Morea expedition

The Morea expedition (French: Expédition de Morée) is the name given in France to the land intervention of the French Army in the Peloponnese (at the time often still known by its medieval name, Morea) between 1828 and 1833, at the time of the Greek War of Independence.

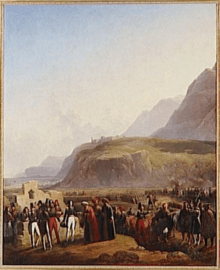

After the fall of Messolonghi, Western Europe decided to intervene in favour of revolutionary Greece. Their attitude toward the Ottoman Empire's Egyptian ally, Ibrahim Pasha, was especially critical; their primary objective was to elicit the evacuation of the occupied regions, the Peloponnese in particular. The intervention began when a Franco-Russo-British fleet was sent to the region, winning the Battle of Navarino in October 1827. In August 1828, a French expeditionary corps disembarked at Koroni in the southern Peloponnese. The soldiers were stationed on the peninsula until the evacuation of Egyptian troops in October, then taking control of the principal strongholds still held by Turkish troops. Although the bulk of the troops returned to France from the end of 1828, there was a French presence in the area until 1833.

As during Napoleon's Egyptian Campaign, when a Commission of Sciences and Arts had accompanied the military campaign, a Morea scientific expedition (Expédition scientifique de Morée.) accompanied the troops. Seventeen learned men represented different specialties (natural history and antiquities – archaeology, architecture and sculpture) made the voyage. Their work was of major importance in increasing knowledge about the country. As an example, the topographic maps they produced were excellent. More significantly, the measurements, drawings, profiles, plans and proposals for the theoretical restoration of Peloponnesian monuments, of Attica and of the Cyclades were, following James Stuart and Nicholas Revett's Antiquities of Athens, a new attempt to systematically and exhaustively catalogue ancient Greek ruins. The Morea expedition and its publications offered a near-complete description of the regions visited. They formed a scientific, aesthetic and human inventory that remained one of the best means, short of visiting them in person, to get to know the regions.

Context

Military and diplomatic context

In 1821, the Greeks revolted against centuries-long Ottoman rule. They won numerous victories early on and declared independence. However, the declaration contradicted the principles of the Congress of Vienna and of the Holy Alliance, which imposed a European equilibrium of the status quo, outlawing any change. In contrast to what happened elsewhere in Europe, the Holy Alliance did not intervene to stop the liberal Greek insurgents.

The liberal and national uprising displeased the Austria of Metternich, the principal political architect of the Holy Alliance. However, Russia, another reactionary gendarme of Europe, looked favorably on the insurrection due to its Orthodox religious solidarity and its geostrategic interest (control of the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus). France, another active member of the Holy Alliance, had just intervened in Spain against liberals at Trocadero (1823) but held an ambiguous position: Paris saw the liberal Greeks first and foremost as Christians, and their uprising against the Muslim Ottomans had undertones of a new crusade. Great Britain, a liberal country, was interested in the regional situation primarily because it lay on the route to India and London wished to exercise a form of control there. For all of Europe, Greece represented the cradle of Western civilisation and of art since antiquity.

The Greek victories had been short-lived. The Sultan had called to his aid his Egyptian vassal Muhammad Ali, who had dispatched his son Ibrahim Pasha to Greece with a fleet and 8,000 men, later adding a further 25,000 troops.[1] Ibrahim’s intervention proved decisive: the Peloponnese had been reconquered in 1825; the gateway town of Messolonghi had fallen in 1826; Athens had been taken in 1827. All that Greek nationalists still held was Nafplion, Hydra, Mani and Aegina.

A strong current of philhellenism developed in Western Europe. Thus it was decided to intervene in favour of Greece, the cradle of civilisation and a Christian vanguard in the Orient whose strategic location was clear. By the Treaty of London of July 1827,[2] France, Russia and the United Kingdom recognised the autonomy of Greece, which remained a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. The three powers agreed to a limited intervention in order to convince the Porte to accept the terms of the convention. A plan to send a naval expedition as a show of force was proposed and adopted. A joint Russian, French and British fleet was sent to exercise diplomatic pressure against Constantinople. The Battle of Navarino (October 1827), fought after a chance encounter, resulted in the destruction of the Turkish-Egyptian fleet.

In 1828, Ibrahim Pasha thus found himself in a difficult situation: he had just suffered a defeat at Navarino; the joint fleet exercised a blockade which prevented him from receiving reinforcements and supplies; his Albanian troops, whom he could no longer pay, had returned to their country under the protection of Theodoros Kolokotronis’ Greek troops. On August 6, 1828, a convention had been signed at Alexandria between the viceroy of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, and the British admiral Edward Codrington. Ibrahim Pasha had to evacuate his Egyptian troops and leave the Peloponnese to the few Turkish troops (estimated at 1200 men) remaining there. However, Ibrahim Pasha refused to honor the agreement that had been reached, continuing to control various Greek regions: Messenia, Navarino, Patras and several other strongholds. He had also ordered the systematic destruction of Tripoli.[3]

In addition, the French government of Charles X was beginning to have doubts about its Greek policy.[4] Ibrahim Pasha himself noted this ambiguity when he met General Maison in September: “Why was France, after enslaving men in Spain in 1823, now coming to Greece to make men free?”[5] Eventually a liberal agitation, pro-Greek and inspired by what was then happening in that country, began to develop in France. The longer France waited, the more delicate her position vis-à-vis Metternich became. The ultra-royalist government thus decided to accelerate events. A land expedition was proposed to Great Britain, which refused to intervene directly. Meanwhile, Russia had declared war against the Ottoman Empire and its military victories were unsettling for London, which did not wish to see the Tsarist empire extend too far south. Thus Great Britain did not oppose an intervention by France alone.[6]

