Souliotes

The Souliotes were an Orthodox Christian community of the area of Souli, in Epirus, known for their military prowess, their resistance to the local Ottoman ruler Ali Pasha, and their contribution to the Greek cause in the Greek War of Independence, under leaders such as Markos Botsaris and Kitsos Tzavelas. The Souliotes established an autonomous confederacy dominating a large number of neighbouring villages in the remote mountainous areas of Epirus, where they could successfully resist Ottoman rule. At the height of its power, in the second half of the 18th century, the community (also called "confederacy") is estimated to have comprised up to 12,000 inhabitants in about 60 villages.[1] The community was classified as Greek[2] in the Ottoman system of social classification because they were Orthodox Christians, yet spoke Albanian besides Greek because of their Albanian origin.[3]

Etymology

The Souliotes (Greek: Σουλιώτες; Albanian: Suljotë[4]) were named after the village of Souli, a mountain settlement in modern Thesprotia, Greece. The name Souli is of uncertain origin.[5] It has been suggested by French historian, François Pouqueville, and other contemporary European accounts that this name derives from the ancient Greek region of Selaida "Σελάϊδα" or "Soulaida" ("Σουλάϊδα") and its inhabitants, the Selloi.[5] Another view by Greek historian, Christoforos Perraivos, who came in personal contact with members of the Souliote community, claimed that it derived from the name of a Turk who was killed there.[5] Pouqueville said that the name was said to have come from xylon, "woody", but noted that it was improbable as there were no trees in the mountains.[6] Yet another view based on etymology claims that the word derives from the Albanian term sul, which can be idiomatically interpreted as 'watchpost', 'lookout' or 'mountain summit'.[5][7] In a study by scholar Petros Fourikis examining the onomastics of Souli, most of the toponyms and micro-toponyms such as: Kiafa, Koungi, Bira, Goura, Mourga, Feriza, Stret(h)eza, Dembes, Vreku i Vetetimese, Sen i Prempte and so on were found to be derived from the Albanian language.[8]

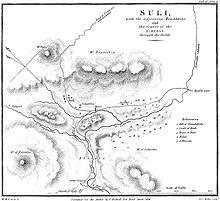

Geography and anthropology

Souli is a community originally settled by refugees who were hunted by the Ottomans in Paramythia, Thesprotia, Greece.[9] Christoforos Perraivos, considered the only one who could have a reliable opinion on the origins of Souliotes because he had personal contacts with them, reports that according to elder Souliotes' narration, the first inhabitants came to Souli in the 16th century from the neighbouring villages, fleeing the Turks.[10] According to Perraivos the first Souliotes were about 450 families. In time, immigrants from elsewhere, attracted by the privileges of autonomy in Souli, assimilated and were also named Souliotes. The Greek peasants who tilled Souliot land were distinguished by the name of the village in which they dwelt. Clan, class and territorial labels had significance in addition to religion.[11]

Around 1730 Souli had not more than 200 men bearing arms. Inhabitants of the neighboring countryside would retire to the mountains to avoid Ottoman oppression and thus the Souliote population increased. Before the final war with Ali Pasha, the families of Souli were:[12]

- Zervaioi, from Zerva, a village near Arta.

- Botzaraioi, originally from Dragani, today Ampelia, south of Paramythia.

- Drakaioi, from Martane, a village of the valley of Lamari, today in Thesprotia prefecture.

- Buzbataioi, from the Vlachochoria (Vlach Villages) of Mt. Pindus.

- Dagliaioi, from Fanari, near Preveza.

- Zavellaioi and Pasataioi, of unknown origin.

In early modern times the total population of Souli was about 12,000[13] After their expulsion, the population of the region was significantly reduced. In the last Greek census of 2001, the population of the community was 748.[14] The seat of the community is in Samoniva. The core of Souli consists of four villages (Greek: Τετραχώρι), namely: Souli (also known as Kakosouli), Avariko (also known as Navariko), Kiafa and Samoniva, which are believed to have been founded some time around 16th century.[9][15]

- Clans

- Antonopoulou (akin to the Botsaris clan; from Vervitsa/Tropaia)[16]

- Kapralaioi (resettled in Messenia)[17]

- Setaioi (resettled in Messenia)

- Douskaioi (resettled in Messenia)

- Dentaioi (resettled in Messenia)

- Zygouraioi (resettled in Kastoria)

- Tzavaraioi (resettled in Messenia and Arcadia)[18]

- Zervaioi[19] (resettled in Boeotia)

Souliotes in the 17th and 18th centuries

17th century

The first settlers are believed to have arrived in the 17th century.[20] By 1660, four large villages had been established: (Kako) Souli, Kiafa, Avariko and Samoniva, collectively called Tetrachorion.[20] These were situated in a plain above the Acheron.[20] The first historical account of anti-Ottoman activity in Souli dates from the Ottoman-Venetian War of 1684–89. In particular in 1685, the Souliotes together with the inhabitants of Himara revolted and overthrew the local Ottoman authorities. This uprising was short lived due to the reaction of the local beys, agas and pashas.[21]

In c. 1700, the population had increased to the extent that seven new villages were formed towards the foot of the mountain, named Tzikouri, Perichati, Vilia, Alpochori, Kondati, Gionala and Tzephleki, collectively called Heptachorion.[20] The latter group constituted the frontier, and when war was rumoured, the men sent their women and children up the mountain to the Tetrachorion.[20]

18th century

In 1731, Hadji Ahmed, pasha of Ioannina, received orders from the Sultan to subdue the Souliotes and he lost his army of 8000 men. In 1754, Mustafa Pasha lost his army to the Souliotes as well. In the following years, Mustafa Koka came in with 4000 soldiers and Bekir Pasha with 5000. In the end, both failed to defeat the Souliotes.

In 1759, Dost Bey, commander of Delvinë, was defeated by the Souliotes, and Mahmoud Aga of Margariti, the governor of Arta, suffered the same fate in 1762. In 1772, Suleyman Tsapari attacked the Souliotes with his army of 9000 men and was defeated. In 1775, Kurt Pasha sent a military expedition to Souli that ultimately failed. When Ali became pasha of Ioannina in 1788, he tried for 15 years to defeat the Souliotes.

During the Russo-Turkish War (1768–74), the inhabitants of Souli, as well as of other communities in Epirus were mobilized for another Greek uprising which became known as Orlov Revolt.[21] In March 1789, the chieftains of Souli: Georgios and Dimitrios Botsaris, Lambros Tzavellas, Nikolaos and Christos Zervas, Lambros Koutsonikas, Christos Photomaras and Demos Drakos, agreed with Louitzis Sotiris, a Greek representative of the Russian side, that they were ready to fight with 2,200 men against the Muslims of Rumelia. This was the time when Ali Pasha became the local Ottoman lord of Ioannina.[21]

In 1792, his army of 3000 was defeated. Although he held hostages (such as Fotos Tzavellas, the son of Lambros Tzavellas), the Souliotes continued the struggle under the command of Georgios Botsaris, Lambros Tzavellas, and Dimos Drakos. Even women under the command of Moscho (Lambros Tzavellas' wife) participated in the battle. Eventually, 2000 Ottomans and 74 Souliotes were killed.

War of 1803 and capitulation

The Souliotes obtained all of their supplies from Parga, and also acquired support from Europe. Russia and France provided weapons and ammunition to them. For the European powers, the Souliotes were seen as an instrument to weaken the Ottoman Empire. When the British politicians turned to the Ottoman Empire in order to strengthen their forces against Napoleon, the weapons and ammunition supplies were interrupted. Without support from outside and wearied by years of siege, the unity of the Souliote clans started to split.

The Botsaris family for political reasons left Souli and parleyed with Ali Pasha. However, the rest in Souli gathered together in Saint George's Orthodox Church and decided either to fight or die. The remaining Souliotes numbered at no more than 2000 armed men. The main leaders were Fotos Tzavellas, Dimos Drakos, Tousas Zervas, Koutsonikas, Gogkas Daglis, Giannakis Sehos, Fotomaras, Tzavaras, Veikos, Panou, Zigouris Diamadis, and Georgios Bousbos. They won all of the decisive battles, which forced Ali Pasha to build castles in neighboring villages so as to prepare himself for a long siege.

