Reed Smoot hearings

The Reed Smoot hearings (Smoot hearings or Smoot Case) were a series of Congressional hearings on whether the United States Senate should seat U.S. Senator Reed Smoot, who was elected by the Utah legislature in 1903.[1] Smoot was an apostle in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), one of the top 15 leaders of the church. The hearings began in 1904 and continued until 1907, when the Senate voted. The vote fell short of a two-thirds majority needed to expel a member so he retained his seat.

The premise of the controversy surrounding Smoot's seating in the Senate was claimed to be about the church's practice of polygamy, which the church claimed to have officially abandoned in 1890; as the hearings revealed, however, the practice continued unofficially well into the 20th century. For example, the President of the LDS Church Joseph F. Smith cohabited with his many wives (all of whom he married before 1890) and fathered eleven children after 1890. New plural marriages did end by 1909, but the practice continued until the polygamists died off. Smoot himself only had one wife.

The attorney who represented those protesting Smoot's admittance to the Senate, Robert W. Tayler, explained in his summation that polygamy was irrelevant and the real danger was Mormon belief in revelation. Although it has been claimed that polygamy was largely responsible for deep animosity between the LDS Church and the United States, in reality, it became a cause celebre to help unite Republicans against Democrats. Earlier, when it was well known that Brigham Young was a polygamist, the U.S. President appointed him twice as territorial governor and the Senate ratified the appointment. Much of the American Protestant establishment viewed the LDS Church with distrust. The establishment was also skeptical of Utah politics, which before gaining statehood in 1896 had at times been a theocracy (theodemocracy) and in the early 20th century was still heavily dominated and influenced by the LDS Church.

Election

Prior to being called as an apostle of the LDS Church, Smoot had run for a Senate position, but withdrew before the election. After becoming an apostle in 1900, he received the approval of church president Joseph F. Smith to run again in 1902 as a Republican. The need for this permission was a result of the LDS Church's "Political Manifesto" issued in October 1895, which instituted a policy which required general authorities of the church to be granted approval from the First Presidency to run for political office.[2] In January 1903, the Utah legislature elected Smoot with 46 votes, compared to his Democratic competitor, who won 16.

Controversy

Within days of his election, controversy brewed as Smoot was charged with being "one of a self-perpetuating body of fifteen men who, constituting the ruling authorities of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or 'Mormon' Church, claim, and by their followers are accorded the right to claim, supreme authority, divinely sanctioned, to shape the belief and control the conduct of those under them in all matters whatsoever, civil and religious, temporal and spiritual."[3]

When Senator Smoot arrived in Washington, D.C., in late February 1903, he was met with protests and charges that he was a polygamist, charges he could easily disprove. Unlike B. H. Roberts, who upon election to the House of Representatives was not allowed to sit while hearings took place, Smoot was allowed to be seated. Among the public, old charges of Danites, the Mountain Meadows massacre, and Brigham Young's plural wives were discussed.

In January 1904, Senator Smoot prepared a rebuttal to these criticisms with the help of several non-Mormon lawyers. The actual hearings began in March. LDS Church President Joseph F. Smith took the witness stand and was interrogated for three days. Apostles Matthias F. Cowley and John W. Taylor did not show up after being subpoenaed. Apostle Marriner W. Merrill ignored one subpoena and died soon after being subpoenaed a second time.[4] Taylor fled to Canada. Other witnesses included James E. Talmage; Francis M. Lyman, president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles; Andrew Jenson, church historian; B. H. Roberts; and Moses Thatcher, who had been dropped from the Quorum of the Twelve in 1896.