Intellectual context

Enlightenment philosophy had developed Western Europeans’ interest in Greece, or rather in an idealised Ancient Greece, the linchpin of Antiquity, as it was perceived and taught. The Enlightenment philosophers, for whom the notions of Nature and Reason were so important, believed that these had been the fundamental values of Classical Athens. The Ancient Greek democracies, and above all Athens, became models to emulate. There they searched for answers to the political and philosophical problems of their time. Works such as those of Abbé Barthélemy, Voyage du Jeune Anacharsis (1788), served to fix definitively the image that Europe had of the Aegean.

The theories and system of interpreting ancient art devised by Johann Joachim Winckelmann influenced European tastes for decades. His major work, History of Ancient Art, was published in 1764 and translated into French in 1766 (the English translation came later, in 1881). In this major work Winckelmann initiated the tradition of dividing ancient art into periods, classifying the works chronologically and stylistically.[7]

The views of Winckelmann on art encompassed the entirety of civilisation. He drew a parallel between a civilisation's general level of development and the evolution of its art. He interpreted this artistic evolution the same way that his contemporaries saw the life cycle of a civilisation, in terms of progress, apogee and then decline.[8] For him, Greek art had been the pinnacle of artistic achievement, culminating with Phidias. Further, Winckelmann believed that the most beautiful works of Greek art had been produced under ideal geographic, political and religious circumstances. This frame of thought long dominated intellectual life in Europe. He classified Greek art into four periods: Ancient (archaic period), Sublime (Phidias), Beautiful (Praxiteles) and Decadent (Roman period).

Winckelmann’s theories on the evolution of art culminated in the Sublime period of Greek art, which had been conceived during a period of complete political and religious liberty. The theories idealised Ancient Greece and increased people’s desire to travel to contemporary Greece. It was seductive to believe, as he did, that 'good taste' was born beneath the Greek sky. He convinced 18th-century Europe that life in Ancient Greece was pure, simple and moral, and that classical Hellas was the source from which artists should draw ideas of “noble simplicity and calm grandeur”.[9] Greece became the “motherland of the arts” and “the teacher of taste”.[10]

The French government had planned the Morea expedition in the same spirit as those of James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, whose work it wished to complete. The semi-scientific expeditions commissioned and financed by the Society of Dilettanti remained a benchmark: these represented the first attempts to rediscover Ancient Greece. The first, that of Stuart and Revett to Athens and the islands, took place in 1751–1753, and resulted in The Antiquities of Athens, mined by architects and designers for a refined "Grecian" neoclassicism. The expedition of Revett, Richard Chandler and William Pars to Asia Minor took place between 1764 and 1766. Finally, the “work” of Lord Elgin on the Parthenon at the beginning of the 19th century had sparked further longing for Greece: it now seemed possible to build vast collections of ancient art in Western Europe.

Military expedition

Preparation

The Chamber of Deputies authorised a loan of 80 million gold francs to allow the government to meet its obligations.[11] An expeditionary corps of 13,000–15,000 men[12] commanded by Lieutenant-General Nicolas Joseph Maison was formed. It was composed of three brigades commanded by the maréchaux de camp Tiburce Sébastiani (brother of the Corsican soldier-diplomat Horace François Bastien Sébastiani de La Porta), Philippe Higonet, and Virgile Schneider. The Chief of the General Staff was General Antoine Simon Durrieu.[13]

The expeditionary corps was made up of nine infantry regiments:[14]

- 1st brigade: 8th Line Infantry Regiment, 16th Line Infantry Regiment, 27th Light Infantry Regiment

- 2nd brigade: 35th Line Infantry Regiment, 46th Line Infantry Regiment, 58th Line Infantry Regiment

- 3rd brigade: 29th Line Infantry Regiment, 42nd Line Infantry Regiment, 54th Line Infantry Regiment

Also departing were the 3rd Chasseur Regiment (commanded by Colonel Paul-Eugène de Faudoas-Barbazan), four companies of artillery (with equipment for campaigns, sieges, and mountains) of the 3rd and 8th Artillery Regiments, and two companies of military engineers (sappers and miners).[15]

A transport fleet protected by warships was organised; sixty ships sailed in all. Equipment, victuals, munitions and 1,300 horses had to be brought over, as well as arms, munitions and money for the Greek provisional government of John Capodistria.[16] France wished to support free Greece as it came into being by helping it activate its army, with the aim of gaining influence in the region.