Although without food and ammunition, they could have held longer if not for a traitor named Pelios Gousis who helped the Ottomans to enter into the village of Souli, forcing a mass withdraw to the fortresses of Kiafa and Kougi, where they fought their last battle on December 7, 1803. They eventually capitulated and Ali Pasha promised to release them with all of their property and even weapons to the Ionian Islands. On December 12, 1803, the Souliotes left Souli towards the coast of Epirus. A monk named Samuel remained in Kughi and set fire to the powder magazines with a massive explosion that cost him his life. In the meantime, the Ottoman army attacked the other Souliotes, neglecting the promises Ali Pasha had made to them. In a famous incident on December 16, 1803, the so-called Dance of Zalongo, 22 Souliot women were trapped by enemy troops and committed suicide to avoid capture. According to tradition they did this by jumping off a steep cliff one after the other while dancing and singing.

Other Souliotes also reached the harbor of Parga, which was under Russian control at the time. They either settled down in Parga or set off for the Ionian Islands.

Life in exile

Many Souliotes entered service with the Russians on Corfu, where they became an important component of the Legion of Light Riflemen. This was a regiment of irregulars organized by the Russians among mainland refugees; it not only included Souliotes, but also Himariotes, Maniots, klephts (Greek bandits) and armatoloi (Greek anti-klepht militias created by the Ottomans that actually supported the klephts). The formation of this unit was undertaken by the Russian colonel Papadopoulos (Greek in ethnicity). The regiment, initially named "Papadopoulos' Legion", later developed to a formidable army. Its organization was laid down by Papadopoulos in a leaflet in Greek titled "Explanations on the establishment of a legion of Epiro-Souliotes and Himaro-Peloponnesians in the service of His Imperial Majesty Alexander I ...". He recognized that Souliotes and the others were already naturally trained in irregular tactics and did not have to conform to the Western regular tactics. This unit was eventually named "Legion of the Light Riflemen".[23][24] The Souliotes participated in campaigns in Naples in 1805, Tenedos in 1806, Dalmatia in 1806, and during the defense of Lefkada in 1807.[25]

With the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807 and the détente between Russia and France, the Russian forces withdrew from the Ionian Islands and the French occupied them. The Souliotes and other components of Russian units entered service with the French in various units, such as the Battaglione dei Cacciatori Macedoni[26] and the Régiment Albanais (Albanian Regiment), terms which did not have their later ethnic connotation, but were instead stylized terms that described the soldiers' general origins or mode of fighting.[26][27]

Colonel Minot, the commander of the regiment appointed as battalion captains mostly the leaders of Souliote clans who enjoyed the respect among the soldiers. Among them were: Tussa Zervas, George Dracos, Giotis Danglis, Panos Succos, Nastullis Panomaras, Kitsos Palaskas, Kitsos Paschos. Fotos Tzavellas (had served under the Russians), Veicos Zervas.[28]

During the Anglo-French struggle over the Ionian Islands between 1810 and 1814, the Souliotes in French service faced off against other refugees organized by the British into the Greek Light Infantry Regiment. Since the Souliotes were mostly garrisoned on Corfu, which remained under French control until 1814, very few entered British service.[25] The British disbanded the remnants of the Souliot Regiment in 1815 and subsequently decommissioned their own two Greek Light Regiments. This left many of the Souliotes and other military refugees without livelihoods. In 1817, a group of veterans of Russian service on the Ionian Islands traveled to Russia to see if they could get patents of commission and employment in the Russian army. While unsuccessful in this endeavor, they joined the Philike Etaireia ("Company of Friends"), the secret society founded in Odessa in 1814 for the purpose of liberating Greek lands from Ottoman rule. They returned to the Ionian Islands and elsewhere and began to recruit fellow veterans into the Philike Etaireia, including a number of Souliot leaders.[25]

In general the training experience of this period, as part of a regular army, would also serve its cause in the Greek revolution, where Souliotes along with the other warlike groups would form the movement's military core. In 1819, Ioannis Kapodistrias, foreign minister of Russia and latter Governor of Greece visited Corfu. There he was concerned about the potential role the various exiled warlike communities, among them the Souliotes, could play in the forthcoming armed struggle for the liberation of Greece. Latter in 1820, when the Ottoman Sultan declared war against Ali Pasha both sides requested the military assistance of these exiled communities. Thus, Kapodistrias encouraged the latter to take advantage of this opportunity in order to liberate their homelands.[29]

Participation in the Greek War of Independence

The Souliotes were among the first communities like the rest of the other Greek exiles in the Ionian island, encouraged by Kapodistrias that revolted against the Sultan in December 7 [O.S. December 19] 1820. They had already secured at December 4, a short-term alliance with Ali Pasha, and were aware of the objectives of the Philike Etaireia, but their struggle had initially a local character.[30] The negotiations of the Souliotes with Ali Pasha and other Muslim Albanians had the full approval of Alexandros Ypsilantis, leader of the Philike Etaireia, as part of the preparations for the Greek revolution.[31] In this alliance the Souliotes contributed 3,000 soldiers. Ali Pasha gained the support of Souliotes mainly because he offered to allow the return of the Souliotes in their land and partially because of Ali's appeal based on shared Albanian origin.[32] Οn December 12, the Souliotes liberated the region of Souli, both from Muslim Lab Albanians, who were previously installed by Ali Pasha as settlers, and Muslim Cham Albanians who meanwhile defected and fought with the Ottoman side of Pasho bey. They also captured the Kiafa fort.[33]

The uprising of the Souliotes, inspired the revolutionary spirit among the other Greek communities.[34] Soon they were joined by additional Greek communities (armatoles and klepths). Later, in January 1821, even the Muslim Albanian allies of Ali Pasha signed an alliance with them.[35] The successful activity of the various Greek guerilla units in Epirus that time, as well as their alliance with Ali Pasha constituted a great advantage for the objectives of the Filiki Eteria.[36] Τhe coalition with Ali Pasha was successful and controlled most of the region, but when his loyal Muslim Albanian troops were informed of the beginning of the Greek revolts in the Peloponnese they abandoned it and joined the Ottomans.[37] However, when the Greek War of Independence broke out this coalition was terminated and they participated in several conflicts. On the other hand, Ali Pasha's plans failed and he was killed in 1822.[37] In September 1822, HMS Chanticleer was dispatched to Fanari, Preveza, to supervise evacuation of the Souliotes after their capitulation.

The Souliote leaders Markos Botsaris and Kitsos Tzavellas became distinguished generals of the Independence War. However, several Souliotes lost their lives, especially when defending the city of Missolongi. Lord Byron, the most prominent European philhellene volunteer and commander-in-chief of the Greek army in Western Greece, tried to integrate the Souliotes into a regular army. Scores of Souliotes were attached to Lord Byron in 1824, attracted by the money that he was known to bring with him.[38]

Aftermath and legacy

In 1854, during the Crimean War, a number of Greek military officers of Souliote descent, under Kitsos Tzavelas, participated in a failed revolt in Epirus, demanding union with Greece.[40] Until 1909, the Ottomans kept a military base on the fortress of Kiafa. Finally in 1913, during the Balkan Wars, the Ottomans lost Epirus and the southern part of the region became part of the Greek state.

Members of the Souliote diaspora that lived in Greece played a major role in 19th- and 20th-century politics and military affairs, like Dimitrios Botsaris, the son of Markos Botsaris,[41] and the World War II resistance leader Napoleon Zervas.[42]

Identity, ethnicity and language

In Ottoman-ruled Epirus, national identity did not play a role to the social classification of the local society; while religion was the key factor of classification of the local communities. The Orthodox congregation was included in a specific ethno-religious community under Graeco-Byzantine domination called Rum millet. Its name was derived from the Byzantine (Roman) subjects of the Ottoman Empire, but all Orthodox Christians were considered part of the same millet in spite of their differences in ethnicity and language. According to this, the Muslim communities in Epirus were classified as Turks, while the Orthodox (Rum), like the Souliotes, were classified as Greeks.[2][43][44] Moreover, national consciousness and affiliations were absent in Ottoman Epirus during this era.[2] Latter Greek official policy from the middle of the nineteenth century until the middle twentieth century, adopted a similar view: that speech was not a decisive factor for the establishment of a Greek national identity.[45] As such, the dominant ideology in Greece considered as Greek leading figures of the Greek state and obscured the links of some Orthodox people such as Souliotes had to the Albanian language.[45]

The Souliotes were also called Arvanites by Greek monolinguals,[46][47] which amongst the Greek-speaking population until the interwar period, the term Arvanitis (plural: Arvanites) was used to describe an Albanian speaker regardless of their religious affiliations.[48] It has been recognized, though, that speaking Albanian in that region “is not a predictor with respect to other matters of identity”.[49] After the rise of modern nationalism on the Balkans the Souliotes identified entirely with the Greek national cause.[50] On the other hand, due to their identification with Greece, they were considered Greeks by both their Ottoman and Muslim Albanian adversaries.[51] Moreover, religiously, they belonged to the Church of Constantinople, part of the larger Greek Orthodox Church.

