Harold Nicolson

| Sir Harold Nicolson KCVO CMG | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of Parliament for Leicester West | |

|

In office 14 November 1935 – 5 July 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Ernest Harold Pickering |

| Succeeded by | Barnett Janner |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Harold George Nicolson 21 November 1886 Tehran, Persian Empire |

| Died |

1 May 1968 (aged 81) Sissinghurst Castle, Kent |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | National Labour and Labour Party |

| Spouse(s) | Vita Sackville-West |

| Children | Nigel Nicolson, Benedict Nicolson |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford |

| Occupation | British diplomat, author, diarist and politician |

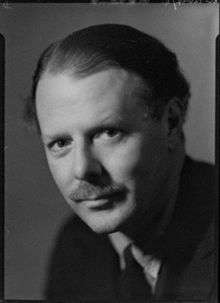

Sir Harold George Nicolson KCVO CMG (21 November 1886 – 1 May 1968) was a British diplomat, author, diarist and politician.

He was the husband of writer Vita Sackville-West.

Early life

Nicolson was born in Tehran, Persia, the youngest son of diplomat Arthur Nicolson, 1st Baron Carnock. He was educated at Wellington College and Balliol College, Oxford.

Diplomatic career

In 1909 Nicolson joined HM Diplomatic Service. He served as attaché at Madrid from February to September 1911, and then Third Secretary at Constantinople from January 1912 to October 1914. During the First World War, he served at the Foreign Office in London, during which time he was promoted Second Secretary. As the Foreign Office's most junior employee at this rank, it fell to him in August 1914 to hand Britain's revised declaration of war to the German ambassador in London. He served in a junior capacity in the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, for which he was appointed Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in the 1920 New Year Honours.[1]

Promoted First Secretary in 1920, he was appointed private secretary to Sir Eric Drummond, first Secretary-General of the League of Nations, but was recalled to the Foreign Office in June 1920.

In 1925, he was promoted Counsellor and posted to Tehran as Chargé d'affaires. However, in Summer 1927 he was recalled to London and demoted to First Secretary for criticising his Minister, Sir Percy Loraine, in a dispatch. He was posted to Berlin as Chargé d'affaires in 1928. He was promoted Counsellor again, but resigned from the Diplomatic Service in September 1929.

Political career

From 1930 to 1931, Nicolson edited the Londoner's Diary for the Evening Standard, but disliked writing about high-society gossip and quit within a year.

In 1931, he joined Sir Oswald Mosley and his recently formed New Party. He stood unsuccessfully for Parliament for the Combined English Universities in the general election that year and edited the party newspaper, Action. He ceased to support Mosley when the latter formed the British Union of Fascists the following year.

Nicolson entered the House of Commons as National Labour Member of Parliament (MP) for Leicester West in the 1935 election. In the latter half of the 1930s he was among a relatively small number of MPs who alerted the country to the threat of fascism. More a follower of Anthony Eden in this regard than of Winston Churchill, he nevertheless was a friend (though not an intimate) of Churchill, and often supported his efforts in the Commons to stiffen British resolve and support rearmament.

He became Parliamentary Secretary and official Censor [2] at the Ministry of Information in Churchill's 1940 wartime government of national unity, serving under Cabinet member Duff Cooper for approximately a year until he was asked by Churchill to leave his position;[3] thereafter he was a well-respected backbencher, especially on foreign policy issues given his early and prominent diplomatic career. From 1941 to 1946 he was also on the Board of Governors of the BBC. He lost his seat in the 1945 election. A Francophile, when Nicolson visited France in March 1945, for the first time in five years, upon landing in France, he kissed the earth.[4] When a Frenchman asked the prostrate Nicolson "Monsieur a laissé tomber quelque-chose?" ("Sir, have you dropped something?"), Nicolson replied "Non, j'ai retrouvé quelque-chose" (No, I have recovered something").[5] The exchange is little known in Britain, but is well remembered in France.[6] The Having joined the Labour Party, he stood in the Croydon North by-election in 1948, but lost once again.