The first brigade left Toulon on August 17; the second, two days later; and the third on September 1. The general in command, Nicolas Joseph Maison, was with the first brigade, aboard the ship of the line Ville de Marseille. The first convoy was composed of merchant ships and apart from the Ville de Marseille, it included the frigates Amphitrite, Bellone and Cybèle. The second convoy was escorted by ship of the line Duquesne and the frigates Iphigénie and Armide.[17]

Operations in the Peloponnese

Landing

On August 29, the fleet transporting the two first brigades arrived in Navarino bay, where the joint Franco-Russo-British squadron was berthed. The Egyptian army was concentrated between Navarino and Methoni. Thus, the landing was risky. The fleet sailed toward the Gulf of Koroni protected by a fortress held by the Ottomans. The expeditionary corps began to disembark without meeting any opposition on the evening of August 29, finishing on the morning of August 30. A proclamation by governor Capodistria had informed the Greek population of the imminent arrival of a French expedition. The locals rushed up before the troops as soon as they set foot on Greek soil and offered them food.[18]

The French pitched camp in the plain of Koroni, near Petalidi, on the site of the ancient Coronea. The third brigade, which had borne up against a storm and lost three ships, managed to land at Koroni on September 16.[19]

Departure of the Egyptian Army

Ibrahim Pasha used a number of pretexts to delay the evacuation: problems with food supply or transport, or unforeseen difficulties in the strongholds’ handover. The French officers had difficulties in maintaining the fighting zeal of their soldiers, who for example had become excited at the (false) news that an imminent march on Athens would take place.[20] This impatience on the part of the French troops was perhaps decisive in convincing the Egyptian commander to respect his obligations. Moreover, French soldiers were beginning to suffer from autumn rains which drenched their tent camp, increasing the likelihood of fever and especially of dysentery. On September 24, Louis-Eugène Cavaignac wrote that thirty men of 400 in his company of military engineers were affected by fever.[21] General Maison wished to be able to set up his men in the fortresses’ barracks.[22] On September 7, Ibrahim Pasha accepted to evacuate his troops as of September 9. The agreement reached with General Maison provided that the Egyptians would leave with their arms, baggage and horses, but without any Greek slave or prisoner. As the Egyptian fleet could not evacuate the entire army in one go, supplies were authorised for the troops who remained on land; these men had just undergone a lengthy blockade.[19] A first Egyptian division, 5,500 men and 27 ships, set sail on September 16, escorted by three ships from the joint fleet (two English ones and the French frigate Sirène).

The last Egyptian transport sailed away on October 5, taking Ibrahim Pasha. Of the 40,000 men he had brought from Egypt, he was taking back barely 20,000.[23] A few Ottoman soldiers remained in order to hold the different strongholds of the Peloponnese. The next mission of the French troops was to “give security” to these and hand them back to independent Greece.

Strongholds taken

On October 6, General Maison ordered General Higonet to march on Navarino. He left with the 16th Infantry Regiment, which included artillery and military engineers. Thus, Navarino’s seacoast was put under siege by Admiral Henri de Rigny’s fleet and the land siege was undertaken by General Higonet’s soldiers. The Turkish commander of the fort refused to surrender:

“The Porte is at war with neither the French nor the English; we will commit no hostile act, but we will not surrender the fort.”[19]

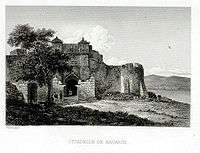

Hence, the sappers received an order to open a breach in the walls. General Higonet entered the fortress, held by 250 men who surrendered with sixty cannons and 800,000 rounds of ammunition.[19] The French troops moved in intending to remain for some time, building up Navarino’s fortifications, rebuilding its houses and setting up a hospital and various features of local administration.

On October 7, the 35th Line Infantry Regiment, commanded by General Durrieu, accompanied by artillery and by military engineers, appeared before Methoni, defended by 1,078 men and a hundred cannons, and which had food supplies for six months.[19] Two ships of the line, the Breslaw (Captain Maillard) and HMS Wellesley (Captain Frederick Lewis Maitland) blocked the port and threatened the fortress with their cannons. The fort’s commanders, the Turk Hassan Pasha and the Egyptian Ahmed Bey, made the same reply as had the commander of Navarino. Methoni’s fortifications were in a better state than those of Navarino. Thus the sappers focused on opening the city gate. The city’s garrison did not defend it. The commanders of the fort explained that they could not surrender it without disobeying the Sultan’s orders, but also recognised that it was impossible for them to resist. Thus the fort had to be taken, at least symbolically, by force.[19]

It was more difficult to take Koroni. General Sébastiani showed up there on October 7 with a party from his brigade. The fort commander’s response was similar to those given at Navarino and Methoni. Sébastiani sent his sappers, who were pushed back by rocks thrown from atop the walls. A dozen men were wounded, among them Cavaignac and, more seriously, a captain, a sergeant and three sappers.[24] The other French soldiers felt insulted and their general had great difficulty in preventing them from opening fire and taking the stronghold by force. The Amphitrite, the Breslaw and the Wellesley came to the assistance of the ground troops. The threat they posed led the Ottoman commander to surrender. On October 9, the French entered Koroni and seized 80 cannons and guns, along with numerous victuals and munitions.[19]

Patras had been controlled by Ibrahim Pasha since the evacuation of the Peloponnese. The third brigade had been sent by sea to take the city, located in the north-western part of the peninsula. It landed on October 4. General Schneider gave Hadji Abdullah, Pasha of Patras and of the “Castle of the Morea”, twenty-four hours to hand over the fort. On October 5, when the ultimatum expired, three columns marched on the city and the artillery was deployed. The Pasha immediately signed the capitulation of Patras and of the “Castle of the Morea”.[19] However, the aghas who commanded the latter refused to obey their pasha, whom they considered a traitor, and announced that they would rather die in the ruins of their fortress than surrender.