19th- and 20th-century accounts

The Souliotes had a strong local identity. Athanasios Psalidas, a Greek scholar and secretary to Ali Pasha in early 19th century stated that the Souliotes were Greeks fighting the Albanians.[51] Moreover, Psalidas in reference to the Chams wrote that they are people of either Greek or Albanian origin, while the villages of Souli were inhabited by "Greek warriors".[52] Amongst Western European travelers and diplomats traveling in the region during the nineteenth century, they described the Souliotes in different terms and noted various observations regarding their language and customs. Lord Byron, writing in 1811, called them "Romans" who speak "little Illyric".[53] French diplomat François Pouqueville, while travelling the lands prior to 1813, called them a "Greek tribe", but asserted in his memoirs that the Souliotes weren't Greek, but rather Albanian by language, customs and origin.[6][54] Pouqueville also stated that their name derives from the ancient Greek tribe Selloi and their region was known as Selaida in antiquity.[5] Henry Holland, a British traveller passing through the area between 1812 and 1813 referred to the Souliotes as being of "Albanian origin" and "belonging to the division of that people called the Tzamides" or Chams.[55]

According to a Greek politician from the era Iakōbos Rizos-Nerulos, their maternal (primary) language was Greek and they also knew Albanian,[56] and they have thus also been referred to as "Albanian-speaking Greeks".[57] In the early 1840s, there were examples of Western travellers like James John Best hiring Souliotes to serve as guides while traversing the Balkans as they could speak "both Greek and Albanian, as well as the Italian and English languages".[58] In 1866, British traveller Emily Anne Beaufort while in the region described the Souliotes as belonging to the "Tchamides, or Southern Albanians" and that their association with the Greeks was due to educative, religious and linguistic hellenisation.[59] In 1869, British traveller Henry Fanshawe Tozer passing through the region referred to the Souliotes as belonging to the "Tchamides" that "spoke only the Albanian language", and in their capacity as "warriors... ruled and protected" the "Greek peasants" who cultivated the most fertile soil in Souli.[60] In the early 1880s, British diplomat and traveller Valentine Chirol when passing through the area came across people inhabiting Souli who "had spoken Greek as well as Albanian", while he placed the Souli region within the confines of the then Albanian-speaking region referred to as "Tchamouria" or Chameria.[61]

Historiography

Long after the Albanian migrations of the 15th century into central and southern Greece, newer waves of Albanian speaking populations such as the Souliotes migrated to Zagori in Greek Epirus, who before settling there spoke mostly Albanian.[46] Many of them were already bilingual upon their arrival in Zagori, due to the immigration of Greeks to Souli and the Albanian-speaking population within Souli, such as the valley of Souli (Lakka-Suliots) having close contact with the Greek-speaking population of the wider area (Para-Suliots).[46]

During the early nineteenth century Souliote exile in Corfu, the Souliote population was registered in official Corfiot documents as Arvanites, Albanesi or even Alvanites (Αλβανήτες) by individuals married into the Souliote community.[47][62] According to Greek Corfiot historian Spyros Katsaros, he states that the Corfiot Orthodox Greek speaking population during the period of 1804–14 viewed the Souliotes as "Albanian refugees ... needing to be taught Greek".[63] While K.D. Karamoutsos, a Corfiot historian of Souliote origin disputes this stating that the Souliotes were a mixed Graeco-Albanian population or ellinoarvanites.[62] Other Greek historians such as Vasso Psimouli state that the Souliotes were of Albanian origin, spoke Albanian at home and eventually became bilingual in Greek.[62] Thus in Greece today, the issue of ethnicity and origins regarding the Souliotes is contested and various views exist regarding whether they were Albanian, Albanian-speaking Greeks, or a combination of Hellenised Christian Albanians and Greeks who had settled in northern Greece.[62]

Other academic sources have inferred that they were Greek-speaking and of Albanian origin,[64][65] having originally spoken Albanian. Whereas some other academic sources have described the Souliotes as being "partly hellenized Albanian".[66] R. A. Davenport noted that some believed that the nucleus of the population consisted of Albanians, who had sought refuge in the mountains after the death of Skanderbeg, and that others believed that shepherds settled with their families in the late 17th century, or that they settled from Gardhiki fleeing from the Turks.[67] Scottish historian George Finlay called them a branch of Chams, which American ethnologist Laurie Kain Hart interpreted as them having initially spoken Albanian.[49] British academic Miranda Vickers calls them "Christian Albanians".[68] A NY Times article from 1880 calls them a "branch of the Albanian people".[69] The Canadian professor of Greek studies Andre Gerolymatos has described them as "branch of the southern Albanian Tosks" and "Christian Albanians of Suli".[70]

Written accounts of the Souliotic language

Further evidence on the language of the Souliotes is drawn from the Greek-Albanian dictionary composed in 1809 mainly by Markos Botsaris and his elders. Titos Yochalas who studied the dictionary concluded that either the mother tongue of the authors was Greek or the Greek language had a very strong influence on the local Albanian dialect, if the latter was possibly spoken in Souli.[71] Another written account on the language they used is the diary of Fotos Tzavellas, written during his captivity by Ali Pasha (1792–1793). This diary is written by F. Tzavellas himself in simple Greek with several spelling and punctuation mistakes. Emmanouel Protopsaltes, former professor of Modern Greek History at the University of Athens, who published and studied the dialect of this diary, concluded that Souliotes were Greek speakers originating from the area of Argyrkokastro or Chimara.[72][73] Amongst people who spoke the local Albanian dialect of the area during the Ottoman era, a high status was attributed to the Greek language and it functioned as a second semi-official language that was also used in documents.[74] In the early twentieth century within the Souliote community, there were examples of Souliote individuals still being fluent in the Albanian language like lieutenant Dimitrios (Takis) Botsaris, a direct descendant of the Botsaris' family.[74]

Souliotes in folk art and culture

The Souliotic wars against the Ottoman Turks and Muslim Albanians of Ali Pasha in late 18th and early 19th century is the theme of a number of folk songs. The first collection of Souliotic songs was published by the French philologist Claude Fauriel in 1824 in his “Chants populaires de la Grèce moderne”, a cornerstone for French and Greek laography.[75] (See Souliotic songs).

Theater plays and poems were produced during and soon after the Greek Revolution of 1821 for the Souliotes in general, and for certain heroes or events, such as Markos Botsaris or the Dance of Zalongo.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Souliotes. |

References

- ↑ Biris (1960: 285ff.) Cf. also K. Paparigopoulos (1925), Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Εθνους, Ε-146.

- 1 2 3 Nußberger Angelika; Wolfgang Stoppel (2001), Minderheitenschutz im östlichen Europa (Albanien) (PDF) (in German), p. 8: "war im ubrigen noch keinerlei Nationalbewustsein anzutreffen, den nicht nationale, sodern religiose Kriterien bestimmten die Zugehorigkeit zu einer sozialen Gruppe, wobei alle Orthodoxe Christen unisono als Griechen galten, wahrend "Turk" fur Muslimen stand..." [...all Orthodox Christians were considered as "Greeks", while in the same fashion Muslims as "Turks": Universität Köln

- ↑

- Balázs Trencsényi, Michal Kopecek: Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945): The Formation of National Movements. Central European University Press, 2006, ISBN 963-7326-60-X, S. 173. “The Souliotes were Albanian by origin and Orthodox by faith”.

- Giannēs Koliopoulos, John S. Koliopoulos, Thanos Veremēs: Greece: The Modern Sequel : from 1831 to the Present. 2. Edition. C. Hurst & Co., 2004, ISBN 1-85065-462-X, S. 184

- Eric Hobsbawm: Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. 2. Edition. Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-43961-2, S. 65

- NGL Hammond: Epirus: the Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas. Clarendon P., 1967, S. 31

- Richard Clogg: Minorities in Greece: Aspects of a Plural Society. Hurst, Oxford 2002, S. 178. [Footnote] “The Souliotes were a warlike Albanian Christian community, which resisted Ali Pasha in Epirus in the years immediately preceding the outbreak the Greek War of Independence in 1821.”