Writer

Encouraged in his literary ambitions by his wife Vita Sackville-West,[7] also a writer, Nicolson published a biography of French poet Paul Verlaine in 1921, to be followed by studies of other literary figures such as Tennyson, Byron, Swinburne and Sainte-Beuve. In 1933, he wrote an account of the Paris Peace Conference entitled Peacemaking 1919.

Nicolson is also remembered for his 1932 novel Public Faces, foreshadowing the nuclear bomb. A fictional account of British national policy in 1939, it tells how Britain's secretary of state tried to keep world peace, even with the Royal Air Force aggressively brandishing rocket airplanes and an atomic bomb. In today's terms, it was a multi-megaton bomb, and the geology of the Persian Gulf played a central role, but on the other hand, Nicolson never foresaw Hitler.

After Nicolson's last attempt to enter Parliament, he continued with an extensive social schedule and his programme of writing, which included books, book reviews, and a weekly column for The Spectator.

His diary is one of the pre-eminent British diaries of the 20th century and a noteworthy source on British political history from 1930 through the 1950s, particularly in regard to the run-up to World War II and the war itself: Nicolson served in high enough echelons to write of the workings of the circles of power and the day-to-day unfolding of great events. His fellow parliamentarian Robert Bernays characterized Nicolson as being "...a national figure of the second degree." Nicolson was variously an acquaintance, associate, friend, or intimate to such figures as Ramsay MacDonald, David Lloyd George, Alfred Duff Cooper, Charles de Gaulle, Anthony Eden and Winston Churchill, along with a host of literary and artistic figures.

Personal life

In 1913, Nicolson married Vita Sackville-West. Nicolson and his wife practised what today would be called an open marriage. Once, Nicolson had to follow Vita to France, where she had "eloped" with Violet Trefusis, to try to win her back. Nicolson himself was no stranger to homosexual affairs. Among others, he was involved in a long-term relationship with Raymond Mortimer, whom both he and Vita affectionately referred to as "Tray". They discussed their shared homosexual tendencies frankly with each other,[8] and remained happy together. They were famously devoted to each other, writing almost every day when separated due to Nicolson's long diplomatic postings abroad, or Vita's insatiable wanderlust. Eventually, he gave up diplomacy, partly so they could live together in England.

They had two sons, Benedict, an art historian, and Nigel, a politician and writer. His younger son Nigel published works by and about his parents, including Portrait of a Marriage, their correspondence, and Nicolson's diary.

In the 1930s, he and his wife acquired and moved to Sissinghurst Castle, near Cranbrook in Kent, the county known as the garden of England. There they created the renowned gardens that are now run by the National Trust.

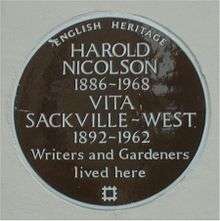

There is a brown "blue plaque" commemorating him and Vita Sackville-West on their house in Ebury Street, London SW1.

Honours

He was appointed Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO) in 1953, as a reward for writing the official biography of George V, which had been published in the previous year.[9]

Works

- Paul Verlaine (1921)

- Sweet Waters (1921) novel; new edition in 2012 by Eland

- Tennyson: Aspects of His Life, Character and Poetry (1923)

- Byron: The Last Journey (1924)

- Swinburne (1926)

- Some People (1927)

- Swinburne and Baudelaire The Zaharoff Lecture (1930)

- Portrait of a Diplomatist (1930)

- People and Things: Wireless Talks (1931)

- Public Faces (1932) novel

- Peacemaking 1919 (1933)

- Curzon: The Last Phase, 1919–1925: A Study in Post-War Diplomacy (1934)

- Dwight Morrow (1935)

- Politics on the Train (1936)

- Helen's Tower (1937)

- Small Talk (1937)

- Diplomacy: a Basic Guide to the Conduct of Contemporary Foreign Affairs (1939)

- Marginal Comment (January 6-August 4, 1939) (1939)

- Why Britain is at War (1939)

- The Desire to Please: The Story of Hamilton Rowan and the United Irishmen (1943)

