Siege of Nice

| Siege of Nice | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman-Habsburg Wars | |||||||

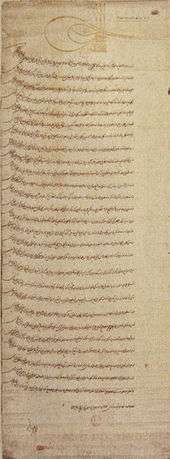

Top: In the Siege of Nice in 1543, a combined Franco-Ottoman force captured the city. Bottom: Ottoman depiction of the siege of Nice by Matrakçı Nasuh. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5,000 captives. | |||||||

The Siege of Nice occurred in 1543 and was part of the Italian War of 1542–46 in which Francis I and Suleiman the Magnificent collaborated in a Franco-Ottoman alliance against the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, and Henry VIII of England. At that time, Nice was under the control of Charles III, Duke of Savoy, an ally of Charles V.[2] This is part of the 1543–1544 Mediterranean campaign of Barbarossa.[3]

Siege

In the Mediterranean, active naval collaboration took place between France and the Ottoman Empire to fight against Spanish forces, following a request by Francis I, conveyed by Antoine Escalin des Aimars. The French forces, led by François de Bourbon, and the Ottoman forces, led by Hayreddin Barbarossa, first joined at Marseilles in August 1543.[4] Although the Duchy of Savoy, of which Nice was a part, had been a French protectorate for a century, Francis I chose to attack the city of Nice with the allied force, mainly because Charles III, Duke of Savoy had angered him by marrying Beatrice of Portugal, thus becoming an ally of the Habsburgs.[5]

François de Bourbon had already attempted to make a surprise attack on Nice once, but had been repulsed by Andrea Doria.[6]

Arrival of the Ottoman fleet

Following an agreement between Francis I and Suleyman the Magnificent, through the intervention of the French ambassador in Constantinople Polin, a fleet of 110 galleys under Hayreddin Barbarossa left from the Sea of Marmara in mid-May 1543.[7] He then raided the coasts of Sicilia and Southern Italy through the month of June, anchoring in front of Rome at the mouth of the Tiber on 29 June, while Polin wrote reinsurances that attacks against Rome would not take place.[7]

Barbarossa arrived with his fleet, accompanied by the French Ambassador Polin, at Île Saint-Honorat on 5 July. As almost nothing had been prepared on the French side to assist the Ottoman fleet, Polin was dispatched to meet with Francis I at Marolles and ask him for support. Meanwhile, Barbarossa went to the harbour of Toulon on 10 July and then was received with honours at the harbour of Marseilles on 21 July, where he joined the French forces under the Governor of Marseille, François, Count of Enghien.[7][8] The combined fleet sailed out of Marseille on the 5th of August.[9]

Siege

The Ottoman force first landed at Villefranche, 6 kilometers east of Nice, which it took and destroyed.[10]

The French and Ottoman forces then collaborated to attack the city of Nice on 6 August 1543.[11][12] In this action 110 Ottoman galleys combined with 50 French ones.[13]

The Franco-Ottomans were confronted by a stiff resistance which gave rise to the story of Catherine Ségurane, culminating with a major battle on 15 August, but the city surrendered on 22 August. The French prevented the Ottomans from sacking the city.[14] They could not however take the castle, the "Château de Cimiez", apparently because the French were unable to supply sufficient gunpowder to their Ottoman allies.[14][15][16]

Another important battle against the castle took place on 8 September, but the force finally retreated upon learning that an Imperial army was on the move to meet them: Duke Charles III, ruler of the Duchy of Savoy, had raised an army in Piedmont to free the city.[17]

The last night before leaving, Barbarossa plundered the city, burned parts of it, and took 5,000 captives.[18] The relief army, transported on ships by Andrea Doria, landed at Villefranche, and successfully made its way to the Nice citadel.[7]

During the campaign, Barbarossa is known to have complained about the state of the French ships and the inappropriateness of their equipment and stores.[15] He famously said "Are you seamen to fill your casks with wine rather than powder?".[19] He nevertheless displayed great reluctance to attack Andrea Doria when the latter was put in difficulty after landing the relief army, losing 4 galleys in a storm.[7] It has been suggested that there was some tacit agreement between Barbarossa and Doria on this occasion.[7]

French royal artillery (white flags, left) besieging Nice.

French royal artillery (white flags, left) besieging Nice. Ottoman landing in Villefranche.

Ottoman landing in Villefranche. Main landing at Nice.

Main landing at Nice.

Catherine Ségurane

Catherine Ségurane (Catarina Ségurana in the Niçard dialect of Provençal) is a folk heroine of the city of Nice, France who is said to have played a decisive role in repelling the city's siege by Turkish invaders allied with Francis I, the Siege of Nice, in the summer of 1543. At the time, Nice was part of Savoy, independent from France, and had no standing military to defend it. Most versions of the tale have Catherine Ségurane, a common washerwoman, leading the townspeople into battle. Legend has it that she knocked out a standard bearer with her beater and took his flag.