- Miranda Vickers: The Albanians: A Modern History. I.B. Tauris, 1999, ISBN 1-86064-541-0, S. 20. “The Suliots, then numbering around 12,000, were Christian Albanians inhabiting a small independent community somewhat akin to tat of the Catholic Mirdite trive to the north”.

- Nicholas Pappas: Greeks in Russian Military Service in the Late 18th and Early 19th Centuries. Institute for Balkan Studies. Monograph Series, No. 219, Thessaloniki 1991, ISSN 0073-862X.

- Katherine Elizabeth Fleming: The Muslim Bonaparte: Diplomacy and Orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-691-00194-4, S. 59. “The history of the Orthodox Albanian peoples of the mountain stronghold of Souli provides an example of such an overlap.”

- André Gerolymatos: The Balkan Wars: Conquest, Revolution, and Retribution from the Ottoman Era to the Twentieth Century and Beyond. Basic Books, 2002, ISBN 0-465-02732-6, S. 141. “The Suliot dance of death is an integral image of the Greek revolution and it has been seared into the consciousness of Greek schoolchildren for generations. Many youngsters pay homage to the memory of these Orthodox Albanians each year by recreating the event in their elementary school pageants.”

- Henry Clifford Darby: Greece. Great Britain Naval Intelligence Division. University Press, 1944. “… who belong to the Cham branch of south Albanian Tosks (see volume I, pp. 363-5). In the mid-eighteenth century these people (the Souliotes) were a semi-autonomous community …”

- Arthur Foss (1978). Epirus. Faber. pp. 160-161. “The Souliots were a tribe or clan of Christian Albanians who settled among these spectacular but inhospitable mountains during the fourteenth or fifteenth century…. The Souliots, like other Albanians, were great dandies. They wore red skull caps, fleecy capotes thrown carelessly over their shoulders, embroidered jackets, scarlet buskins, slippers with pointed toes and white kilts.”

- Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer (1983), "Of Suliots, Arnauts, Albanians and Eugène Delacroix". The Burlington Magazine. p. 487. “The Albanians were a mountain population from the region of Epirus, in the north-west part of the Ottoman Empire. They were predominantly Muslim. The Suliots were a Christian Albanian tribe, which in the eighteenth century settled in a mountainous area close to the town of Jannina. They struggled to remain independent and fiercely resisted Ali Pasha, the tyrannic ruler of Epirus. They were defeated in 1822 and, banished from their homeland, took refuge in the Ionian Islands. It was there that Lord Byron recruited a number of them to form his private guard, prior to his arrival in Missolonghi in 1824. Arnauts was the name given by the Turks to the Albanians”.

- ↑ Camaj, Martin, & Leonard Fox (1984). Albanian grammar: with exercises, chrestomathy and glossaries. Otto Harrassowitz - Verlag. p. 20. "Patronymics in –ot are also included in this category: indef. sg. suljot ‘native of Suli’ – indef. pl. suljótë."

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nicholas Charles Pappas (1991). Greeks in Russian Military Service in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries. Institute for Balkan Studies. p. 39.

"Souli gave its name to the confederation, a name whose origins are also unclear. Francois Pouqeville, the French traveller and consul in Ioannina, and other have theorized that the area was the ancient Greek Selaida and its ihnabitants, the Selloi. Christophoros Perraivos, who knew the Souliotes at firsthand, said that the name came from a Turk who was killed there. Yet another opinion, based on etymology, claims that Souli comes from the Albanian term sul,

- 1 2 Pouqueville 1813, p. 392.

- ↑ Babiniotis, G. Λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας. Athens, 1998.

- ↑ Petros Fourikis (1922). Πόθεν το όνομά σου Σούλι, Ημερολόγιον της Μεγάλης Ελλάδος. pp. 405-406. “Αί κυριώτεραι κορυφαί, έφ' ών έγκατεστάθησαν οί μέχρις αύτών άναρριχηθέντες ολίγοι φυγάδες τής τουρκικής τυραννίδος, οί μετέπειτα ήρωες οί τρομοκρατήσαντες τούς πρό μικρού κυρίους αύτών, είναι γνωσταί ύπό τά άλβανικά ονόματα Άβαρίκο, Κιάφα (λαιμός, ζυγός, κλεισώρεια), Σαμονίβα (κρανιά ίσως) καί Σούλη aί δέ συνεχείς ταύταις κορυφαί είναι μέχρις ήμών γνωσταί ύπό τά ονόματα Βίρα ή Μπίρα (τρύπα), Βούτζι (άβρότονον, φυτόν), Βρέκου - η - Βετετίμεσε (βράχος τής αστραπής), Γκούρα (βράχος ή πηγή έκ τού βράχου ανάβλυζουσα), Δέμπες (δόντια ή οδοντωτός βράχος), Κούγγε (πασσάλοι ή βράχος έχων όψιν πασσάλων), Μούργκα, Στρέτεζα ή Στρέθεζα (μικρών οροπέδιον) καί Φέριζα (μικρά βάτος). Έκ τής μέχρι τούδε έρεύνης τών τοπωνυμίων τού βραχώδους έκείνου συμπλέγματος έπείσθην, ότι ούδέν έλληνικών όνομα εδόθη είς θέσιν τινά τούτου, διότι καί τά υπό τινων άναγραφόμενα τοπωνύμια: Αγία Παρασκευή, Αστραπή καί Τρύπα ούδέν άλλο είναι εί μή μετάφρασις τών άλβανικών Σεν - η - Πρέμπτε, Βετετίμε καί Βίρα. Περί τών έξω τού ορεινών τούτου χώρων καί πρός τά μεσημβρινά κράσπεδα αύτών άναφερόμενων θέσεων Βίλγα (Βίγλα) καί Λάκκα (κοιλάς) δύναταί τις νά είπη, ότι αί λέξεις κοιναί ούσαι τοίς τε Έλληση καί τοίς Άλβανοίς δέν δύνανται νά μαρτυρήσωσιν άναμφισβητήτως περί τής ύφ' Έλλήνων ονομασίας τών θέσεων τούτων.”

- 1 2 Biris, K. Αρβανίτες, οι Δωριείς του νεότερου Ελληνισμού: H ιστορία των Ελλήνων Αρβανιτών. ["Arvanites, the Dorians of modern Greece: History of the Greek Arvanites"]. Athens, 1960 (3rd ed. 1998: ISBN 960-204-031-9).

- ↑ Megale Hellenike Encyclopedia (I. Drandakis Encyclopedia), c. 1935, article "Souli"/history (Σούλι/ιστορ.): "Ο Περραιβός όμως, ο και μόνος δυνάμενος να έχη την πλέον έγκυρον γνώμην, ως επί έτη αναστραφείς μετά των Σουλιωτών, λέγει ότι, ως ήκουσε παρά γερόντων Σουλιωτών, οι πρώτοι οικισταί του Σουλίου μετώκισαν κατά διαστήματα από του 1500-1600 εκ των πέριξ χωρίων, αποφεύγοντες την τουρκικήν δουλείαν."

- ↑ Hart 1999, p. 202.

- ↑ Leake W. Travels in Northern Greece, London, 1835, vol. 1, p. 502.

- ↑ Miranda Vickers, The Albanians: A Modern History, I.B.Tauris, 1999, ISBN 1-86064-541-0, ISBN 978-1-86064-541-9 "The Souliots, then numbering around 12,000, were Christian Albanians inhabiting a small independent community somewhat akin to that of the Catholic Mirdite tribe to the north.

- ↑ PDF "(875 KB) 2001 Census" (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece (ΕΣΥΕ). www.statistics.gr. Retrieved on 2007-10-30.

- ↑ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ ΤΟΥ ΣΟΥΛΛΙΟΥ ΚΑΙ ΠΑΡΓΑΣ, συγγ. παρά ΧΡΙΣΤΟΦΟΡΟΥ ΠΕΡΡΑΙΒΟΥ. Εν Αθηναίς. 1857. p. 2

- ↑ Kapralos, Ch. Αρκαδικοί θρύλοι. p. 160. Η οικογένεια του Αντωνόπουλου (Μποτσαραίοι) κατάγονται από το Σούλι σύμφωνα με κάποια παράδοση.

- ↑ Kapralos, Ch. Αρκαδικοί θρύλοι. p. 70. Μα και οι Καπραλαίοι, προερχόμενοι από την Ήπειρο, έμειναν στη Μεσσηνία για κάποιο χρονικό διάστημα.

- ↑ Tzavaras, Ath.: "Agapite Aderfe Vasileie", Ekdosis Exantas, Athens 1999.

