, op.cit., p.296

- ↑ Budge, E. A. Wallis. The Gods of the Egyptians. New York: Dover Publications, 1969 (original in 1904).

- ↑ ETSCL translation: The Debate between Bird and Fish

- ↑ ETSCL, "Debate poems"

- ↑ http://www.omniglot.com/writing/hebrew.htm

- ↑ Bruce Metzger and Michael Coogan, eds., The Oxford Companion to the Bible.

- ↑ "A History of the Jews", Paul Johnson, p. 91, Phoenix, 1993 (org pub 1987), ISBN 1-85799-096-X

References

- Barry J. Kemp, Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization, Routledge 2006, ISBN 0-415-23549-9, pp. 166ff.

- Henri-Jean Martin, The History and Power of Writing, University of Chicago Press 1995, ISBN 0-226-50836-6

- David McLain Carr, Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature, Oxford University Press 2005, ISBN 0-19-517297-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scribes. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scribes of Ancient Egypt. |

- Some Old Egyptian Librarians, Ernest Gushing Richardson, Charles Sribners, 1911

- Catholic Encyclopedia

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "article name needed". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "article name needed". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.