Siege of the "Morea Castle"

The "Castle of the Morea" guarded the entry to the Gulf of Corinth, near Rion. Bayezid II had built it in 1499.[25]

General Schneider negotiated with the aghas, who persisted in their refusal to surrender. A siege was begun from in front of the fortress and fourteen marine and field guns, placed a little over 400 meters away, reduced the artillery of those under siege to silence.[26] Admiral de Rigny had General Maison put all his artillery and sappers on board. By land Maison sent two infantry regiments and the 3rd Light Cavalry Regiment. Reinforcements arrived on October 23. New batteries nicknamed “for breaching” (de brèche) were installed. These received the names of Charles X, George IV, the Duke of Angoulême, the Duke of Bordeaux and “Marine”.[26] A party from the British fleet and HMS Blonde under Captain Edmund Lyons came to add their cannons.

On October 30, the batteries opened fire. In four hours, a breach was largely opened in the ramparts. Then, an emissary came out with a white flag to negotiate the terms of the fort’s surrender. General Maison replied that the terms had been negotiated at the beginning of the month at Patras. He added that he did not trust a group of besieged men who had not respected a first agreement to respect a second one. He gave the garrison half an hour to evacuate the fort, without arms or baggage.[26] The aghas submitted. However, the fortress’ resistance had cost 25 men, killed or wounded in the French expedition.[27]

The French in the Peloponnese

On November 5, 1828, the last “non-Greeks” (Turks, Egyptians or Muslims generally) left the Morea. 2,500 Turks and their families were placed aboard French vessels headed for Smyrna.[26]

The French and British ambassadors had set themselves up at Poros and invited Constantinople to send a diplomat there so as to pursue negotiations over the status of Greece. The Porte persisted in refusing to participate in conferences. Hence, the French suggested continuing military operations and extending them into Attica and Euboea. The British opposed this plan. Thus it was left to the Greeks to drive out the Ottomans from these territories, with the understanding that the French army would only intervene if the Greeks found themselves in trouble.[23]

Gradually, the Morea was evacuated of troops. The Schneider brigade, of which Cavaignac was a member, boarded ship in the first days of April 1829. General Maison left on May 22, 1829.[28] Only one brigade remained in the Peloponnese. Fresh troops came from France to relieve the soldiers present in Greece: thus the 57th Line Infantry Regiment landed at Navarino on July 25, 1830.[29] France did not withdraw its troops for good until after King Otto arrived in Greece in January 1833.

The French troops, commanded by General Charles Louis Joseph Olivier Guéhéneuc, did not remain idle during these nearly five years. Fortifications were raised, like those at Navarino.[30] Bridges were constructed, such as those over the Pamissos River between Kalamata and Methoni. The Methoni–Navarino road was built, and improvements were made to Peloponnesian towns (barracks, bridges, gardens, etc.).[26]

Military results of the expedition

The Ottoman Empire could no longer depend on Egyptian troops to hold Greece. The strategic situation now resembled that existing before 1825 and the landing of Ibrahim Pasha. Then, the Greek insurgents had triumphed on all fronts.

After the Morea military expedition, the Greeks only had to face the Turkish troops in Central Greece. Livadeia, gateway to Boeotia, was conquered at the beginning of November 1828. A counterattack by Mahmud Pasha from Euboea was repulsed in January 1829. In April, Naupaktos was restored to the Greeks; in May, Augustinos Kapodistrias recaptured the symbolic town of Messolonghi.[31] However, it took the military victory of Russia in the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29 and the Treaty of Adrianople before the independence of Greece was recognised.

The Greek territories that had been liberated by September 1829, a year after the Morea military expedition—the Peloponnese and central Greece—were those which would form independent Greece after 1832.

Scientific expedition

The Morea expedition was the second of the great military-scientific expeditions led by France in the first half of the 19th century. The first, used as a benchmark, had been the Egyptian one, starting in 1798; the last took place in Algeria from 1839. All three took place at the initiative of the French government and were placed under the guidance of a particular ministry (Foreign relations for Egypt, Interior for the Morea and War for Algeria).[32] The great scientific institutions recruited learned men (both civilians and from the military) and specified their missions, but in situ work took place in close co-operation with the army.

The Commission of Sciences and Arts from Napoleon’s Egyptian expedition, and especially the publications that followed, had become a model. As Greece was the other important “ancient” region considered as lying at the origin of Western civilisation (one of the philhellenes’ principal arguments), it was decided to “take advantage of the presence of our soldiers who were occupying the Morea to send a learned commission. It did not have to equal that attached to the glory of Napoleon […] It did however need to render eminent services to the arts and sciences.”[33]

In Egypt and Algeria, scientific work took place under the army’s protection. In the Morea, most troops were departing when exploration had barely begun. The army was content to provide logistical support: “tents, stakes, tools, liquid containers, large pots and sacks; in a word, everything that could be found for us to use in the army’s storehouses.”[34]

The members of the scientific expedition landed at Navarino on March 3, 1829, after 21 days at sea.[35]

Physical sciences section

This section included several sciences: botany (Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent, Louis Despreaux Saint-Sauveur and Antoine Vincent Pector), geography, geology (Pierre Théodore Virlet d’Aoust and Émile Puillon Boblaye) and zoology. The government insisted that a landscape artist also be sent, as Minister of the Interior Martignac had asked for one so as not to restrict the observations “to flies and herbs, but to extend them to places and people.”[36]