- ↑ The National Historical Museum. Euthymia Papaspyrou-Karadēmētriou, Maria Lada-Minōtou, Ethniko Historiko Mouseio (Greece). Historical and Ethnological Society of Greece, 1994. ISBN 960-85573-0-5

- 1 2 3 4 5 Davenport 1837, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 Vranousis, L, Sfyroeras, V. (1997). "From the Turkish Conquest to the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century". Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization: 247. ISBN 9789602133712.

At the end of the seventeenth century, during the course of the Venetian-Turkish War of 1684–1689, the Venetian successes in the Ionian Sea rekindled the revolutionary flame in Cheimara and Souli, where the first reference to anti-Turkish activity on the part of the inhabitants goes back to this period, more specifically to 1685: the overthrow, albeit temporary, of Turkish domination over the villages around the inaccessible area of Souli provoked an immediate reaction on the part of the beys, agas and pashas of the area... We have concrete evidence for the attempts of the Porte to crush the resistance of the indomitable Souliots from the third decade of the eighteenth century. In 1721, when the Souliots rejected his proposal that they should submit, the pasha of Ioannina, Zadji Ahmed laid siege to Souli with a strong force, but was obliged to withdraw after a night attack by the besieged. A fresh uprising by the Souliots and the villagers of Margariti in Thesprotia in 1732, was instigated by the Venetians, to whom the Treaty of Passarowitz (1718) had ceded the coastal zone of Epirus from Bouthro- tos to Parga and Preveza.... The Souliotes and the inhabitants of other Epiroete regions also mobilized on a considerable scale "during the Or- lov Incident, as the uprising of the Greeks during the first Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774) is known. At the beginning of February... A few months later, in March 1789, the chieftains of Souli Giorgis and Demetris Botsaris, Lambros Tzavellas, Nicholas and Christos Zervas, Lambros Koutsonikas, Christos Photomaras and Demos Drakos wrote to Sotiris declaring that they and their 2,200 men were ready to fight against Ali Pasha and "the Agarenoi in Roumeli". Ali, who had succeeded Kurt Pasha in the pashalik of Epirus in spring 1789, was informed about the movements of the Souliots, and immediately organized a campaign against them.

- ↑ Χατζηλύρας, Αλέξανδρος-Μιχαήλ. "H Ελληνική Σημαία. H ιστορία και οι παραλλαγές της κατά την Επανάσταση - Η σημασία και η καθιέρωσή της." (PDF). Hellenic Army General Stuff. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ Rados N. Konstantinos, Souliotes and Armatoloi in the Septinsular (1804–1815). The Legion of the "Light Riflemen" - The "Albanian Regiment" - The two regiments of the "Light Greek Infantry of the Duke of York". Athens, 1916, pp. 47, 48.

Ράδος N. Κωνσταντίνος, Οι Σουλιώται και οι Αρματωλοί εν Επτανήσω (1804–1815). Η Λεγεών των "Ελαφρών Κυνηγετών" - Το "Αλβανικόν Σύνταγμα" - Τα δύο συντάγματα του "ελαφρού ελληνικού πεζικού του δουκός της Υόρκης". Αθήναι, 1916, pp. 47, 48 - ↑ Legrand Emile, Bibliographie Ionienne ... des ouvrages publies par les Grecs des Sept-Iles. Paris, 1910, vol. 1, pp. 202, 203, article 699.

- 1 2 3 Nicholas Charles Pappas, Greeks in Russian Military Service in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries, Institute for Balkan Studies, 1991

- 1 2 Banac, Ivo; Ackerman, John G.; Szporluk, Roman; Vucinich, Wayne S. (1981). Nation and ideology: essays in honor of Wayne S. Vucinich. East European Monographs. p. 42.

- ↑ Bode, Andreas (1975). «Albaner und Griechen als Kolonisten in Neurussland"», Beitrage zur Kenntnis Sudosteuropas und des Nahen Orients, Munchen, vol. 16 (1975), pp. 29-35, cited in: Les Grecs en Russie/Les colonies militaires, Oct. 1995, by Sophie Dascalopoulos (Prof.) – Vernicos Nicolas (Prof.)"We remark that the term "Albanian" is not an ethnic qualification but, as the terms "Zouave" and "Dragon", is used as generic to certain corps of infantry, formations of mercenaries recruited among christians of Turkey. The Albanian Regiments were used also by the Italians and the French".

- ↑ Boppe Auguste, Le Régiment Albanais (1807–1814), Berger-Levrault & Cie, Paris, 1902. p. 11.

- ↑ Skiotis, 1976, p. 105-106: Ali's appeals were, of course, addressed primarily to the Kapitanioi of the Greek contigents in the Ottoman army. In addition, however, to the detachments of armatoloi already in the mainland, there were also numerous klephs and mountain tribesmen such as the Souliotes who had crossed over from the Ionian islands to Epirus at Ottoman invitation. There had been over, 3,000 of these fighting men in the islands, men who had been forced from Ali's dominions as he had gradually extended his rule over Rumeliy. While in exlie they had served under the banner of whichever power held the islands, but the British had disbanded their regiments at the end of the Napoleonic wars. Unable any longer to maker their living as soldiers, they were destitute and bitter group which longed for some radical change in their political situation that would enable them to return to their homeland. Kapodistrias, a native Corfiote serving as Russian foreign minister, who knew of the exiled chieftains from visiting the island in 1819, was extremely concerned about their plight and suspected that the British on the island and Ali Pasha on the mainland were acting in concert to destroy what we might call the “military” Greeks. When both Ali Pasha and the Ottomans had requested their assistance in the summer of 1820, it was Kapodistrias who had encouraged them to take advantage of this opportunity to regain their ancestral villages. In fact, though certainly no revolutionary himself, who had been chosen by the Hetaireia, that he endorsed the right of the military “Greeks” - “those Greeks who bear arms”- to defend themselves against whatever for attacked them, “as they have done for centuries”... It was not realistic to assume that the people would remain uninvolved while the military Greeks did battle with the Ottomans.

- ↑ Skiotis, 1976, p. 106: Not surprisingly, the warlike and independent Souliotes, who like the other Greeks had been repeatedly mistreated by the Ottoman who were especially close to the Kapodistrias brothers, were the first to rebel against the sultan (on 7/19 December) and ally themselves with Ali Pasha. They undoubtedly knew of the Hetaireia (as did everybody else by this time) but their purpose in revolting was most probably of a local nature: to regain the barren villages they had been forced to abandon seventeen years before...

- ↑ Skoulidas, Ilias (2001). "The Relations Between the Greeks and the Albanians during the 19th Century: Political Aspirations and Visions (1875 - 1897)". www.didaktorika.gr (in Greek). University of Ioannina: 17. doi:10.12681/eadd/12856. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

... Οι συνεννοήσεις Σουλιωτών και μουσουλμάνων Αλβανών για την υπεράσπιση του Αλή πασά, οι οποίες οδήγησαν σε γραπτή συμφωνία (15/27 Ιανουαρίου 1821) στο Σούλι, ήταν σύμφωνες με τις θέσεις του Αλέξανδρου Υψηλάντη για την προετοιμασία της ελληνικής επανάστασης.

- ↑ Fleming, Katherine Elizabeth (1999), The Muslim Bonaparte: diplomacy and orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece, Princeton University Press, pp. 59, 63, ISBN 978-0-691-00194-4, retrieved 19 October 2010

- ↑ M. V. Sakellariou (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotikē Athēnōn. p. 273. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- ↑ Skiotis, 1976, p. 106-107: “The news of the rising of the most famous and heroic among the Greeks could not fail but spread like wildfire through the land.

- ↑ Skiotis, 1976, p. 106-107: “The news of the rising of the most famous and heroic among the Greeks could not fail but spread like wildfire through the land. Kasomoules, a contemporary memoirist, recalls that “the trumpet sounded from the north in the month of December and all Greeks, even in the most remote places were inspired by its call.” “If ever the cry of liberty is heard in Greece,” wrote the French concul in Patras, “it will come from the mountains of Epirus! According to all indications the moment has arrived.” Soon there were other Greek fighting men form the Ottoman camp and neighboring mountain tribesmen joined with the Souliotes. In January even the Muslim Albanians, who had enjoyed a privileged position during Ali's rule, and resented Ottoman oppression as mush as the Greeks, signed a formal pact with the Souliotes.”