According to historian Kathleen Flake:

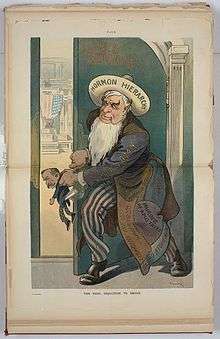

The four-year Senate proceeding created a 3,500-page record of testimony by 100 witnesses on every peculiarity of Mormonism, especially its polygamous family structure, ritual worship practices, "secret oaths," open canon, economic communalism, and theocratic politics. The public participated actively in the proceedings. In the Capitol, spectators lined the halls, waiting for limited seats in the committee room, and filled the galleries to hear floor debates. For those who could not see for themselves, journalists and cartoonists depicted each day's admission and outrage. At the height of the hearing, some senators were receiving a thousand letters a day from angry constituents. What remains of these public petitions fills 11 feet of shelf space, the largest such collection in the National Archives.[5]

After years of hearings, the remaining charges of the opposition included:

- That church leaders were still practicing plural marriage. Apostles John W. Taylor and Matthias F. Cowley were still performing plural marriages in Mexico and Canada, though Taylor was later excommunicated for the practice.

- That the church was exerting too much influence on Utah politics.

- That members were required to take oaths in the temples to seek revenge on the United States. (See: oath of vengeance)

- That members believed revelation was higher than the laws of the land.

The defense included:[6]

- "Reed Smoot possesses all the qualifications prescribed by the Constitution to make him eligible to a seat in the Senate, and the regularity of his election by the legislature of the State of Utah is not questioned in any manner."

- "Aside from his connection with the Mormon Church, so far as his private character is concerned, it is, according to all witnesses, irreproachable, for all who testify on the subject agree or concede that he has led and is leading an upright life".

- "So far as mere belief and membership in the Mormon Church are concerned, he is fully within his rights and privileges under the guaranty of religious freedom given by the Constitution of the United States".

- In relation to the oath, the testimony is "thereby shown to be limited in amount, vague and indefinite in character, and utterly unreliable, because of the disreputable and untrustworthy character of the witnesses."

Of note, Senator Fred Dubois of Idaho fought viciously against Smoot. His intensity caused some to believe that Smoot was as powerful as Dubois claimed. Dubois's ally, Senator Julius C. Burrows of Michigan, made the following statement, speaking of the history of Mormon polygamy:

| “ | In order to induce his followers more readily to accept this infamous doctrine, Brigham Young himself invoked the name of Joseph Smith, the Martyr, whom many sincerely believed to be a true prophet, and ascribed to him the reception of a revelation from the Almighty in 1843, commanding the Saints to take unto themselves a multiplicity of wives, limited in number only by the measures of their desires .... Such the mythical story palmed off on a deluded people.[7] | ” |

One supporter was Senator Boies Penrose of Pennsylvania. Addressing the subject of polygamy, Penrose reportedly glared at one or more of his Senate colleagues who had a reputation for philandering and said, "As for me, I would rather have seated beside me in this chamber a polygamist who doesn't polyg than a monogamist who doesn't monag."[8]

On February 20, 1907, the issue came to a conclusion as a vote was held in the Senate. Smoot won, and he remained a senator for 26 more years.

Aftereffects

| Mormonism and polygamy |

|---|

Portrait of Ira Eldredge with his three wives: Nancy Black Eldredge, Hannah Mariah Savage Eldredge, and Helvig Marie Andersen Eldredge. |

|

Related articles |

|

|

President Joseph F. Smith on April 6, 1904, issued a "Second Manifesto," which reaffirmed the first regarding polygamy. He also declared any church officer who performed a plural marriage, as well as the offending couple, would be excommunicated. He clarified that the policy applied worldwide, not just in North America. Two members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, John W. Taylor and Matthias F. Cowley, resigned in October 1905 following the manifesto. This change to the Twelve was made public in April 1906, when George F. Richards, Orson F. Whitney, and David O. McKay were added to the quorum.

See also

- Utah War (1857–58)

- Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act (1862)

- Poland Act (1874)

- Reynolds v. United States (1879)

- Edmunds Act (1882)

- Edmunds-Tucker Act (1887)

- The Late Corporation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints v. United States (1890)

- 1890 Manifesto

- History of civil marriage in the U.S.