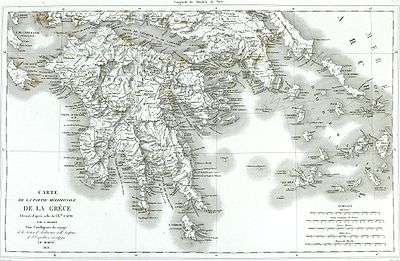

Geography

One of the first objectives fixed by the French government had been to draw precise maps of the Peloponnese, with a scientific purpose, but also for economic and military reasons. The Minister of War, the Vicomte de Caux, had written to General Maison on January 6, 1829:

“All the maps of Greece are very imperfect and were drawn up based on more or less inaccurate templates; it is thus essential to fix them. Not only will geography be enriched by this research, but we will in the process support France’s commercial interests by making her relations easier, and it will above all be useful for our ground and naval forces, who may find themselves involved in this part of Europe.”[37]

In two years, a very precise map, drawn on six sheets at a 1/200,000 scale, was produced. In March 1829, a base of 3,500 meters had been traced in the Argolis, from one angle at the ruins of Tiryns to an angle of a house in ruins in the village of Aria.[38] This was intended to serve as a point of departure in all the triangulation operations for topographic and geodesic readings in the Peloponnese. Pierre Peytier and Puillon-Boblaye proceeded to perform numerous verifications on the base and on the rulers used. The margin of error was thus reduced to 1 meter for every 15 kilometers.[39] The longitude and latitude of the base point at Tiryns were read and checked, so that again the margin of error was reduced as far as possible to an estimated 0.2 seconds.[40] 134 geodesic stations were set up on the peninsula’s mountains, as well as on Aegina, Hydra and Nafplion. Thus, equilateral triangles whose sides measured about 20 km were drawn. The angles were measured with theodolites by Gambey.[41]

The geographers suffered from fever—Bory de Saint-Vincent’s team as much as that of Puillon-Boblaye:

“The horrible heat that beset us in July placed, for the rest, the entire topographic brigade in disarray. These gentlemen, having worked in the sun, have nearly all taken ill and eight days ago, we grieved to see M. Dechièvre die at Napoli eight days ago.”[42] (Bory de Saint-Vincent)

“Of twelve officers employed in the geodesic service, two are dead and all have been sick. Besides them, we have lost two sappers and a household servant.”[43] (Puillon-Boblaye)

Botany and zoology

Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent led the scientific expedition. Additionally, he made detailed botanical studies. He gathered a multitude of specimens: Flore de Morée (1832) lists 1,550 plants, of which 33 were orchids and 91 were grasses (just 42 species had not yet been described); Nouvelle Flore du Péloponnèse et des Cyclades (1838) described 1,821 species.[44] In Morea, Bory de Saint-Vincent was content to collect plants. He proceeded to classify, identify and describe them upon his return to France. Then he was aided, not by his collaborators from Greece, but by Louis Athanase Chaubard, Jean-Baptiste Fauché and Adolphe-Théodore Brongniart.[45] Similarly, the naturalists Étienne and Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire helped edit the expedition’s scientific works.

As the gathering process went along, they sent the plants, as well as birds and fish, to France.[46]

The Morea expedition confirmed that the golden jackal existed in Greece. Although earlier travel narratives had mentioned its presence, these were not considered trustworthy. Moreover, the subspecies seen and described by the French (named Canis aureus moreotica) was endemic to the region. Bory de Saint-Vincent brought back pelts and a skull.[47]

Fine arts section

This section was formed by the Institut de France, which designated the architect Guillaume-Abel Blouet as its head. The Institut sent Amable Ravoisié, Pierre Achille Poirot, Frédéric de Gournay and Pierre Félix Trezel as his assistants.

The architect Jean-Nicolas Huyot gave very precise instructions to this section. Of wide-ranging experience formed in Asia Minor and Egypt and under the influence of engineers, he asked them to keep an authentic diary of their excavations where precision measurements read off watches and compasses should be written down, to draw a map of the region they travelled, and to describe the layout of the terrain.[48]

Itineraries

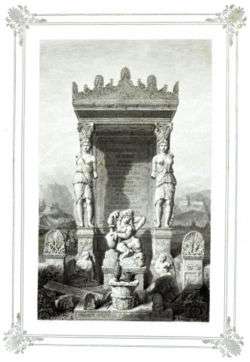

The publication of works on archaeology and art followed the same pattern as with works on physical and natural sciences: that of an itinerary with descriptions of the roads travelled, noteworthy monuments along these routes and descriptions of their destinations. Hence, volume I of Expédition de Morée. Section des Beaux Arts describes Navarino (pp. 1–7[49]) with six pages of plates (fountains, churches, the fortress of Navarino and the palace of Nestor at Pylos[50]); then on pages 9–10, the Navarino-Methoni road[51] is detailed with four pages of plates (a church in ruins and its frescoes, but also bucolic landscapes reminding the reader that the scene is not so far from Arcadia);[52] and finally three pages on Methoni[53] and four pages of plates.[54] The bucolic landscapes were rather close to the “norm” that Hubert Robert had proposed for depictions of Greece.