- ↑ Skiotis, 1976, p. 107: “In fact the astonishing progress of Greek arms in Epirus and the solidarity between the kapetanaioi there and Ali Pasha seems to have taken the top Hetairists in the Ottoman capital and Russia by surprise.”

- 1 2 Roudometof & Robertson 2001, p. 25.

- ↑ Brigands with a Cause, Brigandage and Irredentism in Modern Greece 1821–1912, by John S. Koliopoulos, p. 59. Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1987. ISBN 0-19-822863-5

- ↑ University of Chicago (1946), Encyclopædia britannica: a new survey of universal knowledge, Volume 3, Encyclopædia britannica, inc, p. 957,

Marco Botsaris’s brother Kosta (Constantine), who fought at Karpenisi and completed the victory, lived to become a general and senator in the Greek Kingdom. Kosta died in 1853..

- ↑ Baumgart Winfried. Englische Akten zur Geschichte des Krimkriegs. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2006. ISBN 978-3-486-57597-2, p. 262

- ↑ University of Chicago. Encyclopædia britannica: a new survey of universal knowledge. Encyclopædia britannica, inc., 1946, p. 957

- ↑ Alexandros L. Zaousēs, Hetairia Meletēs Hellēnikēs Historias. Οι δύο όχθες, 1939–1945: μία προσπάθεια για εθνική συμφιλίωση. Ekdoseis Papazēsē, 1987, p. 110.

- ↑ In the late 1790s, Balkan Orthodox Christians routinely referred to themselves as “Christians”. Within the Ottoman Empire, these Greek Orthodox urban and mercantile strata were referred to by the Ottomans, the Church, and themselves as Rayah, Christians, or “Romans”, that is, members of the Rum millet. The name Roman was a legacy of history, not a factual identification of race or ethnicity. The term Roman originally designated a citizen of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Ottomans employed the term Rayah to imply all land cultivators regardless of religion; but in practice, in the Ottoman Balkans, this term meant the Orthodox Christians. For the Western audience in Germany, Austria, and Hungary, Greek Orthodox was synonymous with Orthodoxy. From Rum Millet to Greek Nation: Enlightenment, Secularization, and National Identity in Ottoman Balkan Society, 1453–1821, Victor Roudometof, p. 19

- ↑ Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers; Bernd Jürgen Fischer (2002). Albanian Identities: Myth and History. Indiana University Press. pp. 50–. ISBN 0-253-34189-2.

- 1 2 Baltsiotis. The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece. 2011. "The fact that the Christian communities within the territory which was claimed by Greece from the mid-19th century until 1946, known after 1913 as Northern Epirus, spoke Albanian, Greek and Aromanian (Vlach), was dealt with by the adoption of two different policies by Greek state institutions. The first policy was to take measures to hide the language(s) the population spoke, as we have seen in the case of “Southern Epirus”. The second was to put forth the argument that the language used by the population had no relation to their national affiliation. To this effect the state provided striking examples of Albanian speaking individuals (from southern Greece or the Souliotēs) who were leading figures in the Greek state. As we will discuss below, under the prevalent ideology in Greece at the time every Orthodox Christian was considered Greek, and conversely after 1913, when the territory which from then onwards was called “Northern Epirus” in Greece was ceded to Albania, every Muslim of that area was considered Albanian."

- 1 2 3 Thede Kahl (1999). "Die Zagóri-Dörfer in Nordgriechenland: Wirtschaftliche Einheit–ethnische Vielfalt [The Zagori villages in Northern Greece: Economic unit - Ethnic diversity]". Ethnologia Balkanica. 3: 113-114. "Im Laufe der Jahrhunderte hat es mehrfach Ansiedlungen christlich-orthodoxer Albaner (sog. Arvaniten) in verschiedenen Dörfern von Zagóri gegeben. Nachfolger Albanischer Einwanderer, die im 15. Jh. In den zentral- und südgriechischen Raum einwanderten, dürfte es in Zagóri sehr wenige geben (Papageorgíu 1995: 14). Von ihrer Existenz im 15. Jh. wissen wir durch albanische Toponyme (s. Ikonómu1991: 10–11). Von größerer Bedeutung ist die jüngere Gruppe der sogenannten Sulioten – meist albanisch-sprachige Bevölkerung aus dem Raum Súli in Zentral-Epirus – die mit dem Beginn der Abwanderung der Zagorisier für die Wirtschaft von Zagóri an Bedeutung gewannen. Viele von ihnen waren bereits bei ihrer Ankunft in Zagóri zweisprachig, da in Súli Einwohner griechischsprachiger Dörfer zugewandert waren und die albanischsprachige Bevölkerung des Súli-Tales (Lakka-Sulioten) engen Kontakt mit der griechischsprachigen Bevölkerung der weiteren Umgebung (Para-Sulioten) gehabt hatte (Vakalópulos 1992: 91). Viele Arvaniten heirateten in die zagorische Gesellschaft ein, andere wurden von Zagorisiern adoptiert (Nitsiákos 1998: 328) und gingen so schnell in ihrer Gesellschaft auf. Der arvanitische Bevölkerungsanteil war nicht unerheblich. Durch ihren großen Anteil an den Aufstandsbewegungen der Kleften waren die Arvaniten meist gut ausgebildete Kämpfer mit entsprechend großer Erfahrung im Umgang mit Dörfer der Zagorisier zu schützen. Viele Arvaniten nahmen auch verschiedene Hilfsarbeiten an, die wegen der Abwanderung von Zagorisiern sonst niemand hätte ausführen können, wie die Bewachung von Feldern, Häusern und Viehherden."

- 1 2 Raça, Shkëlzen (2012). "Disa Aspekte Studimore Mbi Sulin Dhe Suljotët [Some research aspects regarding Souli and the Souliotes]". Studime Historike. 1. (2): 215. "Αλβανήτες", d.m.th., shqiptare i identifikon edhe Eleni Karakicu, bashkëshortja e pare e Marko Boçarit. Ajo në fakt drejton një kundër akuzë ndaj tij e familjes së tij, si përgjigje rreth një procesi gjyqësor për çështje shkurorëzimi të parashtruar nga vetë Marko Boçari më 1810, në shtatë ujdhesat e Detit Jon. Ndërmjet tjerash, Karakicu akuzon indiferencën e vjehrrive të saj me fjalët: Nëse ai i kishte të gjitha gjërat në duart e veta, se vjehrri dhe vjehrra ime nuk vendosen ta zënë e ta vrasin, sa Kostën e Stathit, po aq edhe këtë ta bëjnë per mua dhe se sipas tyre e kanë tradhtuar, atëherë veprimi i tillë është borxh dhe ligj për shqiptarët, që të lahen nga mëkati. Më gjerësisht: T.A.K, Arkivi i Rrethit të Korfuzit, Fondi "Mitropoliti" Akti 189. Gjithashtu, si "arvanitë", ata identifikohen edhe në katalogët onomastike të të huajve në Korfuz, një pjesë e të cilëve figurojnë si banorë të fshatrave: Strugli, Stavro e Benica. Më gjerësisht: T.A.K, Arkivi i rrethit të Korfuzit - Të dhëna për të huajt, Raporti 59, dhjetor 1815." "["Alvanites", or in other words Albanians is how Eleni Karakitsou, the wife of Markos Botsaris identifies them. It relates to an accusation against his family to answer questions in a divorce case trial filed by Markos Botsaris in 1810 in the Septinsular islands of the Ionian Sea. Among other things, Karakitsou accuses her in laws of indifference with the words: He had everything in his hands, because my father in law and mother in law decided not catch and to kill him, like Kosta and Stathi, yet they did not do this for me and I believe they have betrayed me and such an action is owed and law for Albanians, so as to brush away those sins". For more: T.A.K. Archive of the municipality of Corfu, Fund "Mitropoliti" Act 189. Also, "Arvanites" as they are identified in the onomastic catalogs for foreigners in Corfu, some of whom are mentioned as inhabitants of the villages: Strougli, Stavro and Benica. For more: T.A.K. Archive of the municipality of Corfu - Data on foreigners, Report 59 December 1815.]"

- ↑ Baltsiotis, Lambros (2011). The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece: The grounds for the expulsion of a "non-existent" minority community. European Journal of Turkish Studies. "Until the Interwar period Arvanitis (plural Arvanitēs) was the term used by Greek speakers to describe an Albanian speaker regardless of his/hers religious background. In official language of that time the term Alvanos was used instead. The term Arvanitis coined for an Albanian speaker independently of religion and citizenship survives until today in Epirus (see Lambros Baltsiotis and Léonidas Embirikos, “De la formation d’un ethnonyme. Le terme Arvanitis et son evolution dans l’État hellénique”, in G. Grivaud-S. Petmezas (eds.), Byzantina et Moderna, Alexandreia, Athens, 2006, pp. 417-448."