- The Poetry of Byron: The English Association Presidential Address, August 1943 (1943)

- Friday Mornings 1941–1944 (1944)

- England: An Anthology (1944)

- Another World Than This (1945) anthology, editor with Vita Sackville-West

- The Congress of Vienna: A Study in Allied Unity: 1812–1822 (1946)

- Comments 1944–1948 (1948)[10] – collected articles from the Spectator

- Benjamin Constant (1949)

- King George V (1952)[9]

- The Evolution of Diplomacy (1954) Chichele Lectures 1953

- The English Sense of Humour and other Essays (1946)

- Good Behaviour, being a Study of Certain Types of Civility (London: Constable and Company, 1955)

- Sainte-Beuve (Constable, 1957)

- Journey to Java (London: Constable, 1957)

- The Development of English Biography (London: The Hogarth Press)

- The Age of Reason (1700–1789) (1960)

- Tennyson: Aspects of his Life, Character & Poetry (Arrow, 1960) - 'Grey Arrow Books no.39'

- Monarchy (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1962)

- Diaries and Letters 1930-39; Diaries and Letters 1939-45; Diaries and Letters 1945-62 (1966–68) - edited by Nigel Nicolson

Footnotes

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 31712. p. 5. 30 December 1919.

- ↑ Ahmed Ali. Twilight in Delhi. Bombay: Oxford University Press, 1966, p. 2. This is from the introduction to the book, in which its author tells of H.N.'s role in getting it published in 1940. There is no reference to H.N.'s work in this capacity in his published Diaries, presumably due to the Official Secrets Act.

- ↑ Human Smoke: The Beginnings of World War II, the End of Civilization, Nicholson Baker, 2008

- ↑ Bell, P.H France and Britain, 1940-1994: The Long Separation London: Routledge, 2014 page 66.

- ↑ Bell, P.H France and Britain, 1940-1994: The Long Separation London: Routledge, 2014 page 66.

- ↑ Bell, P.H France and Britain, 1940-1994: The Long Separation London: Routledge, 2014 page 66.

- ↑ Bristow-Smith, Harold Nicolson pp.169-170

- ↑ Bristow-Smith, Harold Nicolson pp.164-165, p.227, pp.249-250

- 1 2 Nicolson, Harold (1952). King George the Fifth, His Life and Reign. London: Constable. ISBN 978-0-09-453181-9. OCLC 1633172. Also under OCLC 255946522. Published in America as Nicolson, Harold (1953). King George the Fifth, His Life and Reign. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. OCLC 1007202. Also under OCLC 476173.

- ↑ London: Constable & Co., 1948.

Further reading

- Nigel Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage, (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1973), ISBN 0-297-76645-7.

- Nigel Nicolson (ed.), The Harold Nicolson Diaries 1907–1963, (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004), ISBN 0-297-84764-3

- James Lees-Milne, Harold Nicolson, A Biography, (Chatto & Windus), 1980, Vol. I (1886–1929), ISBN 0-7011-2520-9; 1981, Vol. II (1930–1968), ISBN 0-7011-2602-7.

- Nigel Nicolson (ed.), Vita and Harold. The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson 1910–1962 (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1992), ISBN 0-297-81182-7.

- David Cannadine: Portrait of More Than a Marriage: Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West Revisited. From Aspects of Aristocracy, pp. 210–42. (Yale University Press, 1994), ISBN 0-300-05981-7.

- Norman Rose, Harold Nicolson (Jonathan Cape, 2005), ISBN 0-224-06218-2.

- Derek Drinkwater, Sir Harold Nicolson & International Relations, ( Oxford University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-19-927385-5.

- Laurence Bristow-Smith, Harold Nicolson: Half-an-Eye on History. Letterworth Press, 2014. ISBN 978-2-9700654-5-6.

See also

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Harold Nicolson |

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Harold Nicolson

- Harold Nicolson at Find a Grave

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ernest Harold Pickering |

Member of Parliament for Leicester West 1935–1945 |

Succeeded by Barnett Janner |