However, according to one commonly told story, Catherine took the lead in defending the city by standing before the invading forces and exposing her bare bottom. This is said to have so repulsed the Turkish infantry's Muslim sense of decency that they turned and fled. However, in Turkish culture, the practice of "mooning" is considered odd or absurdly immoral but never offensive and most probably as a sexual teasing, especially when performed by a female.

Catherine's existence has never been definitively proven, and her heroic act of mooning is likely pure fiction or highly exaggerated; Jean Badat, a historian who stood witness to the siege, made no mention of her involvement in the defense. Historically attested defense of Nice include the townspeople's destruction of a key bridge and the arrival of an army mustered by a Savoyard duke, Charles III. Nevertheless, the legend of Catherine Ségurane has excited the local imagination. Louis Andrioli wrote an epic poem about her in 1808, and a play dedicated to her story was written by Jean-Baptiste Toselli in 1878. In 1923, a bas-relief monument to Catherine was erected near the supposed location of her feat. In Nice, Catherine Segurane Day is celebrated annually, concurrent with St. Catherine's Day on 25 November.

Ottoman wintering in Toulon

Following the siege, the Ottomans were offered by Francis to winter at Toulon, so that they could continue to harass the Holy Roman Empire, and especially the coast of Spain and Italy, as well the communications between the two countries. Barbarossa was also promised that he would receive help from the French in reconquering Tunis if he stayed through the winter in France.[7]

Throughout the winter, the Ottoman fleet, with its 110 galleys and 30,000 troops, was able to use Toulon as a base to attack the Spanish and Italian coasts under Admiral Salih Reis.[7][20] They raided Barcelona in Spain, and Sanremo, Borghetto Santo Spirito, Ceriale in Italy, and defeated Italo-Spanish naval attacks.[21] Sailing with his whole fleet to Genoa, Barbarossa negotiated with Andrea Doria the release of Turgut Reis.[22] France provided about 10,000,000 kilograms of bread to supply the Ottoman army during the 6 months it stayed in Toulon, and for the provisioning of the following summer's campaign and return to Constantinople.[7]

It seems the involvement of Francis I to this joint effort with the Ottomans were rather half-hearted however, as many European powers were complaining about such an alliance against another Christian power.[23] Relations remained tensed and suspicious between the two allies.[15]

Aftermath

A French-Habsburg peace treaty was finally signed at Crépy on 18 September 1544, and a truce was signed between the Habsburg and the Ottomans on 10 November 1545.[15] The Habsburg emperor Charles V agreed to recognize the new Ottoman conquests. A formal peace treaty was signed on 13 June 1547, after the death of Francis I.[15]

A local consequence of the siege was the reinforcement of the coast with defensive fortifications, especially the castles of Nice and Mont Alban, and the fort of Saint-Elme de Villefranche.

See also

Notes

- ↑ John Brian Harley (2000-11-23). Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies. Books.google.com. p. 245. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ Suraiya Faroqhi. The Ottoman Empire and the World Around It. Books.google.com. p. 33. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑

- ↑ Hugh James Rose. A New General Biographical Dictionary. Books.google.com. p. 138. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- 1 2 McCabe, p.42

- ↑ Robert J. Knecht (2002-01-21). The Rise and Fall of Renaissance France: 1483-1610. Books.google.com. p. 181. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Barbarossa arrived at Toulon on 10 July, and (as the Venetian Senate wrote Suleiman) was received with honor in Marseille on the twenty first. In August he assisted the French in the badly-planned and unsuccessful siege of Nice" in The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571 by Kenneth Meyer Setton p.470ff

- ↑ Contemporaries of Erasmus: A Biographical Register of the Renaissance and ... Books.google.com. p. 260. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Books.google.com. p. 428. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936. Books.google.com. p. 873. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ Suraiya Faroqhi (2005-11-29). Subjects of the Sultan: Culture and Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire. Books.google.com. p. 70. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ Daniel Goffman (2002-04-25). The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe. Books.google.com. p. 21. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of Islam, p.328

- 1 2 Robert Elgood (1995-11-15). Firearms of the Islamic World: In the Tared Rajab Museum, Kuwait. Books.google.com. p. 38. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sir Edward Shepherd Creasy. History of the Ottoman Turks: From the Beginning of Their Empire to the ... Books.google.com. p. 286. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ McCabe, p.41

- ↑ McCabe, p.43

- ↑ Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Books.google.com. p. 428. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ Harold Lamb. Suleiman the Magnificent - Sultan of the East. Books.google.com. p. 229. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ Harold Lamb. Suleiman the Magnificent - Sultan of the East. Books.google.com. p. 230. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ Robert Elgood (1995-11-15). Firearms of the Islamic World: In the Tared Rajab Museum, Kuwait. Books.google.com. p. 38. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑

- ↑

References

- William Miller The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801–1927 Routledge, 1966 ISBN 0-7146-1974-4

- Peter Malcolm Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis The Cambridge History of Islam Cambridge University Press, 1977 ISBN 0-521-29135-6

- Roger Crowley, Empire of the sea, 2008 Faber & Faber ISBN 978-0-571-23231-4

- Baghdiantz McAbe, Ina 2008 Orientalism in Early Modern France, ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0, Berg Publishing, Oxford

External links

Coordinates: 43°42′00″N 7°16′00″E / 43.7°N 7.26667°E