- 1 2 Hart 1999, "Finlay's late 19th century impression gives some impressions of the social complexity of social categories in this area. To begin with, the Souliotes (celebrated by Byron and in Greek national history for their role in the liberation of Greece) were a "branch of the Tchamides, one of the three great divisions of the Tosks" (Finlay 1939:42)-in other words they initially spoke Albanian... the question of a national identity can hardly be applied here"

- ↑ Banac, Ivo; Ackerman, John G.; Szporluk, Roman; Vucinich, Wayne S. (1981). Nation and ideology: essays in honor of Wayne S. Vucinich. East European Monographs. p. 44.

- 1 2 Nikolopoulou, Kalliopi (2013). Tragically Speaking On the Use and Abuse of Theory for Life. Lincoln: UNP - Nebraska Paperback. p. 299. ISBN 9780803244870.

Still, regardless of ethnic roots, the Souliot identification with Greece earned them the title of "Greeks" by their Ottoman and Muslim Albanian enemies alike... identifies them as Greeks fighting the Albanians

- ↑ Kallivretakis, Leonidas (1995). "Η ελληνική κοινότητα της Αλβανίας υπό το πρίσμα της ιστορικής γεωγραφίας και δημογραφίας [The Greek Community of Albania in terms of historical geography and demography." In Nikolakopoulos, Ilias, Kouloubis Theodoros A. & Thanos M. Veremis (eds). Ο Ελληνισμός της Αλβανίας [The Greeks of Albania]. University of Athens. p. 36, 47: "Οι κατοικούντες εις Παραμυθίαν και Δέλβινον λέγονται Τζαμηδες και ο τόπος Τζαμουριά», δίδασκε ο Αθανάσιος Ψαλίδας στις αρχές του 19ου αιώνα και συνέχιζε: «Κατοικείται από Γραικούς και Αλβανούς· οι πρώτοι είναι περισσότεροι», ενώ διέκρινε τους δεύτερους σε Αλβανούς Χριστιανούς και Αλβανούς Μουσουλμάνους." Στην Τσαμουριά υπάγει επίσης την περιφέρεια της Πάργας, χωρίς να διευκρινίζει τον εθνοπολιτισμικό της χαρακτήρα, καθώς και τα χωριά του Σουλίου, κατοικούμενα από «Γραικούς πολεμιστές».

- ↑ Byron to Hobhouse, letter from 8, St James’s Street, London, November 2nd 1811:“… The Suliotes are villainous Romans & speak little Illyric.”

- ↑ Pouqueville, Francois. Mémoires sur la Grèce et l'Albanie pendant le gouvernement d'Ali-Pacha. p. 14.

- ↑ Henry Holland (1815). Travels in the Ionian Isles, Albania, Thessaly, Macedonia, &c., during the years 1812 and 1813. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown. p. 448. “They were Albanians in origin, belonging to the division of that people called the Tzamides. While many of their countrymen had become Mohametans, the Suliotes retained the Christian religion.”

- ↑ Iakōbos Rizos-Nerulos (1834). Histoire de l'Insurrection Grecque, precédée d'un précis d'Histoire moderne de la Grèce. Cherbulier. p. 156.

- ↑ Charles Jelavich; Barbara Jelavich (1963). The Balkans in Transition: Essays on the Development of Balkan Life and Politics Since the Eighteenth Century. University of California Press. pp. 13–141. GGKEY:E0AY24KPR0E.

... a common language was not sufficient to cement an alliance between Muslim Albanians and Albanian-speaking Greeks, such as the Souliotes, ...

- ↑ John Best, James (1842). Excursions in Albania; Comprising a Description of the Wild Boar, Deer, and Woodcock Shooting in that Country; and a Journey from Thence to Thessalonica & Constantinople, and Up the Danube to Pest. Wm. H. Allen & Co. p. 2. “Having accordingly made our arrangements, and hired as a travelling servant Giovanni Zaruchi, a native of Suli, in Albania, well acquainted with the country we wished to visit, and speaking both Greek and Albanian, as well as the Italian and English languages”.

- ↑ Anne Beaufort Smythe Strangford, Emily (1864). The eastern shores of the Adriatic in 1863. With a visit to Montenegro. Richard Bentley. p. 42. “The Suliotes were originally a simple family or clan of the Tosks (Southern Albanians) …. *From Finlay to Leake. It is a strangely common thing to find persons talking of the Suliotes as if they had been true Greeks; they were Albanians pure and simple, and had nothing to do with the Greek nation beyond communion with the Greek church, and the use of Greek as the language of writing, of education as far as it existed, and of the church. But these causes tended to Hellenise them more and more during their entire career. Some few from other Christian clans had joined the Suliotes, but they were all Tchamides, or Southern Albanians”.

- ↑ Tozer, Henry Fanshawe (1869). Researches in the highlands of Turkey; including visits to mounts Ida, Athos, Olympus, and Pelion, to the Mirdite Albanians, and other remote tribes. Volume II. John Murray. p. 184. "Now the province of southern Albania, that is the country south of the parallel of Argyro-Castro, may be regarded as divided in two parts in respect of race, by a line drawn at first south-eastwards in the direction of Yanina, and then directly southwards to Prevyza at the mouth of the Gulf of Arta. To the east of this line, including all the neighbourhood of Yanina, and the valleys of Arta and Aspropotamo, the population is purely Greek; to the west it is composed of two elements, Greek and Albanian, and the people speak both those languages, though one or the other is more familiar to them, according to the predominant element in their race. Thus the Suliots, whose territory was the knot of mountains in the southern part of this division, and who are so famous for their heroic resistance to Ali Pasha, were pure Albanians, and in their families spoke only the Albanian language. In this case the confusion has been the greater, because from their having been regarded as Greeks, their deeds of valour have often been introduced in connection with Hellenic intrepidity and patriotism."; p.210. "The Suliotes were a body of Christian Albanians, who mustered some 1500 warriors when at the height of their fortunes, and were independent of the Porte as the Mirdites are at the present day. They belonged to the tribe of the Tchamides, and in accordance with the usual strength and exclusiveness of feeling amongst the Albanians, they found their bitterest opponents in the members of another Toskish tribe, the Liapides during their struggle with Ali". ; pp. 210-211."The soil in the richest part of their territory was cultivated by peasants who were of the Greek race, while the Albanian warriors ruled and protected them, as the ancient Spartans did their agricultural population." ; p. 211. "Their community became a refuge for other Christians of the tribe of the Tchamides, and when about the middle of the century, in consequence of this protection which they extended to others, they became involved in feuds with their Mussulman neighbours, they recruited their forces by admitting every daring and active young Christian of that tribe to serve in their ranks." ; p. 213. "The hero of Suli was a priest named Samuel, who had assumed the strange cognomen of ‘The Last Judgement’. It was said that he was an Albanian, from the northern part of the island of Andros; but appears to have concealed his origin."

- ↑ Chirol, Valentine (1881). Twixt Greek and Turk. W Blackwood & sons. pp. 218-219. “My faith in my Greek friends of Yanina, who had assured me that south of the Kalamas there were no Albanian whom at least the bond of a common tongue did not unite to Greece, was first shaken. My hosts up at Suli had spoken Greek as well as Albanian".; pp. 231-232. "The limits of the Albanian-speaking districts of Epirus south of the Kalamas may be roughly defined as follows: Starting from the Kalamas near the sharp bend which that river takes to the north at the foot of Mount Lubinitza, they follow the crest of the amphitheatrical range of Suli as far as the gorge of the Acheron. In that neighbourhood, probably owing to the influence which the Suliote tribe at one time enjoyed, they drop over to the east into the valley of the Luro, and follow its basin as far as the peninsula on which Prevesa, is situated, where the Greek element resumes its preponderancy. Within these outer limits of the Albanian tongue the Greek element is not unrepresented, and in some places, as about Paramythia, for instance, it predominates; but, on the whole, the above- defined region may be looked upon as essentially Albanian. In this, again, there is an inner triangle which is purely Albanian—viz., that which lies between the sea and the Kalamas on the one hand and the waters of the Vuvo on the other. With the exception of Parga and one or two small hamlets along the shore, and a few Greek chifligis on Albanian estates, the inhabitants of this country are pure Tchamis—a name which, notwithstanding Von Hahn’s more elaborate interpretation. I am inclined to derive simply from the ancient appellation of the Kalamas, the Thyamis, on both banks of which stream the Albanian tribe of the Tchamis, itself a subdivision of the Tosks, has been settled from times immemorial. From the mountain fastnesses which enclose this inner triangle, the Tchamis spread out and extended their influence east and south; and the name of Tchamouria, which is especially applied to the southernmost Albanian settlements in Epirus, was probably given to that district by themselves as an emphatic monument of their supremacy; but it cannot belong less rightfully to the centre, where they hold undivided sway."