The presence of troops from the expeditionary corps was important, alternating with that of Greek shepherds:

“(…) their generous hospitality and simple and innocent mores reminded us of the beautiful period of pastoral life which fiction calls the Golden age, and seemed to present to us as real people the characters of Theocritus’ and Virgil’s eclogues.”[55]

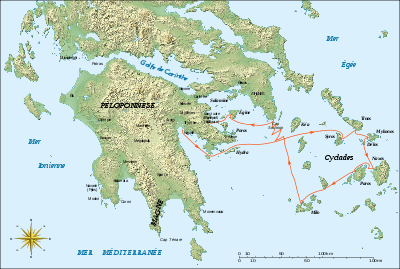

The archaeological expedition travelled through Navarino (Pylos), Methoni, Koroni, Messene and Olympia (described in the publication’s first volume); Bassae, Megalopolis, Sparta, Mantineia, Argos, Mycenae, Tiryns and Nafplion (subjects of the second volume); the Cyclades (Syros, Kea, Mykonos, Delos, Naxos and Milos), Sounion, Aegina, Epidaurus, Troezen, Nemea, Corinth, Sicyon, Patras, Elis, Kalamata, the Mani Peninsula, Cape Matapan, Monemvasia, Athens, Salamis Island and Eleusina (covered in volume III).

Edgar Quinet had left with the rest of the expedition. However, from the time he arrived in Greece, he kept apart from his companions, as did another member of his section, the Lyon sculptor Jean-Baptiste Vietty. The two travelled through the Peloponnese separately and Quinet visited Piraeus on April 21, 1829, thence reaching Athens. He saw the Cyclades in May, starting with Syros. Having taken ill, he returned to France on June 5, and his Grèce moderne et ses rapports avec l’Antiquité appeared in September 1831.[56] Vietty pursued his research in Greece until August 1831, long after the expedition had returned to France at the end of 1829.[57]

Ways of exploration

The artistic and archaeological exploration of the Peloponnese unfolded in the manner in which archaeological research was then conducted in Greece. The first step always involved an attempt to make an on-site check (a form of autopsy in the manner of Herodotus) against the texts of ancient authors like Homer, Pausanias or Strabo. Thus, at Navarino, the location of Nestor’s palace was determined from Homer and the adjectives “inaccessible” and “sandy”.[58] At Methoni, “the ancient remains of the port of which the description matches perfectly with that of Pausanias are enough to determine with certainty the location of the ancient town.”[59]

Having explored Navarino, Methoni and Koroni, the members of the expedition returned to Messene, where they spent a month starting on April 10.[60]

Olympia

The expedition spent six weeks, starting on May 10, 1829,[61] in Olympia. Abel Blouet and Dubois undertook the first excavations there. They were accompanied by the painters Poirot, Trezel and Duval. The archaeological advice of Huyot was followed:

“Following the instructions which had been given to him by the commission of the Institute, this antiquarian (Dubois) had begun the excavations of which the result had been the discovery of the first bases of the two columns of the pronaos and several fragments of sculpture.”[62]

The site was divided into squares and excavations were undertaken in straight lines: archaeology was becoming rationalised, and it was in this way that the location of the temple of Zeus was determined.[63] The simple chase after treasure was beginning to be abandoned.

The fundamental contribution of the Morea scientific expedition was in effect its quasi-disinterest in pillage and treasure hunting. Blouet refused to perform excavations that risked damaging the monuments, and banned the mutilation of statues with the intent of taking a piece separated from the rest of the statue without regard.[64] It is perhaps for this reason that the three metopes of the temple of Zeus discovered at Olympia were brought back in their entirety. In any case, this willingness to protect the integrity of monuments undoubtedly represented an epistemological progress.

Byzantine Greece

The French did not limit their interest to Antiquity; they also described and drew Byzantine monuments. Quite often, and until then for the travellers as well, only Ancient Greece mattered; medieval and modern Greece were ignored. Blouet, in his Expédition de Morée, gave very precise descriptions of the churches he saw. For instance, plate 9 (I, II and III) of volume I deals with:

“Layout, section and perspective view of one of the two small churches of the village of Osphino, situated on the slope of the mountain to the left of the Navarino-Methoni road; (…); its interior, decorated with paintings and frescoes, is divided into two parts by a wall that forms a small closed sanctuary in the back in which the priest stands to officiate.”[65]

Foundation of the French School at Athens

The results obtained by the Morea scientific expedition underscored the need to create a permanent, stable structure that would allow its work to continue. From 1846, it was possible to “systematically and permanently continue the work so gloriously and so happily begun by the Morea scientific expedition”[66] due to the creation on rue Didot, at the foot of Mount Lycabettus, of a French scientific institution, in the form of the French School at Athens.

Publications

- Abel Blouet and Amable Ravoisié, Expédition scientifique de Morée, ordonnée par le Gouvernement Francais. Architecture, Sculptures, Inscriptions et Vues du Péloponèse, des Cyclades et de l’Attique., Firmin Didot, 1831. (3 volumes)

- J. B. Bory de Saint-Vincent, Relation du voyage de la Commission scientifique de Morée dans le Péloponnèse, les Cyclades et l’Attique., Levrault, 1836–1838. 2 volumes and an atlas.

- J. B. Bory de Saint-Vincent (and collaborators), Expédition scientifique de Morée. Section des sciences physiques., volume II Géographie et géologie., 1834.

- J. B. Bory de Saint-Vincent (and collaborators), Expédition scientifique de Morée. Section des sciences physiques., volume III Botanique, also called Flore de Morée., 1832.

- J. B. Bory de Saint-Vincent (and Louis Athanase Chaubard), Nouvelle Flore du Péloponnèse et des Cyclades., 1838 (revised and expanded edition of 1832’s Flore de Morée.).

- E. Puillon-Boblaye, Recherches géographiques sur les ruines de Morée., Levrault, 1836.