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and politics in the United States

Notes

- ↑ United States Congress (1905). Testimony of Important Witnesses as Given in the Proceedings Before the Reed Smoot Hearings. Salt Lake City: Salt Lake Tribune Publishing Company.

- ↑ Thomas G. Alexander, "Political Manifesto", in Arnold K. Garr, et. al, ed., The Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000) p. 701

- ↑ Ian Shin, "'Scoot – Smoot – Scoot': The Seating Trial of Senator Reed Smoot", Gaines Junction, Spring 2005, archived March 9, 2008 from the original

- ↑ "MORMON APOSTLE DEAD.; Leaves Seven Wives and 49 Children -- Was Wanted as a Witness.". The New York Times. February 8, 1906.

- ↑ "The Politics of American Religious Identity The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle by Kathleen Flake". The University of North Carolina Press.

- ↑ Senate Resolution 205, Fifty-seventh Congress, second session - minority report

- ↑ Congressional Record, December 13, 1906.

- ↑ Beers, Paul B. Pennsylvania Politics Today and Yesterday. University Park and London: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-271-00238-7.

References

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (2003), "The Church in the Early Twentieth Century", Church History in the Fulness of Times: The History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Religion 341–43), Salt Lake City: LDS Church.

- Flake, Kathleen (2004), The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 0-8078-2831-9.

- Heath, Harvard S. (ed.) (1997), In the World: The Diaries of Reed Smoot, Salt Lake City: Signature Books, ISBN 1-56085-051-5.

- Merrill, Milton R. (1950), Reed Smoot, Apostle in Politics (Ph.D. Dissertation), Columbia University.

- Paulos, Michael H (2008), The Mormon Church on trial: transcripts of the Reed Smoot hearings, Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, ISBN 9781560851523, OCLC 173182413.

- Shin, Ian (2005), "Scoot – Smoot – Scoot": The Seating Trial of Senator Reed Smoot" (PDF), Gaines Junction, 3 (1): 143–164.

- Stack, Peggy Fletcher (April 3, 2004), "LDS leader guided church's evolution from 'menace' to mainstream", The Salt Lake Tribune, archived from the original on 2004-06-24.

- United States Senate (1904a), Burrows, Julius Caesar; Foraker, Joseph Benson, eds., Proceedings Before the Committee on Privileges and Elections of the United States Senate in the Matter of the Protests Against the Right of Hon. Reed Smoot, a Senator from the State of Utah, to Hold His Seat, 1, Washington: Government Printing Office.

- United States Senate (1904b), Burrows, Julius Caesar; Foraker, Joseph Benson, eds., Proceedings Before the Committee on Privileges and Elections of the United States Senate in the Matter of the Protests Against the Right of Hon. Reed Smoot, a Senator from the State of Utah, to Hold His Seat, 2, Washington: Government Printing Office.

- United States Senate (1905), Burrows, Julius Caesar; Foraker, Joseph Benson, eds., Proceedings Before the Committee on Privileges and Elections of the United States Senate in the Matter of the Protests Against the Right of Hon. Reed Smoot, a Senator from the State of Utah, to Hold His Seat, 3, Washington: Government Printing Office.

- United States Senate (1906), Burrows, Julius Caesar; Foraker, Joseph Benson, eds., Proceedings Before the Committee on Privileges and Elections of the United States Senate in the Matter of the Protests Against the Right of Hon. Reed Smoot, a Senator from the State of Utah, to Hold His Seat, 4, Washington: Government Printing Office.

- "Testimony of President Joseph F. Smith of the Mormon Church and Senator Reed Smoot." Salt Lake Tribune Publishing Company, 1905.

Further reading

- "The Manifesto and the End of Plural Marriage", lds.org, LDS Church, retrieved 2014-10-22