- 1 2 3 4 Potts, Jim (2014). "The Souliots in Souli and Corfu and the strange case of Photos Tzavellas". In Hirst, Anthony, & Patrick Sammon, (eds). The Ionian Islands: Aspects of Their History and Culture. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 107-108. "While the Corfiot historian, K. D. Karamoutsos, in his study of Souliot genealogies (or lineages) does not disagree on the question of the vendetta, he has little time for what he considers extensive “misinformation” on the part of Katsaros. Karamoutsos has a more sympathetic view of the Souliots, insisting that no respectable historian could categorize them as members of the Albanian nation simply on the grounds that they had their roots in the centre of present-day Albania and could speak the Albanian language. On the contrary, he argues, they were 100% Orthodox and bilingual, speaking Greek as well as Albanian; he says that their names, customs, costumes and consciousness were Greek, and that they maintained Greek styles of housing and family structures. He accepts that some historians might place their forbears in the category of akrites, or border guards, of the Byzantine Empire. When they came to Corfu, the Souliots were usually registered in official documents, he says, as Albanesi or Suliotti. They were, he concludes, a special group, a Greek-Albanian people (ellinoarvanites). Vasso Psimouli, on the other hand, takes for granted that the Souliots were of Albanian origin. According to her, they first settled in Epirus at the end of the fourteenth century, but they were not cut off from the Greek-speaking population around them. They spoke Albanian at home but they soon began to use Greek. As these varying opinions suggest, Greek academics have not been able to agree whether the Souliots were Albanian, Albanian-speaking Greeks, or a mixture of Greeks and Hellenized Christian Albanians who had settled in northern Greece. The issue of the origin and ethnicity of the Souliots is very much a live and controversial issue in Greece today."

- ↑ Jim Potts (October 12, 2010). "VI". The Ionian Islands and Epirus: A Cultural History. Landscapes of the Imagination. Oxford University Press, US. p. 186. ISBN 978-0199754168. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

Spiros Katsaros argues (1984) that the Suliots were much better off in Corfu, anyway. To the Corfiots, he suggests, in the period 1804–14, the Suliots were simply armed Albanian refugees, who were displacing them from their properties ... foreigners required to be housed at a short notice, prepared to squat illegally whenever necessary, needing to be taught Greek ... On these questions Katsaros is at odds with another Corfiot writer about the Suliots (himself of Suliot origins), D. Karamoutsos.

- ↑ Katherine Elizabeth Fleming (1999). The Muslim Bonaparte: Diplomacy and Orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0-691-00194-4.

The Souliotes, a Greek-speaking tribe of Albanian origin

- ↑ Balázs Trencsényi, Michal Kopecek. Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945): The Formation of National Movements, Published by Central European University Press, 2006, ISBN 963-7326-60-X, 9789637326608 p. 173 "The Souliotes were Albanian by origin and Orthodox by faith"

- ↑ Giannēs Koliopoulos, John S. Koliopoulos, Thanos Veremēs. Greece: The Modern Sequel : from 1831 to the Present Edition: 2 Published by C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2004 ISBN 1-85065-462-X, 9781850654629 p. 184 describes Souliotes as "Orthodox and partly hellenized Albanian tribes".

- ↑ Davenport 1837, p. 89.

- ↑ Miranda Vickers, The Albanians: A Modern History, I.B.Tauris, 1999, ISBN 1-86064-541-0, ISBN 978-1-86064-541-9 "The Suliots, then numbering around 12,000, were Christian Albanians inhabiting a small independent community somewhat akin to that of the Catholic Mirdite trive to the north

- ↑ Brave Women, NY Times, February 8, 1880,

The extraordinary courage of the Albanian women has been displayed over and over again in the history of the country; but one of the most celebrated instances was that recorded of the branch of the Albanian people represented by the Suliotes, when they were besieged by Ali Pasha in 1792.

- ↑ The Balkan Wars, Andre Gerolymatos, Basic Books, 2008, ISBN 0786724579, p. 187.

- ↑ Yochalas Titos (editor, 1980) The Greek-Albanian Dictionary of Markos Botsaris. Academy of Greece, Athens 1980, p. 53. (in Greek):

"Η παρουσία αύτη φαινομένων της ελληνικής συντάξεως εις το αλβανικόν ιδίωμα του Λεξικού είναι δυνατόν να ερμηνευθή κατά δύο τρόπους:- α) Ότι η μητρική γλώσσα του Μπότσαρη και των συνεργατών του ήτο η Ελληνική, ...

- β) Είναι δυνατόν επίσης δυνατόν η επίδρασις της ελληνικής γλώσσης να ήτο τόσον μεγάλη επί της Αλβανικής της ομιλουμένης πιθανώς εις την περιοχήν του Σουλίου ..."

- a) The mother tongue of Botsaris and his coworkers was the Greek ...

- b) It is also possible that the influence of the Greek was so heavy on the Albanian possibly spoken in the area of Souli, ..."

- ↑ Protopsaltes G. Emmanouel, The diary of captivity of Fotos Tzavellas 1792–1793), in “Mneme Souliou”, edited by the “Athens Society of the Friends of Souli”, 1973, vol. 2, pp. 213-225, in Greek. The text of the diary is in pp. 226-235.

- ↑ Protopsaltes G. Emmanouel, Souli, Souliotes, Bibliotheke Epirotikes Etaireias Athenon (B.H.E.A.), No 53, p. 7, Athens, 1984. In Greek.

- 1 2 Baltsiotis (2011). The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece.

Although the langue-vehiculaire of the area was Albanian, a much higher status was attributed to the Greek language, even among the Muslims themselves. Thus, during the late Ottoman era, besides the official Ottoman Turkish, Greek functioned as a second, semi-official language, accepted by the Ottoman Administration. This characteristic can be followed partly from public documents of the era. ... The lieutenant of the Greek Army Dimitrios (Takis) Botsaris, after a looting incident during the First Balkan War, pronounces an order that “from this time on every one who will dare to disturb any Christian property will be strictly punished” (see K.D. Sterghiopoulos…, op.cit., pp. 173-174). In pronouncing the order in this manner he left Muslim properties without protection. Botsaris, coming from Souli, was a direct descendant of the Botsaris’ family and was fluent in Albanian. He was appointed as lieutenant in charge of a Volunteers’ company consisting of persons originating from Epirus and fighting mostly in South Western Epirus.

- ↑ Fauriel Claude Charles , Chants populaires de la Grèce moderne, vol. 1, Didot, Paris, 1824, pp 284-302.

Sources

- Hart, Laurie Kain (Feb 1999), "Culture, Civilization, and Demarcation at the Northwest Borders of Greece", American Ethnologist, Blackwell Publishing, 26 (1): 196–220, doi:10.1525/ae.1999.26.1.196

- Roudometof, Victor; Robertson, Roland (2001), Nationalism, globalization, and orthodoxy: the social origins of ethnic conflict in the Balkans, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, ISBN 978-0-313-31949-5

- Davenport, R. A. (1837). The Life of Ali Pasha, of Zepeleni, Vizier of Epirus: Surnamed Aslan Or the Lion. Thomas Tegg and Son.

- Pouqueville, François (1813). Trav︠e︡ls in the Morea, Albania, and Other Parts of the Ottoman Empire: Comprehending a General Description of Those Countries; Their Productions; the Manners, Customs, and Commerce of the Inhabitants: a Comparison Between the Ancient and Present State of Greece: and an Historical and Geographical Description of the Ancient Epirus. Henry Colburn. pp. 121, 126, 352, 379, 382, 390–394.

- Skiotis, Dennis (1976). "The Greek Revolution: Ali Pasha's Last Gamble" (PDF). Hellenism and the First Greek War of Liberation (1821–1830): Continuity and Change. University of York, Faculty of Liberal Arts & Professional Studies: 97–109. Retrieved 16 November 2015.