See also

Members of the military expedition General Maison

Troops involved

|

Members of the scientific expedition and related individuals Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent

Notea : It is very difficult to find a complete and exhaustive list of the members of the scientific expedition. Often, it is necessary to make conjectures based on incomplete information. Names marked are those found in various sources, but still in doubt. |

External links

- (French) Abel Blouet, Expédition scientifique de Morée : Architecture, Sculptures, Inscriptions (site navigation in German)

- (French) Bory de Saint-Vincent, Expédition scientifique de Morée : Section des sciences physiques. Botanique, v. III., 2nd part

- (French) Bory de Saint-Vincent, Expédition scientifique de Morée : Section des sciences physiques. Atlas, 1831–1835. (botanical plates)

- (French) Jean Schmitz, Territorialisation du savoir et invention de la Méditerranée, in Cahiers d'Études africaines, n°165 (2002)

- (French) “Notice sur les opérations géodésiques exécutées en Morée, en 1829 et 1830, par MM. Peytier, Puillon-Boblay et Servier ; suivie d’un catalogue des positions géographiques des principaux points déterminés par ces opérations.”, in Bulletin de la Société de géographie, v. 19 n°117–122 (January – June 1833)

- (English) Witmore, C.L. 2005: “The Expedition scientifique de Moree and a map of the Peloponnesus.” Dissertation on the Metamedia site at Stanford University

Notes

- ↑ An Index of events in the military history of the Greek nation., Hellenic Army General Staff, Army History Directorate, Athens, 1998, pp. 51 and 54. ISBN 960-7897-27-7

- ↑ The text on Gallica

- ↑ M. Brunet de Presle and Alexandre Blanchet, La Grèce, p. 555.

- ↑ de Presle, p. 556.

- ↑ Arch de Vaulabelle, Histoire des deux Restaurations, vol. 7, p. 472

- ↑ Arch. de Vaulabelle, Histoire des deux Restaurations, vol. 7, p. 649.

- ↑ Alain Schnapp, La Conquête du passé. Aux origines de l'archéologie., Editions Carré, Paris, 1993. p. 258.

- ↑ Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique., Yale University Press, 1981, p. 104.

- ↑ Cited by Roland and Françoise Etienne, La Grèce antique., Gallimard, 1990, p. 60-61.

- ↑ Roland and Françoise Etienne, La Grèce antique., Gallimard, 1990, p. 44-45.

- ↑ Antoine Calmon, Histoire parlementaire des finances de la Restauration., Michel Lévy, 1868–1870, vol. 2, p. 313.

- ↑ Sources differ on this point. Brunet de Presle and A. Blanchet, La Grèce give 13,000 men; A. Hugo, France militaire has 14,000; Arch. de Vaulabelle, Histoire des deux Restaurations, 14,062. The Revue des Deux Mondes (vol. 141, 1897) gives 480 officers and 8,489 regular troops plus 17 officers and 391 soldiers in the military engineers. General histories estimate 15,000.

- ↑ A. Hugo, France militaire. Histoire des armées françaises., vol. 5, p. 316

- ↑ Sources differ. A. Hugo in France militaire suggests the 54th and the 58th Infantry Regiments, whereas Arch. de Vaulabelle in Histoire des deux Restaurations names the 56th and 58th Infantry Regiments and L’Historique du 57e Régiment d’Infanterie says that this regiment left for the Morea (in fact, it formed part of the replacements that arrived in 1830). The composition of the brigades is that given by A. Hugon, as it is the most precise.

- ↑ A. Hugo, France militaire. gives the 3rd Military Engineers Regiment while Vaulabelle’s Histoire des deux Restaurations gives the 2nd Military Engineers Regiment.

- ↑ A. Hugo, p. 316

- ↑ Vice-Admiral Jurien de la Gravière, « Station du Levant. L’Expédition de Morée », in Revue des deux Mondes, 1874, p. 867.

- ↑ Arch. de Vaulabelle, p.471.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A. Hugo, France militaire, vol. 5, p. 317

- ↑ Abel Blouet, Expédition scientifique de Morée., p. xxi.

- ↑ Letter to his mother in Revue des deux Mondes., vol. 141, 1897, p. 51.

- ↑ Arch. de Vaulabelle, p. 471.

- 1 2 M. Brunet de Presle and Alexandre Blanchet, p. 556.

- ↑ Letter of Cavaignac to his mother, October 12, 1828, in Revue des deux Mondes., p. 55.

- ↑ Robin Barber, Blue Guide. Greece., Black, London, 1987, p.392. ISBN 0-393-30372-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 A. Hugo, France militaire, vol. 5, p. 319

- ↑ M. Brunet de Presle and Alexandre Blanchet, p. 556.; A. Hugo, p. 319; and Arch de Vaulabelle, p. 474.

- ↑ Letter of Eugène Cavaignac to his mother, March 30, 1829, in Revue des deux Mondes., p. 69.

- ↑ Capitaine Berthemet, Historique du 57e régiment d'infanterie., Bordeaux, 1901, chapter 9. The regiment remained until 1833.

- ↑ "The city of Navarino (...) was handed over in 1829 to the French, whose army occupies it today. Part of the garrison is working to re-establish the citadel and the fortifications that surround it", in Abel Blouet, Expédition de Morée. Section des Beaux-Arts., vol. 1, p. 2.

- ↑ An Index of Events in the military History of the Greek Nation, p. 65-67.

- ↑ Bernard Lepetit, “Missions scientifiques et expéditions militaires : remarques sur leurs modalités d’articulation.”, in L’Invention scientifique de la Méditerranée., p. 97.

- ↑ A. Blouet, Expédition de Morée., p. xxii.

- ↑ Bory de Saint-Vincent, Relation du voyage de la Commission scientifique de Morée., vol 1, p. 114, in Bernard Lepetit, cited article, p. 100.

- ↑ Abel Blouet, Expédition scientifique de Morée., vol. 1, p. 1.

- ↑ Serge Briffaud, “L’Expédition scientifique de Morée et le paysage méditerranéen.” in L’invention scientifique de la Méditerranée, p.293.

- ↑ Bory de Saint-Vincent, Expédition scientifique de Morée. Section des sciences physiques., vol. II Géographie et géologie., p. 18. in Bernard Lepetit, cited article, p. 109.

- ↑ ”Notice sur les opérations géodésiques exécutées en Morée, en 1829 et 1830, par MM. Peytier, Puillon-Boblaye et Servier” in Bulletin de la Société de géographie, vol. 19, nr. 117-122, January – June 1833, p. 91.

- ↑ ”Notice…”, Peytier et al., p. 95.

- ↑ ”Notice…”, Peytier et al., p. 98.

- ↑ ”Notice…”, Peytier et al., p. 89.

- ↑ Bory de Saint-Vincent, Letter of August 4, 1829, in Bulletin de la Société de Géographie., vol. 12, nr. 75-80, July – December 1829., p. 122-123.

- ↑ Puillon-Boblaye, Letter of August 23, 1829, in Bulletin de la Société de Géographie., vol. 12, nr. 75-80, July – December 1829., p. 124.

- ↑ Jean-Marc Drouin, “Bory de Saint-Vincent et la géographie botanique.” in L’invention scientifique de la Méditerranée, p. 144.

- ↑ Drouin, p. 145.

- ↑ Nouvelles annales des voyages, de la géographie et de l’histoire ou Recueil des relations originales inédites, July – August – September 1829, p. 378.

- ↑ Nouvelles annales des voyages, de la géographie et de l’histoire ou Recueil des relations originales inédites, January – February – March 1837, p. 354-355.

- ↑ Bernard Lepetit, cited article, p. 112.

- ↑ Expédition de Morée. Section des Beaux Arts., vol. 1, Navarino, pages 1 to 7

- ↑ Expédition de Morée. Section des Beaux Arts., vol. 1, six pages of plates on Navarino

- ↑ Expédition de Morée. Section des Beaux Arts., vol. 1, Navarin-Methoni road, pages 9 and 10

- ↑ Expédition de Morée. Section des Beaux Arts., vol. 1, four pages of plates on the Navarino-Methoni road

- ↑ Expédition de Morée. Section des Beaux Arts., vol. 1, Methoni

- ↑ Expédition de Morée. Section des Beaux Arts., vol. 1, four pages of plates. Methoni

- ↑ Abel Blouet, Expédition de Morée., tome 1, p. 25 à propos de Messène.

- ↑ Hervé Duchêne, Le Voyage en Grèce., Bouquins, Robert Laffont, 2003, ISBN 2-221-08460-8, p. 557.

- ↑ Stéphane Gioanni, « Jean-Baptiste Vietty et l'Expédition de Morée (1829). A propos de deux manuscrits retrouvés », in Journal des Savants, 2008. 2, p. 383-429.

- ↑ Abel Blouet, Expédition de Morée. v. I, p. 6.

- ↑ A. Blouet, Expédition de Morée., v. I, p. 12.

- ↑ "During the month that we spent at Messene, I ordered some rather considerable excavations, the results of which were not without importance for our work". A Blouet, Expédition de Morée., v. I, p. 12. The following pages describe the stadium and the ancient monuments in detail.

- ↑ Nouvelles annales des voyages, de la géographie et de l’histoire ou Recueil des relations originales inédites, 1829, p. 378.

- ↑ Abel Blouet, Expédition de Morée., vol. 1, p. 61.

- ↑ Map of the location of the temple of Zeus at Olympia

- ↑ Olga Polychronopoulou, Archéologues sur les pas d’Homère., p. 33.

- ↑ Abel Blouet, Expédition de Morée., tome 1, p. 10.

- ↑ M. Cavvadias, General Ephor of Antiquities, “Discours pour le cinquantenaire de l'Ecole Française d'Athènes”, Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique., XXII, 1899, p. LVIII.

References

- Marie-Noëlle Bourguet, Bernard Lepetit, Daniel Nordman, Maroula Sinarellis, L’Invention scientifique de la Méditerrannée. Égypte, Morée, Algérie., Éditions de l’EHESS, 1998. ISBN 2-7132-1237-5

- M. Brunet de Presle and Alexandre Blanchet, La Grèce depuis la conquête romaine jusqu’à nos jours., Firmin Didot, 1860.

- A. Hugo, France militaire. Histoire des armées françaises de terre et de mer de 1792 à 1837. Delloye, 1838.

- Olga Polychronopoulou, Archéologues sur les pas d’Homère. La naissance de la protohistoire égéenne., Noêsis, Paris, 1999. ISBN 2-911606-41-8

- Arch. de Vaulabelle, Histoire des deux Restaurations, jusqu’à l'avènement de Louis-Philippe, de janvier 1813 à octobre 1830., Perrotin, 1860.